by Dr. Diana L. Eck

to begin, a deeply significant existential dialogue took place between the warrior

Arjuna and Krsna, the Supreme Lord, who had manifested Himself as Arjuna’s charioteer.

Dr. Diana L. Eck is Assistant Professor of Hindu Religion in the Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies and the Comparative Study of Religion at Harvard University.

The Krsna consciousness movement is part of an important and distinctive tradition of devotional faith, the Gaudiya Vaisnava tradition, which began in the sixteenth century with the great saint Sri Caitanya, but which participates in a much older movement of devotion dating back to at least the second century B.C.

This devotional faith is called bhakti, which means devotion to God or the love of God. The word bhakti comes from a Sanskrit root which means “to love, to be devoted, to share.” Bhakti expresses the relationship between human beings and the Lord. It is a relationship of shared being and of mutual love.

The bhakti tradition found a full expression in the ancient Bhagavad-gita, “The Song of the Lord.” The Lord is Krsna, the Supreme Lord, who manifested Himself as the charioteer of the warrior Arjuna in the ancient era of the Mahabharata war. The Bhagavad-gita is the dialogue of Krsna and Arjuna at the edge of the Battlefield of Dharma (Right; Duty; Sacred Order) just as the battle is about to begin. It is an existential dialogue on some of the most deeply significant human questions, raised in this dramatic limit-situation: What is human life? What is transcendence? How can one be actively engaged in the world without being ensnared by it?

Krsna gradually reveals Himself to Arjuna as teacher, as friend, and finally as Lord. The Gita has been heard and told and cherished by generations of Hindus, who have seen Krsna as the Supreme Godhead: one who is utterly and awesomely transcendent and who is, at the same time, personal, loving, and intimately related to human beings.

Like the New Testament, the Bhagavad-gita is a gently revolutionary treatise. It picks up and redefines many of the major terms of the ancient Vedic ritual tradition, making religious life accessible and meaningful not only to the elite few—the brahmana priests, the gurus, yogis, and monks—but also to the common people in the context of their ordinary lives of relationships and duties.

What is sacrifice? It is not the complicated and expensive ritual fire sacrifice described at length in the ancient scriptures and performed infrequently by dozens of priests. Rather, all of one’s ordinary actions, done in an attitude of surrender to God, can be called “sacrifice:’

What is renunciation? It is not leaving the world behind to become a wandering monk or a hermit. Rather, it is active participation in the affairs of the world, renouncing only what is hardest to renounce: egotistical attachment to the fruits of one’s labors.

What is worship? It is not elaborate ritual which only a few can afford, but simple offerings to God, made with a pure heart. As Krsna explains to Arjuna: “Whoever offers to Me a leaf, a flower, a fruit, or water with devotion [bhakti], that person’s offering of love made with a pure heart do I accept.” (Bg. 9.26)

What is yoga? It is discipline. That to which one “yokes” oneself is one’s yoga. It is not only the spiritual discipline of those adepts who seek liberating wisdom (jnana-yoga). It is also the discipline of action without attachment to the personal rewards of action (karma-yoga). And it is also the discipline of devotion to the Lord in all one’s activities (bhakti-yoga).

Who is the yogi? Who is the priest? Not just the privileged few may follow the path of yoga or make acceptable offerings in the temple. Everyone, men and women, high caste and low, may be a yogi of devotion or may offer the simple fruits of action to the Lord.

Among the many religious ideas which the Gita shapes for the later tradition, bhakti is one of the most significant: the love of God which gives life and meaning to all one does—ritual, spiritual discipline, the search for truth, and ethical action.

The tradition of devotional piety that began in India with the Gita is long, varied, and rich. The life of the incarnate’ Lord Krsna is told in some of the great scriptures, particularly the Bhagavata Purana. He was born of a royal family—and rescued at birth from His uncle, the wicked king Kamsa, who wanted to kill the baby Krsna.

He grew up in the care of foster parents in the village of Vrndavana in rural north India. In. His life among these simple villagers, Krsna’s devotees have discovered meaningful paradigms for the human-divine relationship. Krsna was the child who grew up in their midst, and people loved the child Krsna with the spontaneous love of parents who delight in the playful exuberance of their children. Krsna was the heroic youth who conquered many a demon and protected the people of the land of Vraja. His companions loved Him—with the trusting, admiring love of friend for friend. To the young women of Vrndavana Krsna was the enchanting lover. Here one sees one of the most dramatic paradigms of human-divine love: the risking, serving, fervent, and sometimes anguished love of lover for beloved. Krsna and Radha are the divine pair, lover and beloved.

One of the most vigorous and vibrant periods of devotional piety on the Indian subcontinent began about five hundred years ago, when a new wave of this ancient bhakti tradition broke across north India as virtually a Protestant Reformation of the Hindu tradition. The love of Krsna was an important part of this movement, which produced a burst of devotional poetry, not in the Sanskrit of the elite, but in the vernacular languages of the people. In their songs and hymns these poets repeated many of the themes of the Gita: the supremacy of devotional faith rather than ritual; the affirmation of human equality rather than hierarchy; the importance of simple acts of praise—making offerings of flowers or singing the name of the Lord.

