Religious Persecution In West Germany

The raid . . . the media barrage . . . the courtroom encounter.

A half-million-dollar effort to snuff out the Hare Krsna Movement.

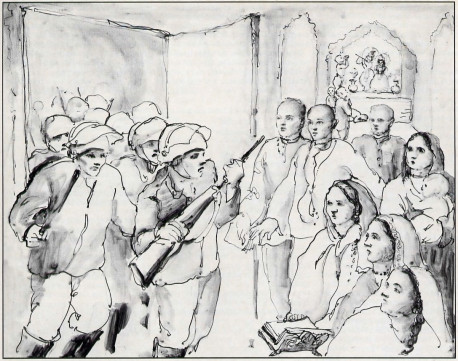

The searchlights flickering on the refectory walls didn’t phase anyone very much. It was just after 8 a.m on Sunday, December 14, 1974, and the hot cereal with fruit and milk had top priority for the roughly seventy devotees at the hilltop Krsna center in the south German countryside. But soon one of them asked, “What’s going on?” and another went to the window.

“The whole driveway is filled with police cars,” the young man said, “—all the way down, as far as you can see.”

Most of the devotees kept focused on their breakfast, though a few more went to the windows. More policemen were getting out of their green and white cars and making their way up the hill. They had guns, shields, gas masks, and helmets with face guards, and in a moment they had the place surrounded.

Blond, blue-eyed Maharathi dasa opened a window and asked, “Why have you come?”

One of the officers shot some tear gas his way. Before anyone could open the doors, they had broken in and were storming through the halls with their boots and machine guns, looking into open cabinets and closets and breaking open the locked ones.

When Maharathi had washed his eyes, he asked the policemen not to smoke inside the temple.

“If you don’t be quiet,” one of them offered, “we’ll knock out your teeth.”

When the police reached the women’s quarters, they threw saris on the floor and laced them with oil. One policeman announced, “This is my harem,” and another addressed the celibate girls as “beautiful prostitutes.” When one of the girls objected, a policeman warned, “Be careful, you cow. Otherwise, I’ll hit you in the face so hard you’ll think a horse has kicked you.”

Searching the house, the police came upon two shotguns and a Colt pistol and confiscated them. Then they broke into the treasury and confiscated the donations collected in past weeks. Soon they started smashing everything in sight—walls, doors, chairs, windows.

After an hour or so, they marched the devotees out through the snow and into vans. One devotee didn’t even get time to grab his shoes.

“My wife is seven months pregnant,” another devotee explained. “Couldn’t she just stay here?”

Four policemen locked his arms behind his back, pushed him outside, smashed his head several times into the side of a police car, and threw him inside. They put his wife into another car.

Standing outside with his arms folded, supervising the proceedings, was Mr. Hans-Gero Schomberg, the local Staatsanwalt (state attorney). He was a tall, good-looking young man, and at his invitation about a dozen reporters and photographers were on hand to cover the story for the next day’s front pages.

An hour later, when the police vans unloaded the devotees at the Frankfurt jail, the reporters were waiting for them again. One by one, the devotees went through fingerprinting, mug shots, and interrogation. Then the police let them go—except for the leaders. These two devotees they kept in jail for six weeks.

That evening, while the Krsna leaders held on to their cell bars, the Staatsanwalt held a press conference, and within hours the whole country knew—”Hare Krsna Criminals,” “Frauds,” “Kidnappers,” “Gangsters.”

History of Harassment

Not that they’d ever gotten great press. Since back in 1968, when the Krsna movement first appeared on German soil, the devotees had always been portrayed as a little kooky at best. And now that their members and their distribution of books and their collections had increased, so had a sense of alarm, particularly among certain churchmen (the local counterparts of America’s waning “anti-cult” crusaders).

Chief among these men was Father Friedrich-Wilhelm Haack, the “Commissioner for Questions on Sects and Ideologies” for one of the country’s largest denominations. He and the others kept the press well supplied with pronouncements on how the apparently innocent Hare Krsna devotees were in fact brainwashers, frauds, and criminals. With Father Haack’s encouragement, a Berlin police inspector whose son had joined the movement wrote an article depicting the devotees as fanatics more crazed and dangerous than the Baader-Meinhof gang. The article ran first in the Kriminalist, a periodical for law-enforcement officials, and soon it was picked up by newspapers all over the country.

