“Krsna assures us in the Bhagavad-gita that if we want to live there He will make the arrangements. But first we must demonstrate that we are ready.”

by Nagaraja Dasa

Though the spiritual world is the abode of the highest pleasure, hardly anyone wants to go there. We say we’d like to go, and we may think we are going, but our actions speak differently. Either we don’t fully believe in a spiritual world, or the information we have about it hasn’t inspired us to act in a way that will get us there.

Most of us, having only scanty information of the spiritual world, imagine a place where angels float on clouds and play harps and trumpets all day—a boring existence when compared to our present life, with its friendships, family relations, fancy cars, nightclubs, restaurants, and Sunday afternoon football. Without these things how can heaven be enjoyable? We even joke that hell would be better than heaven, because all our friends would be there. Fortunately, from the Srimad-Bhagavatam and other Vedic literature we get a much clearer, more inviting picture of heaven.

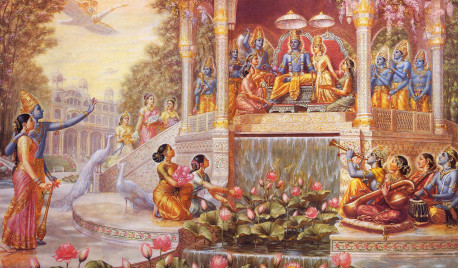

The spiritual world is not the creation of someone’s imagination. It is God’s eternal abode. Because God is a person, He has His own abode, called Vaikuntha in Sanskrit, meaning “devoid of anxiety.” Being God’s home, Vaikuntha possesses unlimited beauty and opulence. It’s not a boring place. It is the realm of the original, spiritual forms of everything we find in the material world.

In other words, it’s full of variety: birds, animals, forests, lakes, cities, airplanes, skyscrapers—everything. But they’re all spiritual.

For example, in the many forests of Vaikuntha, the trees—being fully conscious living beings like everything else there—supply everything the residents desire. Cintamani, a spiritual wish-fulfilling gem, serves as construction material in Vaikuntha. The residents, unalloyed devotees of God, possess spiritual bodies that never become diseased, grow old, or die. Free from the frustrations and anxieties of material life, these eternally liberated souls enjoy unending happiness.

We conditioned souls, habituated to the dualities of happiness and distress in the material world, cannot conceive of the pleasure available to the inhabitants of Vaikuntha. Material pleasures come only from the interaction of our senses with the sense objects (sound, form, touch, taste, and smell). Since the senses and their objects are limited and temporary, the pleasures derived from their interaction must also be limited and temporary—and therefore not really satisfying to the self, which is eternal.

Further analysis of material pleasures shows that they give only respite from our normally distressful condition. The material world, by its very nature, gives us distress: our own bodies and minds trouble us; business competitors, government officials, foreign governments, insects, dogs, and all sorts of other creatures harass us; and excessive heat, excessive cold, hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes, and other unconquerable forces of nature torment us. No one is exempt from these miseries. They constantly attack, and if we can momentarily overcome them—or even forget about them—we think ourselves happy.

Spiritual pleasure is in another category altogether. In the spiritual world everyone derives pure happiness by serving God, Krsna. Such service is the innate function of the soul. Once one tastes the happiness derived from that service, one automatically spurns even the highest material pleasure. A great devotee has explained that even one drop of pleasure obtained from devotional service to Krsna far exceeds an ocean of material pleasure. Thus Vaikuntha, which is permeated by service to Krsna, is the abode of unlimited pleasure.

Because we all want pleasure, when we hear from authorized sources that Vaikuntha offers it unlimitedly, we should naturally want to go there. And we can if we want to. In fact, we were all there originally, but we left. Why? Because we didn’t fit in.

To live in Vaikuntha, we must be like its other inhabitants. Because of their full devotion to God, they never consider their own welfare; selfish desires do not exist there. The devotees serve Krsna and each other in total selflessness. Were we to enter Vaikuntha to fulfill our own desires, we would create a disturbance to the inhabitants, who are absorbed in satisfying Krsna’s desires. So even though we may claim that we want to go to the kingdom of God, how many of us are ready to live as its residents do?

As evidenced by our deeds in this world, most of us would rather live some other way. We’d rather be selfish than selfless. We’d rather go to Las Vegas for the casinos or to the Bahamas for the sun and surf. Travel agents sell plenty of tickets to these places. But few people want to go where everyone selflessly serves the Supreme Personality of Godhead without personal interests. Krsna assures us in Bhagavad-gita that if we want to live there He will make the arrangements. But first we must demonstrate that we are ready.

We’re in the material world because we’re not ready; we want to enjoy the kingdom of God without God. Krsna created us to enjoy with Him. That’s our eternal service, and it’s blissful—it’s ecstatic! But we don’t want it. We don’t want to serve Krsna, because we covet His position. We want to enjoy here. Our original, pure consciousness—our Krsna consciousness—is infected with the impure desire to enjoy the material world without Krsna.

Without overcoming this disease of material consciousness, we’ll never want to go back to Vaikuntha. But if we sincerely desire eternal happiness, we must go back there. We’ll need to recover our spiritual health.

That means we’ll need a guru, a spiritual doctor who is going to ask us to do things we may not like. Patients usually dislike their medicine, but if they take their medicine and follow the regimen the qualified doctor prescribes, they’ll be cured.

Similarly, the spiritual master, guided by scripture, prescribes the activities—which, like medicine, may sometimes appear distasteful—that will restore our original, healthy condition. If, on the other hand, we try without proper guidance to enter God’s spiritual kingdom, we’ll be in a precarious position because we have not properly qualified ourselves.

For example, many people think they are leading a good life and will go to the kingdom of God after death. They feel no need to accept a spiritual master or the scriptures. They have their own conception of what “good” is. Certainly we may try to be good and hope God will grant us entrance into His abode after death. But what happens if our idea of goodness is inaccurate? What happens if it falls short of the mark? According to Bhagavad-gita and Srimad-Bhagavatam, the standard of goodness required of the inhabitants of Vaikuntha far exceeds the characteristic piety of good people in this world.

Philosophers have long debated whether there exists an absolute standard of goodness. Nowadays, people tend to favor the idea that goodness is relative to the individual, as the common expression “Whatever is right for you is all right” indicates. But what I think is right and what you think is right are not necessarily the same thing.

It’s reasonable and practical, therefore, to accept a definition of goodness from an authority. For example, we don’t run society on the premise that everyone is right. Rather, our lawmakers set up standards of acceptable behavior for those who want to enjoy the benefits of living in society. Then, even if a citizen doesn’t like the laws, he must either submit to them or risk punishment; they are not relative.

Similarly, God makes His laws, and we’re liable for punishment if we violate them—knowingly or unknowingly. This may seem unfair, but the same principle applies in the state: ignorance of the law is no excuse. To live in the state we must know its laws; to live in this world, which God created, we must know His laws. As human beings, with higher intelligence than the animals, we must accept that responsibility.

Fortunately, we can easily find out God’s laws, His standards of goodness, because the scriptures reveal them. So we should not reject the scriptures and invent our own religious path. As the Srimad-Bhagavatam states, dharmam tu saksad bhagavat-pranitam: God Himself enunciates religious principles. Religion essentially means God’s method for us to approach Him. Since we are in the subordinate position (He knows us but we don’t know Him), we must accept His direction on how to approach Him. That acceptance is the symptom of true goodness.

So if we really want to be good, if we really want to go to heaven, then we ought to let our actions speak the same as our words. That is the price for going back to the kingdom of God.

Notes from the Editor

Leave a Reply