Confusing “cast” with “caste” is an innocent error, but mistaking Lord Krsna’s varnasrama system for an oppressive, hereditary class structure is a far more serious blunder.

By Mathuresa Dasa

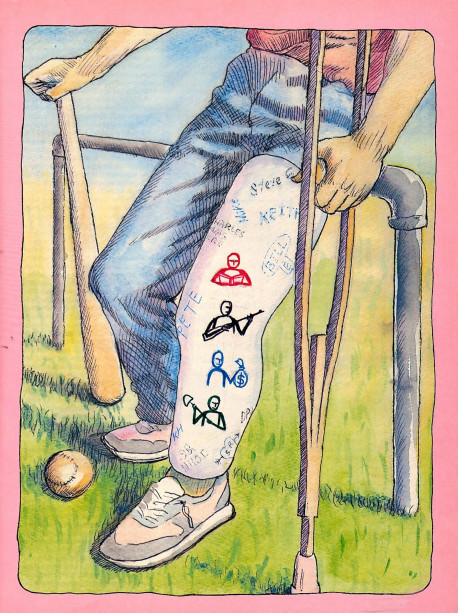

Baseball, to most anyone’s mind, has little in common with the Indian caste system, which rigidly divides society into four hereditary classes. But for me there’s a subtle link between the two, as the result of an injury I sustained while at bat during an impromptu after-dinner game in the early spring of 1967. My school friend Bill Lightbody was pitching, his sister and two brothers fielded, and the three Lightbody family dogs ran noisily after whoever had the ball. Selecting a likely pitch, I zeroed in and swung hard. My torso turned gracefully with the swing, but my left foot stuck tightly in some early-spring mud. The combination of twisting torso and stuck foot gracefully tore a ligament in my left knee.

Next morning the doctor drained half a cup of fluid from the swollen joint and set my leg, thigh to ankle, in a plaster cast that chafed and itched me to distraction. Three weeks later, when the doctor removed the cast, I found that my leg, though healed, was weak and shrunken from disuse and had turned an unsightly pale brown. Although a month or so of special exercises returned me to form, nevertheless I had missed most of the spring backyard season, sidelined by a freak accident and an ungainly hunk of plaster.

Indian castes also sidelined people—for life. At least that’s the understanding I had gleaned from grade school courses in world history. In the caste system you were by birth either a brahmana (intellectual or priest), ksatriya (soldier or administrator), vaisya (farmer or merchant), or sudra (artisan or laborer). Caste kids, I learned, were never asked, “What do you want to be when you grow up? A fireman? A doctor? A baseball player? The President?” If Dad was a ditch-digger, caste kids dug ditches; if he was a pencil-pusher, they pushed pencils. And, cruelest of all, if a ditch-digger’s son and a pencil-pusher’s daughter got a crush on each other, forget it. No inter-caste marriages. In so many ways, caste designations, which were freak accidents of heredity, kept people from playing the game of life. It’s not that I spent the spring evenings of 1967 silently commiserating with caste-bound Indians, but camouflaged in the underbrush of my unspoken thoughts, ”cast” and “caste” walked hand in hand.

Yes, I know, the words “cast,” as in “itchy plaster cast,” and “caste,” as in “oppressive Indian caste system,” have completely different origins. They are homophones—words that sound the same but share no etymological roots. “Cast” derives from the Middle English casten, “to throw,” while “caste” derives from the Portuguese casta, meaning “race,” “lineage,” or “breed.” But so what? A lot of people make the same mistake. Only a couple of centuries ago the two words had exactly the same spelling. And besides, even now, years after my own etymological enlightenment, I can’t think of anything that better conveys the idea of the stifled hopes, shattered dreams, wasted abilities, and frustrated ambitions for which the caste system is allegedly responsible than the image of a weak, shriveled, discolored limb wrapped tightly in gauze and plaster of Paris. Cast vividly illustrates caste. Not bad for a homophone.

Correcting a Castely Mistake

Although confusing one word with another may sometimes be educational, confusing the Indian caste system with the four-class social system described in India’s ancient Vedic literatures is a serious blunder.

How so? Because the Vedic literatures do not advocate a hereditary class system. Rather, they point out that in every civilized human society there is a natural division of intellectuals, administrators, businessmen, and laborers. Whether we look at ancient India or at modern Western nations, the four general occupational divisions are present, functioning within society like parts of the same body. They exist whether we recognize them or not.

The intellectual class, composed of scholars, scientists, and members of all the learned professions, is the head of the social body, providing advice, direction, and knowledge. The administrative class is the arms, organizing, policing, and protecting. The mercantile class is the stomach nourishing the body through agriculture and trade. And the working class is the legs, serving the other classes with skilled and unskilled labor.

Service, however, is the dharma, or inherent function, of all classes, not just of the workers. As the parts of our physical body cooperate for the well-being of the entire body, so each class serves society with its particular skills and capacities. Although we might correctly assert that the head is the most important part of any body, no sensible person cares only for his head. As I lay on the ground beside home plate on that spring evening, my throbbing knee had my full attention, and it continued to get special treatment until I was back on my feet and fit to play again. Pain in any part of the body draws the immediate attention of the total person. Similarly, disturbance in any of the four classes should draw the concern of the entire social body, beginning with the head.

From the Bhagavad-gita we learn that the four-class social system, known as varnasrama, exists in all places and at all times because it was created by Lord Krsna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead, simultaneous with the creation of human society itself. Just as many theists hold that the design of the universe indicates a supreme designer and creator, so proponents of varnasrama point to the existence of a universal four-class social structure throughout history. This, they say, confirms Krsna’s statement that these classes are not chance occurrences but His doing.

