Transcendental Commentary on the Issues of the Day

Watt’s So Funny?

by Drutakarma dasa

Secretary of the Interior James Watt was forced to resign because of some unfortunate remarks he made about his appointees to a national coal commission. His panel had, he said, “every kind of mix you can have. I have a black, I have a woman, two Jews, and a cripple.”

Secretary of the Interior James Watt was forced to resign because of some unfortunate remarks he made about his appointees to a national coal commission. His panel had, he said, “every kind of mix you can have. I have a black, I have a woman, two Jews, and a cripple.”

The almost universal outrage at this statement suggests that people expect the nation’s leaders to display a vision of equality that goes beyond the obvious disparities of physical form and appearance. So there arises a nagging question—what kind of equality are we then talking about? After all, the woman on the panel isn’t a man, the black person isn’t white, the Jews aren’t Moslems, and the physically disabled person is, in fact, in some way crippled. If there is equality, we have to look further. It’s doubtful that many of the people who got upset at Mr. Watt’s remarks have analyzed this very deeply. But their response does point to an instinctive awareness that the equality of human beings transcends material conceptions, that it is ultimately a spiritual equality.

In other words, we expect our kings to be philosophers. In ancient India’s civilization this ideal was actually attained, and a ruler would be known as a rajarsi (saintly king). The rajarsis received a kind of training for political leadership that has not been talked about very much in the West since the days of Plato, who wanted philosopher-kings to rule his republic.

In the Bhagavad-gita it is said, panditah sama-darsinah: a wise man sees all living beings with equal vision. But this outlook was not meant just for solitary mystics. The Gita’s knowledge was specifically intended for those who governed society.

According to the Vedas, the equality of all living beings lies in their common origin in the Absolute Truth, the Supreme Personality of Godhead, Lord Krsna. In the Bhagavad-gita Lord Krsna states that all living beings are equally His spiritual parts. As the authors of the Declaration of Independence correctly stated five thousand years later, “All men are created equal.” Properly understood, this statement refers to the soul, not the body.

Without the presence of the soul, the body is simply a lifeless combination of material elements. The Bhagavad-gita compares the soul to the driver of a machine. So we may see that one man is riding a bicycle and another is driving a car. The first may be going twenty miles per hour and the other, ninety miles per hour. Still another man may be flying a jet airplane. Essentially the drivers are equal, but because of their vehicles they manifest different powers and abilities. Similarly, the soul may be present in a body that is male or female, black or white, Christian or Jewish, crippled or uncrippled. But although the bodies may be different, the souls within are the same.

A government administrator must understand this and help others to understand this, because only this knowledge will free people from suffering. Every material body must grow old, get sick, and die. And then, according to the law of karma, the soul must enter another material body and repeat the process. Understanding this, a leader will be able to act for the citizens’ real welfare. Ultimately, this means educating the people in the techniques of self-realization, so that they can be freed from the cycle of birth and death.

A leader lacking this higher knowledge will be unable to see with equal vision. He will make all kinds of distinctions based upon the physical body. And rather than helping the citizens, he will tend to misuse his powerful position to exploit them. Ultimately, the reason so many people were upset about Watt’s remarks, was that they revealed, however indirectly, his potential to act in a way injurious to those under his care. And that’s not a laughing matter, as Mr. Watt himself found out; it’s a disqualification for holding public office. But the big question is, How many more of our public officials have attitudes and perceptions similar to Watt but are more expert in concealing them?

Our National Defense: Up In Smoke?

by Satyaraja dasa

On May 26, 1981, an EA-6B electronic warfare plane crashed on the flight deck of the nuclear carrier Nimitz Medical tests showed that six of the fourteen men killed in the accident had regularly used marijuana and that three were probably high when they died. In a letter to the Los Angeles Times, one Nimitz crew-member wrote: “Sure, a lot of people on this boat smoke grass. So do I. But look around you, friend, look around. Who the hell don’t?”

Drug abuse in the armed forces is perhaps the most alarming offshoot of America’s leading business—the $60-billion-a-year, illegal-drug industry. A 1973 investigation showed that ten percent of U.S. troops on the front lines in West Germany were using heroin monthly, or more often. And a Department of Defense study this year reveals that fifty percent of the enlisted men surveyed use drugs or alcohol on duty.

Widespread drug abuse—in the armed forces and elsewhere—indicates that the average citizen’s day-to-day life is devoid of satisfaction. This lack of satisfaction, the Bhagavad-gita says, stems from our ignorance of the soul’s eternal relationship with the Supreme Person, Krsna. Krsna is the reservoir of all pleasure, and a good dose of Krsna consciousness would put America’s biggest industry out of business.

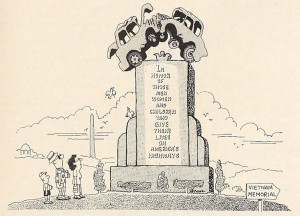

The Auto Industry:

Going Nowhere Fast

by Mathuresa dasa

The 170 million motor vehicles registered in the United States pump 80 million tons of carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide, and hydrocarbons into the air annually. Auto exhaust accounts for most of the smog that hangs over U.S. cities, and that smog is a major cause of emphysema, bronchitis, lung cancer, cardiovascular disorders, and asthma. By rough calculation, breathing the air in New York City is as likely to cause lung cancer as smoking two packs of cigarettes a day.

