A Duty Made Divine

Cooking for Krsna turns “something to get over with” into a pleasure you’ll want to get into.

by Visakha-devi dasi

While browsing through the Cooking section of one of Philadelphia’s largest bookstores, I came across a startling passage in the introduction to a popular vegetarian cookbook: “It hadn’t occurred to me that there could be much direct connection between kitchen work and meditation until one evening when our teacher was reading some verses from Bhagavad-gita, in which Lord Krsna tells His disciple, ‘If one offers Me with love and devotion a leaf, fruit, flower, or water, these I will accept. All that you do as well as all that you eat should be offered unto Me. Thus you will be freed from all reactions to both good and evil deeds, and you will be liberated and come to Me.’

“Our teacher talked all evening about how work without thought of profit is actually a form of prayer,” the book continued. “Even the smallest task can be thought of as an offering to the Lord, and when it is, it follows that it will be performed in the best possible way, with the greatest care and attention. Looked at in this light, every action becomes, potentially, an act of love—a work of art …”

I guess I found this passage startling because after many years the same book—Bhagavad-gita—had brought me to a similar understanding about kitchen “chores.” My mother cooked for my father, my brother, and me only because she felt it was her duty. She thought kitchen work drudgery (she used the then well-known I Hate to Cook Book), so she never encouraged me to cook, but to do things more “creative” and “fulfilling.” I survived college on cafeteria fare and snacks. So the first twenty-seven years of my life I managed to avoid cooking. It wasn’t till I’d been a devotee of Krsna for six years that I entered the kitchen as a cook for the first time.

It was then that it gradually dawned on me that my attitude toward cooking was a combination of Madison Avenue hype, the women’s lib movement, and a profound lack of God consciousness. The ads get across that although eating is a most pleasurable affair—a time of warm family reunion, of intimacy with those we love—preparing food is a drag. After all, everyone knows that you do have much more important things to do, so naturally meals should be as quick and easy to assemble as possible. How can a twentieth-century woman simply stand there cutting a cauliflower, with the Middle East in crisis, millions going hungry, and the national economy tottering? Besides that, what about your undeveloped creative flair, that super-savings sale in the store just fifteen miles away, and last Sunday’s paper lying yet unread? And anyway, after a busy day you’re just a little too tired to cook. So manufacturers, out of their kindness, have produced a vast array of machines to save time and work and prepare food of every description.

As I slowly tried to grasp the principles of Vedic cookery, my mind sometimes went back a few years to a lecture on Bhagavad-gita I’d heard Srila Prabhupada deliver to a crowd of twenty thousand Indians in New Delhi. He’d spoken emphatically, leaning forward in his seat, and raising and lowering his voice as he asked and answered his own questions:

“The businessman says, ‘I have my duty.’ The student says, ‘I have my duty.’ The housewife says, ‘I have my duty.’ But what is your duty, my dear sir, my good woman? Ah, that they do not know. They think of duty towards their boss, their teacher, their family. But these are temporary duties. They come and go with the body. Our real duty is to learn how to love God, to perfect that love and go back home, back to Godhead, at the end of this life. That they do not know.”

I was learning to cook from Yamuna-devi dasi, the expert devotee-cook who has written the recipes we’re presenting each month on these pages. And as her classes went on, they shed a new light on the culture I’d seen for the few years I’d lived in India. There people spend hours sorting and grinding dal, kneading, rolling and cooking unleavened breads, cleaning spices, and drying herbs. There they’ve got no qualms about cooking down a pot of milk for an hour and a half to make milk sweets, and they don’t hesitate to embark on a complicated dish that will take a good part of the morning to complete. So for a devotee, cooking is not something to get over with so I can get on to something really important. Cooking is a way to please Krsna. It is an end in itself.

Generally, for one who’s not a devotee, the pleasure is in the result—eating, and leasing the senses of others. Cooking is something you have to go through to get the result. But for a devotee the end (accepting prasadam, food that’s been offered to Krsna), the beginning (cooking it), and the middle (offering it to Krsna) are all equally relishable, because they’re all devotional service to the Lord.

With this attitude, the Krsna conscious cook in his or her kitchen has a place in spiritual life just as much as the Krsna conscious lecturer on his podium, the Krsna conscious judge on his bench, the Krsna conscious typist, the Krsna conscious writer, and the Krsna conscious businessman. So, I reasoned, if I’m becoming eligible to go back to Godhead by this kitchen work, what’s the big rush to get out of the kitchen to do something else?

Of course, it’s not necessary to bury your blender and spend sunrise to sunset at the stove. All we need is a change in the focus of our cooking, so that we collect the ingredients that Krsna will accept (no meat, fish, or eggs), remember Him as we cook, offer the dishes to Him with love and devotion, and distribute and relish the prasadam to our full satisfaction. It may not seem like much, but the effect is startling, as the vegetarian cookery book I was reading confirmed in the next paragraph:

“You aren’t just slapping together a meal; you’re preparing food for the Lord.”

