The shattered life of an American poet impels a young man to search for a way to make his own life whole.

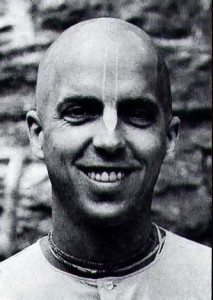

By Tattva-Vit Dasa

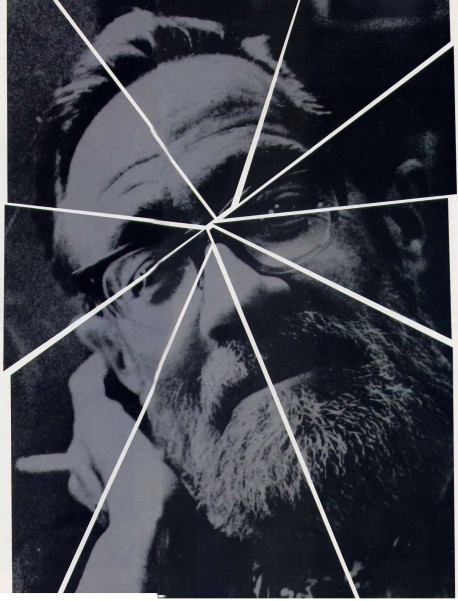

The poet John Berryman was my teacher at the University of Minnesota the year he jumped from a bridge over the Mississippi and killed himself at the age of fifty-seven. In some respects, his suicide puzzled me. He’d won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for his long poem The Dream Songs, and he appeared to enjoy his fame and money. We admired our intense Professor Berryman, who would sit, always well dressed, at the head of our seminar table in Ford Hall, chain smoking Pall Malls while he lectured with candor and erudition on the American character. But his personal life was a mess. He’d been through adultery, alcoholism, and two divorces, and for all his achievements he considered his life misspent.

I felt shocked by Berryman’s suicide, the climax of his abandonment to self-destructive impulses. Along with his various vices, he cultivated a sensibility of insolence toward God, to which he freely admitted in his final poems:

I’m not a good man, I won’t ever be, . . .

his great commands have reached me here—to love

my enemy as I love me—which is quite out of the question!

and worse still, to love You with my whole mind—

It surprised me that poetry, scholarship, and literary acclaim hadn’t made Berryman feel his life was significant. He rejected his unfortunate life on an overcast January day, and his smashed body was recovered near the. west bank of the icy river.

I wondered if I would end up like him. Both of us were lapsed Catholics, both immersed in academic pursuits. I was planning a scholarly career, and Berryman had generously supported my application to graduate school. Now, with his suicide, I had second thoughts.

I belonged to an anti-establishment generation whose quest for peace and pleasure in a youthful counterculture failed as sex, drugs, and alcohol obliterated our ideals. I came to my senses about the time that billboards appeared in Minnesota informing everyone that venereal disease was at an all-time high. Then Minnesota legalized abortion.

My reaction to Berryman’s death, and to the social chaos I saw around me, was to look inward. I decided that if I wanted to become wise and truly human, I needed to take up some form of spiritual life. So I gave up my plans for graduate school and started searching.

I examined The Dream Songs for a sense of direction. Despite the dreary bitterness in which Berryman’s life ended, I knew that his conscience had been unappeasable. Some of his poems agonize over the modern American delusion that we’ve achieved civilization as we try to become happy in a world in which God seems absent. Berryman saw appetites gone wild, people without any sense of higher purpose, and an amoral society unwilling to foresee the results of its own nasty behavior. Berryman saw America headed for a dead end, exemplified by racial conflict and the Vietnam War:

So now we see where we are, which is all-over

we’re nowhere, son, and suffering we know it,

rapt in delusion, . . .

Berryman had searched for the meaning of life in art. He wrote, “All the way through my work is a tendency to regard the individual soul under stress. … I don’t know what the issue is, or how it is to be resolved—the issue of our common human life, . . . but I do think that one way to approach it, by the means of art, … is by investigating the individual human soul.”

But his art, “coming out of Homer and Virgil and down through Yeats and Eliot,” proved of little use to him. He’d lost faith in the spiritual order of the universe. “My father’s suicide when I was twelve blew out my most bright candle faith, and look at me.”

My own inherited faith resurfaced, however, and I began to broaden my spiritual search by turning back to Catholicism. I considered entering the priesthood. A matronly librarian named Mrs. Peterson, who’d taught me French in high school, advised that if I were going to become a priest I’d better be a good one. We both knew that some priests married or had drinking problems. I even knew of mini-skirted nuns who were developing the knack for social drinking. Mrs. Peterson’s warning struck home. I deeply dreaded being a pseudo-renunciant—one who enters the priesthood and then commits abominations.

Moreover, I had no faith that Catholicism could give me the strength to lead a good life. In Catholicism you go to a priest to confess your sins and you do your penance, but then you go out and commit the same sins again—only to return for another confession. From practical experience I knew that repeated sinning and atonement hadn’t purified my heart of sinful desires. The new goodness, after a certain point, had no longer canceled the previous evil, and eventually I’d given up the charade of atonement entirely.

Berryman had had his own peculiar style of atonement. I was in the Newman Center bookstore one evening and purchased a copy of his Sonnets, a book about adultery that raises the question of “whether wickedness was soluble in art.” Berryman thought so, and he apparently tried to counteract his immorality with artistic merit. But that didn’t make his life more tolerable: “At fifty-five half-famous & effective, I still feel rotten about myself.”

