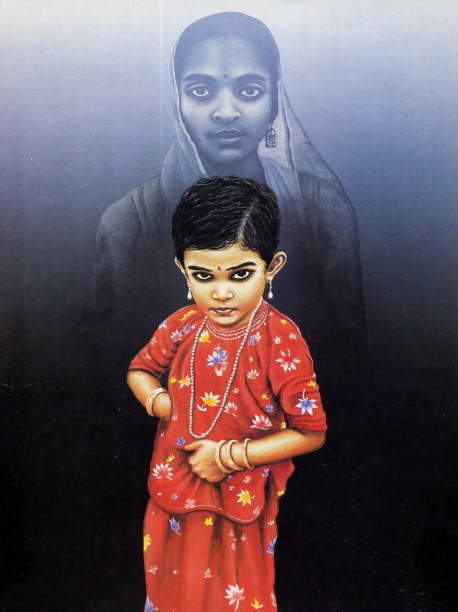

The case history of a little girl from West Bengal suggests she remembered a life she had lived before.

By Jayadvaita Swami

When Sukla Gupta was a year and a half old and barely able to talk, she used to cradle a pillow or a block of wood in her arms and address it as “Minu.” Minu, she said, was her daughter.

And if you believe the story Sukla gradually told over the next three years, Minu actually was her daughter—but in a previous life.

Sukla, the daughter of a railway worker in Kampa, a village in West Bengal, India, was one of those rare children whose testimony and behavior give evidence for the theory that your personality survives the death of your body and travels on to live in another body. This is the theory of reincarnation.

For some five hundred million of the world’s people, reincarnation is more than a theory—it is a fact, a given, a part of their everyday understanding. It’s what they’ve learned from their scriptures, and what generations of their forefathers have believed for thousands of years.

Aside from people in the East, Western philosophers at least as far back as Plato have found it reasonable to believe that our souls have lived before, in other bodies, other lives, and will live again in new ones.

If we have lived other lives, you might ask, why don’t we remember them? But memory is a tricky thing. We’re lucky if we can remember where we’ve put our car keys. So even if past lives are a fact, it’s not surprising we can’t remember them.

But at least a few of us apparently can.

Sukla talked not only about her daughter, Minu, but also about her husband, “the father of Minu” (a good Hindu wife avoids speaking of her husband by name). She also talked about his younger brothers Khetu and Karuna. They all lived, she said, at Rathtala in Bhatpara.

Sukla’s family, the Guptas, knew Bhatpara slightly—it was a city about eleven miles south—but they had never heard of a place called Rathtala, nor of the people Sukla had named. Yet Sukla developed a desire to go there, and she insisted that if her parents didn’t take her she would go alone.

What do you do when your daughter starts speaking that way? Sri K. N. Sen Gupta, Sukla’s father, talked about the matter with some friends. He also mentioned it to one of his railway co-workers, Sri S. C. Pal, an assistant station master. Sri Pal lived near Bhatpara and had two cousins there. Through these cousins he learned that Bhatpara indeed had a district called Rathtala. He also learned of a man there named Khetu. Khetu had had a sister-in-law named Mana who had died several years before, in 1948, leaving behind an infant daughter named Minu.

Sri Sen Gupta decided to investigate further.

The story of Sukla is one of nearly two thousand in the files of Dr. Ian Stevenson, Carlson Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Virginia. Over the past two decades. Dr. Stevenson has gathered reports of people in various parts of the world who showed evidence suggesting that they had remembered past lives. About one thousand three hundred of these cases Dr. Stevenson has investigated personally, including the case of Sukla. [Among Dr. Stevenson’s books are Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation (in which the case of Sukla appears) and the multivolume Cases of the Reincarnation Type. Both are published by the University of Virginia.]

When someone seems to have truthful memories of a former life, Dr. Stevenson interviews him, the people around him, and if possible the people of the life apparently remembered, looking for a more ordinary, normal way to explain things. He looks for fraud. He looks for stories with holes in them and conflicting, unreliable reports. But sometimes, as in the case of Sukla, normal explanations just don’t seem to fit.

After Sri Sen Gupta learned of the family in Rathtala, he decided to yield to Sukla’s desire to go there. With the consent of that family, he arranged for a visit. Sukla said that she could show the way to the house.

So in 1959, when Sukla was a little more than five, Sri Sen Gupta and five other members of his family journeyed with her to Bhatpara. When they arrived, Sukla took the lead. Avoiding various possible wrong turns, she brought them straight to the house of Sri Amritalal Chakravarty, allegedly her father-in-law in her past life.

As the party approached, Sri Chakravarty happened to be out on the street. When Sukla saw him, she looked down shyly, following the usual custom for a young woman in the presence of an older male relative.

But when Sukla went to enter the house she was confused. She didn’t seem to know the right entrance. Her confusion, however, made sense: after the death of Mana, the woman whose life Sukla seemed to remember, the entrance had been moved from the main street to an alley on the side.

And the party soon found that Sukla recognized not only the house but also the people in it, including those she said were her mother-in-law, her brothers-in-law, her husband, and her daughter.

