Carrying Krsna’s Message to the West

1953-1965: India.

After writing and printing three volumes of Vedic knowledge,

Srila Prabhupada was ready to embark on his journey to America.

by Srila Satsvarupa dasa Goswami

(Condensed from Srila Prabhupada-lilamrta, by Satsvarupa dasa Goswami.

In October of 1952, Abhay Charan De, as Srila Prabhupada was then known, began preaching Krsna consciousness in Jhansi, India, about 150 miles west of Allahabad. With the support of local doctors and businessmen, he began an organization—the League of Devotees—dedicated to spreading Krsna consciousness in India and abroad.

The organization failed, but Srila Prabhupada persevered. He retired from his business and family life, and on September 17, 1959, he accepted sannyasa, the order of renunciation. Thus he became known as A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami.

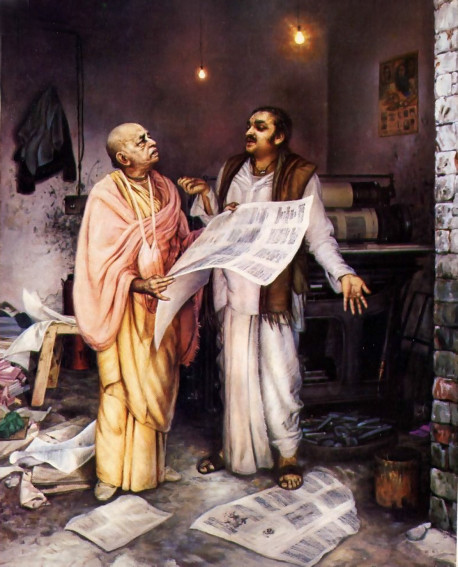

He continued working to spread Krsna consciousness—in Delhi, Vrndavana, Bombay, and elsewhere. He published several issues of his newspaper, Back to Godhead. But then a librarian suggested that he write books, since books were permanent where-as newspapers would be read once and then thrown away. Srila Prabhupada took this suggestion most seriously, considering it to have come to him by the grace of his spiritual master.

As a dependent servant constantly meditating on the desires of his transcendental master and seeking his guidance, Bhaktivedanta Swami felt his spiritual master’s reciprocal blessings and personal presence. More and more he was feeling confidential contact with Srila Bhaktisiddhanta, and now he was feeling an inspiration to write books.

He considered Srimad-Bhagavatam, because it was the most important and authoritative Vaisnava scripture. Although Bhagavad-gita was the essence of all Vedic knowledge, presented in a brief ABC fashion, Srimad-Bhagavatam was elaborate. An English translation and commentary for this book could one day change the hearts of the entire world. And if he could publish even a few books, his preaching would be enhanced; he could go abroad with confidence and not appear empty-handed.

In presenting the literary incarnation of God, Srimad-Bhagavatam, for the benefit of the Western world, Bhaktivedanta Swami realized that he was performing an important task, following in the footsteps of the book’s original author, Srila Vyasadeva. As Srila Vyasadeva had had a vision of Krsna and had received direction from his spiritual master before beginning his literary mission, Bhaktivedanta Swami had his vision and had received instructions from his spiritual master. Bhaktivedanta Swami envisioned distributing in mass the book of Srila Vyasadeva. He would not merely translate it; he would personally take it to the West, present it, and teach people in the West—through the book and in person—how to develop pure love of God.

While residing in the holy city Vrndavana, Bhaktivedanta Swami immersed himself in his work of translation and commentary.

But writing was only half the battle; the other half was publishing. Bhaktivedanta Swami personally had to shoulder all the responsibility for raising funds, printing the books, and getting the copies sold.

Moving back and forth between Vrndavana and Delhi, he managed to write and publish the first two volumes of what he aspired to present as a sixty-volume set.

