Lynchburg, Tennessee

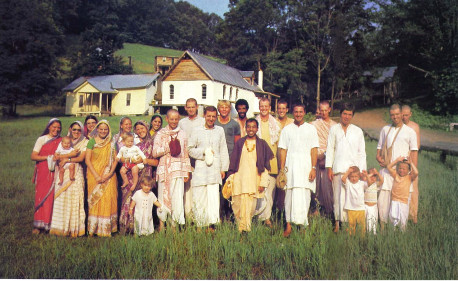

Here they tell us about their self-sufficient spiritual community in the Appalachian foothills.

by Mandalesvara dasa

name: Murari-sevaka, ” the place where everyone is a servant of Lord Krsna.”

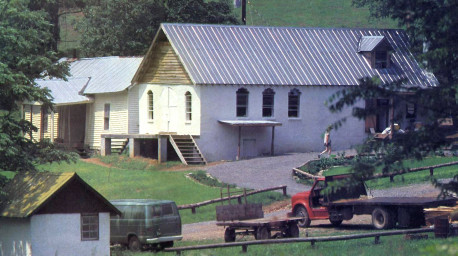

In the southern Appalachian foothills, near Lynchburg, Tennessee, you’ll find another kind of farming community.

In the southern Appalachian foothills, near Lynchburg, Tennessee, you’ll find another kind of farming community.

“We started out in 1976,” says Balavanta Dasa. “At first we figured we’d just plant corn or some other cash crop and make a lot of money for Krsna. But when I told our spiritual master Srila Prabhupada, he sat back thoughtfully and said, ‘Making money on our farm? That is a material idea. We don’t care about money—we just want to be self-sufficient.’

“Then it dawned on me. Srila Prabhupada didn’t want just an ordinary farm, and he certainly didn’t want an agribusiness. What he did want was a self-sufficient spiritual community where all kinds of people would want to live and work.”

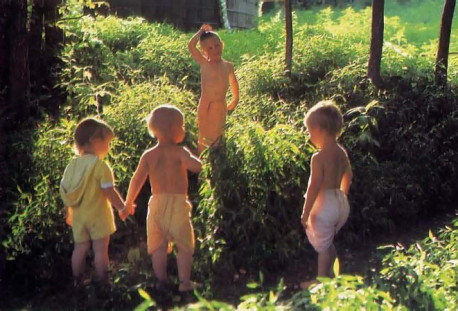

Nrsimhi-devi Dasi says she realizes most people think the community’s life must be quite hard. “But when you move out here you get your own house and if you want you can plant a garden Pure spring water comes right out of the tap, and the air is so fresh—no blue exhaust smoke.

“One day last spring,” she says, ” was sitting up on the front porch mending clothes. And I could hear the birds and the cowbells from all across the valley. I could even hear the breeze. My mind felt so clear—this was just the kind of place Krsna lived in. And I remembered when I was back in Chicago, just before I came to Krsna consciousness. was sewing then, too—out on the first escape overlooking the alley. And all could see was garbage cans and people coming out and dumping trash. All could hear was cars and trucks going by, and machines running and jets roaring overhead. Now, that’s what I call hard.”

Says Balavanta, “Some people think we’re just struggling along out here, while they’re enjoying their high standard of living back in the city. But just what is that ‘high standard of living’? A while back I was at a big political dinner in New York. John D. Rockefeller and his wife were there. But everybody was wearing synthetic suits. You know—the kind they make from petroleum by-products. And they were having frozen peas and cauliflower, coffee, brown-and-serve rolls, margarine …

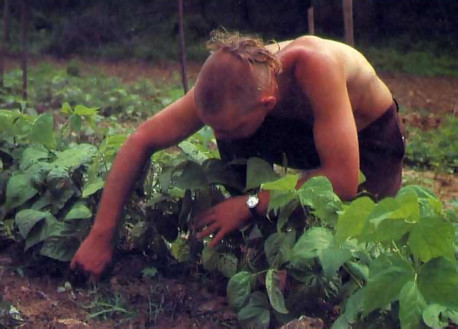

“Here on the farm we dress in pure cotton, wool, and silk. And we never have to eat any of that junk food. It’s all fresh—cauliflower and green peas right out of the garden, with just-ground spices and real butter. And the milk products out here are so rich and creamy—we call storebought milk ‘white water.’ “

Assistant coordinator Vedaguhya Dasa spent several years touring Third World countries. “Wherever I went—Latin America, Asia, North Africa—people really wanted to live on the land and keep some cows and do some plain, honest work. But the propaganda pushers keep them thinking they’ll be happier in the city, slaving in some factory or office building.

“When I came back to America,” he says, “I tried to get into the ecology movement, but my heart just wasn’t in it. To me, politics and legal maneuvers aren’t the best way to deal with the environment. I figured it would take a grassroots movement, spreading out from the individual to the family to the community to the whole society. Finally, a friend and I opened a vegetarian restaurant. We thought we’d save our money and buy a farm.

“Then one day I met Balavanta, and he told me all about Srila Prabhupada’s plan for starting Krsna conscious farms all over the world. So I gave whatever money I’d saved up, and that became the down payment for this place.”

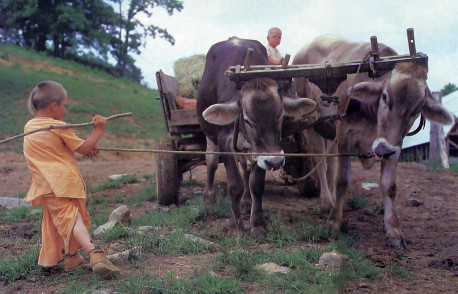

This is one farm community that treats the cow and bull with care. The reason: the cow provides milk and the bull plows the fields. “In a very real sense,” says Balavanta, “they play the role of mother and father….

