Bhakti Flows West

Sri Caitanya’s Children in America

An Indian scholar and devotee traces out the roots of Krsna consciousness in India and assesses the significance of its spread to the West.

Reprinted by permission of Grove Press, Inc. Copyright 1983 by Steven Gelberg

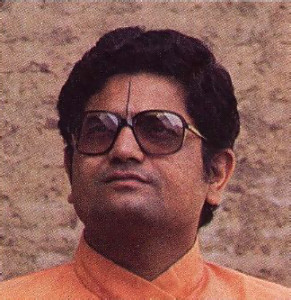

Shrivatsa Goswami belongs to a centuries-old lineage of Vaisnava priests connected with the famous temple of Radha-ramana in Vrndavana, India. He is the founder and director of the Shree Caitanya Prema Sansthana, a Vaisnava academic and cultural institute located in Vrndavana, and is a member of the Board of Editors of the Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies.

Shrivatsa Goswami belongs to a centuries-old lineage of Vaisnava priests connected with the famous temple of Radha-ramana in Vrndavana, India. He is the founder and director of the Shree Caitanya Prema Sansthana, a Vaisnava academic and cultural institute located in Vrndavana, and is a member of the Board of Editors of the Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies.

This is a condensation of an interview with Mr. Goswami conducted in Vrndavana in March, 1982. The full interview appears in Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna: Five Distinguished Scholars on the Krishna Movement in the West, a book recently published by Grove Press (paper, $7.95). The interviewer, and the book’s editor, is Steven J. Gelberg, a senior editor of the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust who is known within the Hare Krsna movement as Subhananda dasa.

Bhakti Tradition: Its Origins And Historical Development

Subhananda dasa: As we know, Krsna consciousness is rooted in the concept of bhakti, love of God, specifically krsna-bhakti, devotion to Lord Krsna, who is understood as the original and supreme form of Godhead. Let’s look at the concept of bhakti in a broad religious context. Bhakti usually is taken to be a subdivision of Hinduism—as a specific, localized aspect of Indian religious tradition. Should bhakti be viewed in this way—as a sectarian or culture-specific phenomenon—or can it be understood in broader, more universal terms?

Shrivatsa Goswami: If I could answer your question in one sentence, I would say that we can translate the term religion as bhakti. By religion, I mean the human quest for realization of the Divine. That quest presupposes a relation of man to God. In the religious quest one is, in one manner or another, trying to relate himself to God. That relating to God is itself bhakti, and the religious experience itself is bhakti. You can call it “Hindu bhakti” or “Christian bhakti” or “Islamic bhakti.” Any religious quest for God is, in essence, bhakti.

The highest mode of spiritual life is where no other motive remains except love. If you attain the sublime state of divine love, where there is no other guiding force, no other motive except love for the sake of love, then you have attained the realization of God as Bhagavan—Sri Krsna. That is the highest religious attainment.

Subhananda dasa: What about bhakti as a historical phenomenon? To what point in the religious history of India can we trace bhakti religion? As you know, many contemporary historians tend to describe bhakti tradition as an almost exclusively medieval phenomenon. Could you comment on that view?

Shrivatsa Goswami: Bhakti is an eternal human tendency; it is not merely some kind of historical movement arising out of peculiar social and cultural circumstances. Whenever or wherever there have been human beings, there has been bhakti in some form or another. Bhakti is like a river that takes different forms, sometimes widening, sometimes narrowing, and that moves this way and that way at different places and times. Sometimes it is fully manifested, and at other times it is eclipsed or subdued by various historical and cultural forces. It is like language. Sanskrit before Panini is different from Sanskrit after Panini. Words change, grammar and diction change. Fifteenth century English is not the same as twentieth century English, although the language is the same. So even language flows. It is a question of continuity and change. Bhakti is the same continuing stream, but it appears in different forms and degrees in different periods.

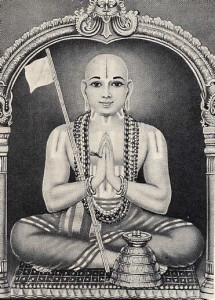

There are any number of scriptural, literary, architectural, and archeological evidences for the antiquity of bhakti. But if we view Indian religious history over the past two or three thousand years, it becomes apparent that bhakti tradition was strongest and most widespread in the medieval centuries—let’s say from the eleventh century onward, beginning with the appearance of the great Vaisnava acaryas [spiritual teachers] like Ramanuja and Madhva. Many ancient bhakti strains crystallized into the medieval bhakti movement.

