An Indian Saint in America

A scholar’s portrait of the founder and spiritual guide of the Hare Krsna movement.

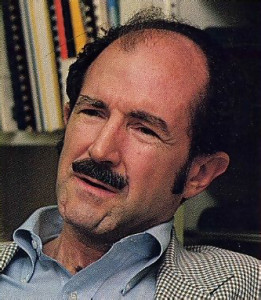

Professor Thomas J. Hopkins is chairman of the department of religious studies at Franklin and Marshall College, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. A noted scholar of Hinduism, he is the author of The Hindu Religious Tradition, a standard college text. His special interest in bhakti (devotional) Hinduism led him, in 1967, to encounter the recently established Krsna consciousness movement and its founder, His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, and Dr. Hopkins became the first serious academic observer of the movement.

Professor Thomas J. Hopkins is chairman of the department of religious studies at Franklin and Marshall College, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. A noted scholar of Hinduism, he is the author of The Hindu Religious Tradition, a standard college text. His special interest in bhakti (devotional) Hinduism led him, in 1967, to encounter the recently established Krsna consciousness movement and its founder, His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, and Dr. Hopkins became the first serious academic observer of the movement.

In the following excerpt from an interview, Dr. Hopkins reflects upon Srila Prabhupada’s stature as spiritual leader, saint, and scholar. The full interview appears in Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna: Five Distinguished Scholars on the Krishna Movement in the West, a book recently published by Grove Press (paper, $7.95). The interviewer and the book’s editor is Steven J. Gelberg, ISKCON’s Director for Interreligious Affairs, who is known within the Hare Krsna movement as Subhananda dasa.

Reprinted by permission of Grove Press, Inc. Copyright 1983 by Steven Gelberg

Subhananda dasa: Perhaps you could say something about the historical importance of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s [Srila Prabhupada’s] bringing of the message of Krsna consciousness to the West.

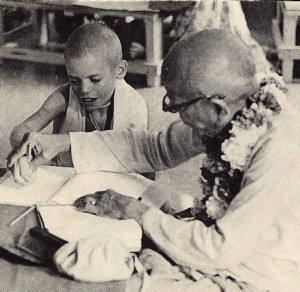

Thomas Hopkins: Bhaktivedanta Swami was the inheritor of a revitalized Caitanyaite tradition [The Caitanyaite tradition, or the Gaudiya Vaisnava tradition, was founded by Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu, who is Lord Krsna Himself taking the role of His own devotee. He appeared in Bengal, India, five hundred years ago and taught love of God through the congregational chanting of the Hare Krsna mantra.] as it came down from Bhaktivinoda and Bhaktisiddhanta. Let’s backtrack a bit and take a quick look at his life in India before coming to the United States. He was born in Calcutta in 1896 and received an English education at Scottish Churches’ College in Calcutta. After college he went into business and ran a pharmacy for many years in Allahabad. After his initiation in Allahabad by Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, he turned his attention increasingly to the religious duty set by his teacher: to preach the message of Caitanya to English-speaking people.

Thomas Hopkins: Bhaktivedanta Swami was the inheritor of a revitalized Caitanyaite tradition [The Caitanyaite tradition, or the Gaudiya Vaisnava tradition, was founded by Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu, who is Lord Krsna Himself taking the role of His own devotee. He appeared in Bengal, India, five hundred years ago and taught love of God through the congregational chanting of the Hare Krsna mantra.] as it came down from Bhaktivinoda and Bhaktisiddhanta. Let’s backtrack a bit and take a quick look at his life in India before coming to the United States. He was born in Calcutta in 1896 and received an English education at Scottish Churches’ College in Calcutta. After college he went into business and ran a pharmacy for many years in Allahabad. After his initiation in Allahabad by Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, he turned his attention increasingly to the religious duty set by his teacher: to preach the message of Caitanya to English-speaking people.

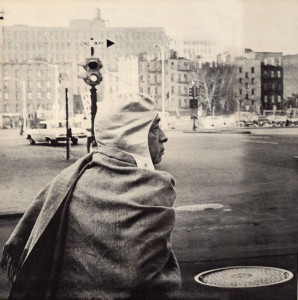

He founded the magazine BACK TO GODHEAD in 1944 to serve as a vehicle for this purpose and produced a series of English expositions of sacred writings. His long-term goal, however, was a translation and commentary on the Bhagavata Purana [Srimad-Bhagavatam]. He began work on this project after being initiated into the renounced order, sannyasa, in 1959, and by 1965 he had completed and published the First Canto of the Bhagavata in three volumes. At that point, armed with a message and a mission, he set sail for New York City to bring Krsna consciousness to the West.