To raise funds for Volume Three, Bhaktivedanta Swami decided to try Bombay. He traveled there in July and stayed at the Premkutir Dharmashala, a free asrama. He made his rounds of the institutions and booksellers in Bombay. He now had an advertisement showing himself with Prime Minister Shastri, and he also had the prime minister’s letter recommending the book to government libraries, and the Ministry of Education’s purchase order for fifty volumes. Still, he was getting only small orders.

Then he decided to visit Sumati Morarji, head of the Scindia Steamship Company. He had heard from his God-brothers in Bombay that she was known for helping sadhus, saintly persons, and had donated to the Bombay Gaudiya Math. He had never met her, but he well remembered the 1958 promise by one of her officers to arrange half-fare passage for him to America. Now he wanted her help for printing Srimad-Bhagavatam.

But his first attempts to arrange a meeting were unsuccessful. Frustrated at being put off by Mrs. Morarji’s officers, he sat down on the front steps of her office building, determined to catch her attention as she left for the day. The lone sadhu certainly caused some attention as he sat quietly chanting for five hours on the steps of the Scindia Steamship Company building. Finally, late that afternoon, Mrs. Morarji emerged in a flurry of business talk with her secretary, Mr. Choksi. Upon seeing Bhaktivedanta Swami, she stopped. “Who is this gentleman sitting here?” she asked Mr. Choksi.

“He’s been here for five hours,” the secretary said.

“All right, I’ll come,” she said and walked up to where Bhaktivedanta Swami was sitting. He smiled and stood, offering namaskaras with his folded palms. “Swamiji, what can I do for you?” she said.

Bhaktivedanta Swami told her briefly of his intentions to print the third volume of his Srimad-Bhagavatam. “I want you to help me,” he said.

“All right,” Mrs. Morarji replied. “We can meet tomorrow, because it is getting late. Tomorrow you can come, and we will discuss.”

The next day, Bhaktivedanta Swami met with Mrs. Morarji in her office, where she looked at the typed manuscript and the published volumes. “All right,” she said, “if you want to print it, I will give you the aid. Whatever you want. You can get it printed.”

With Mrs. Morarji’s guarantee, Bhaktivedanta Swami was free to return to Vrndavana to finish writing the manuscript. As with the previous volumes, he set a demanding schedule for writing and publishing. The third volume would complete the First Canto. Then, with a supply of impressive literature, he would be ready to go to the West.

With the manuscript for Volume Three complete and with the money to print it, Bhaktivedanta Swami once again entered the printing world, purchasing paper, correcting proofs, and keeping the printer on schedule so that the book would be finished by January 1965. Thus, by his persistence, he who had almost no money of his own managed to publish his third large hardbound volume within a little more than two years.

At this rate, with his respect in the scholarly world increasing, he might soon become a recognized figure amongst his countrymen. But he had his vision set on the West. And with the third volume now printed, he felt he was at last prepared. He was sixty-eight and would have to go soon. It had been more than forty years since Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati had first asked a young householder in Calcutta to preach Krsna consciousness in the West. At first it had seemed impossible to Abhay Charan, who had so recently entered family responsibilities. That obstacle, however, had long ago been removed, and for more than ten years he had been free to travel. But he had been penniless (and still was). And he had wanted first to publish some volumes of Srimad-Bhagavatam to take with him; it had seemed necessary if he were to do something solid. Now, by Krsna’s grace, three volumes were on hand.

Then Bhaktivedanta Swami met Mr. Agarwal, a Mathura businessman, and mentioned to him in passing, as he did to almost everyone he met, that he wanted to go to the West. Although Mr. Agarwal had known Bhaktivedanta Swami for only a few minutes, he volunteered to try to get him a sponsor in America. It was something Mr. Agarwal had done a number of times; when he met a sadhu who mentioned something about going abroad to teach Hindu culture, he would ask his son Gopal, an engineer in Pennsylvania, to send back a sponsorship form. When Mr. Agarwal offered to help in this way, Bhaktivedanta Swami urged him to please do so.

