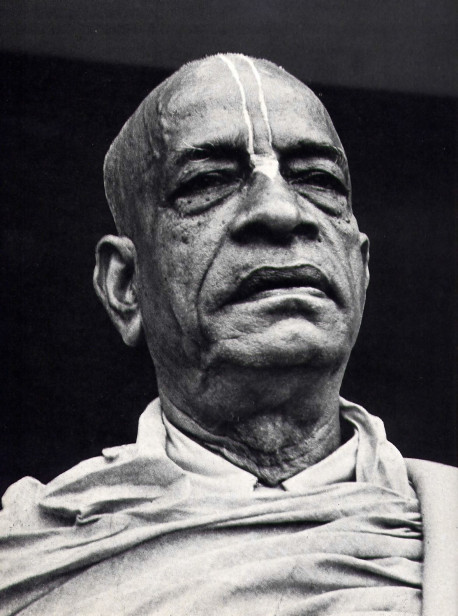

The Biography of a Pure Devotee

1966: The Lower East Side, New York.

The building was humble, the membership small,

yet Srila Prabhupada’s vision encompassed the whole world.

by Srila Satsvarupa dasa Goswami

Amid the cacophony of a storefront at 26 Second Avenue in New York, Srila Prabhupada had begun teaching the science of Krsna consciousness to a motley congregation drawn from the local community. Then, in his characteristically farseeing way, he founded the International Society for Krishna Consciousness.

We shall call our society ‘ISKCON.’ ” Prabhupada laughed playfully when he first coined the acronym.

He had initiated the legal work of incorporation that spring, while still living on the Bowery. But even before its legal beginning, Prabhupada had been talking about his “International Society for Krishna Consciousness,” and so it had appeared in letters to India and in The Village Voice. A friend had suggested a title that would sound more familiar to Westerners, “International Society for God Consciousness,” but Prabhupada had insisted: “Krishna Consciousness.” “God” was a vague term, whereas “Krishna” was exact and scientific; “God consciousness” was spiritually weaker, less personal. And if Westerners didn’t know that Krsna was God, then the International Society for Krishna Consciousness would tell them, by spreading His glories “in every town and village.”

“Krsna consciousness” was Prabhupada’s own rendering of a phrase from Srila Rupa Goswami’s Padyavali, written in the sixteenth century. Krsna-bhakti-rasa-bhavita. “to be absorbed in the mellow taste of executing devotional service to Krsna.”

But to register ISKCON legally as a nonprofit, tax-exempt religion required money and a lawyer. Carl Yeargens had already had some experience in forming a religious organization, and when he had met Prabhupada on the Bowery he had agreed to help. He had contacted his lawyer, a young Jewish man named Stephen Goldsmith.

Stephen Goldsmith had a wife and two children and an office on Park Avenue, yet he maintained an interest in spirituality. When Carl told him about Prabhupada’s plans, he was immediately fascinated by the idea of setting up a religious corporation for an Indian swami. He visited Prabhupada at 26 Second Avenue, and they discussed incorporation, tax exemption, Prabhupada’s immigration status—and Krsna consciousness. Mr. Goldsmith visited Prabhupada several times. Once he brought his children, who liked the “soup” Prabhupada cooked. He began attending the evening lectures, where he was often the only nonhippie member of the congregation. One evening, having completed all the legal groundwork and being ready to complete the procedures for incorporation, Mr. Goldsmith came to Prabhupada’s lecture and kirtana to get signatures from the trustees for the new society.

July 11. Prabhupada is lecturing.

Mr. Goldsmith, wearing slacks and a shirt and tie, sits on the floor near the door, listening earnestly to the lecture, despite the distracting noises from the neighborhood.

Prabhupada has been explaining how scholars mislead innocent people with nondevotional interpretations of the Bhagavad-gita. Now, in recognition of the attorney’s respectable presence, and as if to catch up Mr. Goldsmith’s attention better, Prabhupada introduces him into the subject of the talk.