Bhaktivedanta Swami’s success story is an unlikely one, to say the least. He was seventy years old when he arrived in America. It was his first trip outside India; he had no money and no local means of support. But he did have a revitalized and spiritually rich Gaudiya Vaisnava tradition that had been imbued, by both Bhaktivinoda and Bhaktisiddhanta, with a spirit of universality and of relevance to the modern world. But it must be admitted, certainly, that not just anybody could have inherited and transmitted that legacy. Other disciples of Bhaktisiddhanta had tried and failed to bring the devotional message of Caitanya to the Western world.

And after Bhaktisiddhanta passed away, his organization, the Gaudiya Matha, was torn asunder by internal power struggles and other kinds of upheaval. Bhaktivedanta Swami, obviously, was a very special person, a spiritual leader of rare power. His success in bringing the message to the West and planting it in a place where it took root and flourished without compromising his tradition has to be seen as largely an effect of his tremendous personal spirituality and holiness and his incredible determination.

It’s an astonishing story. If someone told you a story like this, you wouldn’t believe it. Here’s this person, he’s seventy years old, he’s going to a country where he’s never been before, he doesn’t know anybody there, he has no money, he has no contacts. He has none of the things, you would say, that make for success. He’s going to recruit people not on any systematic basis but just by picking up whomever he comes across, and he’s going to give them responsibility for organizing a worldwide movement. You’d say, “What kind of program is that?”

There are precedents, perhaps. Jesus of Nazareth went around saying, “Come follow me. Drop your nets, or leave your tax collecting, and come with me and be my disciple.” But in his case, he wasn’t an old man in a strange society dealing with people whose backgrounds were totally different from his own. He was dealing with his own community. Bhaktivedanta Swami’s achievement, then, must be seen as unique.

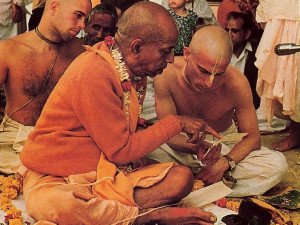

Bhaktivedanta Swami’s personal example of devotion was not only impressive, but it was compelling, as evidenced by the way in which so many young Westerners were drawn to him. What got people chanting the Hare Krsna mantra in the beginning was confronting Bhaktivedanta Swami and being just overwhelmed by the man and feeling, “I want to be near this person; I want to become like this person.” And his approach was one of taking people on and saying, “Here’s how.”

I don’t think any devotional tradition has ever really been successful without some kind of model devotee to provide an example of devotion and of holiness. The role of the holy man is really inseparable from the devotional traditions. There’s just no way you can convey the quality of devotion without an example of devotion. Devotion, in the sense of spontaneous devotion, is not something you can teach people intellectually or convey by reciting a set of abstract principles, saying, “Now, being devotional means being such and such. Number one you do this and number two you do that.”

Of course, devotion does not arise out of nowhere. The devotional path is indeed a path. The devotee follows various religious regulations and disciplines that gradually revive the natural devotion of the soul, of the heart. But it is difficult to adhere to such disciplines, or to know how to adhere to them, if there is no good example of a devotee to follow. The devotional tradition makes this point constantly: association with saints inspires saintliness, association with devotees inspires devotion. The association of genuine devotees can exert a powerful effect upon one’s consciousness.

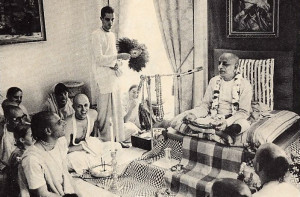

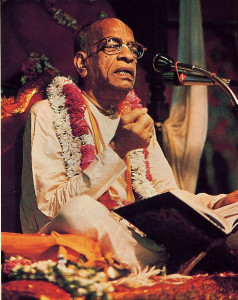

I can clearly remember the quality of Bhaktivedanta Swami. He wasn’t a great singer in the sense of having a superstar’s recording voice; his was the voice of a man seventy years old. Yet when he chanted and when he sang, the whole enterprise took on a different quality, and he would shape the experience for other people. You could see him shaping the experience for other people. If the chanting became routine, if it began to lose its spirit, he would change the beat, change the meter, or introduce some new element into the kirtana to bring people’s minds back to what they were doing.

