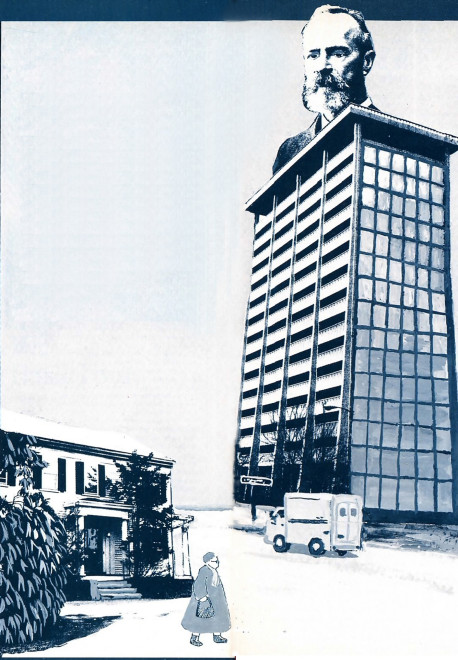

William James’s “Soul Theory” seemed imposing at first—as imposing as William James Hall must have looked to my grandmother. As it turned out, James was pretty close to home.

by Mathuresa Dasa

Gammy, my grandmother, had a passing acquaintance of sorts with William James, the great American psychologist and philosopher. She owned a two-century-old white clapboard house on Kirkland Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and in the early sixties Harvard University erected William James Hall on the lot across the street. As a good neighbor, Harvard invited my grandmother to a party celebrating the opening of this fifteen-story concrete-and-glass home for its psychology department. Gammy crossed Kirkland Street on rickety legs, rode the elevator to the top floor of William James, and chatted with other guests while looking down dizzily on her little house. That was her passing acquaintance.

Gammy may have also played a part in introducing me to her distinguished neighbor. Since the death of her husband in 1949, she had turned down the Harvard trustees’ many offers to purchase 34 Kirkland, even if she would only leave it to them in her will. I suspect that my early admission to Harvard, despite my feeble academic record, was an embellishment to the long overture the trustees dedicated to winning Gammy’s heart and house. I arrived in Cambridge in the fall of 1968 and, aspiring to major in psychology, attended classes in William James Hall. I also tried to decipher, among other books, James’s Principles of Psychology. That was my passing acquaintance.

After a few semesters of Harvard I signed up for a one-year leave of absence and have been absent ever since. But recently I’ve been renewing my acquaintance with a chapter or two of Principles of Psychology. And I’ve been noting that Srila Prabhupada’s writings, * [*His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, founder and spiritual master of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, wrote over fifty volumes of translation and commentary on India’s ancient Vedic literature. Srila Prabhupada’s books contain a wealth of practical information in all fields of knowledge.] which I study daily, illuminate the many obscure corners of the field of psychology, especially shedding light on what James called the “Soul Theory,” or the “orthodox ‘spiritualistic’ theory of scholasticism and of common sense.”

On the first page of Principles James asserts that in psychology, the science of consciousness, there are essentially two ways to account for such things as feelings, desires, and thoughts. The first way is to consider them symptoms of a personal soul that exists separate from the physical body, detached and self-sufficient. The soul has permanent faculties for volition, reasoning, memory, imagination, and so on, and the phenomena of consciousness are manifestations of these faculties. We remember because the soul has recollective power, reason because it has reasoning power. These powers are absolute in the sense that they have no physiological components. They are “irreducible faculties.” This is James’s commonsense spiritualistic theory.

The second way to account for our thoughts and feelings is to say that they are not manifestations of an individual soul at all, but rather the product of certain mechanical laws. These laws influence the elements of consciousness, which are components of our brains and nervous systems, to group themselves in various patterns and forms, thus producing memories, perceptions, desires, and all the other trappings of an individual mind. According to this theory, individual ego is the final product of interactions that take place within the brain. Individual consciousness, in other words, arises from matter—gray matter.

In Chapter Six of Principles, James traces this materialistic perspective back to the theory of evolution, which posits that inorganic compounds appeared first, then lower life-forms, then animals (who possess some consciousness), then human beings (who possess a lot of it). The evolutionists’ premise is that “The selfsame atoms which, chaotically dispersed, made the nebula, now jammed and temporarily caught in peculiar positions, form our brains.”

Evolutionary theory is more or less acceptable, James proposes, as long as it sticks to explaining the arrangement and rearrangement of the elements of material nature. But consciousness, he says, is apparently a completely new nature. Evolution may have produced some highly complex gray matter, but we cannot observe consciousness by poking around in our cerebral cortex.

The most we can say is that certain brain conditions appear to correspond with certain conditions of consciousness. When alcohol goes to a man’s head, for example, it alters his thoughts and feelings. But the exact relation between our brains and our thoughts and feelings is not clear enough for us to assert that consciousness arises from matter. Although James doesn’t categorically reject the materialistic viewpoint, he devotes the sixth chapter to pointing out its flaws.