I will give you a practical example of how things are misinterpreted. Just like our president, Mr. Goldsmith, he knows that expert lawyers, by interpretation, can do so many things. When I was in Calcutta, there was a rent tax passed by the government, and some expert lawyer changed the whole thing by his interpretation. The government had to reenact a whole law, because their purpose was foiled by the interpretation of this lawyer. So we are not out for foiling the purpose of Krsna, for which the Bhagavad-gita was spoken. But unauthorized persons are trying to foil the purpose of Krsna. Therefore, that is unauthorized.

All right, Mr. Goldsmith, you can ask anything.

Mr. Goldsmith stands, and to the surprise of the people gathered, he makes a short announcement asking for signers on an incorporation document for the Swami’s new religious movement.

Prabhupada: They are present here. You can take the addresses now.

Mr. Goldsmith: I can take them now, yes.

Prabhupada: Yes, you can. Bill, you can give your address. And Raphael, you can give yours. And Don…. Raymond. … Mr. Greene.

As the meeting breaks up, those called to sign as trustees come forward, standing around in the little storefront, waiting to leaf passively through the pages the lawyer has produced from his thin attache, and to sign as he directs. Yet not a soul among them is committed to Krsna consciousness. The lawyer meets his quota of signers, but they’re merely a handful of sympathizers who feel enough reverence toward the Swami to want to help him.

The first trustees, who will hold office for a year, “until the first annual meeting of the corporation,” are Michael Grant (who puts down his name and address without reading the document), Mike’s girlfriend Jan, and James Greene. No one seriously intends to undertake any formal duties as trustee of the religious society, but they are happy to help the Swami by signing his fledgling society into legal existence.

According to law, a second group of trustees will assume office for the second year. They are Paul Gardiner, Roy, and Don. The trustees for the third year of office are Carl Yeargens, Bill Epstein, and Raphael.

No one knows exactly what the half-dozen legal-sized typed pages mean, except that “Swamiji is forming a society.” Why?

For tax exemption, in case someone gives a big donation, and for other benefits an official religious society might receive.

But these purposes hardly seem urgent or even relevant to the present situation in the little storefront. Who’s going to make donations? Except maybe for Mr. Goldsmith, who has any money?

But Prabhupada is planning for the future, and he’s planning for much more than just tax exemptions. He is trying to serve his spiritual predecessors and fulfill the scriptural prediction of a spiritual movement that is to flourish for ten thousand years in the midst of the Age of Kali. Within the vast Kali Age (a period that is to last 432,000 years), the 1960s are an insignificant moment.

The Vedas describe that the time of the universe revolves through a cycle of four “seasons,” or yugas, and Kali-yuga is the worst of times, in which all spiritual qualities of men diminish, until humanity is finally reduced to a bestial civilization devoid of human decency. Yet for ten thousand years after the advent of Lord Caitanya there is the possibility of a Golden Age of spiritual life, an eddy that runs against the current of Kali-yuga. With a vision that soars off to the end of the millennium and far beyond, and yet with his two feet planted solidly on Second Avenue, Srila Prabhupada has begun an International Society for Krishna Consciousness. He has many practical responsibilities: he has to pay the rent, and he has to incorporate his society and pave the way for a thriving worldwide congregation of devotees. Somehow, he doesn’t see his extremely reduced present situation as a deterrent from the greater scope of his divine mission. He knows that everything depends on Krsna, so whether he succeeds or fails is all up to the Supreme. He has only to try.

The purposes stated within ISKCON’s articles of incorporation reveal Prabhupada’s thinking. They are seven points, similar to those given in the Prospectus for the League of Devotees he had formed in Jhansi, India, in 1953. That attempt had been unsuccessful, yet his purposes remained unchanged.

Seven Purposes of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness:

1. To systematically propagate spiritual knowledge to society at large and to educate all peoples in the techniques of spiritual life in order to check the imbalance of values in life and to achieve real unity and peace in the world.

2. To propagate a consciousness of Krsna, as it is revealed in the Bhagavad–gita and Srimad–Bhagavatam.

3. To bring the members of the Society together with each other and nearer to Krsna, the prime entity, and thus to develop the idea within the members and humanity at large that each soul is part and parcel of the quality of Godhead (Krsna).

4. To teach and encourage the sankirtana movement, congregational chanting of the holy name of God as revealed in the teachings of Lord Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu.

