The Vedic science of rasas (relationships)

reveals to us the many ways of loving God.

by Mathuresa Dasa

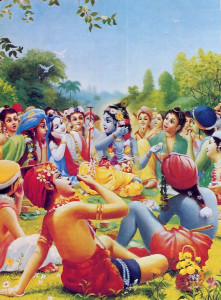

loving relationships. He enjoys lunching with His friends

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.”

One, two, three, four, five.

Poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning had something else in mind when she penned her beatific “How do I love thee?” question, but the Vedic literature of ancient India, highly poetic itself, answers that there are primarily five ways that an “I” and a “thee” can love each other: (1) in a mood of reverence, (2) in a mood of service, (3) in a mood of friendship, (4) in a mood of parental, or protective, affection, and (5) in a mood of conjugal affection.

Browning fans might think these five categories constitute a relatively cold analysis of love’s ways. Even a cold analyst might take exception. What would Sigmund Freud have to say? Does his Oedipus complex fit into the parental mood or the conjugal mood, or not fit at all? And how about Carl Jung? If these five categories exist, then why in his extensive research in the fields of personality and self-discovery did he never discover them? Erich Fromm does list five types of love in his book The Art of Loving, but they differ from the Vedic types.

Nevertheless, the five loving moods, while not listed in the writings of modern poets and psychoanalysis, are easy to recognize in our own everyday lives. The Sanskrit term for these moods is rasa, a word that also carries the connotations of “relationship” and “taste.” We taste loving relationships in these five rasas. For clarification, let us count the ways again, briefly elaborating on each rasa.

1. Reverence. We revere, or stand in awe of, persons we consider greater than ourselves—a politician, a famous artist or athlete, a successful businessman. Knowledge of someone’s achievements and social position is an important factor in invoking our respect. Reverence is sometimes called the neutral rasa because it involves only passive admiration, not an active exchange with the revered person. In the strictest sense, therefore, it is not a loving mood, although it may foster love.

2. Loving service. When reverence intensifies, it inspires us to perform service, which is the next rasa. Out of admiration for a political candidate, for example, we may help in his election campaign, or at least vote for him. Our feeling of reverence is still there, but we act on it. Not only in the political field but in other social situations as well, the voluntary rendering of service develops from a foreground of reverence and respect. Service rendered strictly for money, or involuntarily out of fear, is not love.

3. Friendship. When the rasa of service intensifies, it may develop into friendship. Again the example of a politician: through prolonged service in his or her campaign, you may come to know the candidate personally, and the candidate, instead of treating you like a servant, may begin to confide in you as a friend. The rasa of friendship contains the previous two rasas, but since friendship involves equality and familiarity, the rasa of awe and reverence diminishes markedly. Your friend’s awe-inspiring credentials are not as important as his individual qualities.

4. Parental affection. Intensify friendship and add to it a feeling of protective superiority toward the object of your affection, and you have the parental rasa. Parenthood ordinarily denotes the relationship between a biological father and mother and their children. But we cannot confine the parental rasa to biological kin. Men and women often show parental affection for others’ children or for each other.

5. Conjugal affection. This topmost rasa includes the previous four. In addition to respect, service, friendship, and protective affection, conjugal lovers enjoy erotic exchanges as well as feelings of exclusive intimacy.

So there it is. Are these five rasas not apparent in our daily affairs? Vedic authorities assert that any other categories of love we might perceive are merely subdivisions of these.

The concept of rasa encompasses not just loving relationships but unloving ones as well. When the five primary rasas are disturbed, or when they are absent altogether, seven secondary rasas take over.

Aach! More counting of the ways? Yes, just one last tally. The secondary rasas are: (1) anger, (2) wonder, (3) comedy, (4) chivalry, (5) mercy, (6) dread, and (7) ghastliness. Secondary rasas vary in intensity—from the dread of a visit to the dentist to the horror of losing a child, parent, or other loved one. The story of Romeo and Juliet is one famous example of a secondary rasa, ghastliness, resulting from the disruption of a primary rasa, conjugal love. These twelve rasas, five primary and seven secondary, constitute the sum total of personal relationships in every society. Life is an ocean of rasa.

The Vedic science of rasa provides an interesting and useful analytical framework for the study of interpersonal psychology. We could discuss current high divorce rates, for example, in terms of the negative effect that secondary rasas have on family members when the primary marital and parental relationships are broken. Or we could advocate friendly relationships between nations, since in the absence of friendship dreadful and ghastly wars are likely. But it is also interesting and far more useful to understand that the great self-realized authors of the Vedic literature have given us the science of rasa first and foremost to help us reawaken our eternal loving relationship with the Supreme Personality of Godhead, Lord Krishna.

Krishna is no less a person than we are, which means that He can also relate to others in twelve rasas. In fact, He is the original person, the primeval cause of all causes. The conception of God as an enjoyer of rasa does not originate in the human imagination. No. Krishna is our origin. We reflect His qualities. Although God is great and we are small, we are qualitatively equal to Him. Therefore, just as you can know something of the Atlantic Ocean by tasting one drop of ocean water, you can know something of Krishna by observing yourself.