Srila Prabhupada: I did not say anything seriously to Mr. Agarwal, but perhaps he took it very seriously. I asked him, “Well, why don’t you ask your son Gopal to sponsor so that I can go there? I want to preach there.”

To Bhaktivedanta Swami’s surprise, he was soon contacted by the Ministry of External Affairs and informed that his No Objection certificate for going to the U.S. was ready. Since he had not instigated any proceedings for leaving the country, Bhaktivedanta Swami had to inquire from the ministry about what had happened. They showed him the Statutory Declaration Form signed by Mr. Gopal Agarwal of Butler, Pennsylvania; Mr. Agarwal solemnly declared that he would bear the expenses of Bhaktivedanta Swami during his stay in the U.S.

Now Bhaktivedanta Swami had a sponsor. But he still needed a passport, visa, P-form, and travel fare. After securing his passport without much difficulty, he went to Bombay, not to sell books or raise funds for printing; he wanted a ticket for America. Again he tried approaching Sumati Morarji. He showed his sponsorship papers to her secretary, Mr. Choksi, who was impressed and who went to Mrs. Morarji on his behalf. “The Swamiji from Vrndavana is back,” he told her. “He has published his book on your donation. He has a sponsor, and he wants to go to America. He wants you to send him on a Scindia ship.” Mrs. Morarji said no, the Swami was too old to go to the United States and expect to accomplish anything. As Mr. Choksi conveyed to him Mrs. Morarji’s words, Bhaktivedanta Swami listened disapprovingly. She wanted him to stay in India and complete the Srimad-Bhagavatam. Why go to the States? Finish the job here.

But Bhaktivedanta Swami was fixed on going. He told Mr. Choksi that he should convince Mrs. Morarji. He coached Mr. Choksi on what he should say: “I find this gentleman very inspired to go to the United States and preach something to the people there. . . .” But when he told Mrs. Morarji, she again said no. The Swami was not healthy. It would be too cold there. He might not be able to come back, and she doubted whether he would be able to accomplish much there. People in America were not so cooperative, and they would probably not listen to him.

Exasperated with Mr. Choksi’s ineffectiveness, Bhaktivedanta Swami demanded a personal interview. It was granted, and a grey-haired, determined Bhaktivedanta Swami presented his emphatic request: “Please give me one ticket.”

Sumati Morarji was concerned. “Swamiji, you are so old—you are taking this responsibility. Do you think it is all right?”

“No,” he reassured her, lifting his hand as if to reassure a doubting daughter, “it is all right.”

“But do you know what my secretaries think? They say, ‘Swamiji is going to die there.'”

Bhaktivedanta made a face as if to dismiss a foolish rumor. Again he insisted that she give him a ticket. “All right,” she said. “Get your P-form, and I will make an arrangement to send you by our ship.” Bhaktivedanta Swami smiled brilliantly and happily left her offices, past her amazed and skeptical clerks.

A “P-form”—another necessity for an Indian national who wants to leave the country—is a certificate given by the State Bank of India, certifying that the person has no excessive debts in India and is cleared by the banks. That would take a while to obtain. And he also did not yet have a U.S. visa. He needed to pursue these government permissions in Bombay, but he had no place to stay. So Mrs. Morarji agreed to let him reside at the Scindia Colony, a compound of apartments for employees of the Scindia Company.

He stayed in a small, unfurnished apartment with only his trunk and typewriter. The resident Scindia employees all knew that Mrs. Morarji was sending him to the West, and some of them became interested in his cause. They were impressed, for although he was so old, he was going abroad to preach. He was a special sadhu, a scholar. They heard from him how he was taking hundreds of copies of his books with him, but no money. He became a celebrity at the Scindia Colony. Various families brought him rice, vegetables, and fruit. They brought so much that he could not eat it all, and he mentioned this to Mr. Choksi. Just accept it and distribute it, Mr. Choksi advised. Bhaktivedanta Swami then began giving remnants of his food to the children. Some of the older residents gathered to hear him as he read and spoke from Srimad-Bhagavatam. Mr. Vasavada, the chief cashier of Scindia, was particularly impressed and came regularly to learn from the sadhu. Mr. Vasavada obtained copies of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s books and read them in his home.