Subhananda dasa: To what extent was the medieval bhakti movement a popular reaction against an elitist, brahminical Hinduism?

Shrivatsa Goswami: The bhakti movement can be seen in some sense as a revolt against the ritualistic “high” tradition, the brahminical, scholastic tradition. We have to bear in mind, however, that this kind of revolt was natural. Religion is a process, a historical process; it is never stagnant. What was good for the Vedic period was not necessarily good for the fifteenth century. The tradition had to be brought into the present. Metaphysical realities, religious concepts, are eternal. But those primeval concepts have to be worked out, from age to age, in the form of practical religious life. You need timely expressions of ancient tradition. In order to accomplish this, you have to constantly review your religious practices.

So, at this time, there was oppression from the brahminical ritualistic tradition. It had become overly ritualistic, intellectual, and exclusivistic. But with the revival of bhakti and the dispensing of ritualistic formality, God became, so to speak, more accessible and immediate. The bhakti movement was democratic. It provided, you might say, equal opportunity for all people to work out their salvation. That was not possible in the stagnant brahminical tradition. In this sense the bhakti movement was a great revolution. It opened the gates of salvation to everybody. This was the great and unique contribution of bhakti, religiously and sociologically.

Subhananda dasa: Shrivatsa, could you now describe the development of the bhakti movement—or conglomeration of bhakti movements—from roughly the eleventh to the eighteenth centuries? Who were the major figures and what were the important movements during this devotional renaissance?

Shrivatsa Goswami: The medieval bhakti movement took birth in South India with the Dravidian saints, the Alvars and so on. Then a little later, Ramanuja, the first systematic philosopher of bhakti, appeared in the Tamil country. He was the first major acarya to declare bhakti, aside from jnana [philosophical speculation], a legitimate path to realize God. After Ramanuja, the next great devotional thinker was Madhva, who was born in Karnataka at the end of the twelfth century. After that, the movement got a big boost from different saints who appeared throughout India, including Maharashtra, during the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries. These centuries were very crucial for the growth of the bhakti movement.

Subhananda dasa: What were some of the distinctive religious practices and forms of worship within the devotional movements?

Shrivatsa Goswami: In general, the bhakti movements attempted to spiritualize, to make sacred, ordinary worldly activities. Take eating, for example. Eating is a common human activity. Everybody eats. But the eating of food was transformed into a religious activity by first offering the food in devotion to the Lord. The food thus became sanctified as prasadam, the mercy of God. Aesthetic values were made religious. Poetry, art, dance, song, and drama: all were dedicated to glorifying God by depicting His divine form, attributes, and activities. Artistic pursuits all became saturated with bhakti. So the whole of human existence became refined into spiritual existence. The dichotomy between the phenomenal and the spiritual was broken down, or, rather, these two realms were brought closer together.

Subhananda dasa: What about nama-sankirtana, congregational chanting of the names of God? In the Caitanya movement, of course, nama-sankirtana was the principal form of worship. Was this also the case with other bhakti movements?

Shrivatsa Goswami: Nama-sankirtana was definitely widespread, and music has always definitely been an important part of Vaisnava traditions. Almost all of these saints wrote and sang songs and hymns and wandered from place to place singing and preaching. I would say that singing was the mode of worship. You could say it was a “musical revolution.”

The Caitanya Movement

(A.D . 1486 -1534)

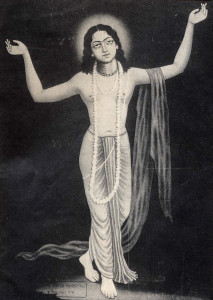

Subhananda dasa: Of all the individual bhakti movements that appeared during this era, none, perhaps, was as widespread as Caitanya’s krsna-bhakti movement, and none appears to have so successfully survived into the present. First of all, who was Sri Caitanya?