Observe myself? How? By looking in the mirror?

Not exactly. In the Bhagavad-gita Krishna explains that the self, the individual person, is not the physical body but an eternal spirit soul dwelling in the body. The body is temporary clothing covering the eternal soul. Not only in the human body but in every living body in all species of life—the plants, aquatics, insects, birds, beasts, and human beings—there is an individual soul. The proof of the soul’s presence is that even the animals exchange rasa, showing affection for mates, children, parents, and so on. So to observe the self means to observe not the body but how a living entity exchanges rasas.

In general we see that rasas are exchanged only with members of the same species. It is sometimes said that the dog is man’s best friend, but there are in fact many obstacles to a meaningful exchange of rasa between a human being and a dog, or between a human being and any other species. We naturally restrict “counting of the ways” to our own kind. Man to man. Dog to dog. Salamander to salamander.

On the spiritual platform, however, every person, whatever his temporary bodily covering, is of the same quality, the same species, as the Supreme Personality of Godhead, Lord Krishna. Exchange of rasa with Krishna is therefore natural for everyone. Most religious traditions teach us to respect God as the all-great, all-powerful, all-knowing Supreme, and to serve Him in the mood of awe and reverence. This is certainly correct, but we overlook His true greatness and power if we ignore that He can also relate to others in the higher rasas of friendship, parenthood, and conjugal love. The Narada-pancaratra clearly states that pure love of God means to completely transfer our affection to the Supreme Person and to completely repose all sense of kinship in Him. The pure devotee takes Krishna as everything—master, friend, child, lover—and relates affectionately to everyone else as fellow servants of Krishna.

Mundane affairs in this temporary physical world appear more interesting to us than religious or spiritual pursuits precisely because mundane affairs hold the promise of varieties of personal exchanges in each of the twelve rasas, whereas religious advancement, we falsely believe, does not. Without at least some preliminary knowledge of the completeness of God’s personality, of His ability to exchange rasa, it is difficult, if not impossible, even to revere Him. How can you revere a nonentity? Ignorant of the Vedic science of Krishna consciousness, people gradually take to agnosticism, atheism, and lip-service-ism.

The Vedic literature doesn’t recommend that we imagine ourselves to be intimate friends of the Supreme Person. Krishna is certainly able to share friendship and parental and conjugal affection with us, but to comprehend the spiritual nature of loving affairs with Krishna we must first fully understand that we are infinitesimal spirit souls and that Krishna is the Supreme Soul. Until we are acquainted with our non-physical, spiritual identity as members of Krishna’s “species,” reverently recognizing Krishna’s supreme, all-powerful position, we cannot even begin to experience an exchange of rasa with Him. Intimacy with the Lord, if we desire it, is possible only after we qualify ourselves.

It is also a mistake to think that Krishna’s loving affairs are exactly like the affairs we experience in the material world. There are similarities, but material loving affairs are temporary and therefore bound to disappoint us, whereas spiritual rasa is eternal, pure, unlimited, and ever-increasingly satisfying. In particular, we should not equate Krishna’s conjugal affairs, which are sometimes graphically depicted in books on Eastern religion, with the affairs of ordinary, or even extraordinary, men and women. Again, the two appear similar, but there is a gulf of difference.

The affairs of men and women on this tiny planet do not interest Krishna, the all-powerful creator and maintainer of millions of universes. Even Krishna’s confidential devotees, who glorify His pastimes of conjugal love, have no attraction for material love affairs. Lord Caitanya, who inaugurated the modern Krishna consciousness movement five hundred years ago, taught that there is no better worship of Krishna than that displayed by the damsels of Vraja, who worshiped Him in conjugal love. Yet Lord Caitanya was a strict renunciant and, although not disrespectful toward women, avoided even distant association with them. Conjugal love of Krishna is therefore not the conjugal love we know of in the material world. The material is a perverted reflection of the spiritual.

Accompanied by His confidential devotees, Krishna occasionally visits the material world, appearing in human society to display His transcendental pastimes and demonstrate to the embodied souls, who are absorbed in temporary loves, that He is Rasaraja, the king of loving affairs. He thus invites us to reawaken our eternal spiritual rasa with Him. Pure devotees of Krishna have recorded His earthly pastimes in epic works such as the Mahabharata (of which the Gita is one chapter), the Srimad-Bhagavatam, and the Ramayana. Through these great literatures one can relish the Lord’s pastimes with His devotees, learn the art and science of devotion, and gradually rise to the pure devotional platform.

Unfortunately, when Krishna mercifully appears, many foolish people mistake Him for an ordinary human being. They discount His superhuman pastimes or take them for myths and ignore the Vedic teachings, which establish beyond doubt His supreme dominion over all that be. We should not be misled by such confused persons, who cannot see beyond counting the paltry ways of love in this material world; instead we should take advantage of Krishna’s mercy and help the ones we truly love to do the same.

Leave a Reply