The Swami’s backing by Scindia and his sponsorship in the U.S. were a strong presentation, and with the help of the people at Scindia he obtained his visa on July 28, 1965. But the P-form proceedings went slowly and even threatened to be a last, insurmountable obstacle.

Srila Prabhupada: I had so much difficulty obtaining the government permission to go out. I had applied for the P-form sanction, but no sanction was coming. Then I went to the State Bank of India. The officer was Mr. Martarchari. He told me, “Swamiji, you are sponsored by a private man. So we cannot accept. If you were invited by some institution, then we could consider. But you are invited by a private man for one month. And after one month, if you are in difficulty, there will be so many obstacles.” But I had already prepared everything to go. So I said, “What have you done?” He said, “I have decided not to sanction your P-form.” I said, “No, no, don’t do this. You better send me to your superior. It should not be like that.”

So he took my request, and he sent the file to the chief official of foreign exchange—something like that. So he was the supreme man in the State Bank of India. I went to see him. I asked his secretary, “Do you have such-and-such a file. You kindly put it to Mr. Rao. I want to see him. ” So the secretary agreed, and he put the file, and he put my name down to see him. I was waiting. So Mr. Rao came personally. He said, “Swamiji, I passed your case. Don’t worry.”

Following Mrs. Morarji’s instruction, her secretary, Mr. Choksi, made final arrangements for Bhaktivedanta Swami. Since he had no warm clothes, Mr. Choksi took him to buy a wool jacket and other woolen clothes. Mr. Choksi spent about 250 rupees on new clothes, including some new dhotis. At Bhaktivedanta Swami’s request, Mr. Choksi printed five hundred copies of a small pamphlet containing the eight verses written by Lord Caitanya and an advertisement for Srimad-Bhagavatam, in the context of an advertisement for the Scindia Steamship Company.

Mr. Choksi: I asked him, “Why couldn’t you go earlier? Why do you want to go to the States, at this age?” He replied that, “I will be able to do something good, I am sure.” His idea was that someone should be there who would be able to go near people who were lost in life and teach them and tell them what the correct thing is. I asked him so many times, “Why do you want to go to the States? Why don’t you start something in Bombay or Delhi or Vrndavana?” I was teasing him also: “You are interested in seeing the States. All Swamijis want to go to the States, and you want to enjoy there.” He said, “What have I got to see? I have finished my life.”

Finally Mrs. Morarji scheduled a place for him on one of her ships, the Jaladuta, which was sailing from Calcutta on August 13. She had made certain that he would travel on a ship whose captain understood the needs of a vegetarian and a brahmana. Mrs. Morarji told the Jaladuta’s captain, Arun Pandia, to carry extra vegetables and fruits for the Swami. Mr. Choksi spent the last two days with Bhaktivedanta Swami in Bombay, picking up the pamphlets at the press, purchasing clothes, and driving him to the station to catch the train for Calcutta.

He arrived in Calcutta only a few days before the Jaladuta’s departure. Although he had lived much of his life in the city, he now had nowhere to stay. Although in this city he had been so carefully nurtured as a child, those early days were also gone forever. As he had written in a poem, “Vrndavana-bhajana,” “Where have my loving mother and father gone to now? And where are all my elders, who were my own folk? Who will give me news of them, tell me who? All that is left of this family life is a list of names.”

Out of the hundreds of people in Calcutta whom Bhaktivedanta Swami knew, he chose to call on Mr. Sisir Bhattacarya, the flamboyant kirtana singer he had met a year before at the governor’s house in Lucknow. Mr. Bhattacarya was not a relative, not a disciple, nor even a close friend; but he was willing to help. Bhaktivedanta Swami called at his place and informed him that he would be leaving on a cargo ship in a few days; he needed a place to stay, and he would like to give some lectures. Mr. Bhattacarya immediately began to arrange a few private meetings at friends’ homes, where he would sing and Bhaktivedanta Swami would then speak.