Fraud? When some Hollywood movie actress claims to remember a past life as the Queen of Persia, that’s likely the right explanation. But here we’re dealing with a little village girl. She starts talking about a past life as soon as she’s old enough to speak. She knows all sorts of things about people neither she nor her family has ever met. Careful investigators find no evidence of fraud and no normal way the girl could have learned what she knows. And her behavior actually fits the story of her previous life.

Inside Amritalal Chakravarty’s house, Sukla found herself in a room with some twenty or thirty people. But when she was asked, “Can you point out your husband?” she correctly indicated Sri Hari-dhana Chakravarty. Following the proper Hindu etiquette, she identified him as “Minu’s father.”

Sukla and Haridhana Chakravarty were to meet again several times, and Sukla always longed for these meetings. When he was to visit her house, Sukla told her family to make him a meal with prawns and buli. She said that this was his favorite food. Her family did what she said and later found that she had chosen correctly.

Sukla behaved toward Haridhana Chakravarty like a perfect Hindu wife. After he ate his meal, she would eat whatever food was left on his plate, as a devoted Hindu wife would do. But she never ate food from the plate of anyone else.

To try to account normally for this kind of behavior, another explanation sometimes put forward is what is technically known as cryptomnesia, “hidden memory.”

Psychologists know that our minds record more than we consciously remember. Under hypnosis, an old man may vividly describe his fifth birthday party, an event for which his normal consciousness has lost all the details. Or he may recall exactly what he read in a long-forgotten book some thirty years before.

So the hypothesis of cryptomnesia supposes that what appear to be memories of a past life are merely memories of something one has heard or read and consciously forgotten.

This may in fact be the best explanation for many of the “past-life regressions” now becoming popular in journeys through hypnosis. Asked by a hypnotist to go back to a past life, a subject obediently searches his forgotten memories and uses them to dramatize an entirely fictitious “former existence.”

In one notable case, back in 1906, a clergyman’s daughter under hypnosis told vividly of a past life in the court of King Richard II. She poured out a wealth of details, nearly all of which proved to be true, even though many of them were so obscure that they sent researchers hunting through scholarly English histories the girl was most unlikely to have read. Finally, however, it came out that all these detailed facts appeared in a novel. Countess Maud, that the girl had read when twelve years old and had entirely forgotten.

But the case of Sukla, remember, is that of a girl less than five years old. And her recollections of a past life took place not under hypnosis but as part of her usual waking consciousness.

We may suppose that she gathered these memories normally, but this is only a supposition—there’s no evidence of any normal channel through which these memories could have come.

Moreover, Sukla didn’t just recall information—she actually recognized people, people who in this life were complete strangers.

She recognized Mana’s mother-in-law from a group of thirty people. She pointed out Mana’s brother-in-law Kshetranath, and she knew his nickname, “Khetu.” She also recognized another brother-in-law, whose nickname was “Kuti.” But she identified him correctly by his given name, Karuna, which even his neighbors didn’t know.

She also said that her first child, a son, had died while still an infant. This was true for the life of Mana. And Sukla tearfully recognized Mana’s daughter, Minu, and showered her with affection.

If there isn’t a normal way to explain this, maybe there is some other less-than-normal explanation. Perhaps Sukla learned about Mana and her family through extrasensory perception.

Research has clearly shown that there is such a thing as ESP. In rigidly controlled experiments, the late Dr. J. B. Rhine and other parapsychologists have shown persuasive evidence for telepathy (the ability to read another person’s thoughts) and clairvoyance (the ability to perceive objects and events without using your senses). And experiments have shown that both telepathy and clairvoyance can work over long distances.

But although ESP may seem hard to believe, to use it to explain a case like Sukla’s you’d have to believe in super-ESP. Not only would this five-year-old girl have to have incredible psychic powers, but she would have to use them to zero in on a specific family in an unfamiliar city and learn intimate details of their lives. She’d also have to be selective about what her psychic radar picked out, so that she’d “remember,” for example, the location of her father-in-law’s house but be unaware that the entrance had changed, since that took place after Mana’s death.

And then, for purposes yet unknown, Sukla would have to mold what she’d learned into a drama in which she immersed herself in the role of the departed Mana.

Most dramatic in Sukla’s case were her strong maternal emotions towards Minu. From babyhood Sukla had played at cradling Minu in her arms, and after she learned to talk she spoke of her longing to be with Minu. Sukla’s meeting with Minu had all the appearances of a tearful reunion between mother and daughter.

Once Mana’s cousin tested Sukla by falsely telling her that Minu, away in Rathtala, was ill with a high fever. Sukla began to weep, and it took a long time for her family to reassure her that Minu was actually well.

Minu was twelve and Sukla only five. And Minu had grown taller, so Sukla said, “I am small.” “But within this limitation,” Dr. Stevenson says, “Sukla exactly acted the role of a mother towards a beloved daughter.”

And after taking other possibilities into account, Dr. Stevenson cautiously submits that perhaps we can understand this case most suitably by accepting that Sukla was Minu’s mother, just as she thought herself to be.