Not long after, the illustrated weekly Stern ran a sensationalistic story about life in a Hare Krsna temple.

“This young fellow had come to visit,” explains Dutch-born Prthu dasa, thirty-two. “He said he used to live in a monastery, and he asked to join us. But after some days he left, and then we saw his name on a really nasty ‘inside’ story. It made us look like some kind of Manson-styled loonies. Really outrageous nonsense.

“Those two articles created a small frenzy. And finally some village mayor wrote to the Frankfurt District Attorney and demanded that something be done. That’s what eventually led to the raid on our temple.”

At the time of the raid, the coordinator for the Krsna movement in Germany was Hamsaduta Svami, thirty-seven, who happened to be visiting America. “The temple leaders were in jail,” he said, “I was out of the country, and Prthu was in Amsterdam. So the devotees had no leader. It was like a ship without a captain in a stormy sea. I mean, overnight our reputation was shattered. And anyone who had any connection with us—the milkman, the gas man, the garbage man—they just cut us off. The gas man came in the middle of the night and took all the gas bottles. The milkman took his milk cans, and we were just cut off from everything.”

“Our treasurer went to the bank to withdraw some money so we could keep functioning,” another devotee related. “But armed guards blocked him at the door—illegally, we later found out—and there was nothing we could do. And then two days later the authorities got a restraining order that froze our account.”

The temple leaders had to stay in jail for six weeks. Wasn’t there any bail? “Fifty thousand marks apiece,” says Sucandra, thirty-one, who was one of the two devotees held. “That’s about twenty-five thousand dollars each—more than they ask even for murderers.” And the other devotees didn’t know how to get their leaders out. Lawyers asked for hefty fees in advance and then said that nothing could be done.

“But after six weeks,” says Sucandra, “they were really anxious to get us out of there. They didn’t have any real grounds for holding us, and it was stretching on and on and beginning to look ridiculous—keeping us separate and so on. So one day they just accepted the bail and let us go.”

Must a Monk Be a Blithering Idiot?

What were the devotees accused of? No one actually knew. Says Prthu, “We didn’t get the indictment until the end of November 1976—two years later. For two full years, they just kept us guessing. ‘When is this case going to come to court?’ we’d ask. And they’d say, ‘Oh, maybe next month. We’re still working on the investigation.’ And during this whole time, all our funds were frozen, and we’d always be getting blasted in the press. And everyone on the streets would simply echo whatever the newspapers said.”

Another devotee explains, “For two years we never went out with robes or shaven heads. We were always fearful. … People on the street would come up and spit on us or smash our cars. Or after we’d been distributing books, a policeman would come and take away all the donations. In Berlin someone even sprayed our temple with a machine gun. It was only by the mercy of Krsna that the temple president bent down and the shots went over his head.”

(A few years earlier, a gang of Rockers had stormed the Krsna temple in Hamburg with knives, bats, and brass knuckles. The devotees; warned of the attack, had called the police for help-the police station was just around the corner—but as Hamsaduta put it, “The police would say, ‘Well, you know, we can’t answer every little call.’ ” The devotees somehow fought off the Rockers by themselves and then applied for a gun permit. When the authorities without explanation refused the permit, the temple president decided that his first duty was to protect the devotees, so he purchased some light arms anyway. These were the guns the police later found when they raided the temple near Frankfurt.)

Rockers weren’t the only ones who gave the devotees trouble. “Even the police would harass us,” Prthu says. “They seemed to think it was their sacred duty to beat the devotees—physically beat them and throw them in jail.”

Finally, the devotees received the indictment. “They charged us with everything they could think of,” says Hamsaduta Svami. “Theft, kidnapping, fraud—they threw in as much as they could. The main thing was that they tried to make Krsna consciousness look like some sort of underworld business empire. But their indictment hardly seemed like something they’d been cooking up for two years. It was all kind of thrown together. And much of it was just copied almost verbatim from thai original slanderous article in the Kriminalist.”