(Recipes by Yamuna-devi dasi)

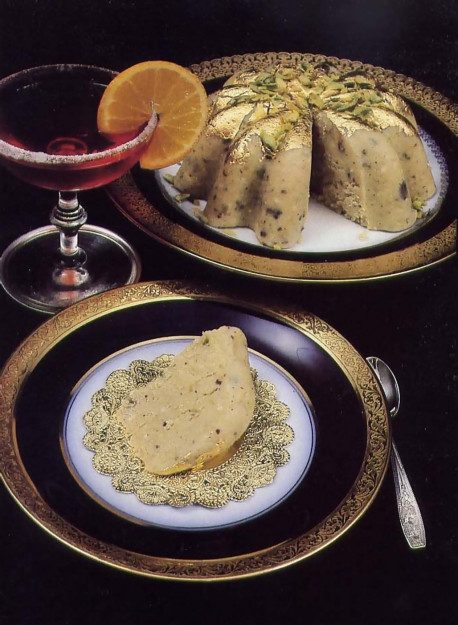

The Grand Milk Cake

Proper equipment will help cut the time you spend stirring this large quantity of milk as it condenses and solidifies. If you have a heavy 8-quart saucepan, that’s the best; otherwise, condense the milk in two phases in a standard 5- or 6-quart saucepan. The finished result is an extraordinarily rich, stately cake with a divine flavor and texture. Cut it in small wedges for serving. Makes a cake about five inches in diameter and three inches high. It is especially respected by those who know the time that goes into the condensing and stirring.

Preparation time: 2 hours

Servings: 6 to 8

12 cups fresh whole milk

1 teaspoon citric acid crystals

1 ¼ cups sugar

½ teaspoon cardamom seeds, crushed to a powder a buttered stainless-steel bowl 4 inches to 5 inches in diameter or a 2 ½-cup decorative mold

1 or 2 sheets edible gold or silver decorative foil, if available

1 tablespoon blanched, raw pistachio nuts, sliced fine

1. Condense the milk by following either procedure A or B:

(A) Pour all the milk into a heavy 8-quart saucepan (nonstick cookware is ideal) and place it over a high flame. Stirring constantly with a wide wooden spatula, bring the milk to a full boil. Stir and boil the milk vigorously until it comes down to about 6 cups.

(B) Pour 6 cups of the milk into a heavy 5- or 6-quart saucepan and place it over a high flame. Stirring constantly with a wide wooden spatula, bring the milk to a full boil. Stir and boil the milk vigorously until it comes down to 3 cups. Put aside the 3 cups of condensed milk. Pour the remaining 6 cups of milk into the saucepan and cook until it comes down to about 3 cups. Pour in the other 3 cups of condensed milk.

2. Place the condensed milk over a moderate to medium-high flame and boil while stirring constantly. Very slowly, at about 3-minute intervals, sprinkle in dry, separate crystals of citric acid, adding from 1/8 to 1/3 teaspoon at a time until small granules form in the milk. If the grains of citric acid fall into the milk in clumps or become moist and stick together, there is every chance that undesirable small lumps of cheese will form. Continue to stir, boil, and condense the milk until it reaches the consistency of heavy cream. Then reduce the flame to medium to prevent the bottom of the pan from scorching.

3. Add the sugar, and while stirring rhythmically, methodically, and vigorously, condense the milk until it becomes a thick paste. Regulate the flame so that you can condense the milk as quickly as possible without scorching or burning it. When the milk is somewhat dry and almost thick enough to pull into a mass, remove the pan from the flame and pour the milk into the buttered bowl or mold. Cover securely. Allow the preparation to sit for about 12 hours.

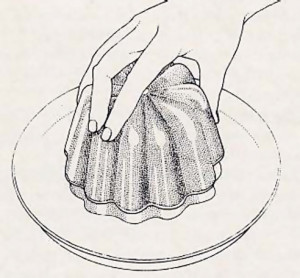

4. To remove the cake from the mold, first loosen the cake by partially submerging the mold in a container of boiling water. Then gently run a spatula or butter knife down the walls of the mold. Now invert the cake onto a small decorative serving tray or platter.

5. Garnish the surface of the cake with edible gold or silver foil or a sprinkle of slivered pistachio nuts. Cut the cake into small delicate wedges before offering to Krsna.

Creme de la Creme (Rabri)

This creamy, moist milk dish is always served chilled. Whether taken as is or mixed with diced fruits such as ripe mangoes, papayas, or bananas, it is served in individual shallow bowls or cups. It may be sipped or eaten with a spoon.

Preparation time: 1 ½ hours

Servings: 4 or 5

4 cups fresh whole milk

3 to 4 tablespoons sugar or mild-flavored, light-colored honey

¼ teaspoon whole cardamom seeds, slightly crushed

3 to 4 drops of kewra essence or 1 tablespoon rosewater, if available

1 ½ tablespoons blanched raw almonds, sliced into paper-thin round slivers for garnishing

Equipment:

10-inch to 14-inch karhai or wok (bowl-shaped pan)

large wooden stirring spoon

another wooden spoon

8-inch by 10-inch piece of heavy cardboard to use as a fan

1. Pour the milk into a clean bowl-shaped pan and place it over a high flame. While stirring the milk constantly, bring it to a full boil. Boil briskly for about five minutes.

2. Reduce the flame to medium, and, without stirring, allow the milk to boil gently. While fanning the surface of the milk with the left hand, pull a wooden spoon across the surface to collect the thin “skins” of cream that form from time to time. Pull them up the side of the pan above the surface of the milk and collect them all around the top sloping edges of the pan. Stir the bottom of the pan occassionally to keep the milk from sticking. As the milk condenses, the stirring is more frequent. Continue fanning and collecting the “skins” of cream until only about ¼ of the milk remains. Add the sweetener and cardamom seeds and let the milk simmer for about 4 or 5 minutes more.

3. Remove the pan from the heat, cool, and scrape all the layers of cream from the sides of the pan into the sweetened condensed milk. Mix well. Cool the mixture to room temperature, stir in the essences, and refrigerate until cold. Before offering to Krsna, garnish the servings with sprinkles of almonds and pistachios.

Leave a Reply