So you could see him very consciously and very patiently shaping people’s devotional practices and their sense of who they were, and bringing them to the standard. He would guide people not by saying “That’s wrong” or “We don’t do it that way in India” but by providing, as people became ready, new examples and new levels of attainment so that one never reached the end of the process. There was always another level to reach. No one ever seriously expected to reach his level, and yet he never set that level so far beyond where people were that they would view it as unattainable. He was a master at making that kind of contact.

Bhaktivedanta Swami was certainly one of those people who had that capacity to guide and direct and to discipline. He wasn’t afraid to set standards. Regarding his effectiveness in dealing with counterculture youths, from the very beginning it seemed to me to be obvious that he was providing a sense of direction to people to whom no one had ever really given that kind of guidance. Their parents and other authority figures had simply told them, “Do whatever you want. It’s your life; go out and do whatever you want with it.” That’s not much to go by. Bhaktivedanta Swami’s approach was quite different. If you wanted to live your life the way you wanted to live it, that was all right with him, but not where he was!—and not in the temple and not in the community of disciples. In the temple there were standards, and there was a wise, compassionate, and understanding person who knew what was what. There was never any question of where he stood on things. He never pulled any punches or watered down his position to lull people into submission or acceptance.

Subhananda dasa: The concept of submission to a spiritual master is, of course, very deeply rooted in Eastern spiritual traditions. But in the West there’s a very strong distrust of the very idea of guru—a spiritual authority to whom one submits oneself for spiritual guidance. The typical Western response is to view that kind of submission as a sort of abandonment of rational, critical thought and of personal autonomy. How is it, then, that Bhaktivedanta Swami’s young disciples were able to transcend the Western apprehension about absolute spiritual authorities and accept his authority as a spiritual master?

Dr. Hopkins: I think it’s partly because that fear of submitting oneself to an authority is not really fear of submission to authority per se. Rather, it’s a fear of being taken, of submitting to a false authority or a deficient authority. All three of the major American religious traditions have some emphasis on the notion of submission to authority. Roman Catholic tradition involves submission to the ultimate authority of the pope, and to the priest as an immediate authority. The Jew makes his submission to the Law, and to the rabbi who interprets and speaks for the Law. In the Hassidic tradition, one makes submission to the rebbe, who certainly is a respected spiritual authority—no question about it. He has authority and he enforces discipline. In the Protestant tradition, you have submission to the word of God, the Bible. The idea of submission is certainly not absent in the Western religious tradition.

What I think most of the young people in the counterculture were rebelling against was the fact that authority had let them down. Authority was not doing its job, as it were. Their parents were saying one thing and doing something else. The government was saying one thing and. Lord knows, doing all sorts of other things. The principles of democracy were being contradicted by what was happening in American society. If there’s anything that Americans—especially—are afraid of, it’s being taken. If there’s anything that bothers an American, it’s being sold a bill of goods. And when you find out that every authority figure in your life has sold you a bill of goods, you begin to question the whole idea of authority.

But even though many young people in the counterculture might have viewed themselves as rejecting authority per se, in fact they were rejecting false or imperfect authority. When they finally found somebody who had a kind of authoritative quality and who could be trusted, their attitude towards authority changed. Bhaktivedanta Swami came across to them as someone who really did live the way he said you ought to live and who really did follow the standards he said were the standards to follow. And he did so in a way that was not just up to par but was beyond par. The actual quality of his life tended to alleviate their distrust and rejection of authority.

I feel that many adults made a mistake by taking the counterculture youth at their own word when they said they wanted no authority, direction, or discipline. Bhaktivedanta Swami never made the mistake of taking that seriously; he never catered to that spoken statement. He always saw what people really needed and spoke to that.

Subhananda dasa: Unlike Bhaktivedanta Swami, most people who have come to the West in the role of spiritual mentors have tended to demand very little from their followers in the way of submission and obedience, and to set very low standards of personal conduct and discipline. Their attitude toward the personal morals of their disciples is generally laissez faire—as it often is toward their own personal morals. Very few, for instance, have even attempted to set up or enforce strict rules encouraging sexual restraint or abstention from intoxicants (as is considered important in most of the traditions and disciplines these teachers represent). Why is it, then, that Bhaktivedanta Swami was able to demand, and receive, from his students a high standard of personal conduct and spiritual discipline?