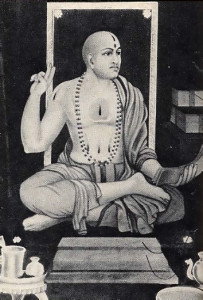

Shrivatsa Goswami: When we try to understand the personality of Caitanya, we can look at Him from many angles. If we wish to understand Him from a theological perspective, then we have to deal, first, with the concept of avatara [incarnation] in Indian philosophy. This concept is very basic to the religious history and life of India. You’re familiar with the theological importance of the concept of avatara, so we don’t need to speak about that in detail here, except to say that there are two worlds: the spiritual world and this material world, and for any religious purpose there has to be a point of contact, or a meeting ground, between the two. That contact or meeting ground is expressed through many concepts in Hinduism, such as avatara, sastra (scripture), mantra, and guru.

Caitanya was the Kali-yuga pavana-avatara, the supreme avatara of the age, the dual incarnation of Radha and Krsna who came to purify the world. In Indian theological matters, the pramana, or proof, for anything is scripture. The Srimad-Bhagavatam, being the scripture par excellence—the culmination of the scriptural tradition—gives proof about the avatar-hood of Caitanya. There are many direct and indirect references to Caitanya-avatara in scripture—references not only in works by Caitanya’s biographers but in much earlier texts, especially the Bhagavatam.

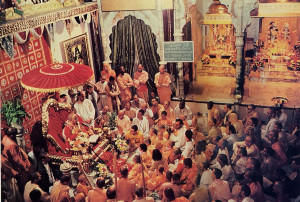

Caitanya’s movement actually started in the closed courtyard of Srivasa, in Navadvipa. Caitanya, Srivasa, Advaita Acarya, Nityananda, and several other Navadvipa residents who were all great devotees of Krsna would gather together and dance and chant, day and night, in the closed courtyard of Srivasa. Eventually, their spiritual ecstasy could not be confined to the courtyard of Srivasa. It burst out of the courtyard and into the streets of Navadvipa.

So, first the chanting was confined to the house of Srivasa, then it pervaded the town of Navadvipa, then it spread throughout the whole state of Bengal, and then it spread into Orissa and beyond. Wherever Caitanya went, nama-sankirtana spread like wildfire.

(16th-17th centuries A.D.)

Subhananda dasa: Some modern students of Hinduism claim that Sri Caitanya was always so engrossed in devotional fervor and mystical ecstasy that He didn’t get around to, or wasn’t able to, formulate a systematic philosophy or articulate it to others.

Shrivatsa Goswami: This is one of the modern misconceptions about Caitanya, put forward by people who possess a very superficial understanding of Caitanya and His tradition. The main reason that Caitanya’s role as philosopher and theologian is doubted is because Caitanya did not personally write out His system. From the traditional Indian point of view, it is not necessary for a religious or philosophical system to be written. The Vedas existed for thousands of years before they were compiled in written form. They were presented through oral tradition and transmitted from guru to disciple. In ancient India, people had the mental capacity for memorization and total recall of scripture. Oral transmission was the system of religious and philosophical education.

So, although Caitanya did not write philosophical treatises, He did evolve a philosophical and theological system, and He revealed it through lengthy discourses with Sarvabhauma Bhattacarya and Ramananda Raya, with Sanatana Gosvami in Benares, with Rupa Gosvami in Allahabad, and in shorter discussions in South India with Venkata Bhatta, the Tattvavadis [followers of Madhva], some Buddhist monks, and so on. All of these dialogues are recorded in Caitanya’s biographies. The six Gosvamis heard, gathered, assimilated, systematized, and then wrote Caitanya’s teachings in their many philosophical, theological, poetic, dramatic, and instructional writings.

So the whole Gaudiya Vaisnava system is based upon Caitanya’s teachings, which evolved from His own experience. You cannot isolate philosophical thought from personal experience. There can be no “neutral” philosophy, just as there can be no “neutral” religion. Philosophy must have its roots in experience. What we have to understand at this point is that what we translate as “philosophy” is actually darsana. Darsana literally means “seeing.” According to Sanskrit etymology, we can define darsana in two ways: the act, itself, of seeing or that by which we see, the process by which we come to the point of seeing. So, philosophy is an experience, a “seeing,” an immediate realization, or direct encounter with something—and that something is ultimate reality, or God.

In the Western tradition, philosophy is a kind of armchair game having little to do directly with life or experience itself. Originally, this was not so. But as the philosophical systems evolved, philosophy moved away from its spiritual moorings. In the West, a philosophical system must be a systematic written treatment of a well-defined Weltanschauung, with logical treatises and so on.