Reading Principles back in 1968, I found most of this material-spiritual stuff unintelligible. I felt I was surveying familiar ground from an alien place, like Gammy must have felt peering down at her white clapboard home from the summit of William James Hall. Nothing could be more down-home than our own selves, yet from the intellectual heights of Principles, individual consciousness looked to me like a pickled specimen. James had clarified a principle of human psychology that is very close to home for everyone, but it wasn’t until I later read the Bhagavad-gita As It Is that the material-spiritual business came fully into focus.

In the Bhagavad-gita Lord Krsna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead, tells us straight out that we are not our physical bodies but eternal individual souls and that consciousness is the energy of the soul. As sunlight streaming through a window indicates the sun is up, so the consciousness pervading the body indicates the soul’s presence. According to the Gita, thoughts and feelings are indeed manifestations of the soul’s irreducible faculties. Furthermore, our very drive to survive is evidence of the soul’s eternal nature. Krsna thus strongly affirms the spiritualistic theory.

The Gita and other Vedic texts further clarify the difference between matter and spirit by distinguishing, unlike James and many other Western philosophers, between mind and consciousness. Vedic sources explain that while consciousness is the soul’s energy, mind as we now know it is part of a subtle material body situated within our gross, flesh-and-bone body. The soul proper does have faculties of thought, memory, and so on, but these pure faculties are now covered and distorted by the subtle body. The subtle body covers the soul like a shirt and is in turn enveloped by the “coat” of the gross body.

For the purposes of this article, however, we can accept James’s equating of mind and consciousness, since it is a fact that without consciousness neither the subtle nor the gross body can function. Through consciousness the soul energizes both the subtle mind and the gross physical frame. When the soul passes away, it takes the subtle body with it and leaves the flesh and bone lifeless. The immediate source of our thoughts and feelings is the subtle mind, but the original source is the soul.

In addition to confirming and elucidating the soul theory, the Vedic literature forwards powerful arguments against the soulless materialistic perspective. Srila Prabhupada explains: If consciousness arises from matter, then modern scientists, with so many sophisticated laboratory techniques at their disposal, should be able to create consciousness from material elements. They should be able to produce at least a one-celled organism, or to restore life to a dead body. A corpse has all (or most) of the chemicals and other ingredients of a living body. So take all those ingredients, adjust and add to them as you like, and bring the body back to life. Give it consciousness. That’s a tall order, but until we fill it the materialistic theory remains only a theory.

Srila Prabhupada’s “Create consciousness!” challenge brought to life for me James’s allegation that the chasm between matter and consciousness had yet to be bridged by experimental evidence. The challenge made it clear that today, almost a century after the publication of Principles, James’s allegation still carried weight. In recent decades, scientists have synthesized amino acids and combined the human sperm and ovum outside the womb, but they still have not created any life-form, even an amoeba or a flea. They have not and they cannot, because consciousness is not built of material elements. Prabhupada’s simple challenge exposed the weakness of the materialistic perspective, turned me into a spiritualist, and made James intelligible to boot.

Yet James, by his own admission, was not a dedicated follower of the soul theory. He ultimately rejected both the materialistic and spiritualistic perspectives. The fault in the soul theory, James pointed out, is that it fails to explain why consciousness, though it may not be a product of matter, is affected by material conditions. If the soul is part of a different nature, then why does the material nature influence it?

James used memory as an example. Soul theorists say that memory is an absolute faculty, yet we all have practical experience that circumstances can cause our memories to fail us. I know, for instance, that my parents took me to see Gammy at 34 Kirkland Street many times during my childhood, yet I recall most of those visits only vaguely, if at all. On the other hand, one memory I do have—a Christmas visit when I was six—is crystal clear. Cambridge was deep in snow that December. In Gammy’s yard I was up to my waist, and the cold white blanket turned her forsythia hedge into a grand twiggy cavern. I went caroling with my parents and some of my father’s old friends, and on Christmas morning I tiptoed down the narrow spiral staircase to peek at the pile of presents in Gammy’s living room.

Our memories hold on to some things better than others, and this appeared curious to James:

For why should this absolute god-given Faculty retain so much better the events of yesterday than those of last year . . . ? Why, again, in old age should its grasp of childhood’s events seem firmest? Why should illness and exhaustion enfeeble it? . . .Why should drugs, fevers, asphyxia, and excitement resuscitate things long since forgotten?

Here James uses the word “absolute” in a broader sense, to mean not just “without material components” but also “unaffected by material conditions.” Since memory and other faculties of the soul are undoubtedly affected, James felt that the mystery of how this could be so must haunt all spiritualists.