Dr. Hopkins: I think what he did was simply to say, “Okay, here is something of value, and here’s what you have to do to get it.” And, what he offered was genuine and sufficiently attractive so that people were prepared to pay the price. Many of his students had previously sought spiritual life elsewhere and had been disappointed—especially with the form of religion handed to them by their nominally Christian or Jewish parents. I had a number of conversations with devotees about their home synagogues, for instance, in which they described surrealistic encounters with their rabbis. When they tried to raise the question of spiritual life and spiritual experience, they got only blank stares and responses like, “What is that? We don’t do that here.” So they didn’t feel that they were getting much from their rabbis. When they finally found someone who offered them tangible spiritual life, they were prepared to pay the price to receive it. For most people, those who were serious, the price wasn’t too high to pay.

There were, and there probably still are, a lot of people who always were disciples on the outside—friends of the movement, interested participants—but who were never willing to make the movement to discipleship for one reason or another. For many people, the demand of discipleship was more than they could meet. But everyone I met was respectful of that demand and viewed the problem not in terms of what was demanded but in terms of his or her inability to meet the demand.

Subhananda dasa: From what you observed during your various visits to the temple in New York in its early days, is there anything you remember in particular about Bhaktivedanta Swami’s dealings with his disciples? Anything which particularly stands out in your mind?

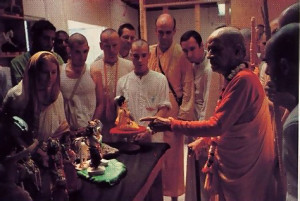

Dr. Hopkins: The one thing that I remember, the thing that I am constantly struck with, was the total confidence with which Bhaktivedanta Swami had people doing things. Take the example of his disciple Brahmananda. Bhaktivedanta told him, “Go and start a magazine. Start a printing and publishing enterprise.” And Brahmananda replied, “I don’t know how to do it.” And Bhaktivedanta said, “Well, find out. Krsna will help you.” This sort of exchange occurred numerous times, with numerous disciples. He inspired a sense of confidence in people because he himself was absolutely confident and convinced. He had no doubt that what he told people to do they would be able to do. He had much more confidence in people than they had in themselves, to say the least.

His confidence, however, was not in others or in himself exactly, but in Krsna. That’s the other thing that was so impressive about the man himself. He never put himself forward as having the power to make things happen. He never said, “Go and do this because I will give you the power. I will inspire you to do great things.” He always said, “Krsna will give you the power. Krsna will guide you.” It was a confidence not in himself or in the other person but in Krsna, and that was effective. He wouldn’t have been so effective, I think, if he had said, “You’ve got to have confidence in yourself,” because that’s pretty hard to do if you don’t have confidence in yourself; nor if he had said, “Have confidence in me,” which, although better, you don’t quite know how that works. But, on the other hand, “Have confidence in the Lord of the Universe”—well, that’s a different matter.

Bhaktivedanta Swami’s success as a religious leader of the institutional kind, as distinct from a religious leader removed from any institutional context, lies largely in his ability to engage people in religious activities of a practical nature or, conversely, practical activities with a religious purpose. This is one of the strengths of the whole bhakti tradition. It has tended not to become otherworldly in the sense in which the term is very often taken: utter indifference to the world and to action within the world—reclusiveness, inactivity.

The Bhagavad-gita is really one of the great theoretical and practical statements on how to resolve the conflict between spirituality and materiality. The Hindu tradition in general has managed to combine the religious and otherworldly concern for salvation and release from the world, with the need to perform worldly action. The Gita is one of the great solutions. What Bhaktivedanta Swami did was to take that theoretical solution and apply it practically within a religious institution in a way that most other movements or traditions have not tried to do or have not been able to do. To help people discover what their own nature is, what their own psychological proclivities are, what their natural abilities are, and then to put them to work in some kind of practical way, and to show them how to perform those activities with devotion to God—this is what the devotional tradition is all about.

Bhaktivedanta Swami never tried to construe the teachings of the Gita to encourage some kind of otherworldly religiosity. His teachings were always in practical terms: one can worship Krsna by starting a magazine, one can worship Krsna by producing devotional art, or by cleaning the temple, or by cooking a feast for public distribution, or by repairing the temple car. It is activity performed as devotional service to Krsna that is the practical essence of the devotional tradition and that releases enormous amounts of energy once you get over the hurdle of thinking, “How can I do this?”

