A Lifetime of Service

Her search was not a sentimental one. She was looking for

a pure spiritual process—a practical way of dedicating herself to God.

by Acarya-devi dasi

I grew up in the sixties, and like most of my friends, I more or less rejected my parents’ philosophy of “getting ahead in life,” although I had always been a good student. By my early teens, I tended to go more inside myself as I questioned, “What is the purpose of life? I’m training up to go and get a job in an office, but what for? There is more to life than this, but what is it? And where do I find it?”

Since childhood I had liked to write poetry and short stories. After school, on weekends, during summer vacation—I spent most of my free time writing, pouring out the innermost thoughts of my heart. I wanted to make a serious career of writing, although I wasn’t thinking of writing as a way to “make a buck.” Rather, it was part of my deep philosophical search, a challenge I had to meet so I could answer questions about the meaning of life. To write, I thought, a person had to be desperate to find answers to the ultimate questions; only in that way could one write prolifically.

I shared my inner feelings with some of my friends who were also using writing as a kind of spiritual quest, and we shared our ideas about the meaning of life. Once, one of my friends, upon being asked what her purpose was in living, replied reflectively, “I am living to try to find something to live for.” It was a deep and desperate expression, one that we all shared: Who am I? Why am I here?

Drugs, of course, were an integral part of our search. By the age of fifteen I had decided I was going to be part of the hip crowd, part of the new generation of self-styled spiritual seekers. (It was 1969, and the flower generation was in full swing.) But after less than a year the novelties of drugs and newfound friends faded. I had seen some of my friends “flip out,” and I was too cautious to proceed with something that might irreparably damage my brain. I began to doubt that I would find happiness in any kind of drug, and by my senior year I had returned to my studies and the pursuit of good grades.

But the spirit of searching for that elusive “something” in life persisted, eventually leading to Europe in 1973. Awed by the many great artists, musicians, and philosophers who had hailed from this continent, I was certain that if I could visit countries with culture, with deep roots in the past, I could certainly trace out some meaning to my life. My father had told me of his early life in Switzerland, and I had been intrigued. I thought that by researching the heritage of my ancestors, by living in their culture and imbibing it, I could perhaps discover my true goal in life.

Europe was filled with thousands of hippies, most of them wandering aimlessly, taking drugs, and having casual sex. Some were spiritual seekers, using drugs under the pretext of attaining “spiritual realizations,” but they didn’t seem to be finding any practical answers to the problems of life—only temporary hallucinatory euphorias. I had come such a long distance, hoping to imbibe some of the foreign cultures, but the people I met were doing the same things I had just left behind. For years afterward, when people asked me what impelled me to go traveling around Europe, I was fond of quipping, “I went there looking for myself—but I wasn’t there.”

By the time I was twenty I had done pretty much everything I had wanted to do, and I thought incessantly about God. Although my family had never been particularly religious (they had stopped going to church when I was a child), because I was distressed about the meaning of life and wanted some direction, I did the instinctive thing: I prayed to God.

In the summer of 1974 a friend invited me to visit a Christian summer camp, and I eagerly welcomed the opportunity. I arrived on Saltspring Island, a fresh, beautiful, but sparsely inhabited island off the coast of British Columbia, with high expectations. I soon noticed, however, that very few of the young people there were interested in spiritual life. In fact, when I arrived, most of them were rushing off toward the beach or hiding in the bushes taking drugs or drinking. They spent little time participating in church activities; the only time everyone gathered together in the church was for meals.

I was disappointed. I had come looking for some new friends who would be interested in discussing God and spiritual life, but all I met were people who were more interested in getting high than in finding God. The minister and his wife were young, pious Christians—good people—but they had obviously failed to turn their congregation toward a religious life.

Yet despite this disappointment, my interest in the spiritual side of things blossomed. At home again, I began reading the Bible, intrigued by the idea of developing a personal relationship with God. The Presbyterian church on the corner was open every morning for two hours of prayer and meditation, and I started regularly attending, praying fervently to God for direction.

At the same time, I also began psychiatric therapy to help me sort out my goals in life. And to relieve my frequent anxiety attacks, I began to use tranquilizers. After nine months of therapy, the doctor’s conclusion—”All you need is a new boyfriend, new friends, and a new job”—catapulted me, disgruntled, out of individual therapy into group therapy.

