A former civil rights worker

went to the war-torn island with

an ancient peace formula.

It was disarmingly simple.

by Gurudasa Swami

“Civil War in Northern Ireland.” “Bomb Scare in Hotel Europa—Three Die in Terrorist Attack.” The headlines screamed across the world from the tiny island.

“Control Zone—Unattended Vehicles Will Be Towed Away,” the yellow signs shouted, and they seemed to be everywhere. At first we couldn’t figure out the reason for the signs, but we soon learned: terrorists put a bomb in a stolen car, drive the car-bomb up to a target, then run and let the bomb go off. Usually, the target is a pub; more casualties that way. We also saw plenty of oil drums filled with cement and connected by thick iron bars, looking like so many fat folk dancers with their arms on one another’s shoulders. These drums keep car-bombs from coming up past the curbs and next to the buildings.

A man with one leg, another with a patch over an eye, a maimed child—all were common sights. At the infamous junction of the Falls and Shankhill roads (the scene of much of Belfast’s violence), we met a man from the bomb squad, which is called “Felix” because they need nine lives and then some. Whenever there’s a bomb scare or an unattended package or car, they come to investigate and, if necessary, to deactivate. “Our job isn’t easy,” the man explained, “because these bombs have devices that explode if you move them or even shine a flashlight on them. Quite a few of my friends have been blown up.”

One day we saw and heard two great explosions and two buildings blown to the ground. Rubble was everywhere. A blackish cloud hung over the area for hours, and human limbs stuck out from between the wood and stone. Another day we were on the way to a launderette with large bundles of clothes. We asked directions, and when we reached the spot where the launderette was supposed to be, there was nothing left. Most times when we went to use a phone box, we’d find it bomb-gutted.

By asking a few questions, we learned that the terrorists start their training at age five and their vandalism at age six. In fact, a six-year-old’s first duty is setting bombs off. As a result, bands of youngsters roam the streets, and bombs may explode at any moment. One day we noticed that except for a few smouldering scraps, a huge gasoline storage tank had disappeared.

On every street we saw the remnants of houses that may once have been the whole world to the people who lived in them. The illusion was gone now, of course. Here was bare-faced evidence of how the material world changes and decays. You just couldn’t get around it—something once quite solid now destroyed, someone once quite alive now dead, someone once quite happy now heartbroken. You could say this for Belfast: the old adage “Here today, gone tomorrow” really hit home.

The people’s character seemed just about as changeable—a strange mixture of piety and mischief, peace and violence, happiness and sadness, mysticism and cynicism, friendliness and suspicion. Very rarely did anyone walk alone; they were more likely to stay in groups, almost like herds of animals leery of attack. Younger children told me that they didn’t go out after dark, for fear of being shot. Anxiety appeared to be the watchword.

One man who visited our mobile bus-temple said it seemed like “a portable oasis.” It was a small oasis, to be sure, but anyone could come in off the street and take in the peaceful feeling of the little temple room and its library of age-old Vedic literatures, English renderings by my spiritual master, His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada.

Our advance man, Bhaumadeva dasa, would go ahead of the bus to see professors, community leaders, terrorist leaders, police spokesmen, youth groups, and newspaper and t.v. reporters, and he set up a good number of festival programs for our group. A number of people were so glad we were coming that they gave us an honorarium. In a town called either Derry or Londonderry (depending on your point of view), one man was crying. “We thank you so much!” he said. “No one comes here anymore—they’re too afraid. They won’t even come for money, what to speak of for an idea or belief, as you people have.”

In Belfast we saw hundreds of bombed-out houses, with windows broken and roofs charred—blackish skeletons that used to be brownstone shelters. Soldiers carrying machine guns were a common sight. But life went on, the soldiers mixing with the shoppers, even though at any moment violence could break out. The people stepped over and through rubble as if it didn’t exist.

On the day we arrived, television, radio, and newspaper interviewers came to talk with us. One man asked, “What can you suggest that would put an end to the fighting between the Catholics and the Protestants?”

“We can overcome this sectarianism,” I said, “if we can understand what’s inside our bodies—if we can relate on a loving basis of soul to soul. This fighting because of ‘Catholicism’ or ‘Protestantism’ or any ‘ism’ is artificial. Love of God is for everybody; it’s not ‘Catholic’ or Protestant.’ Would we say, ‘He’s Mr. Green Coat; he’s Mr. Orange Shirt’? Then why should we say ‘He’s Catholic; he’s Protestant’? What is the historical or geographical beginning of love of God? It has no beginning or end. So the alternative to this problem of sectarianism is to understand that we are not these material bodies, with all their labels. We’re spiritual persons; we all have the same spiritual father.”

In a slightly challenging tone, a t.v. announcer asked, “Do you think that Northern Ireland can use another religion? Do you think another religion will help?”