But in Indian tradition it is the direct, intuitive experience that is primary and crucial. The Buddha did not write a single word. What teachings we have, we get only from his disciples; yet he has a very strong and well-developed philosophical system. It is the claim of spiritual experience that is important. One glimpse of Caitanya’s experience ignited a series of explosions, and those explosions were the writings of the Gosvamis.

Bhakti Abroad: Caitanya’s Children in America

Subhananda dasa: Shrivatsa, as a Caitanyaite and an observer of the Krsna consciousness movement, how do you view the significance, historical and cultural, of the spread of the Caitanya tradition to the West?

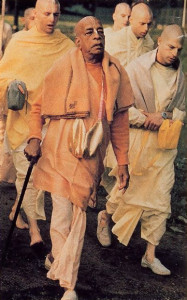

Shrivatsa Goswami: When I reflect on Srila Prabhupada’s achievement, I become sort of a Hindu chauvinist. It is a great political achievement.

Subhananda dasa: How is it a great political achievement?

Shrivatsa Goswami: In that Indian spiritual culture has been spread throughout the world. What the Muslims could do only by the tremendous sword, and the Christians could do only with great financial resources and state power, has been done by one solitary man, without any ill effects.

Subhananda dasa: It’s often taken for granted that Hinduism, in contradistinction to Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism, is not a missionary religion. Yet isn’t it a fact that Caitanya Vaisnavism has always been a missionary tradition? Didn’t Caitanya Mahaprabhu directly instruct His followers to spread Krsna consciousness?

Shrivatsa Goswami: Yes. Any truth is for spreading. Not only Caitanya, but look at Sankaracarya. What did he do? All his life he traveled throughout India and spread his message. The Buddha did the same. Ramanuja, Madhva—all the Vaisnava theologians and saints were missionaries like Caitanya. In addition to preaching Himself, Caitanya instructed His followers to preach the message of krsna-bhakti from door to door and from village to village. Caitanya said,

yare dekha, tare kaha ‘krsna’-upadesa

amara ajnaya guru hana tara’ ei desa

“Whomever you meet, teach him about Krsna. Become a guru and liberate everyone in this land.”

Subhananda dasa: Is there anything unique about ISKCON’s missionary activities in the West, in light of this Caitanyaite preaching tradition?

Shrivatsa Goswami: One significant difference between historical Caitanyaism and ISKCON is that you have to deal with people who are not even in the broad category of Hinduism. Historically, the Caitanyaites were preaching to people who were already Hindus, even Vaisnavas. Most of those to whom they preached were already worshiping Krsna or Visnu, and they even studied the same scriptures as the Caitanyaites. Their preaching was mostly a matter of “polishing.” But you ISKCON devotees have to deal with people who are completely “raw.” That is a big difference. Srila Prabhupada’s going to the West to preach krsna-bhakti was a very bold move. He was very courageous.

Srila Prabhupada also faced a unique twentieth-century situation in that materialism had become so predominant. In such a materialistic culture, what Prabhupada achieved was remarkable. He had remarkable results: he spread the spiritual message of Caitanya even in a culture that had no grounding in Hindu culture and that was so steeped in materialism.

Subhananda dasa: Why do you think he was so successful?

Shrivatsa Goswami: If you study the situation in detail, you have to take into account the American social and political situation, which might have created a favorable climate for his teachings. But these were auxiliary factors. They were not the primary factors. The primary factors that brought about this kind of revolution were the strong personal convictions and personality of Srila Prabhupada and the great spiritual philosophy he preached. These were unique. Krsna-bhakti is a universal phenomenon, and so it is only natural that it should travel throughout the entire world. And this long-awaited journey was made possible by Srila Prabhupada.

Subhananda dasa: Can you comment, Shrivatsa, on Srila Prabhupada’s choice of texts to translate and make available in the West?

Shrivatsa Goswami: There is no doubt that he made a wise selection of texts to translate and comment upon. As for the Srimad-Bhagavatam, we’ve already discussed its importance to some degree. The Bhagavatam is of central importance not only for the Caitanya-sampradaya [sect], but for the whole Vaisnava and Hindu tradition.

Subhananda dasa: The importance of the Bhagavad-gita is, of course, understood.