Subhananda dasa: Could you say something about Bhaktivedanta Swami’s attention not only to devotional practice but also to the philosophical and theological foundations of devotional practice—the balance between devotion and scholarship?

Dr. Hopkins: One of the things that originally attracted me to the Hindu tradition, and to the devotional movements in particular, was that they never did separate the devotional life from the intellectual life.

One of the things that is most striking about the Bhagavata Purana, for instance, is not just the quality of its devotional statements but also the rigor of its thought. It is not just a kind of romantic devotionalism devoid of intellectual content. It’s a very systematically conceived, very scholarly statement of the devotional life. That combination of emotion and intellect, which has been so often separated in religious traditions, is very consistently kept together in the devotional movement.

Many traditions lack this balance. Take, for instance, Sankara and his intellectually powerful Advaita philosophical tradition. There you have a very strong intellectual tradition but almost no concern for the development of spiritual emotion. On the other side, you have certain Christian, especially Protestant, movements—charismatic or pentacostal movements—which have tremendous emotional engagement but very little attention to the life of the intellect. The Vaisnava devotional movement, on the other hand, has always kept these two things together.

The best example I can think of is Caitanya and His followers the six Gosvamis. Caitanya was the devotee par excellence. His biographers describe the incredible intensity of His devotion to Krsna, His dancing and chanting in spiritual ecstasy. His visions, His deep mystical raptures. Yet He also traveled throughout India and debated—successfully—with some of the leading religious intellectuals of His day, and He also held long discourses on devotional theology with certain followers, including Rupa Gosvami, Sanatana Gosvami, and Ramananda Raya.

The six Gosvamis themselves were great devotees of Krsna and great mystics in their own right, yet simultaneously they were tremendous intellects. They collectively wrote a great number of theologically and philosophically sophisticated texts on bhakti [theistic devotion], among which are some of India’s greatest spiritual classics, such as Rupa Gosvami’s Bhakti-rasamrta-sindhu. Jiva Gosvami was probably the greatest devotional philosopher among them, and his contribution is acknowledged universally.

The intellectual and theological achievement of the Gosvamis was to give a rational, intellectual structure to spiritual emotion. Their writings systematically analyze the different stages of the devotional path, such as vaidhi and raganuga, and the various levels and nuances of spiritual devotion and devotional ecstasy—the various rasas and bhavas and so forth. They gave these things meaning within a broad intellectual and theological context, rooted both in the popular and the classical traditions. There is an intellectual integrity and rational structure to the practice of bhakti. It’s not just a gut, emotional thing. It’s mind and emotion together in a spiritual context. Historically, the real power of the Vaisnava devotional tradition has been in its refusal to separate the intellect and the emotions.

If you look at the points at which any religious tradition is really powerful, they are usually those points at which these various elements have been kept together. If you look at the lives of the great Hassidic rebbes, for instance, you see that they were people of intellect and spirituality, and also practical wisdom. They didn’t separate these different elements. Also look at the greater saints of the Roman Catholic tradition, someone like St. Theresa. She was certainly a great mystic, certainly a person of deep spiritual emotion, but she was one hell of an organizer! She put together an entire monastic order, with its own complete institutional structure. She knew not only how to pray to God, but also how to keep books—and she didn’t see any conflict between them.

This is the quality that certainly came across with Bhaktivedanta Swami. I was in a conversation with him one time where he was really doing all of those things at once: he was giving a disciple some practical instruction in the devotional life, he was explaining some devotional point and summoning up a philosophical explanation for the devotional life, and at the same time he was explaining to someone how to keep tax records straight. And those were not contradictory things; they were all part of the same devotional process.

Any movement or any tradition that loses hold of one of those strands is going to have difficulty. And if it loses hold of more than one, it’s in real trouble. It becomes rudderless, free-floating. If the tradition becomes exclusively intellectual, then you lose a whole sense of emotional life and practical action. If you’re strictly devotional, you lose a sense of the coherent meaning of what you’re doing, and it becomes an emotional trip forever. And if you’re strictly practical, you lose a sense of what it’s all about in terms of inner meaning.

Subhananda dasa: While we’re on the subject of integrating devotion and intellect, perhaps you could say something about Bhaktivedanta Swami’s own literary and scholastic contributions, particularly in the form of his many writings—translations, commentaries, and summary studies on the important texts of the tradition.