I answered, “This is not exactly a religion; it’s a way of life. Northern Ireland and the world could surely use another way of life.” The man ended his interview with “Thank you” and a thoughtful “Hmmm.”

Many people would approach us as we went around the country. Sometimes they’d say, “If there were more like you, this would be a better place.” Apparently they wanted to hear us, because they made room for us right in the middle of their towns. So, surrounded by soldiers, barricades, and barbed wire, we put on festivals. The first day in Lurgen a huge crowd of people came.

Of course, at night we always made it a point to stay outside the cities, because of the possible violence. In Lurgen, for instance, we stayed near a big lake. In Lisburne, we found a little country lane. In Bangor, a port town, the people gave us permission to stay at Pickie Pool Marina, a natural seawater pool.

We put on festivals in Bangor (on the coast) for three days. Each one of our programs included chanting and explaining the maha-mantra (Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare), a short talk with questions and answers, a drama, a film, and vegetarian prasada (spiritual food). The people were really receptive.

One of the highlights, we found, was the drama. We put on two street plays, The Boatman and the Scholar and The Genie in the Bottle. The latter depicted a genie who came out of the bottle warning that if he didn’t get something to do, he’d kill the person who’d set him free. The idea was that if you don’t engage your mind in something useful, your mind will do away with its master, your intelligence. Bhaumadeva, our advance man, made a delightful genie—with green cheeks, purple lips, wide, bulging eyes, and so on. He’d spring out of the “bottle” (a blanket) right there on the street. In the towns and villages we did this play many times, and the people would get amazingly involved.

At first the king (who had liberated the genie) would say, “I want you to repair and wash all the broken windows in Belfast.” That’s a lot of broken windows, but the genie would make a noise, run off, and be back practically in no time.

“It’s done, master.”

Next the king would ask the genie, “Trim all the hedges in my kingdom,” and the genie would run off and come back again almost before the king could turn around.

Finally, with sword flashing, the genie would say, “Give me something else to do—or I’ll kill you!”

When the king couldn’t think of anything else to keep the genie busy, he’d muse to himself, “Ah! The genie should chant Hare Krishna—that’s one thing you can do forever!”

At that point, the king encouraged the whole crowd to help the genie in chanting, and the people would join in the chanting to help keep the genie satisfied. A young girl said, “This is the third time I’ve seen this play; I like the genie.”

Many times we’d talk with people on the street—all kinds of people, some from the Ulster Defense Army (the U.D.A.), others from the I.R.A., still others from the peace movement, and occasionally a few from “Felix,” the bomb squad.

In Belfast, almost daily we went into the City Centre and through the barricades of the Control Zone, where we put on a street drama, gave an address, and chanted Hare Krishna. The people received us quite well. Once, when a drunken man tried to disrupt the play, the audience shouted him away.

Even the radio and television spread the word when we were getting ready to go into the two big trouble areas, the Shankhill and Falls roads. One was a Protestant stronghold, the other a Catholic stronghold; fighting would break out at the junction. And these people weren’t just squabbling or name-calling. They meant business and shot to kill, and, as I say, their children were taking after them. Yet many from both sides would ask us “When are you coming? When you do, our house is the green one on the right” (or whatever). Once the car battery ran out, and I asked a gentleman to help. He did, and he asked me what we were doing in Northern Ireland. When I told him he said, “If there’s anything you need—anything—just come to my house and ask me. Day or night-just ask.”

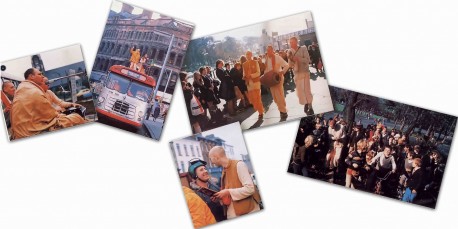

On top of the bus we mounted a platform that held six to eight devotees. Then we installed a run-around railing and a public-address system, complete with two microphones and some sturdy speakers. All over Northern Ireland’s towns and villages, most people were both friendly and eager to share our festive mood. Sometimes they’d dance in the street or give us “thumbs up” from their windows. Policemen and soldiers grinned. One trooper put his gun down and took a photo as we passed. The children ran out of holes in the battered walls. Old people smiled and hobbled along after us, and many swayed their heads to one side (their silent way of saying, “That’s nice”). Some of the kids jumped up and down when we went by, and many of them climbed onto the bus and joined us. Others just waved, and we waved back. Once, through open windows, what looked like a whole schoolhouseful of hands and faces waved and smiled.