Krsna also, informs us in the Gita that the two primary criteria for identifying the four social classes are not birth and family tradition but qualification and work. For example, in our everyday experience a person who knows how to build with wood (qualification) and who regularly uses this skill to, say, construct houses (work) is known as a carpenter. That is his occupational service to society, his dharma. Similarly, a person who knows medical science and spends his time trying to cure diseases or to repair the torn ligaments of backyard athletes is called a doctor. Continuing in this way, we could survey any society and define innumerable classes simply by discovering the qualifications and activities required to fulfill particular social functions—banker, baker, candlestick maker, baseball player, and so on.

Easy enough. And nothing so very new. The unique contribution of the Gita and other Vedic literature is, first of all, to point out the four general occupational categories and, secondly, to recommend standards of ideal behavior for each category. The essence of all these ideal standards is that every human being should become self-realized by devoting his occupational skill to the service of Krsna, or God. Devotional service to Lord Krsna immediately raises the devotee to the transcendental platform, above the bodily conception of the self. In ordinary consciousness we think, “I am this body. I am a carpenter, a doctor, an athlete, a man, a woman. I am young, or I am old. I am Hindu, Muslim, Christian.” But in devotional consciousness, or Krsna consciousness, we are able to grasp the Gita’s instruction that we are not the temporary body but are the eternal individual souls within the body, and that as such we are eternal parts of Lord Krsna, the supreme soul.

While our ordinary dharma may be to serve society with our occupational skills, our sanatana (eternal) dharma begins with using those same skills to directly satisfy the Supreme Lord. In the Gita Krsna advises, “Whatever you do, whatever you eat, whatever you offer or give way, and whatever austerities you perform—do that as an offering to Me.” Lord Krsna has specifically designed the varnasrama social system so that each individual can easily reestablish his or her eternal relationship with God and so that society as a whole, united in the common cause of devotional service, may function as one healthy body, fulfilling both its material and spiritual needs.

Proper use of the varnasrama divisions results neither in divisiveness nor in occupational immobility, but in a oneness of purpose and in the full exercise of individual skills for Krsna’s pleasure. In varnasrama, everyone has not merely an occupation or job but a calling in devotional service.

Without devotees and devotional service, the natural four-class social body has no life.

Hereditary Baseball And Other Legacies

Whether we’re talking of class distinction or of spiritual elevation, birth counts for little in the Vedic scheme of things. Nevertheless, Vedic authorities acknowledge that family tradition may strongly influence one’s choice of occupation. After all, it’s not unusual for a boy to aspire to be “just like Daddy” and to take advantage of his father’s experience in a particular field.

A baseball field, for example. Of the 1,147 men who played in the major leagues during the 1980 season, 47 (4 percent) were the sons of former major-league players. If you consider that millions of young men were competing for those major-league spots, it turns out that sons of baseball players are fifty times more likely than others to play pro ball. Of all major American sports, baseball has the highest percentage of father-son pairs. Hockey and football are next, with basketball in last place. (“The Natural Choice,” Psychology Today, August 1985.)

Caste baseball? Hardly. Not if ninety-six percent of all major leaguers are first generation. Moreover, sports buffs say that the high degree of career following in baseball is due to a legacy of knowledge and experience, not to genes. Baseball sons can tag along with dad to spring training, hang around the ballpark and dugout, rub shoulders with their father’s friends, and thus begin to refine their own abilities at an early age. Inherited physical characteristics, experts claim, are far less important than knowledge and training. And, I can add, knowledge and training are simply means of passing along genuine qualifications, because no matter what else you have going for you, you’ll never make the majors if you can’t hit or throw a baseball, or if you rarely play the game. The same goes for any occupation. We’re not going to allow a surgeon’s son to operate on us simply out of deference to his father. When I injured my knee on that fateful night in 1967, I went to our long-time family doctor. As the Gita confirms, qualification and work are what count most.

The legacy of Vedic knowledge directs the members of society, regardless of occupation or class, to devote themselves to the Personality of Godhead, thus qualifying themselves to purely love Him. Family heritage, public and private education, and cultural tradition are only incidental. In any setting, devotion imbues an individual with transcendental qualities.

Within this overall devotional context, however, the Vedic literature recommends standards of behavior for each social class.

Most importantly, the Gita enjoins intellectuals to cultivate, among other things, peacefulness, self-control, austerity, and wisdom. Even a schoolboy doing his homework, what to speak of a scholar or scientist engaged in research work, requires a peaceful, controlled mind. Beyond this, a learned man should know the difference between the self and the body and should therefore understand that to feverishly gratify the body, as lower animals do, is not the purpose of human life. Animals are interested only in eating, sleeping, mating, and defending. While human beings also must fulfill these needs, the primary necessity of human society is self-realization. Without realization of the self and God, a human being’s behavior can be no better than an animal’s. As the brains of the social body, the intellectual class has a responsibility to keep human society human.

When the social brain is not self-controlled and self-realized, the rest of the social body, following suit, goes whole hog for sense gratification. This is just the opposite of devotional service. In a society centered on devotional service, everyone works cooperatively to satisfy Krsna, whereas in a whole-hog society it’s ultimately every man for himself, every nation for itself, at the trough of material enjoyment. The conflicts human society faces today—between individuals, between classes, between nations—are whole-hog conflicts stemming from ignorance of the eternal soul and from the consequent animalistic greed to dominate the resources of this planet.

A four-class varnasrama society headed by a class of learned, self-controlled individuals has the potential to transform whole hogs into self-realized souls and devotees of the Supreme Person. This would eliminate, or greatly reduce, the present level of conflict.

Leave a Reply