Their main target, though, was money. Not just a little money, either. “They took about 700,000 marks,” says Prthu. “That’s about 340,000 dollars. The money was there to print books, to purchase food for our relief programs in India, and to support our other programs for spreading Krsna consciousness. But the government was monitoring the accounts, and they saw all this money going in and out. So they said, ‘Now we’ve got to take away this money.’

“That’s the main focus, the main emphasis—this money. They were simply envious because we had this money, even though we don’t use it for ourselves. They think a God conscious person should have no money. But must a monk or a holy person be just some blithering idiot who can’t do anything? Is it a crime that we’re intelligent, that we’re successful in distributing our books, collecting funds, and spreading Krsna consciousness?

“The whole case is centered on taking the money, not on any criminality. The criminality was simply their excuse. They made up all the accusations just to keep the money. So it’s actually a case of simple theft. They didn’t even care if they were right or wrong—they simply took the money first, and then it took them two years to figure out what to charge us with. They didn’t like the fact that we had collected so much money, and they wanted to keep it—that’s all. Plain and simple.”

Dancing Into Court

When it finally came time for the trial, the devotees had managed to find lawyers who it seemed wouldn’t cheat them, and so they were ready to go. Now it was December of 1977.

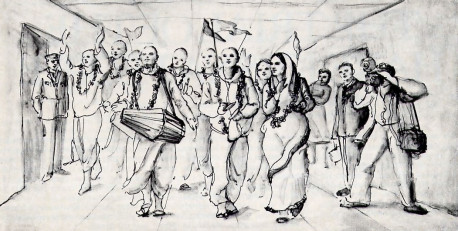

Says Hamsaduta Svami, “The Staatsanwalt was telling everybody, ‘They won’t even show up. They won’t even come to court.’ Everyone was already there—the lawyers, the judges, the visitors, the Staatsanwalt. We were the only ones who weren’t there. So everyone was a little on edge.

“Then about twenty-five or thirty of us came up to those somber old court buildings chanting Hare Krsna full blast, with drums and cymbals. They’d never seen anything like it—the defendants coming to court singing and dancing and wearing flower garlands. All the windows opened, and the curtains went back. People were sticking their heads out, and we were waving like soldiers just back from a victory.

“After maybe ten minutes of chanting, we went into the courtroom, and everybody seemed to be smiling. They also seemed pleasantly surprised when the ten of us who were actual defendants sat down in our places, put pictures of Krsna and Srila Prabhupada on the bench before us, and made little altars with flowers. Otherwise, it looked a lot like the Nuremberg trials… two lawyers and a microphone behind each defendant—the whole works.”

The Accuser Becomes the Accused

From the beginning, the devotees wanted to avoid complex legal arguments and instead speak out about Krsna and the authenticity of the Krsna consciousness movement. In that way, they reasoned, even if they lost the case, the public would get a chance to hear what they really wanted to say.

“I’d felt all along,” says Hamsaduta Svami, “that this whole affair was Krsna’s arrangement. He hadn’t forgotten about us. He’d actually been making an arrangement to glorify His devotees and push His movement forward. Otherwise, people might not have been interested. But this big raid and the slander in the press had fascinated them, and now we wanted them to find out just what our movement is all about, to find out that the devotees are actually following an ancient culture of spiritual science and philosophy. And that’s exactly what we wanted the judges to find out, too.”

Accordingly, the defense lawyers made a prompt motion that the judges (who for three years had read only the press reports) should now examine at least portions of the books upon which the movement is based—ancient India’s Vedic scriptures. The judges accepted the motion, and the lawyers handed them German translations of Bhagavad-gita As It Is and Srimad-Bhagavatam. After that the judges would often be seen reading while the case was going on.

In German courts the defense presents its case first, and then the prosecution. So one after another, the devotees got up and presented their statements. Hamsaduta Svami began.

“The thing that distinguishes a human being from an animal,” he said, “is religion. Religion is the basis of law, which is the foundation of civilization. Without religion there is no duty, no standard of behavior, and no purpose or direction for human civilization.

“The greatest men in history were not businessmen, politicians, scientists, Stalins, Hitlers, or Napoleons. They were men dedicated to God—Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, Caitanya. Great men are those who have dedicated their lives to the service of God by preaching His message in the world.

