Fraternity in Krsna consciousness

“As I began to spend more time with the brahmacaris, I noticed an unusual trait. They seemed to be always joyful, beyond the moody ups and downs that had plagued my spiritual quest.”

by Kalakantha Dasa

“What would happen to me if I wanted to become a Hare Krsna devotee?” a young man recently asked me. The first step, I told him, would be to enter the brahmacari asrama, the status of life for single men serious about spiritual advancement. Though I am now happily married, the conversation reminded me of the years I spent as a brahmacari.

My first encounter with brahmacaris came in 1972 in Portland, Oregon. Although my parents had kindly offered me many good opportunities to establish a professional career, I kept finding “higher education” empty and unsatisfying. So, at the time, I was maintaining myself with a simple job, using my spare time to indulge my fascination with the Bible and other spiritual teachings.

One day as I was rushing around downtown Portland delivering office supplies, I was shocked by the sight of seven or eight shaven-headed, saffron-clad men dancing, playing cymbals and drums, and singing the Hare Krsna mantra: Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. I pulled over to watch, and after a few minutes one of the young men approached me with a smile and a book, Sri Isopanisad. I gave him a dollar and gratefully accepted the book.

That night in my apartment I sat down to read the Sri Isopanisad. It was intriguing because it was apparently speaking to me from a higher platform. But it was also bewildering. It seemed difficult and foreign, as were many of the other spiritual texts I had tried to read.

But this text had something extra: a person to explain it! I called the local Hare Krsna temple and arranged to meet the young man who had sold me the book.

Carrying no intentions of changing my dress or hairstyle, I entered the temple, a two-story brick house in a pleasant neighborhood. I met my exotic-looking friend and sat with him on the carpeted floor of the reception room, where we discussed Sri Isopanisad. Soon the text began to make sense to me, and I became curious about my friend’s peculiar mode of life. He explained that he was a brahmacari, a celibate student devoted to spiritual study. He lived and worked under the tutelage of his guru, His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, founder and spiritual master of the Hare Krsna movement. Curious, I asked him to tell me more about the brahmacari’s life.

“Oh, I can do better than that,” he said. “Come on.” And he took me to the brahmacari quarters, a spotlessly clean bedroom full of bunks and lockers. On each bunk was a bookrack sporting many of Srila Prabhupada’s books. Pictures of Krsna and neat, hand-printed verses from the Bhagavad-gita decorated the walls.

“Brahmacaris live as simply as possible,” my friend said. The shaven head and saffron robes, he explained, indicate (to an informed observer) the status of a celibate monk. The brahmacari’s appearance is traditional and designed for cleanliness and simplicity.

Later I read from the Srimad-Bhagavatam, a five-thousand year old Sanskrit text, about the classical definition of brahmacari life:

The brahmacari should live under the care of the true spiritual master, giving him sincere respect and obeisances, acting as his menial servant and carrying out his order. The brahmacari should engage himself in spiritual activities and study the Vedic literature under the direction of the spiritual master. He should collect alms daily in the morning and in the evening. Whatever alms he has collected he should offer to the spiritual master. The brahmacaris should be satisfied with eating what is absolutely necessary, he should be very expert in executing responsibilities, he should be faithful, and he should control his senses and try to avoid the association of the opposite sex as far as possible.

It didn’t take long for me to observe some differences between the lives of the Hare Krsna brahmacaris and those of their traditional Vedic predecessors. Although they were enthusiastic to minimize their corporeal demands and to study and discuss the scriptures, my Hare Krsna friends also drove cars, used washing machines, and conducted an incense business to “collect alms.” “Such materialism in a spiritual movement,” I thought.

But was it materialism? As I learned more about the Vedic philosophy of yukta-vairagya (practical renunciation), I came to see that the brahmacaris’ seeming materialism was fully spiritual. Srila Prabhupada explains that material things are material only if they are used for selfgratification. If the same material thing is used for serving God, Krsna, it becomes spiritualized. Although traditionally a brahmacari’s life is one of obvious renunciation and austerity, a brahmacari, for better serving his guru, will utilize the latest advancements in technology and will live within materialistic society. By utilizing material things only in the spiritual service of Lord Krsna, he remains aloof and transcendental. When I understood that, my brahmacari friends’ wristwatches, sleeping bags, tape players, and electric shavers never bothered me again.

Then I noticed another apparent discrepancy. Traditionally one guru would train ten or twelve brahmacaris. But Srila Prabhupada had accepted thousands of brahmacari disciples (what to speak of female and married disciples) all over the world. How could he offer the same intimate training to so many? I soon discovered Srila Prabhupada’s method: he regularly corresponded with and met with his senior disciples and temple presidents. Younger disciples were directed to take instruction from them. (This system has continued since Srila Prabhupada’s passing in 1977, with his senior disciples now initiating and training their own disciples all over the world.) More importantly, Srila Prabhupada was busily producing his English translations and commentaries on the Vedic scriptures. Through his prolific writings (he eventually published over eighty books), Srila Prabhupada was reaching thousands around the world.

As I began to spend more time with the brahmacaris, I noticed an unusual trait. They seemed to be always joyful, far beyond the moody ups and downs that had plagued my spiritual quest. They were always eager to talk with me about Krsna, and they spoke with impressive conviction and insight. Their discussions about spiritual advancement were clear and comprehensible, not the uncertain, sentimental, or sometimes fanatical stuff I always seemed to get elsewhere.