The 170 million motor vehicles registered in the United States pump 80 million tons of carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide, and hydrocarbons into the air annually. Auto exhaust accounts for most of the smog that hangs over U.S. cities, and that smog is a major cause of emphysema, bronchitis, lung cancer, cardiovascular disorders, and asthma. By rough calculation, breathing the air in New York City is as likely to cause lung cancer as smoking two packs of cigarettes a day.

Eighty years ago, when the automotive industry was just getting under way, no one foresaw that motor vehicles would cause so much pollution. On the contrary, early enthusiasts hailed the auto as a remedy for pollution and other urban maladies. At the turn of the century, horse-drawn carts and carriages with steel-rimmed wheels clattered along the cobblestone streets, creating a sometimes intolerable din. Horse manure littered city streets, and the resulting fumes irritated nasal passages and lungs. Dried horse dung gave rise to a kind of dust that medical authorities blamed for the dysentery and diarrhea plaguing city children. Tetanus was thought to be introduced into the cities in horse fodder, and thirty communicable diseases, including typhoid, were linked to horses and horse excreta.

Automobiles, many argued, would eliminate the horses, horse manure, smelly and unsightly stables, as well as the cobblestone streets that provided the necessary footing and traction for horses. As a Scientific American article explained in 1899: “The improvement in city conditions by the general adoption of the motorcar can hardly be overestimated. Streets clean, dustless and odorless, with light rubber tired vehicles moving noiselessly over their smoothe expanse, would eliminate a greater part of the nervousness, distraction, and strain of modern metropolitan life.”

Not only would automobiles reduce urban stress, but they would create an alternative to urban living. The auto would enable workers to spend the day at their factories and offices in the city and live in the countryside miles away. “Imagine a healthier race of workingmen,” the Dearborn Independent exhorted its readers in 1904, “who, in the late afternoon, glide away in their own comfortable vehicles to their little farms or houses in the country. . . . ” As Henry Ford put it, “We shall solve the city problem by leaving the city.”

The growth of the auto industry did spark a suburban real estate boom, as well as rapid growth in the steel, rubber, plate glass, and other related industries. Between 1910 and 1927, 15 million Model T’s rolled off the Ford Motor Company’s assembly lines, and the nation laid down hundreds of thousands of miles of paved streets and highways. Both directly and indirectly, the automotive industry contributed greatly to the prosperity of the twenties.

From the start, however, the disadvantages of motor transport were apparent. By the early 1920s, auto traffic in American cities was one of the major problems of the day. And in 1924 alone, 23,600 people, including 10,000 children, died in auto accidents. The number of deaths rose each year—to 40,000 by 1940 and to 50,000 by 1965. Since 1965, despite the enforcement of Federal auto safety standards, the figure has remained around 50,000 a year. All told, more Americans have died in motor vehicle accidents than in all the wars America has fought.

In terms of the economy as well, the benefits of the auto industry are questionable. Auto production contributed significantly to the wealth of the Roaring Twenties, but when the market became glutted around 1926, production fell off. This, of course, affected the national economy, and some economists point to the leveling of the auto market in the late twenties as a major factor in the stock market crash of 1929.

Today motor transportation is so intricately woven into the fabric of our life that it’s hard to imagine doing without it. The auto not only allows us to live miles from our places of work, our schools, our shopping centers, and our recreational facilities—it forces us to. People can no longer spend their days near home and family. The automotive industry has disrupted and divided our lives and made us dependent on our expensive, dangerous, smog-belching vehicles. We spend an enormous amount of time and money to purchase and maintain our cars, and they, in turn, exert an enormous influence on our lives. So the question might be raised: “Who’s driving whom?”

And yet, dependent as we are on our automobiles, we may have to do without them, at least to some extent. Motor vehicles in the United States guzzled almost 115 billion gallons of gasoline in 1980, and many authorities fear that at that rate, the supply can’t last long.

But would the loss of the automobile be a blow to progress, or would it be a blessing? The Srimad-Bhagavatam points out that although what we so often refer to as progress—developing a “higher standard of living”—may raise some standards, it lowers others. And the bad effects of such “progress” cancel the good effects. The higher speed of automobiles over horse-drawn vehicles, for example, has brought with it a disproportionate lowering of safety and health standards.

Progress toward material happiness, the Srimad-Bhagavatam states, is always illusory. Endeavors for such progress “result only in a loss of time and energy, with no actual profit.” (Bhag. 7.6.4) And that’s no exaggeration. Try subtracting the millions killed and maimed in auto accidents from the billions of dollars the auto industry has added to the gross national product. At best, you get zero.

Not only is material advancement unprofitable, but “the results one obtains are inevitably the opposite of those one desires.” (Bhag. 7.7.41) For example, such a formidable health menace as air pollution from auto exhaust is the result of attempts to improve public health and the urban environment. And if we think we can escape from auto exhaust by adopting, say, electric cars, or solar cars, we will find other disadvantages to contend with. That’s the nature of material progress.

In addition to being self-defeating, material progress diverts our attention from spiritual progress. The Vedas recommend, therefore, that instead of wasting time pursuing illusory material progress, people should live simply and peacefully, devoting their time, energy, and creative intelligence to the service of the Supreme Person, Krsna, and thus free themselves from the cycle of birth and death. Until we are free from the miseries of repeated birth and death, there is no question of a higher standard of living.

A devotee of Krsna will admit that, as things stand now, the automobile is a practical necessity, and he’ll use the automobile to take Krsna consciousness to every city and town. But he doesn’t mistakenly see the auto as a symbol of progress. He sees that when you tally up all the automotive industry’s balance sheets, you find an extremely poor business record: eighty years of hard work—and no profit.

Leave a Reply