Having found both Berryman and Catholicism lacking, I now turned to the philosophies of the East. I’d studied Asian religions ever since leaving the Church, and now I delved into a serious investigation of yoga. I learned that yoga aims at controlling the sensual urges and liberating the spiritual soul from repeated material lives beset by the miseries of birth, old age, disease, and death.

Eventually I found that I had some things in common with the Hare Krsna devotees, who arrived one day on campus distributing free food and literature. They were practicing bhakti-yoga, they said, the yoga of linking with God through devotional service, and they demonstrated an admirable freedom from materialism. They didn’t eat meat, fish, or eggs, and they refrained from intoxicants, including even coffee, tea, and cigarettes. They didn’t gamble or have free sex. They lived the Vedic principle that the purpose of life is to surrender to God and realize our eternal relationship with Him. Here, it seemed, was a practical form of spiritual life that really could purify the heart. I started discussing the Krsna conscious philosophy with the devotees and reading Bhagavad-gita As It Is, by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada.

Bhagavad-gita means “the Song of God.” It’s Krsna’s song—God’s own instructions on the science of self-realization. From reading Bhagavad-gita and talking to the Hare Krsna devotees, I soon learned the basics of bhakti-yoga. I learned that the name Krsna means “all-attractive” and tells us that God possesses in full all the attractive qualities we have in minute degree: beauty, knowledge, strength, wealth, fame, and renunciation. By definition, no one’s qualities equal or excel Krsna’s, for no one is equal to or greater than God.

I found the personal conception of God taught in Krsna consciousness to be a revelation. Up till then I’d more or less accepted the idea of God taught by Catholics, who understand that He is omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent but that’s about all. Their understanding of God comes down to something abstract. For them. God has no concretely personal qualities: He’s a formless being. Therefore, Catholics have no conception of engaging their senses in satisfying the senses of the Supreme Lord. Of course, priests and nuns renounce the satisfaction of their own senses (at least ostensibly) for “the greater glory of God,” but Catholic laymen, like everyone else, want to satisfy their senses, and they pray to God to fulfill their desires.

Studying with the Hare Krsna devotees, I found it easy to see that because we are all people with forms, God must also be a person with form. But not a perishable, material form like ours. In other words, God has an eternal, spiritual body with eternal, spiritual senses. Unfortunately, because we are frustrated with our temporary, limited, troublesome bodies, we think that for God to be eternal, unlimited, and free from misery He must be formless. But Krsna proclaims in the Bhagavad-gita that while He has a form, that form is fundamentally different from ours. While our body is painfully mortal and full of ignorance and misery, Krsna’s is eternal, full of infinite knowledge and bliss.

Srila Prabhupada states in his commentary on Bhagavad-gita that we shouldn’t expect Krsna to satisfy our senses but should try to satisfy His. Then we will automatically feel satisfied. Since Krsna is the root of all existence, the Soul of our souls, satisfying Him through loving devotional service brings a spiritual satisfaction—a true self-satisfaction—far more complete than the flickering satisfaction of the physical senses. Thus a devotee of Krsna neither renounces sense activity nor tries to enjoy sense pleasure. Rather, he uses his senses to serve Krsna and thus achieves transcendental bliss and detachment from matter. In the Bhagavad-gita (5.21) Krsna describes the perfection of devotional yoga: “A liberated person is not attracted to material sense pleasure, but is always in transcendental consciousness, enjoying the pleasure within. In this way the self-realized person enjoys unlimited happiness, for he concentrates on the Supreme.”

The Catholic doctrine offered an abstract idea of a formless God and no way to transcend material desires, because a God without form, without a concrete personality, is not an object of the senses. If we can’t learn what will please God’s senses and engage in His service accordingly, then we’ll simply use our senses materially.

But our constitutional need as spiritual souls, part and parcel of God, is to have a personal loving relationship with Him. Although now we don’t know it, our deepest desire is to engage in loving pastimes with Krsna, because we’re eternally related to Him as devoted servants. So if we are to find spiritual satisfaction in our present materially embodied state, our constitutional need to love Krsna must be expressible through our sense activities here and now, in the material sphere. Learning to love Krsna by engaging our senses in practical devotional service to God is what Krsna consciousness, bhakti-yoga, is all about.

If our constitutional need to love Krsna is misdirected, then no matter how hard we try to enjoy a life centered on family and friends, career and fame. race and nation, or even a stunted conception of God, we’re on a self-destructive course. That’s a lesson I learned in part from John Berryman and The Dream Songs:

Hunger was constitutional with him, women, cigarettes, liquor, need,

need, need,

until he went to pieces,

Berryman’s artistic efforts and search for truth yielded no ultimate answers. “I have no idea whether we live again. It doesn’t seem likely … If I say Thy name, an thou there? It may be so.” Here was a man confessing his ignorance of God.

Srila Prabhupada, however, was a fully self-realized soul. Through his Bhagavad-gita As It Is he convinced me to try to realize my self by practicing bhakti-yoga, beginning with the chanting of the holy names of God: Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. Chanting these names, the Vedas declare, is the most effective method of self-realization in the present degraded age.

The Dream Songs reveals a desperate man, a poor soul plagued by the ills of lust and mortality. I feel deeply grateful that I met another teacher, His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, who was unaffected by those ills and who offered me the invaluable cure for them in the form of Krsna’s song. Now, at last, I feel I’m waking up from the nightmare that consumed Professor Berryman.

Leave a Reply