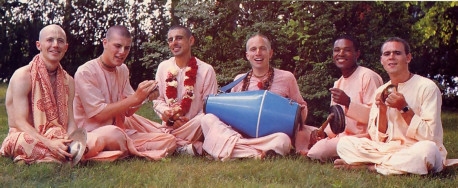

These brahmacaris were more than dry, austere yogis. They performed kirtana (congregational chanting of the Hare Krsna mantra) with authentic Indian musical instruments: mrdangas (two-headed clay drums), karatalas (brass hand cymbals), and a harmonium (a small hand-pumped reed organ). As devotees played those instruments and chanted the Hare Krsna mantra to beautiful Bengali melodies, the rock and roll musician in me came out. I decided to learn all these fascinating spiritual instruments.

Some of the brahmacaris were expert cooks. On Sundays they churned out huge pots and vats full of pleasantly spiced vegetable dishes, puris (a whole-wheat bread deep-fried in clarified butter), strawberry malpura (soft, sweet cakes floating in fruit-flavored yogurt), and various unimaginably delightful drinks, savories, chutneys, and sweets. My self-imposed vegetarian regime of millet, rice, and sprouts couldn’t compare. I had no idea spiritual life could be full of such delicious variety!

As I spent more time at the temple, I was impressed with the vigor and enthusiasm with which the brahmacaris attacked their daily services. One brahmacari was in charge of purchasing. Another kept the temple accounts. Another led the daily chanting party and gave lectures in the temple. Unlike myself, they did not seem to look forward to getting the weekends off. They put in a full day every day, and they seemed to be genuinely enjoying themselves in the process.

My brahmacari friend taught me about japa (chanting the Hare Krsna mantra while counting on a strand of one-hundred eight beads, one mantra per bead.) And he explained to me the four regulative principles (abstinence from meat-eating, gambling, intoxication, and illicit sex). I began practicing these prerequisites at home and soon moved into the temple. After several months I was recommended by the temple president for formal initiation. A short time later Srila Prabhupada accepted me as his duly initiated brahmacari disciple. Though I met with Srila Prabhupada only occasionally, through his books and senior disciples I developed a deep and personal relationship with him.

Recently I met a young man who told me of his experiences with another “guru.” He had spent $250 (and three days sleeping in his car) for the privilege of receiving “knowledge”—a swat on the head with a peacock fan. Thus he had been “initiated.” This poor fellow further explained that the more $250 swats he received, the more enlightened he would become.

How simple. A kind of freeze-dried enlightenment! No commitments. No follow-up. No personal care required. It is very easy to find a guru who can take away your money, but very hard to find one who can take your material desires. This young man’s unfortunate contact with pseudo-spiritual life made me appreciate how well Srila Prabhupada and his disciples who have become gurus take care of their disciples.

I never regretted my decision to become a Hare Krsna brahmacari. Over the next ten years I drank deeply of the sublime Krsna conscious philosophy, learning Sanskrit and Bengali verses and putting them into daily practice. I learned to cook, play instruments, manage groups of people, I deliver public lectures, and perform dozens of other skills. Although I worked always without pay, my basic needs were met and my service took me throughout America, Europe, and India. I enjoyed the opportunity of sharing Krsna consciousness with all kinds of people—the rich, the poor, the learned, the simple. I’ve become acquainted with hundreds of other members of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness from all over the world; thus I find friends nearly everywhere I go.

As much as I loved my brahmacari years, eventually I realized that I was not cut out to remain a single, celibate monk throughout life.

Brahmacari Principles In Married Life

Celibacy ties in well with the goals of brahmacari life. Preserving sexual energies endows one with a clear mind, a powerful memory, and the determination to conquer bad habits. Traditionally, brahmacari life should begin at age five, and last until twenty-five. Then the brahmacari may decide whether to remain celibate or to marry.

When I began to look into Krsna conscious marriage, I learned that I could put my brahmacari training to good use. Married (grhastha) life should be led very simply, and scriptural study should continue. One should continue to work under the direction of the guru, and one should refrain from sex except for conceiving children. One who observes such a regulated life is known as a grhastha-brahmacari.

You might wonder what traditional Vedic culture has against sex. Isn’t sex natural? Yes. But it must be regulated. Most members of the animal kingdom mate only during certain seasons, with the goal of procreation. They do not use synthetic devices or pills to prevent pregnancy, nor do they terminate inconvenient pregnancies. They are regulated through nature’s laws. Human life is unique in that we must voluntarily accept the regulation of God’s laws for humanity. In a vain attempt to replace spiritual happiness with natural sex pleasure, human beings go to unnatural extremes. Brahmacari life makes the conquest of sex desire both achievable and enjoyable by replacing it with the superior pleasure of spiritual awakening.

When I was considering marriage, it was good to know that though celibacy is highly valued, a brahmacari does not have to lose his spiritual qualifications if he marries. Nevertheless, a strong espirit de corps among the Hare Krsna brahmacaris helps them refrain from marriage as long as possible.

With some adaptations, the same principles of brahmacari life also apply to single women, who are known as brahmacarinis. Srila Prabhupada has left a unique legacy: a spiritual institution in the modern, materialistic world that freely gives personal, profound spiritual training to young men and women.

Why Be a Brahmacari?

When I became a brahmacari, my parents were displeased and accused me of the ultimate self-indulgence: “What good does it do the world for you to sit and meditate all day?” Eventually, though, they observed that Hare Krsna brahmacaris work hard at what they do. It’s not lotus postures and nirvana all day and night. Rather, brahmacaris study, practice, and distribute Srila Prabhupada’s teachings according to their sincere conviction.

Like to do some good for the world? Lord Sri Krsna Caitanya, who fathered the Hare Krsna movement in Bengal five hundred years ago, gave the recommendation: “First become perfect, then teach.” Shouldn’t social reform and welfare work begin at home? By learning about brahmacari life, or just by chanting Hare Krsna, we can begin to perfect our own lives. And won’t that make the whole world a little better off?

Leave a Reply