“A few days back, I was walking behind Mother Kalindi, one of our cows. Now, in two daily milkings she gives about seventy pounds, so I knew she had to be carrying about thirty-five. She could hardly walk—what to speak of running away or defending herself. And she doesn’t drink a drop (even her calf can’t drink very much)—she gives all that extra milk for us! I mean, what are we going to do with the grass? But God has arranged that the cow takes it and turns it into milk, the miracle food. So we protect our mother. We don’t slaughter her.”

Some people think that animals have no soul and so it’s all right to slaughter them. Not true, says Sarvasiddhi-rat Dasa, who takes care of the herds.

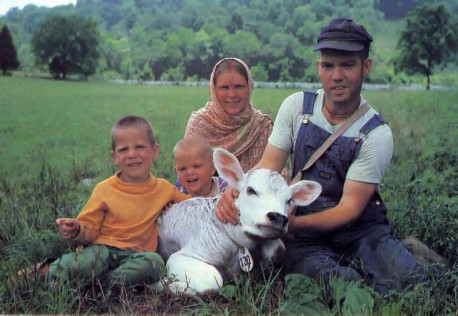

Svayamprabha-devi Dasi and Sarvasiddhi-rat Dasa , take care of the cows and bulls;

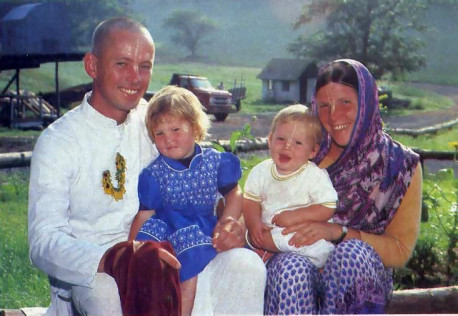

says Janmanjaya Dasa (right, with his wife Tara-devi Dasi and their children). “Why? Because we’re living a lot like they used io. Deep down inside, they all want to live on the land , be neighborly , and worship the Lord.”

forms of Lord Sri Krsna Caitanya and Lord Nityananda invite all to chant the Hare Krsna maha-mantra and offer the fruits of their labor

“A while back one of our cows died. The vet and I were both standing there. So I said, ‘What’s the difference between a living cow and this dead cow? The body is still there—all the chemicals. But where’s the life?’

“He couldn’t answer. Then I told him, ‘The life is in the soul, and when the soul leaves the body, so does the life. And it’s just like that with us, too. The life is in the soul. So the cow has a soul, and you have a soul. I wouldn’t kill you, and I wouldn’t kill a cow, either.’ He had to admit it made sense. We’re famous all over the county for not killing our cows or bulls.”

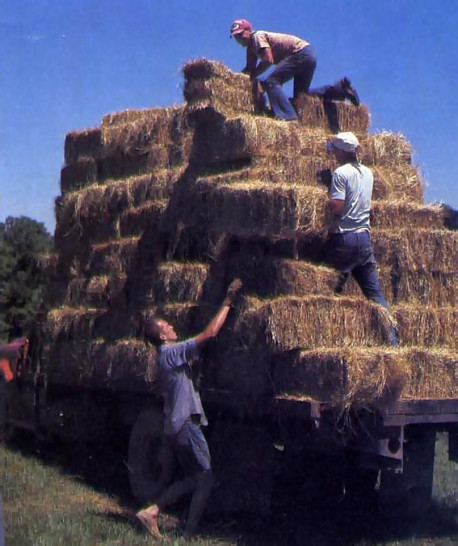

“You know,” Balavanta points out, “oxen do the same work as tractors and trucks—without all the ruckus and headaches. Sure, we’re still using a few machines, but before long we’re going to replace them all with animal power: We’re going to be totally self-sufficient. You might save a little time with a tractor, but you’ve got to spend a lot more time working to pay for it. Then the blasted thing breaks down—maybe right in the middle of spring planting—so you have to haul it into the shop, and they have to ship the part in from halfway across the country. Meanwhile, you’re standing there twiddling your thumbs.

“Lots of cows and bulls and lots of grain—that’s he sign of a healthy economy. But today most farmers lean so much on machines and oil products that when an energy crisis comes, they don’t know what to do.”

“I’ve talked a lot with our neighbors,” says Janmanjaya Dasa, the community’s president. “And they have some surprising things to say. Take Mr. Durham. He told me plenty of people are watching our community. Why? Because we’re living a lot like they used to. Deep down inside, they all want to live on the land, be neighborly, and worship the Lord.”

Just as in old India, the community’s life centers on the temple. After spending the day in the fields and pastures, everyone comes together in the evening to hear narrations about Krsna, chant Krsna’s names, and dance in ecstasy. “This farm belongs to Krsna,” says Titiksa-devi Dasi, “and everybody here knows that. God is everywhere, and He owns everything, so we’re all working to please Him. The cows are giving their milk, the cooks are preparing food, the gardeners are growing fruit, vegetables, and flowers—all of us are working to please Krsna.”

Could this way of living be too old-fashioned for people today?

“Well,” says Balavanta, “one time in India I was walking with Srila Prabhupada when a farmer came up the road. He was chanting Hare Krsna, and he bowed at Srila Prabhupada’s feet. They exchanged a few words in Hindi, and later Srila Prabhupada told me that the farmers in India know more than the biggest philosophers in the West. This farmer knew there’s a God. He knew he’d had past lives. He also knew that depending on his karma—what he did in this life—he’d get another body. And he knew that if he’s thinking of Krsna when he passes away, he’ll go to Krsna in the spiritual world. He was a farmer, that’s all. Yet he understood such a deep thing—he knew why he was here.”

all glories to those who follow prabhupada’s instructions!

Can we get some cowdung patties for my agnihotra?