5. To erect for the members and for society at large a holy place of transcendental pastimes dedicated to the Personality of Krsna.

6. To bring the members closer together for the purpose of teaching a simpler and more natural way of life.

7. With a view towards achieving the aforementioned purposes, to publish and distribute periodicals, magazines, books and other writings.

Regardless of how ISKCON’s charter members regarded the Society’s purposes, Srila Prabhupada saw them as imminent realities. As Mr. Ruben, the subway conductor who had met Prabhupada on a Manhattan park bench in 1965, remembers, “He seemed to know that he would have temples filled up with devotees. ‘There are temples and books,’ he said. ‘They are existing, they are there, but the time is separating us from them.’ “

The first purpose mentioned in the charter was propagation. “Preaching” was the word Prabhupada most often used. For him, preaching had a much broader significance than mere sermonizing. Preaching meant glorious, selfless adventures on behalf of the Supreme Lord. Lord Caitanya had preached by walking all over southern India and inducing thousands of people to chant and dance with Him in ecstasy. Lord Krsna had preached the Bhagavad–gita while standing with Arjuna in his chariot on the Battlefield of Kuruksetra. Lord Buddha had preached, Lord Jesus had preached, and all other pure devotees preached.

ISKCON’s preaching would achieve what the League of Nations and the United Nations had failed to achieve—”real unity and peace in the world.” ISKCON workers would bring peace to a world deeply afflicted by materialism and strife. They would “systematically propagate spiritual knowledge,” knowledge of the nonsectarian science of God. It was not that a new religion was being born in July of 1966; rather, the eternal preaching of Godhead, known as sankirtana, was being transported from East to West. And this new consciousness in the West would come about through the teachings of Bhagavad–gita and Srimad-Bhagavatam.

The Society’s members would come together, and by hearing the philosophy of Krsna consciousness and chanting the Hare Krsna mantra in mutual association they would realize that each was a spirit soul, eternally related to Krsna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead. They would then preach these realizations to “humanity at large,” especially through sankirtana, the chanting of the holy name of God.

ISKCON would also erect “a holy place of transcendental pastimes dedicated to the Personality of Krsna.” Was this something beyond the storefront? Yes, certainly. He never thought small: “He seemed to know that he would have temples filled up with devotees.”

He wanted ISKCON to demonstrate “a simple, more natural way of life.” Such a life (Prabhupada thought of the villages of India, where people lived just as Krsna had lived) was most conducive to developing Krsna consciousness.

And all six of these purposes would be achieved by the seventh: ISKCON would publish and distribute literature. This was the special instruction given to Srila Prabhupada by Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura, who had specifically told him one day in 1935 at Radha-kunda in Vrndavana, “If you ever get any money, publish books.”

Certainly none of the signers saw any immediate shape to Prabhupada’s dream, yet these seven purposes were not simply theistic rhetoric invented to convince a few New York State government officials. He literally meant to enact every item in the charter.

Of course, he was now working in extremely limited circumstances. The sole headquarters for the International Society for Krishna Consciousness was “the principal place of worship, located at 26 Second Avenue in the city, county, and state of New York.” Yet Prabhupada insisted that he was not living at 26 Second Avenue, New York City. His vision was different. His Guru Maharaja had gone out from the traditional holy places of spiritual meditation to preach in cities like Calcutta, Bombay, and New Delhi. And yet Prabhupada would say that his spiritual master had not really been living in any of those cities, but was always in Vaikuntha, the spiritual world, because of his absorption in devotional service.

Similarly, the place of worship, 26 Second Avenue, was not a New York storefront, a former curiosity shop. It was a small place, but it had now been spiritualized. The storefront and the apartment were now a transcendental haven. “Society at large” could come here, the whole world could take shelter here, regardless of race or religion. Plain, small, and impoverished as it was, Prabhupada regarded the storefront as “a holy place of transcendental pastimes, dedicated to the Personality of Krsna:” It was a world headquarters, a publishing house. a sacred place of pilgrimage, and a center from which an army of devotees could issue forth and chant the holy names of God in all the streets in the world. The entire universe could receive Krsna consciousness from the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, which was beginning here.

(To be continued)

Leave a Reply