“In the Srimad-Bhagavatam it is said that great souls live not for their own satisfaction but for the welfare of others. It is because of such pure devotees that there is light and hope in the world. Such pure devotees are called mahatmas, broadminded souls. Now, I ask you whether the Staatsanwalt is a mahatma, a pure devotee of the Lord.”

At this the audience—perhaps a hundred reporters and other onlookers—burst into laughter. The Staatsanwalt turned red.

Hamsaduta Svami continued, “What is the character of this man? How can he dare impugn the integrity of Hare Krsna monks who have dedicated life and soul to spreading God consciousness? They daily accept insult and even risk personal injury in their attempt to uplift human society by distributing books on the science of love of God. Does it matter, then, if they collect two thousand or two million or even two hundred million marks to carry on their mission?

“If collecting money were our purpose, distributing God consciousness would be the wrong line. Better that we had gone in for distributing pornography or heroin. We could have offered anything other than love of God and spared ourselves a lot of trouble.

“It is the duty of the government not to suppress but to protect and uphold the principles of religion—cleanliness, truthfulness, austerity, and mercy—for human society without religion is no better than animal society.”

Then Hamsaduta Svami directly countered the charges and their author, the Staatsanwalt. (A portion of his statement appears at below.)

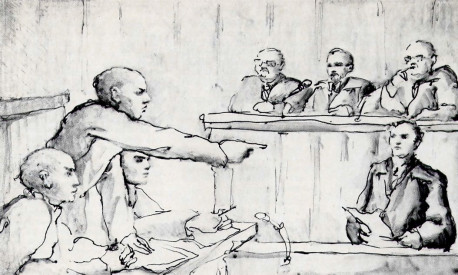

Now Prthu spoke.

“This is the same thing that happened thirty-five years ago,” he said. “The same injustice, the same closing of the eyes. The same blind following, the same abuse of freedom.

“The Jews were involved with money, and Hitler wanted to control it. So first he called them criminals, and then he sent them off to concentration camps.

“When Hitler came to power, the Church made an agreement with the government that the churches wouldn’t work against the government and the government wouldn’t bother the churches. This was the Concordat. And immediately afterward, the Nazis stamped down upon so many sects. The Jehovah’s Witnesses—they went into the concentration camps. The Jews went into concentration camps. Even church members who stood up against the government were harassed—and the church didn’t do anything about it.

“My father…” Prthu’s voice shook with feeling. “My father was a Dutchman. . . . We were living in Germany in a little village, and Hitler was coming the next day, so everyone was ordered to hang out a flag. The only person who didn’t do it was my father. That night they came and look him away—put him into a concentration camp.

“And now for three years this rascal, this rogue, this liar…” Prthu pointed at the Staatsanwalt, who stood up and objected. The judge overruled him. “It’s the same thing,” Prthu continued. “In the 1930’s they ran so much propaganda against the Jews that people smashed the synagogues. And now again there’s so much lying propaganda that people raid our Krsna temples and assault our devotees in the street. People from the churches have asked the government to help stifle our Krsna conscious activities, and that’s just what’s happening. Now the state has branded our monks criminals, so that they can seize our funds and drive us out. It’s the same thing, the same style. Who can mistake it?

Hamsaduta Svami had spoken two hours, and Prthu spoke four. Then court adjourned for the day.

For the first time, the devotees had created a favorable impression in the press. The newspapers described them as relaxed, peaceful, cheerful, and clean. Said the Frankfurter Rundschau, “The impact of the defense of the Hare Krsna monks was so overwhelming that it dominated the whole atmosphere of the courtroom. It appeared that the state attorney was standing quite alone and helpless with his accusation files in hand.”

“They turned the court into a tribunal,” said the Frankfurter Allgemeine, “and suddenly the accuser became the accused.”

“Preaching Is Our Life”

The next day of the trial began with the devotees’ children distributing cookies around the courtroom. After that they did it every day. Says Hamsaduta Svami, “One little boy would walk around fearlessly and offer cookies to the prosecutor and the judges, and they couldn’t refuse. The defense lawyers would pass the cookies around among themselves. One day the prosecutor complained to the judge that I was eating cookies, so all the lawyers made mock-choking sounds, and my lawyer said, ‘I cannot tell a lie. I, too, am eating a cookie.’ “

When court went into session, Sucandra spoke again about what many people cared about most—the money. Now, the German states have laws that tightly rein the soliciting of funds. But one section of the national collection laws says, “Churches, religious societies, and ideological societies are exempted” from these laws, “and also exempt are religious orders and religious congregations that use the funds collected for maintaining their livelihood.”