Dr. Hopkins: As far as his scholastic and literary work is concerned, the first point that should be made is that he has made certain important texts of the Indian devotional tradition accessible to the Western world that simply were not very accessible formerly. This is very significant. What few English translations there were of the Bhagavata Purana and the Caitanya-caritamrta were barely adequate and were very hard to get hold of. When I was working on my doctoral dissertation and wanted to get hold of a copy of the Bhagavata Purana, the only place where I could obtain a copy of the text and translation was from Harvard’s Widener Library. I had to borrow it from interlibrary loan and have a microfilm copy made of it. Nowadays, if you want to take an airplane trip anywhere, you go to the airport and there’s somebody trying to sell you a copy of the Bhagavata Purana. Bhaktivedanta Swami has really made these and other major texts of the Vaisnava tradition accessible in a way that they never were before, and so he’s made the tradition itself accessible to the West. This is an important achievement.

Subhananda dasa: You say that he made Vaisnava tradition accessible through his books. In what way did he do that? What I mean to ask is, to what degree do you see him presenting the tradition verbatim, as it were, and to what degree do you see him interpreting the tradition, in the sense of updating or modernizing it?

Dr. Hopkins: He has done both. He has been very loyal to the tradition, yet he has communicated the tradition in terms that are comprehensible to a contemporary Westerner. As far as fidelity to tradition is concerned, Bhaktivedanta Swami’s commentaries are very traditional. His commentaries very closely follow those of the important Vaisnava commentators, and the Gaudiya Vaisnava commentators in particular. His commmentry on the Bhagavad-gita, for instance, is based largely on the Gita commentary of Baladeva Vidyabhusana, to whom he dedicates his work. His commentary on the Bhagavata Purana relies heavily upon several major commentaries, such as those of Sridhara Svami, Visvanatha Cakravarti Thakura, and Jiva Gosvami, all of whom he quotes and cites frequently. His commentary on Caitanya-caritamrta is based on the Bengali commentaries of Bhaktivinoda Thakura and Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati. This is something that needs to be stressed, because unless you know the tradition you won’t realize the extent to which he’s representing it. What you’re getting in Bhaktivedanta Swami’s commentaries is a lot more than what appears: you’re gaining access to the whole classic tradition of Vaisnava scriptural commentary. It’s clear that Bhaktivedanta Swami is not commenting on these texts off the top of his head. He’s very strongly rooted in the Vaisnava tradition.

On the other hand, in the tradition of great commentaries, he takes the tradition one step further in application. When you’re writing a commentary, of course, you don’t just start off and do your own thing. You follow the tradition and you bring the text into the present, but you don’t really give a new interpretation to it. There are commentaries which may attempt—and I suppose every commentary in some sense always attempts—a new interpretation, subtly or not. But the main purpose of the commentary is not to give a new interpretation but to give a new application of the teaching, so that you have the same teaching applied to a new audience—an audience that may not have access to the original or earlier commentaries. It’s putting the teaching into a new social, intellectual, and linguistic context so that it becomes as accessible now as the previous commentaries were in their time. A good commentary brings the text into the present. It’s classically been the purpose of commentaries to take the text and to give it meaning in terms of people’s lives so that they’re not just dealing with mere intellectual statements. Writing a commentary is not a merely intellectual or academic exercise—it has a practical goal: to engage people with a living spiritual tradition.

Subhananda dasa: In this light, then, what is significant about Bhaktivedanta Swami’s commentaries?

Dr. Hopkins: What is significant is that his commentaries are the first that have been written specifically for the comprehension of the Westerners and to others not familiar with the total Indian cultural and theological context. If you try to read the commentaries of Jiva Gosvami or Sanatana Gosvami or any of the other great teachers, you find that you have to know quite a bit in order to read them with understanding. They contain a good deal of technical terminology, and they were written with the assumption that the reader was familiar with traditional Indian philosophy, culture, and aesthetics. Anyone who doesn’t come out of that particular cultural background is going to miss at least half of what’s being said.

Bhaktivedanta Swami has managed, successfully, to bridge an enormous cultural gap and to give practical application to teachings that were originally designed for people in a very different cultural setting. That’s not easy to do, by any means. I think he’s been very successful. The very existence of a genuine Vaisnava movement in the West is compelling evidence of his success as a commentator.

Leave a Reply