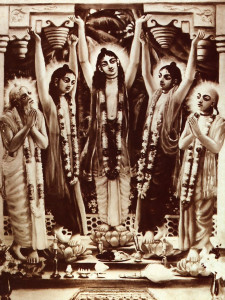

There were many poets, saints, and theologians who contributed to this era of exuberant devotion. Among them was the Bengali spiritual leader Sri Caitanya, who may be called the founder of the Hare Krsna movement. He was born in Bengal in 1486 and at a young age became an adept Sanskrit scholar. In 1508 on a pilgrimage to Gaya, he encountered a teacher of the devotional Vaisnava school named Isvara Puri. From this time on, he gave himself fully to the devotional worship of Krsna, popularizing and developing a form of worship called kirtana, the chanting and singing of the holy names of the Lord to the accompaniment of small brass hand cymbals and long cylindrical drums.

Sri Caitanya traveled throughout India and attracted many followers. He made one pilgrimage to the heart of the Vaisnava South, and according to his biographers he left the entire South chanting the name of Krsna. More important to the Caitanya movement, however, were his travels in the North, where he is said to have converted great nondualist philosophers as well as some of the world-renouncing sannyasis of Banaras to the love of Krsna.

Caitanya’s devotion to Krsna was both intense and magnetic. According to his immediate followers, Caitanya revealed himself as Krsna and Krsna’s beloved Radha manifest together in one body.

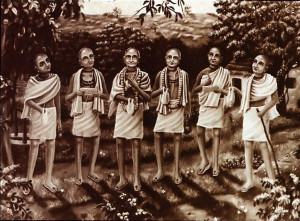

Sri Caitanya himself left only eight written verses. After he passed away, however, he was followed by a group of six inspired disciples and scholars called Gosvamis who settled in Krsna’s ancient homeland of Vrndavana and contributed a tremendously rich body of literature to the emerging Gaudiya Vaisnava tradition. Among them, Sanatana Gosvami wrote the famous Hari-bhakti-vilasa, a manual of ritual still utilized by the Hare Krsna movement. His brother Rupa Gosvami wrote one of the principal theological works of the movement, the Bhakti-rasamrta-sindhu, translated into English by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada as The Nectar of Devotion. Rupa Gosvami, the author of Sat-sandarbha; was the chief philosopher of the movement. A somewhat younger contemporary was Krsnadasa Kaviraja, who, at the request of the Gosvamis, wrote the biography of Sri Caitanya, the Caitanya-caritamrta, in Bengali.

From this first generation of disciples both in Vrndavana and in Bengal, the great teachers of this devotional tradition emerged, one after another, passing their insight from one generation to the next. They have followed in succession to the present day, and Vrndavana continues to be the spiritual heart of this bhakti tradition.

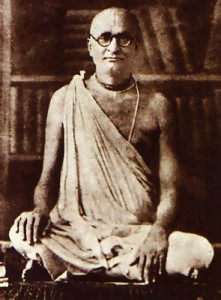

In 1933 one of the leaders of the Gaudiya Vaisnava movement, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Gosvami, initiated a new disciple: A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, whose special task was to bring the message of krsna-bhakti to the English-speaking world. In 1944, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami began to publish in Calcutta an English semimonthly magazine called Back to Godhead, which is published in the United States today under the same name. During the fifties he retired to Vrndavana, where he lived a very simple life in the temple of Radha-Damodara and began to translate into English the voluminous Bhagavata Purana. In 1965, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami came to the United States, arriving by freighter, with little money and no contacts. In time, with difficulty, he established the first Krsna temple in the United States, a Second Avenue storefront on the Lower East Side in New York. Before long, one could hear the name of Krsna in Tompkins Square Park or on Fifth Avenue. Within a decade the International Society for Krishna Consciousness—the American strand of the Gaudiya Vaisnava tradition—spread to most major American cities. It became known by the very words with which the saint Caitanya praised the Lord some five hundred years ago: “Hare Krsna!” “Praise Krsna!”

Among the recent projects of those who have devoted themselves to Krsna is the establishment of a farming community in the hills of West Virginia named after the homeland of Krsna—New Vrndavana. Meanwhile, in the original Vrndavana, the worship of Krsna flourishes, and the new Krsna-Balarama temple, built by the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, has become one of the favorites of Hindu pilgrims to the holy land of Krsna.

In the summer of 1978 while I was doing my own research in north India, I was approached by a number of Hindus who assumed, because I wore a sari and spoke Hindi, that I was a Hare Krsna devotee. Without exception they praised the work of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness in India, both in Vrndavana and in the birthplace of Caitanya at Mayapur in Bengal. I remember especially one old woman who came up to me in a temple in Banaras, and touched my feet in a gesture of respect, and said to me in Hindi, “The temple you have built to Lord Krsna in Vrndavana is splendid, so splendid, and I want to thank you.”

Surely the greatest affirmation of the authenticity and significance of the Hare Krsna movement has come from Hindus themselves. In Boston the ISKCON temple has become a gathering place for many of the Indians who live here as professional people or as students. There on Commonwealth Avenue, together with American devotees, they worship Krsna and celebrate the great festivals of the Hindu year. And in Vrndavana, Hindus crowd into the new Krsna-Balarama temple and sing “Hare Krsna” with those young Americans who have become new participants in their ancient tradition.

Leave a Reply