A Revival Of Vedic Arts

From the rustic beauty of terra cotta wall reliefs to the grandeur of temple architecture, India’s ancient culture and art bring us to spiritual self-awareness.

by Visakha-devi dasi

It had seemed like a castle in the sky. For so long I’d been hearing the devotees in the Hare Krsna center in Mayapur, West Bengal, talk about terra cotta panels, terra cotta tiles, terra cotta bas-reliefs, terra cotta statues, terra cotta this, terra cotta that. After seven years I’d developed a kind of apathetic I’ll-believe-it-when-I-see-it attitude.

Once again in Mayapur, on my annual winter pilgrimage, I took an early-morning walk around our grounds to see what had developed while I was away. The air was crisp, and as I approached Srila Prabhupada’s partially completed memorial shrine, I saw kingfishers diving from low branches into the deep green waters of the ornamental lake. I rounded a corner, passed a huge cement statue, and suddenly, to the left of the pathway, caught my first glimpse of a terra cotta panel, splendidly illumined by the rising sun. As I drew closer, my eyes feasted upon the panel’s magnitude, and my mind was transported to centuries past, when, throughout ancient India, entire communities of master artists had worked with intense devotion to decorate temples and shrines.

As I stood there feeling ashamed for having doubted the Mayapur devotees, a sudden voice scattered my thoughts.

“Well, how do you like it?”

I turned around and was surprised to see Surabhi Swami, the minister of architecture for the International Society for Krishna Consciousness and chief architect of Srila Prabhupada’s shrine.

“Well, yes. I mean, it’s fantastic,” I stammered. Surabhi was surrounded by a group of young Western men and women—art students, I later learned, studying the project. Surabhi was explaining the overall artistic concept of the building and of future projects. Thinking it a good opportunity for me to find out more, I joined the group.

“We could have used any number of mediums to decorate the samadhi [shrine],” Surabhi was saying, “but we decided on terra cotta over all others because it’s traditional. We’re presenting a traditional message, so we thought it fitting to use the traditional medium.”

“How old is terra cotta?” someone in the group asked.

“It’s as old as civilization. In the Bankura district they’ve discovered a terra cotta figure from the second century B.C. But that’s nothing. Terra cotta was used during Lord Krsna’s time, thirty centuries B.C., and Lord Rama’s time, millions of years before that!”

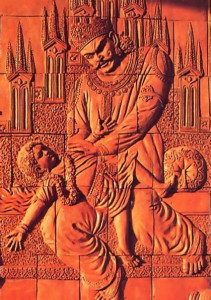

Terra cotta literally means “baked earth”; it’s a hard ceramic clay used in pottery and construction. Now, as I walked through the artists’ work area with Surabhi Swami and the others, I saw it used in fifteen-foot-square, ten-foot-square, and seven-foot-square bas-relief panels depicting pastimes from the Vedic scriptures Srimad-Bhagavatam and Sri Caitanya-caritamrta.

“Dr. George Michell has done a detailed study of the temples and terra cotta of Bengal,” Surabhi Swami said, “and he explains that here in Bengal in the sixteenth century there was a religious revival because of Lord Caitanya and His followers. At that time the upper classes—nobility, landed gentry, intellectuals—were giving their wealth for constructing temples and were spending much of their time hearing about and discussing Lord Caitanya and His teachings. The result was a remarkable development in Bengali religious literature. “The sculptural decorations on Bengal’s many temples paralleled this development in religious literature. The temple sculpture, generally in terra cotta, served as a kind of permanent record of the dramas, songs, poems, and narratives.

“In the second half of the nineteenth century, temple patronage in Bengal declined as the Indian middle class became Westernized and Calcutta became the capital of British India. Artisans found themselves without work and were forced to turn to other crafts, like wood carving. New materials, like concrete and steel, dealt a final blow to the brick and terra cotta tradition. So for us to use terra cotta here is to revive an important art form.”

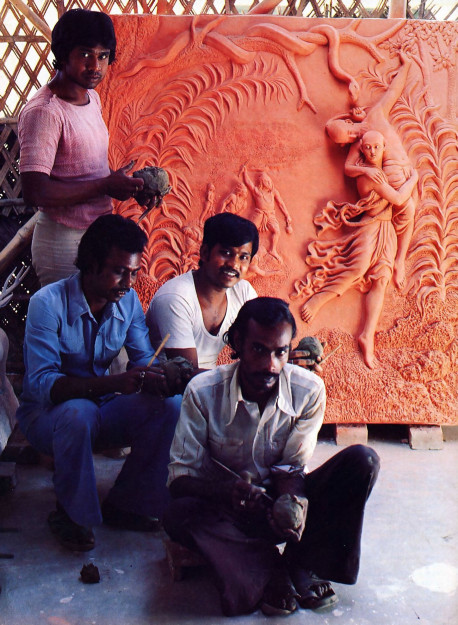

By now we had paused before three shabbily dressed Indians who were working on a relief of Laksmi-devi, the goddess of fortune, being offered presentations by various demigods and goddesses gathered around her throne.

