A look at who we are, why we read the news,

and what we’re missing.

by Mathuresa Dasa

Reading the newspaper this morning: Officials at the University of Nevada have OK’d a site in Reno for a sheepherder monument. Two young female tourists have drifted ashore in their disabled motorboat near Jakarta, Indonesia, after living for twenty-two days on short rations and rainwater. And Israeli foreign minister Itzhak Shamir has announced plans to release a group of Shiite Moslem prisoners. Some stories are more earthshaking than others, but apparently none of them is worth much. It will all soon be old news, and most papers will lie crumpled in wastebaskets from Jakarta to Reno.

Yet despite the fleeting value of newspaper tidings, we’re hooked. Tomorrow millions of us will have our noses buried in the latest editions, again reading all about who did what when, where, and how.

We need to hear about people. That as much accounts for our addiction to the daily papers as does our need to know about events that might directly affect our lives. How does a sheepherder monument affect us anyway? In the papers we find people talking, people fighting, people buying, selling, voting, getting married, dying. It’s endless. People make the news. They people the papers.

At least at some point in our lives, each of us, stepping back to survey the overall phenomenon of peopledom, has asked, “What exactly are people?” or “What is a person?” The same question may also arise in the form of “Who am I?” But it must arise, because self-examination is part of being a person.

The Bhagavad-gita declares that out of millions of human beings, one may be serious enough about self-examination to devote full time to the people, or person, question. Perhaps the late Gordon Allport was one such rare soul. In his book Personality: A Psychological Interpretation, he traced the long history of the concepts of personhood and personality and compiled a list of fifty definitions, including one of his own. Even after all that tracing, however, Allport’s definition is vague—nothing I’d want to repeat here, nothing to divert your attention from those juicy headlines.

More definitive than Allport’s definition was this statement of his:

Personality is one of the most abstract words in our language, and like any abstract word suffering from excessive use, its connotative significance is very broad, its denotative significance negligible.

Allport also quotes F. Max Muller

“Let us consider the word person. Nothing could be more abstract. It is neither male nor female, neither young nor old. In French it may even come to mean nobody. For if we ask our concierge in Paris whether anybody has called on us during our absence, he will reply, ‘Personne, monsieur,’ which means, ‘Not a soul, sir.”‘

In short, although the terms “person,” “personality,” and “people” conjure up a lot of things in our minds, nobody can say for sure what a person is. The Gita therefore declares that even among those rare souls who dedicate themselves to the people question, hardly anyone obtains a perfect answer.

So why go to so much trouble? Most of us, after all, are newspaper buffs, not psychologists or etymologists. Why not just accept that persons is what we are, and that one aspect of our personalities, as evidenced by our dependence on a daily dose of newsprint, is the need to hear about other persons? Instead of bothering to define “person,” let’s go ahead and answer the person question by experiencing our own personhood. Give us action. Give us headlines!

But wait. Not so fast. In the Gita and other Vedic literature, Lord Krsna and the Vedic sages give us both a clear definition of “person” and an elaborate description of how to actively experience our full personhood.

The Gita’s first definition is negative: a person is not the material body, not temporary flesh and bone, but an eternal individual who, for now, resides in the fleshly tabernacle, falsely identifying with it. Unlike the body, the person is indestructible and “can never be cut into pieces by any weapon, nor burned by fire, nor moistened by water, nor withered by wind” (Bg. 2.23). Our bodies, the Gita points out, change from childhood to old age, but our selves remain the same, observing the changes.

Returning to our daily paper, is this negative definition very practical? The true person, we now understand, is not a sheepherder, not a prime minister, not a young woman adrift in the Indonesian archipelago, but a resident of a particular body with which it falsely identifies. But what does this person look like? What does it do? What can we report about such a negative entity? The true person may be more durable than its bodily abode, but it isn’t at all newsworthy. Again, we need action, headlines, positive identification.

So in the Gita Lord Krsna also gives us a positive definition. “All living entities,” He says, “are My eternal fragmental parts” (Bg. 15.7). Krsna is the Supreme Person, the Absolute Truth, the origin of everything. All other persons, without exception, are eternally part and parcel of Him, just as leaves are part and parcel of a tree.

Thus the consummate definition of person is “an eternal part of Krsna, the Supreme Person.” Since there is nothing beyond Krsna, there is no better definition than this.

What?! But we still don’t know what person means. You’ve only told us who the Supreme Person is and where we stand in relation to Him.

But that is as far as definitions go. So now is the time to abandon definition hunting and get down to the business of experiencing our personhood. And since we are part and parcel of Krsna, the perfection of such experience is to hear about and interact with Him. Hearing about, talking about, remembering, and serving Krsna under the direction of the Vedic literature is known as bhakti-yoga, the science of getting to know the Supreme Person through devotion. As we get to know Krsna, we also understand ourselves, because we are tiny “samples” of Him.

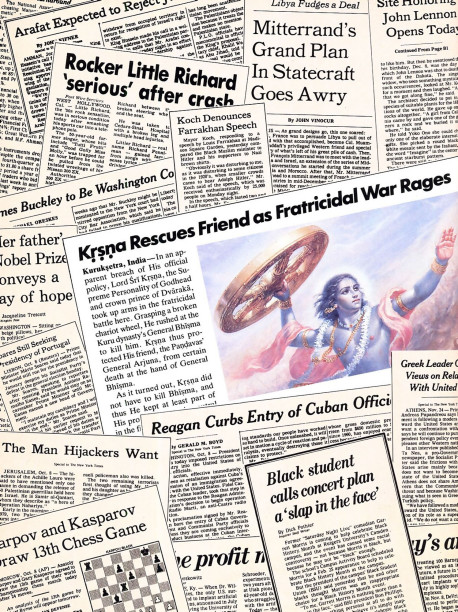

Unlike the “negative person,” Krsna and His devotees are supremely newsworthy. The Vedic literature overflows with descriptions of their activities, their fame, their teachings, their beauty, their wealth, their loving dealings. The Gita itself is one chapter in a blow-by-blow account of Krsna’s successful bid to establish a peaceful, prosperous, and spiritually productive world community. And since news of Krsna is eternally relevant to every person, you never need to trash it.

So for action, for headlines, we should bury our noses in news of Krsna. Ordinary news gives us an inkling of a person’s bodily experiences. But since we are not these bodies, we ought to take more interest in our spiritual potential as Krsna’s servants.

Keep those presses rolling. People the papers. But let us hear about the Supreme Person and His devotees.

Leave a Reply