Although he found the soul theory to be the most logical, James concluded that even if there is a soul, all we can directly observe is consciousness, the soul’s energy, and that a psychologist should therefore restrict himself to ascertaining the correspondence between brain conditions and conditions of consciousness. This conclusion, he said, was “the last word of a psychology which contents itself with verifiable laws, and seeks only to be clear, and to avoid unsafe hypotheses.”

It is a tribute to James’s honesty that he admits there is no way he can empirically verify whether the source of individual consciousness is a spiritual soul or a complex pattern of material atoms. But what an admission! William James, perhaps America’s greatest psychologist, one of my grandmother’s neighbors, and a Harvard man at that, didn’t even know who he was. That’s unsettling. By most standards, especially psychological standards, a person uncertain of his very identity is nuts.

In his books, Srila Prabhupada many times explains that this is the predicament of the empiricist: He refuses to rely on anything but his imperfect senses, mind, and intelligence and must therefore forever content himself with imperfect knowledge. Not only can we not conclusively identify our own selves through empirical research, but all our sensual observations are potentially faulty, leading to many “unsafe hypotheses,” even in fields where conclusions are apparently verifiable.

But the solution to the empirical quandary is not to abandon (in the name of honesty) the quest for absolute truth, as James did in Principles. Lord Krsna states in the Bhagavad-gita that the perfection of empiricism, of lifetimes of research, is to understand the Absolute by surrendering to Him, serving Him with devotion, and allowing Him to reveal Himself. Since the Absolute’s senses, mind, and intelligence are perfect and unlimited. His “empirical” knowledge, His observations and experiences, His teachings, are complete and without fault. For the empiricist who at least theoretically accepts Krsna as the Absolute Truth, studying the Gita in that submissive mood, all questions about both matter and spirit are fully answered.

That haunting question, for example: How can matter, or material conditions, affect the absolute, God-given, nonmaterial faculties of the soul?

The answer, simply enough, is that matter and material conditions are also God-given. According to the Gita’s seventh chapter, those “self-same atoms” James talks about, the ones that made the nebula and which now form, among other things, our brains, constitute an energy of the Supreme Lord, His inferior energy. Hydrogen and helium, water and air, bricks and mortar, flesh and bone—all these are “inferior energy” because they lack consciousness and are thus qualitatively different from Lord Krsna in His original, all-cognizant, all-blissful personal form.

Krsna controls all movements of His inferior (material) energy, repeatedly creating and destroying the universe and the varieties of bodies, forms, and conditions we perceive around us. Even man’s creations—his skyscrapers, motor vehicles, institutions, his works of art, his psychological treatises—come about only through God-given energies.

We spirit souls inhabiting material bodies are also an energy of Krsna’s, His superior energy. We are qualitatively equal to Krsna, by nature blissful and full of knowledge. But quantitatively we are not equal. Krsna is infinite, we are infinitesimal. He is the potent, we are the potency. He is the master, and we are all, by our very nature, His servants. The superior energy, too, is fully under Krsna’s control.

But we have a little freedom, a choice. We can serve Krsna directly and willingly, surrendering to His control and enjoying His blissful association, or we can rebel and be forced to serve Him indirectly, through His inferior energy. The Visnu Purana states that we are sparks of Lord Krsna, who is the supreme fire. As long as we remain within the fire, our blissful spiritual qualities blaze freely, but upon leaving the roaring flames we fall to the ground and are almost completely extinguished. The “ground” is the inferior, material energy, which the Visnu Purana calls avidya-sakti, or “ignorance energy,” because it is specifically designed to delude and harass rebellious souls, fulfilling their desire to forget their spiritual identity.

So why do old age, illness, exhaustion, drugs, fever, and a host of other material conditions affect the soul? My old acquaintance, William James, posed this question, and being unable to answer, remained uncertain of the soul’s existence, and thus of his own identity. But the Vedic literature answers decisively that only rebellious souls, those who have deliberately rejected the shelter of matter’s controller, come under matter’s influence. When the soul is in the fire of Krsna consciousness, the inferior energy cannot afflict it.

James’s uncertainty is itself an affliction, a blotch of ignorance brought about by the inferior energy. James wanted proof of the soul, but he didn’t know that surrender to the Supreme Soul is the only way to have it. He also, I assume, in narrowing the science of psychology to a search for the correspondence between material conditions and conditions of consciousness, wanted to find ways to liberate consciousness from the material conditions of old age, disease, and death. That is the topmost achievement for any scientist, the achievement most heralded in human society. But complete liberation from miserable conditions also requires surrender to Krsna. Or, to put it in Jamesian terms, the power of material conditions to subjugate us corresponds to our rejection of Krsna consciousness.

Down-home proof of the Vedic soul theory is available to anyone participating in the Krsna consciousness movement. Krsna assures us, again in the Gita’s seventh chapter, that although overcoming His material energy is difficult, it is easy for those who have surrendered to Him.

So, surrender to Krsna. Learn the science of Krsna consciousness, practice it, and feel the inferior energy’s grasp gradually loosen.

Leave a Reply