I also attended the church’s Sunday sermons, but somehow I always felt something was missing. Most of the congregation would sit through the sermon impassively. The Reverend W. often spoke of how Christ had died for our sins. I knew some of the members were not following the codes of God—there were couples who were “living in sin”—but it didn’t appear that they had any intention of trying to reform their bad habits.

Although I was sincerely trying to understand God, these sermons failed to touch my heart. It seemed the minister was advocating an idealistic standard of behavior that no one was following. I thought that we should not only repent for our sins—as he was constantly urging—but also give up those sins once and for all. Hadn’t Jesus, upon forgiving the prostitute for her sins, advised, “Now go and sin no more”?

Frustrated by these sermons, I thought to myself, “No, there’s more than this! I know there’s more than this!” I had almost come to feel foolish for wanting to find happiness and meaning in my life, as if I were struggling to attain something that simply didn’t exist. But if it didn’t exist, I asked myself, why did I want it so badly?

One day Reverend W., having noted my regular attendance at church, called me in to speak with him. In the course of our conversation I asked him what the difference was between his church and other churches—a question that had been puzzling me, since there were sixteen churches within a six-block radius of my apartment. I particularly wondered why some churches allowed intoxication, whereas others did not. What was his policy?

“Well,” replied the Reverend, “when I go home, I can have a drink. But we don’t believe in becoming intoxicated.” But why, I wondered, did he draw a line between having a drink and becoming intoxicated? Wasn’t the aim of drinking to become intoxicated—even if just a little? I was confused, and I feared that venturing out to the other churches to ask my questions would only increase my bewilderment.

I wondered why I was suffering so much. Although out of fear of rejection I had always tried to maintain a facade of happiness, I was losing my motivation to play the game. Then one day I made another discovery: I had become dependent on tranquilizers; I couldn’t start my day without them. After two years of psychotherapy, I had become bored with therapy groups and depressed by drugs.

I began reading books on reincarnation and the occult, thinking this could give me a clue about the secrets of life. James Pike’s The Other Side was an intriguing account of a bishop whose son had died; he felt his son was still communicating with him. I had often wondered what happened after death, and this book piqued my interest. It suggested many fascinating possibilities: Had I lived in other times, other places, doing other things? Would I live again?

In my own way, I was searching for God through my readings. My search, however, wasn’t merely a sentimental one: I was looking for a pure, spiritual process that I could adopt in my everyday life. I recalled how in my childhood, adults had said to me, “Don’t do as I do; do as I say.” But the ideal teacher, I felt, would not only be able to tell me what to do but would also be pure and dedicated to his own teachings. Somehow, I wanted to find that teacher.

In February of 1977 a friend who had just spent a year in Asia came by to see me. In Nepal he had met a yogi who told him, “You should read the Bhagavad-gita.” When my friend returned to Canada, he went to a hip bookstore on Vancouver’s Fourth Avenue, looking for a copy.

“Sorry, we don’t have the Bhagavad-gita here,” he was told, “but try the Hare Krsna temple. They have it there.” As it turned out, the temple was within walking distance. So he went there immediately, inquiring about the Bhagavad-gita. Soon, he told me, he had been introduced to the Krsna consciousness movement (which is based on the ancient teachings of the Gita) and began regularly attending the temple functions. He was convinced that the philosophy of Krsna consciousness taught a practical way of living a pure life totally dedicated to God. In fact, he had become so convinced about Krsna consciousness by being with the devotees that he was about to move into the temple and become a devotee himself.

My first reaction was shock: Hare Krsna?! I recalled how I had first begun seeing the Hare Krsnas on the streets of downtown Vancouver in 1969, a group of saffron-clad men who sang and danced on the streets. They struck me as odd, and I would always cross the street to avoid them. Now, however, I felt I was ready to hear what they had to say.

I paid my first visit to the Vancouver temple a week later. It was a Sunday afternoon, the day when Hare Krsna temples all around the world traditionally hold a “Love Feast.” Persons who want to learn more about Krsna consciousness could come and hear the chanting and the philosophy and then take a multicourse vegetarian feast—all free of charge. I knew that this was something different from the things I had experienced before, and I wanted to learn more about it.