“Not only did we revive the art form,” Surabhi said, “we also reinstituted the integrity of the message. When terra cotta was widely used in temple decorations, the terra cotta artists, like the majority of Bengalis, were illiterate. So they could not become familiar with the Sanskrit scriptures that delineated the pastimes they were depicting. Instead, they took the word of the local Bengali poets and dramatists. The problem was that these authors didn’t hesitate to introduce new episodes and add their own interpretations. So oftentimes the artwork isn’t true to the original.

“But all the art we do,” Surabhi said with a wave of his hand, to indicate the many reliefs in the workshop, “and all that we will do are based on the original pastimes described in Srimad-Bhagavatam and Caitanya-caritamrta. No one here adds any interpretations or new episodes. That’s how we’re maintaining the purity and spiritual potency of this art.”

As Surabhi Swami spoke, I watched the men in front of us work. Judging from their appearance, you might think they were ordinary laborers, yet they were fashioning such a beautiful relief of Laksmi-devi. Immediately, I wanted to find out more about these artists, but being an uninvited newcomer, I kept quiet. Then, as we were about to move on, another woman asked the question I had in mind.

“Where are your artists from?” she said, looking at three men who had stopped their work to observe us.

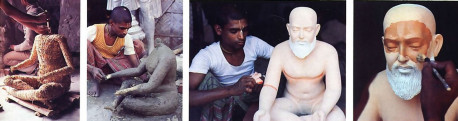

This time, Anakadundubhi dasa, the art director in Mayapur, answered. “We found one family of five talented brothers, and we’ve commissioned them to do this work. This is the eldest and most qualified of them.” He indicated one of the three, a fortyish man in a worn green sweater who had curly, unkempt hair and several days’ growth of beard. “He and two of his brothers do the reliefs from the Srimad-Bhagavatam. The other two brothers work on Caitanya-caritamrta reliefs.

“Srila Prabhupada wanted us to employ local talent,” Anakadundubhi continued, “and this man, the eldest, met Prabhupada here in Mayapur in 1972. Prabhupada told him, ‘You are like my artist disciple. Please work here with us and teach these boys and girls [Prabhupada’s Western disciples].'”

Looking from these men to their work and back again, I impressed upon myself that you can’t tell a man by his looks. For here, hiding behind a common appearance, were three qualified and devotional artists.

It was time for lunch, and as the group dispersed, I walked up to Surabhi Swami. Looking at him, I remembered when I first met him—practically bumped into him—a tall, lanky Dutchman who was strolling around our ISKCON land in Bombay in 1972. He had introduced himself to me as “Hans” and said that his wife and brother were devotees and that he’d been to our temple in Amsterdam. The day after our meeting, he had met Prabhupada, and before long Srila Prabhupada had had him sitting in the room connected to his own, drawing plans for our Bombay temple. That’s where I had seen him for days, sitting at a small round table next to Prabhupada’s door, designing a temple. Eventually he had been initiated. To date he has completed not only the Bombay temple but also the ISKCON Vrndavana temple. (Srila Prabhupada was pleased and declared that as long as these temples stood, Surabhi’s Krsna consciousness would also stand.)

Before I could speak, Surabhi Swami spoke to me, noting how the three artists had immediately gone back to work. “You can tell the artists from the laborers,” he said, “because the artists are absorbed in their work. With the laborers, you have to push them, watch them, and as soon as time’s up, they’re off to their homes. But the artists have pride in their work. They’ll go day and night hardly noticing that the time has passed.”

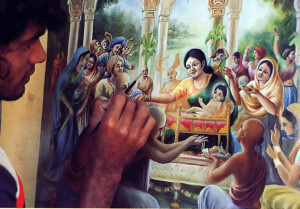

Surabhi spoke more generally about art. He said that spiritual art, more than being decorative, more than being an expression of artists’ feelings or experiences, was a way to meditate on higher beings—ultimately to invoke the presence of the Supreme Personality of Godhead and His incarnations and expansions.

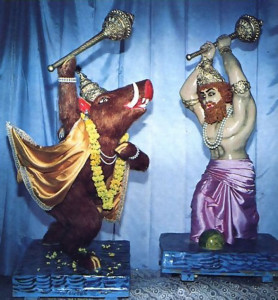

Later I saw a book that Surabhi had referred to: The Hindu Temple, by the world-renowned specialist in ancient Indian art and architecture Stella Kramrisch. She quotes Vedic scriptures, like the Brhat-samhita, which describe in detail specific proportions and features of the incarnations of the Supreme Lord. These texts guide the sculptors, who fashion statues and reliefs that directly convey divinity to the beholder.