The Staatsanwalt, however, had contended that the Hare Krsna movement was not a religion at all, but a kind of shrewd business organization.

“When our devotees go out,” Sucandra countered, “they never think, ‘I am collecting money.’ Instead, they think, ‘I am distributing love of God.’ What we do is completely different from ordinary collecting—because when we go out our purpose is to give people something (a book or record) that will inspire their love for God. And if we’re going to keep printing books and making records, people have to give some donations. Otherwise, if we just gave all these things away, we’d eventually go broke. That’s only common sense.

“So we’re going out and giving people something beneficial, and naturally they’re giving whatever they can. That way we can print more books and keep our mission going.

“We see that materialistic life is making people suffer. So our mission is to print these books in the German language so that people can learn how to become free from suffering and attain the highest perfection of human life.

“What do we do with the money? We don’t try to gratify our senses. We just use it to spread God consciousness to people all over the world.

“We sent fifteen thousand marks to India for food distribution, and we also sponsor the distribution of food and books in Africa and the Middle East. And then we also take a little money to live on—five percent. The police who dug into our finances were amazed. Five percent—practically nothing,

“But the Staatsanwalt wants to twist the laws to say that a religion may collect only for its livelihood, and nothing more. If we’d spent ninety-five percent for eating, sleeping and having a nice time for ourselves—for our ‘livelihood’—that would presumably have been all right.

“But we don’t do that. Every one of us sleeps on the floor. It’s very simple—a Krsna conscious life. And we like it. We do it voluntarily. But we’re being penalized for being so austere!

“Our livelihood—our life—is preaching. Unless we’re preaching—unless we’re printing and distributing books—we can’t live, because that’s our whole purpose, our whole mission.

“To perform sankirtana—to give people our books and accept some contribution—is our constitutional right. If you don’t allow it, we’re ready to die doing sankirtana, but we will not stop, no matter what you do. Whether we win this case or lose it, we’ll continue to distribute our books and help people find out about Krsna, because this is our religious right. It’s our right, and we will not stop. It’s not a part of our religion; it is our religion. In all the Vedic scriptures you’ll find this confirmed.”

Emphasizing the scriptural authenticity of the Hare Krsna movement was Vedavyasa dasa, twenty-six, the final defendant to testify. It was he who had translated the scriptures of the Krsna consciousness movement into German, and now he gave a careful, scholarly explanation of their history and purpose.

But he, too, was indignant. “The Staatsanwalt has gotten a statement from my mother saying that I’m a demented, demoralized robot, a moron,” he began. “But I’ve translated these books”—he pointed to a full set of Vedic writings, lined up on a table before him—”and they’ve won the praise of scholars and professors throughout Germany. Do you think this is the work of a moron?” Judge Franz answered by spending the better part of the afternoon reading Srimad-Bhagavatam, and at the end of the day he took a full set with him. Chief Judge Maul took a copy of Bhagavad-gita.

Later the judges requested to see a film about the movement, and the defense rested its case.

“A Cow on Ice”

Now the Staatsanwalt faced a difficult task. He had to shake apart the credibility the devotees had so quickly established. “I just want to show you,” he said, “that these people are not the angels they’ve impressed you as being.” He had 131 witnesses, and so he began his case.

“During the time you worked for these people,” he asked a man who had been the devotees’ bookkeeper, “did you feel they were purposely conducting fraudulent activities?”

“No,” the man answered. “I never had any idea like that. That was the furthest thing from my mind. Why, they’re the most friendly, warmhearted people. Anyone who comes to them immediately gets a meal. …”

The Staatsanwalt called another man.

“I was on the street,” the man testified, “and a young man approached me. We talked for awhile, he gave me a book, and I gave him a donation.”

“Did you feel like you were being cheated?” the Staatsanwalt asked.

“No.”

“Why did you give a contribution?”

“Well, I thought he was giving me something nice, so I should also give him something.”