When I found out they had accommodations for guests, I asked if I could stay overnight and attend the early-morning meditation (mangala-arati) and classes on the holy scripture. I was invited to stay in the women’s living quarters. The room I slept in was devoid of all but the barest furnishings and several pictures of Lord Krsna and His associates on the wall. I was immediately impressed with the simplicity of the devotees’ lives. “This is what I’ve been looking for,” I thought. The devotees used whatever was necessary for bodily maintenance but didn’t become bogged down with unnecessary “conveniences.” With their bodily concerns kept at a minimum, they were free to spend nearly all their time serving and glorifying God, or Krsna. “Simple living and high thinking” was one of their mottos.

Over the next few months I began regularly visiting the temple and associating with the devotees, and they began teaching me what Krsna consciousness meant. I soon learned that the basic understanding of the Bhagavad-gita was aham brahmasmi: “I am not this body; I am a spirit soul.”

I knew that the devotees followed four principles—no eating of meat, fish, or eggs; no taking of intoxicants; no illicit sex: and no gambling. These activities are considered sinful because they strongly promote body consciousness and thus keep one ensnared in the cycle of birth and death.

Although I was interested in Krsna consciousness, I doubted that I could follow the four regulative principles. I just couldn’t see myself living the renounced life of a devotee. These habits were so deeply ingrained in me that to purify myself of them seemed impossible.

I confronted the devotees with my misgivings. They assured me that Lord Krsna was present in His holy name and that if I called on the names of the Lord—Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama. Hare Hare—Krsna would hear my pleas, deliver me from the clutches of material existence, and situate me in loving service to Him.

I continued chanting Hare Krsna and reading about the philosophy of Krsna consciousness, both with the devotees and on my own. Slowly I was accepting Krsna consciousness into my life. After each visit to the temple I’d come home, go through all my possessions, and say to myself, “I don’t need this. I don’t need that.” Soon I found myself getting rid of many useless things. And my dependence on tranquilizers was gradually disappearing.

I started feeling lighter in mind and heart, knowing that I was giving up unnecessary habits for the higher goal of love of God. I was shedding my unwanted habits and emerging into freedom, like a butterfly emerges from its cocoon. I became more peaceful. I knew I had found what I was looking for, and everyone could see the change in me. I knew I had to become fully Krsna conscious.

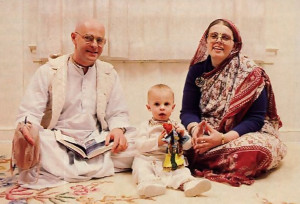

In September of 1977 I first met His Divine Grace Satsvarupa dasa Goswami Gurupada, who was soon to become my spiritual master. His personal example of Krsna consciousness struck me with the most sublime impression: Here was a guru who practiced what he preached. After several months I became his initiated disciple and fully adopted the practices of Krsna consciousness.

At that time, His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the founding spiritual master of the Hare Krsna movement, had recently left this mortal planet. My spiritual master (who was one of his first disciples) was writing his biography, and he needed someone to type it. With my secretarial background and with my strong desire to be connected to a spiritual writing project, I began this work. Although for so many years I had worked at jobs using these skills, not until my spiritual master blessed me with Krsna consciousness and the ability to use my skills in Lord Krsna’s service did I actually become happy.

Now the sixth and final volume of the biography (entitled Srila Prabhupada-lilamrta—“The Nectarean Pastimes of Srila Prabhupada”) has recently been published, and I can continue using my abilities in the service of Lord Krsna. A common misconception is that to become a devotee of God one must give everything up. The only thing that needs to be given up, however, is the mentality of “everything belongs to me.” Rather, everything is done as an offering to the Supreme Lord. Krsna states in the Bhagavad-gita:

yat karosi yad asnasi

yaj juhosi dadasi yat

yat tapasyasi kaunteya

tat kurusva mad-arpanam

“Whatever you do, whatever you eat, whatever you offer or give away, and whatever austerities you perform—do that, O son of Kunti, as an offering to Me.” (Bg. 9.27)

Thus, far from giving anything up, I have rather gained immense benefit: a lifetime of service to Krsna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead.

Leave a Reply