This brings us back to the idea of reincarnation. Of course, science can never “prove” that reincarnation is a fact. For that matter, science can never actually “prove” anything. Through science, all we can do is gather data as carefully as possible and then try to explain them in the most consistent and reasonable way. And when the body of data grows, our explanations have to grow with it.

Because of the work of Dr. Stevenson and other researchers, we now find ourselves facing a considerable body of data suggesting that reincarnation is a fact.

Yet science doesn’t go far in making clear to us what that fact is.

How does it work? Why does it happen? Who or what is reincarnated? How long do you have to wait between births? Does it happen to all of us, or only a few?

Perhaps one day scientific investigation will come up with answers to these questions. For now, investigators can do little more than gather data and speculate.

So if reincarnation happens to everyone, you can figure on going through it yourself—perhaps countless times—before science even begins to figure out what’s going on.

The members of the Hare Krsna movement, however, have a different way of getting understanding.

Faced with an unfamiliar but complex machine, you can observe it and try to figure out how it works. You can monkey with the thing and see what happens. You can call in friends and get their ideas of what the pulleys, gears, and wires are supposed to do. And maybe you’ll figure it out. Maybe.

But the sure way to understand the machine is to learn about it from the person who built it.

So the direct way to understand the machinery of the universe—including the subtle machinery of reincarnation—is to learn about it from the person behind it.

That there’s a person behind this machine comes near to being self-evident. It’s axiomatic. Of course, you’re free to reject the axiom. But then you’re faced with the task of explaining how things “just happen” to work, how everything in the universe “just happens” to fit together, without any intelligence behind it.

You can say that everything happens “by chance” (which is no explanation at all). You can ascribe everything to some ultimate impersonal force that, without intelligence or volition, gets everything to work. Or you can sidestep the problem by saying that everything we see is merely an illusion: “The machine doesn’t even exist.” But then you have to explain where the illusion comes from. And that puts you right back where you started.

It’s easier and more reasonable, therefore, to assume that behind the workings of the cosmic machine is the supreme intelligence, or the Supreme Person. This is the entity to whom we refer when we use the name Krsna.

For various excellent reasons (explained elsewhere in the issues of this magazine), we accept that the book known as Bhagavad-gita conveys the words of Krsna Himself. So the members of the Hare Krsna movement, like devotees of Krsna for thousands of years, learn about reincarnation from the words of Bhagavad-gita

In Bhagavad-gita Krsna tells us that reincarnation happens to everyone. “For one who is born,” Krsna says, “death is certain. And after death one is sure to be born again.”

Krsna compares this journey through a succession of lives to the changing of clothing. Your true self—your “soul”—is eternal, but it goes through temporary bodies, one after another.

So it’s not that you “become a different person” when you change from one body to the next, any more than you become somebody else when you change your clothes or when you grow from a child to an adult. You’re always the same you, but you watch your body and mind transform from those of a child to those of a youth and then those of an old man or woman. Similarly, Krsna says, death is but a transformation from one body to the next.

Still, death is like nothing else under the sun. It’s the biggest jolt there is. And when we get to the other side, we forget all about what we were doing in the life before, just as a person who falls asleep forgets what he was doing during the day and then wakes up and forgets about his dreams.

In rare cases, though, memories may persist, as they apparently did with Sukla Gupta. Sukla remembered her home, her family, and her clothing from the previous life. She talked about the three saris she used to wear, especially the two made of fine Benares silk. And when she visited what she said was her former home, she found the saris stored in a trunk, jumbled in with clothing that belonged to others. She picked out the three saris she said were hers, and in fact they had been Mana’s.

Sukla talked about a brass pitcher in a particular room of the house. When she visited, the pitcher was still there. The room had been Mana’s bedroom, and Sukla correctly showed where Mana’s cot had previously been. And tears came to Sukla’s eyes when she saw her old sewing machine, the one that Mana had previously used.

But even if we forget our previous lives, they influence our present one nonetheless. The Bhagavad-gita says that it’s what we’ve done and thought in our past lives that determines what kind of body we start out with in this one. And by what we do in this life, we’re paving our way to the next.

According to the Bhagavad-gita, we’ve already been through many millions of lifetimes, and it’s possible we’ll have to go through many millions more. Some of them may be in human bodies and some in the bodies of lower forms like animals and trees.

But by spiritual realization, the Gita says, we can free ourselves from spinning through this endless cycle of incarnations. We can transcend material existence altogether and return to our eternal home, in the spiritual world with Krsna.

The Gita points out that each of us is eternal and Krsna is also eternal. And our real existence is our eternal life with Krsna.

As we travel from lifetime to lifetime, we can’t hold on to anything, for everything in the material world is temporary. Everything material fades away and ultimately loses meaning.

The Bhagavad-gita therefore advises that now, in this present human life, we should fully use our energy and time for spiritual realization.

By the time Sukla was seven, her memories of her former life had begun to fade. Yet even before the memories left her, that life was already gone. Sukla had mentioned that in her former life, as Mana, she’d had two cows and a parrot. But after Mana’s death the cows had died, and the parrot had flown away.

Leave a Reply