The Staatsanwalt called another witness. Apparently he hadn’t screened them beforehand.

“I was very interested in the book,” the witness said. “Later I got more of them. And you know, I still read them today.”

Says Hamsaduta Svami, “It was as if Krsna were putting the words into their mouths. They would speak in such a way as to support everything we had already said in our defense.”

The Staatsanwalt’s case was beginning to crumble. As the Nord Stuttgarter Rundschau put it, “What had appeared to be a band of criminal monsters had turned out, to the amazement of everyone, to be nothing more than a band of cookie monsters whose only crime appeared to be distributing and eating cookies in the courtroom.”

Another incident concerned a fourteen-year-old boy the devotees had supposedly kidnapped and hidden away in America. By now he was eighteen, and the Staatsanwalt called him as a witness. But the boy asserted that he had actually slipped away from his drunken mother and had run off by himself to Amsterdam. “And right there on the spot,” says Hamsaduta Svami, “the Staatsanwalt had the boy handcuffed and arrested for suspicion of perjury, and he hauled him out of court. It was unprecedented. Even if a man is flat-out lying you don’t do that. The judges were furious. But they couldn’t do anything, because technically it was legal.”

By now the Staatsanwalt’s colleagues were calling him “a cow on ice” and wondering how to get him off. The devotees compared him with the hapless Michael Schwed, an assistant district attorney in Queens, New York. In 1977, amid great fanfare in the media, Mr. Schwed had prosecuted two Hare Krsna devotees on unprecedented charges of “kidnapping through mind control and brainwashing.” (Mr. Schwed’s colleagues berated him for making “a laughingstock” of the D.A.’s office, the State Supreme Court threw out his indictments and said he had garnered “not a scintilla of evidence,” and the judge certified the Hare Krsna movement as “a bona fide religion with roots in India that go back thousands of years.”)

Soon the press handed the Staatsanwalt his share of criticism. “The prosecution could not avoid the impression of religious persecution,” said the Frankfurter Rundschau. “Too often, as the defense rightly mentioned, the prosecution has called something humbug that is in fact holy to these monks.”

But the bad notices really started coming in when newsmen realized how much the trial of the Hare Krsna people was going to cost. “One million marks,” says Prthu. “It cost one million marks—nearly half a million dollars—for them to prosecute us. Which means their raid hadn’t even gotten them enough money to pay the court costs.

“It was a big scandal all over the newspapers. The newsmen figured it out. Our lawyers were court-appointed, and the state had to pay five hundred marks a day for each of them. There were ten defendants, and according to German law, each defendant had to have two lawyers. And there was the salary for the Staalsanwalt and his assistant, the guards at the door, five judges, the P.A. system, and the guy who wrote everything down. Then there was the cost of the police raid—all those policemen working overtime. Huge expense! They paid one million marks to prosecute us for ‘illegal collection,’ an offense that’s really on the same level as illegal parking. And that’s why they had to have the money—to pay for the court case.”

Peculiar Testimony

Finally the Staatsanwalt called his star witness, the same Father Haack who had gotten the case going in the first place.

“That was a big day,” recalls Hamsaduta Svami. “All the newspapers were there. Everyone was expecting that he was really going to let the cat out of the bag and tell everyone the real dirt about the Hare Krsna people.”

The Father, it seemed, had a large collection of file cards recording his encounters with devotees on the streets. The cards gave the date, the time, and what had actually happened. “Whenever I would meet one of them,” the Father said, “I would note it down.” Then he proceeded to detail various nasty charges against the devotees.

“It looked really bad for us,” says Hamsaduta Svami. “But before he left the courtroom, one of my lawyers—it was just Krsna’s mercy—remembered something.”

“I have a few questions,” the lawyer said. “I find your statements very peculiar in light of the statements you made to the police three years ago. After the investigating officer interviewed you, he wrote down in his report that you could give no substantial information. According to his report, everything you said was from hearsay. And there was no mention of any cards. How is that?”

The witness became flustered. Perhaps the policeman hadn’t asked the right questions, he suggested.

“Do you remember that policeman?” the lawyer asked,

The witness didn’t really remember. After all, policemen came to him often. If he had come, it might have been for only a few minutes, ten or fifteen.