The day before his departure, Bhaktivedanta Swami traveled to nearby Mayapur to visit the samadhi tomb of Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati. Then he returned to Calcutta. He was ready.

He had only a suitcase, an umbrella, and a supply of dry cereal. He did not know what he would find to eat in America; perhaps there would be only meat. If so, he was prepared to live on boiled potatoes and the cereal. His main baggage, several trunks of his books, was being handled separately by Scindia Cargo. Two hundred three-volume sets—the very thought of the books gave him confidence.

When the day came for him to leave, he needed that confidence. He was making a momentous break with his previous life, and he was dangerously old and not in strong health. And he was going to an unknown and probably unwelcoming country. To be poor and unknown in India was one thing. Even in these Kali-yuga days. when India’s leaders were rejecting Vedic culture and imitating the West, it was still India; it was still the remains of Vedic civilization. He had been able to see millionaires, governors, the prime minister, simply by showing up at their doors and waiting. A sannyasi was respected; the Srimad-Bhagavatam was respected. But in America it would be different. He would be no one, a foreigner, and there were no temples, no free asramas, and no tradition of sadhus. But when he thought of the books he was bringing—transcendental knowledge in English—he became confident. When he met someone in the States he would give them a flyer: “‘Srimad-Bhagavatam,’ India’s Message of Peace and Goodwill.”

It was August 13, just a few days before Janmastami, the appearance day anniversary of Lord Krsna—the next day would be his own sixty-ninth birthday. During these years, he had been in Vrndavana for Janmastami. Many Vrndavana residents would never leave there; they were old and at peace in Vrndavana. Bhaktivedanta Swami was also concerned that he might die away from Vrndavana. That was why all the Vaisnava sadhus and widows had taken vows not to leave, even for Mathura—because to die in Vrndavana was the perfection of life. And the Hindu tradition was that a sannyasi should not cross the ocean and go to the land of the mlecchas (meat-eaters). But beyond all that was the desire of Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, and his desire was nondifferent from that of Lord Krsna. And Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu had predicted that the chanting of Hare Krsna would be known in every town and village of the world.

Mr. Bhattacarya and Bhaktivedanta Swami took a taxi down to the Calcutta port. Bhaktivedanta Swami was carrying a Bengali copy of Caitanya-caritamrta, which he intended to read during the crossing. Somehow he would be able to cook on board. Or if not, he could starve—whatever Krsna desired. He checked his essentials: passenger ticket, passport, visa, P-form, sponsor’s address. Finally it was happening.

The black cargo ship, small and weathered, was moored at dockside, a gangway leading from the dock to the ship’s deck. Indian merchant sailors curiously eyed the elderly saffron-dressed sadhu as he spoke last words to his companion in the taxi and then left him and walked determinedly towards the boat.

Mr. Bhattacarya: He was alone. A lone fighter. When he left, there was no one to bid him good-bye. No friends, no supporter, no disciple, nobody. So, I was the only person standing on the shore to say him good-bye. I could not know that it was such an important thing.

For thousands of years, krsna-bhakti had been known only in India, not outside, except in twisted, faithless reports by foreigners. And the only swamis to have reached America had been nondevotees, Mayavadi impersonalists. But now Krsna was sending Bhaktivedanta Swami as His emissary.

This installment from Srila Prabhupada-lilamrta, the biography of a pure devotee, brings us to the end of Volume One. It also ends our BACK TO GODHEAD series of excerpts from this multivolume work. The first three volumes are now in print, and the fourth is soon going to press. We expect the work to be complete in six or seven volumes.

To keep reading this story of Srila Prabhupada’s life, ask for the books in this series from your local ISKCON center. Or write to ISKCON Educational Services, 3764 Watseka Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90034.

Leave a Reply