People encouraged us in so many ways. They were especially friendly when we rode on the top of the bus like that. In a grand procession we’d go along the Falls Road, chanting and dancing on top of the bus. At the same time I’d announce that we were going to come to a specific park the next day and give out spiritual food. Then Bhaumadeva—the genie—would get out of the bus and pass out leaflets and candy. A million kids would follow him, as though he were handing out gold. They were chanting Hare Krishna and skipping and following the bus down the street.

Also, I’d talk to the people through the public-address system and encourage them to chant. Sometimes, when I saw people standing before their shops, I’d say something like, “Everyone in Nelly’s Knitting Store should chant Hare Krishna.” They would be all excited because we were speaking about them in their shops, and they’d try to chant. Other times I’d say, “Anyone with his hands in his pockets and his front teeth missing should chant Hare Krishna.” When they realized that we were speaking about them, they’d perk up and chant. Or I’d say, “Anyone walking a dog should chant Hare Krishna,” or “All patients in the Royal Hospital should chant Hare Krishna,” and so on.

One very interesting thing happened in the Falls Road. Just when we were preparing to leave and had stopped chanting, some of the same children who’d been so joyous and peaceful reverted to their old ways. They started picking up stones and throwing them at us on top of the bus, and we had to leave rather hurriedly. It seemed that as soon as the chanting stopped, the genie of the mind wanted to go on a killing spree again and block out the natural good feelings for Krishna and everybody else.

It was becoming clear. When someone is thinking “I’m Irish,” “I’m American,” “I’m African,” that’s a lower state of consciousness. A more evolved state of consciousness would be, “I’m a spiritual individual; I have a lasting, loving relationship with the Lord, with everyone.” Of course, that basic idea appears in all the scriptures of the world. You’d think it would have sunk in by now, but some of these people weren’t too keen on hearing it. Sometimes they’d come up, pretend to be interested, and suddenly start jeering. And sometimes young people would throw stones. Usually, though, the people were beautiful.

Take the Senior Citizens Club of Coleraine, for instance. The festival we put on for them was much like other festivals (including ones at the Overseas Students Club, the Baha’i hall, a girl’s school called Fort Hill Intermediate, Ulster College, Queens College, and Londonderry Technical School).

“We’re members of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness,” I began. “This isn’t a new movement. It’s been going on for thousands and thousands of years. In fact, the Vedic culture is as old as the planet. We’re dedicated to simple living, with God as the goal and God as the center of all that we do. This life-style is also known as bhakti-yoga, the yoga of devotion.

“The backbone of this yoga process is chanting or singing the holy name of the Lord. This chanting is called a mantra. The word manas means ‘mind,’ and tr means ‘to deliver’—a cleansing of the mind. When we sing Hare Krishna, we cleanse the mind of all the dust that has accumulated there. This is a yoga process that we can all do very simply. Yoga doesn’t really mean that you have to do gymnastics or push your nose; it means that you link up with God, Krishna.” Then I said the Hare Krishna mantra, and the people said it after me.

“Now I’d like to introduce these ancient instruments. These little hand cymbals are called karatalas; they’re made from old guns—certainly a nice alternative for Northern Ireland. This is the basic rhythm—one-two-three, one-two-three, one-two-three-and you can follow it by clapping your hands. Then I’d introduce the mrdanga (an oblong clay drum whose small end makes a bell-like sound and whose big end makes a long, low sound) and the harmonium (a small, hand-pumped Indian “organ”). While everyone was clapping, I explained that chanting is a spiritual conversation. “First you hear the leader sing, and then you sing while he listens. So let’s try it.” The senior citizens got into the chanting easily and seemed to be really enjoying themselves. You’d have sworn they had done this before.

Then I spoke a little bit about the “old-age problem.” “In the Vedic culture,” I said, “people who were old and experienced in living were honored rather than neglected. Even if an older person couldn’t walk far, people would come to hear him. This is called sannyasa, the renounced stage of life. At that point all the knowledge, all the training, all the experience, all the practice that you’ve gained you give to others. Not that the very people you once supported now reject you—instead, they respect you all the more. Nowadays, they’re only waiting for you to leave them something in your will. In the Vedic culture, the elderly really give something to the whole society—they give God consciousness.”

Before the festival ended we put on our “genie” drama—everyone got involved in it—and again we had a question-and-answer session, feasting, and chanting. During the last chant the senior citizens got up and raised their arms “toward Krishna” (I showed them, naturally), and we did “the swami step” (one foot crossing the other, back and forth—Srila Prabhupada showed this to his first American students, back in 1966). So all of us chanted and danced together. When it was time to leave, these kind people said the festival had been “one of the best moments of our lives. Now, what more can we do for Krishna?”

“If you and your children and grandchildren keep chanting Hare Krishna,” I said, “you’ll see what more Krishna can do for you. For one thing, you’ll have peace here in Northern Ireland.”

Leave a Reply