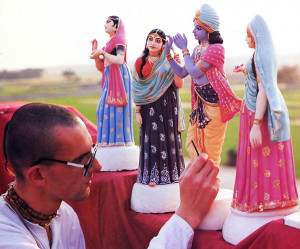

Srila Prabhupada has often explained how God is present everywhere by virtue of His diverse energies. In His Deity forms in the temples, however. He is present personally. Pure devotees not only see Him there, they also have conversations and pastimes with Him. (Several of these are recorded in Caitanya-caritamrta.) Hearing Surabhi Swami speak and having read of the exactitudes in Deity sculpturing, I became awestruck by the potency and contribution of Vedic art in society: the artists, by their art, were ushering their viewers into the divine presence of God.

The next day, when Surabhi Swami invited me to go with the group to a nearby terra cotta temple, I happily accepted. It turned out to be not one temple but three grouped together. The first, built in 1849, was small, single-domed, and covered with intricate and detailed figures in terra cotta, The next two temples were a century older, both with twenty-five domes and less-refined terra cotta work. Surabhi Swami pointed out that the bricks must have been molded while they were still wet, then baked and set in a complex, patterned formation to make the temple walls.

During the jarring two-hour drive back to Mayapur, over innumerable potholes and worn-out roads, we discussed what Vedic art means. “Vedic art,” Surabhi pointed out, “comes from the Vedic culture, which flourished in India five thousand years ago, when society had four social divisions [intellectuals, administrators, merchants and farmers, and laborers] and four spiritual divisions [celibate students, householders, retired men, and renounced monks]. These are natural divisions, just as my head, arms, stomach, and legs are natural divisions of my body. As the parts of the body work harmoniously, so the Vedic society was known for its harmony. Everyone worked according to his propensity and was able to fully develop his individuality while progressing toward life’s highest goal—love of God.

“Vedic art reflected this highly evolved culture. The ultimate goal of this art was to please the Supreme Lord, Krsna. And the artists accomplished that by attracting people to Krsna, by heightening people’s awareness of God.

“But over the centuries, Vedic culture and art declined, until Lord Caitanya’s renaissance, which resulted in temples springing up in all parts of India, like the ones we saw today. After Lord Caitanya, the Vedic culture declined once more. Now, inspired and directed by Srila Prabhupada, we’re offering it again in the form of Krsna conscious culture and art—writing, photography, architecture, sculpture, painting, cinema, music—all meant to bring us to spiritual self-awareness.”

I suddenly realized why going to a Krsna temple in India was so different from going to one in the West. In both cases, the Deities are installed and are the center of the temple and the reason for it. And in both cases the temple vibrates with the sounds of the holy names of the Lord. And in both cases the Lord is worshiped with flowers, incense, ghee lamps, art, drama, ceremonies, and discourses. But in the West, most temples are converted houses or apartments, while in India the temples are designed and built specifically as temples, and the potency of Vedic art is enshrined within them. Often the temple dome will be visible for miles around, and just by seeing it one remembers the Lord. While seeing a temple, we view sacred architecture. While walking through a temple’s halls, we are enclosed in a dim, soothing atmosphere caressing the mind and eye after the fierce daylight and hectic pace outside.

The temple atmosphere derives greatly from the architecture and carvings, which create a harmony of height, breadth, and depth measured by rhythms of graded light and darkness. At first, more than recognizing the identity of the pastimes in relief on the walls, ceiling, and capitals, and more than admiring the perfection of the workmanship, one communes with the images simply through their lyrical grace.

The monument as a whole is dynamic, and as we circumambulate it, taking time to gaze at and identify the art piece by piece, we find a freshness to our devotion and realization. At every turn the ultimate meaning of the temple is brought near to us, and the figures on the walls form the basis of our onward journey beyond the manifested world and toward the massive doors before the altar, where we will greet the Deity. When we are in the presence of the Deity, the power and impact of all the other figures seem to increase.

Before the Deity we halt, our eyes taking in the presence of the Supreme Lord. Having already been impressed by the many transcendental visions within the temple, our minds are arrested by the immortality of God’s form and are moved afresh by the beauty of the Divinity. Such an experience, repeated daily and regularly, cannot but have a lasting effect on us, what to speak of on the artists.

But now the local people have forgotten all this. And as a result the temples are dilapidated, dirty, and poorly attended. Comparing what once was with what now is, I felt a sinking feeling.

Yet, returning to the ISKCON Mayapur project that afternoon and seeing the temple bustling with guests, I took heart to see Srila Prabhupada’s influence in reviving and repopularizing Vedic culture. In addition to the terra cotta work I had already seen, I also saw the art the devotees were doing for Srila Prabhupada’s books, as well as the murals they were executing throughout ISKCON’s Mayapur community. Other devotees were making jewelry, ornaments, crowns, and elaborately embroidered garments for ISKCON Mayapur’s worshipable Deities. I saw devotees manufacturing karatalas and mrdangas (hand cymbals and clay drums), traditional instruments to accompany devotional chanting. Perhaps it’s not big enough to be called a renaissance, but it is big enough to create a spiritual revival in the lives of thousands throughout the world—who’ve found, through Krsna conscious art, literature, philosophy, and practice, a meaning and purpose to life. Previously, for me at least, such lofty ideals were nothing more than a castle in the sky.

Leave a Reply