“Try to remember,” the lawyer kept saying. “Such a big case, you were so concerned, and you’d been keeping the file cards. Surely you must remember.”

But the witness didn’t remember, and finally he was excused.

Then the policeman was called to the stand. “Now, we want to know what connection you had with this priest,” the lawyer said.

“Oh, yes. I remember him well. We often spoke together on the telephone.”

“When you visited him, how much time did you spend with him—five minutes, ten minutes, half an hour?”

“Oh, we spent at least three or four hours together.”

“And why did you write that he couldn’t offer anything but hearsay?”

“Because it was a fact. He was just relating incidents he’d heard from other people.”

Then the lawyer asked, “If this man had kept file cards, let’s say, with information of meetings at definite times, would you have noted that in your report?”

“Definitely! That would have been something, at last. But he had nothing. He was just talking about things he’d read or heard.”

Hot Air and Superior Forces

“Since the evidence showed that the Staatsanwalt had produced an excess of hot air,” reported the Frankfurter Allgemeine, “Judge Maul finally proposed to put an end to the case because of its disproportionate insignificance.”

Yet on the last day of the proceedings, just before the judges retired to consider their verdict, they heard the testimony of Professor Klaus Finkelburg, one of Germany’s leading constitutional lawyers. The State had pointed out all along that when the Hare Krsna movement registered ten years ago, it was as a charitable organization, not as a religion. But, asked Dr. Finkelburg, did this mean the Hare Krsna movement had forfeited the constitutional rights guaranteed to every other religion? Registration was such a fine technical procedure that even Dr. Finkelburg and his colleagues had no idea how to go about it.

If the court actually wanted to reach a decision, Dr. Finkelburg submitted, it must first send the case to the constitutional court. They would determine whether Krsna consciousness is a genuine religion and whether sankirtana, the movement’s preaching work, comes within the scope of religious activity. Only then, he said, might the lower court resolve this case.

Still, on April 28, 1978, the court announced its verdict.

To the Staatsanwalt’s chagrin, the judges absolved the devotees of all criminal charges. (The only exception: for illegal possession of weapons they gave the president of the Frankfurt temple a six-month sentence—and then suspended it.)

The judges noted that the only charge with possible substance was violation of the collection laws, and here they did not hold back their criticism of the prosecution. “Violations of the collection laws,” said Chief Judge Helmut Maul, “should have been dealt with in a less extravagant way—for example, by fines—and not by the use of a four-month trial with more than thirty days in court.

“But higher-ups,” Judge Maul said, “insisted that the trial take place.”

The Hare Krsna movement, the judges agreed, was a bona fide religion—yet it was not a religion in the usual Western sense of the word and thus was not in the same category as the established churches.

Accordingly, the judges fined three devotees five thousand marks each and one devotee twenty-five hundred marks. Also, the court ruled, the confiscated donations would not be returned.

Although it wasn’t in the written verdict, Judge Maul said one thing more: “Superior forces from outside this court have played a role in the finding of this verdict,”

The judges seemed depressed. “They didn’t want to look us in the eye,” says Prthu.

“I don’t like this decision at all,” one judge said later. “We were forced to do this. We didn’t make that decision.”

On basic constitutional grounds the Hare Krsna devotees have appealed to a higher court. There they expect at least two years’ delay, and then, eventually, vindication.

[…] From the Back2Godhead.com website […]

Wowwwww! Sadhu Sadhu!!!!! What an article! This can give us a glimpse of how many difficulties Srila Prabhupada and his dedicates soldiers faced and how they came out of them winning like a Lotus comes out of mud!

The incident in the court reminded me of the most famous trials of Modern Indian History of great patriots – Bhagatsing, Rajguru, Sukhdev and thier other comrades. They also utilised the court proceedings for spreading their voice in the mass.

I have always been fascinated and inspired by thir courage and intelligence. But by reading this incident I can say that, the Hare Krishna Patriots and revolutionaries are not less than those great men, rather these are dedicated to the eternal welfare of the souls, hence their act is perfect!

Jay Prabhupada, Jay Gaura Bhaktas!!!!

Your Servant,

Narsimharupa Das,

ISKCON Pune Congregation

[…] The Trial of the Hare Krsna People in Germany […]