Shrivatsa Goswami: Yes, the importance of the Gita is already widely known. As for the Caitanya-caritamrta—as a student of Gaudiya Vaisnavism, when I consider the Caitanya-caritamrta I bow down to the genius of Krsnadasa Kaviraja, because he shows his mastery not only in presenting the life of Caitanya but in presenting a beautiful, consummate philosophical summary of all the works of the Gosvamis. In the Caitanya-caritamrta one can find brilliant crystallizations of philosophical treatises, theological treatises, aesthetics, and poetry from the works of the Gosvamis. He provides hundreds of quotes from the works of the Gosvamis. So, through the nectar of Caitanya’s life, Krsnadasa Kaviraja presents a full compendium of the Gaudiya Vaisnava tradition. Srila Prabhupada has done a great service for all Vaisnavas, as well as for scholars, by translating and commenting on Caitanya-caritamrta.

What is significant is that for the first time these devotional texts are being made so widely available. If these texts are not available, what effect will they have? Making these Vaisnava texts available is one of Srila Prabhupada’s greatest contributions. Apart from the masses, his books have also reached well into academic circles and have spurred academic interest in the Caitanya tradition. There’s no escaping that. That is another positive effect of his writings.

The significance of making these texts available is not merely academic or cultural; it is spiritual. Jnana, knowledge, is spread, proper doctrines are made known, people come closer to reality. All problems arise from ignorance. If ignorance is destroyed, all problems are solved. That’s why it is stated in so many philosophies, like that of Jiva Gosvami, that ignorance, ajnana, is the greatest enemy.

And that is the purpose of Lord and guru: to destroy ignorance. I don’t mean jnana and ajnana in the technical Sankarite sense, but in the broadest metaphysical sense. That ajnana, most fundamentally, is ignorance of the Lord, of Krsna. That is the greatest ajnana. If you don’t know Krsna, then how will you know anything? Krsna is everything; everything is related to Him. And by knowing Him, you come to love Him. If you don’t love Him, you will love this material world, which is duhkhalayam, a place of misery, and asasvatam, temporary. So, to spread knowledge, as Srila Prabhupada has, is to make a definite contribution toward human happiness.

Subhananda dasa: Unlike most interpreters of the Indian tradition, who in their writings have highlighted the theoretical, philosophical component of the tradition, Srila Prabhupada draws the reader into the experiential dimension of Vaisnava spirituality. Not only did he generate interest, but he actually transformed lives.

Shrivatsa Goswami: That is true. In the Indian tradition there is no clear dichotomy, as there generally is in the West, between the intellectual/religious sphere and the practical sphere of life. So what Srila Prabhupada did was more reflective of the Indian tradition. His approach was more natural. Religion is not a “subject”; it is not an academic discipline like physics or chemistry. When I was in America, I used to tell university people that in India there are no academic departments of religion, except those very recently begun by Christian missionaries. In America, there are divinity schools everywhere, but in a religious country like India there is no “Department of Religion.” Why is that? Because in traditional Indian culture, everything is religion.

Even linguistically, in Indian languages there is no separate word for “religion.” Religion is not a separate category. The mode of being is itself religious. Religious conceptions dominate and pervade all dimensions of human life: family, business, statecraft—everything. The human being is intrinsically religious: homo religious. Srila Prabhupada did not try to turn Vaisnava tradition into an intellectual curiosity. He presented the tradition as it is—a spiritual mode of existence. His practical, experiential approach to the Vaisnava texts was the proper approach.

Subhananda dasa: Do you think there is anything in the Western culturation or mentality that can significantly hinder the Western ISKCON devotees from attaining the highest spiritual goals?

Shrivatsa Goswami: I do not feel that the Western Vaisnavas are handicapped by their own cultural or ethnic backgrounds. There is nothing to prevent them from following on the path of Caitanya and achieving the highest goals. They are fully entitled to that through having adopted the Caitanya Vaisnava path and through having come under the guidance of Srila Prabhupada and the present gurus as well, if they are teaching truly according to the highest spiritual goals. The emphasis should always be on the purity of the philosophical and spiritual side of the tradition. The externalities ultimately are not so important. The emphasis should be on the spiritual side of the movement. This is the crucial thing.

Subhananda dasa: Ultimately, then, the real test of the authenticity of ISKCON is the spiritual authenticity of its members.

Shrivatsa Goswami: Yes, the criteria should be spiritual. The evidence of the legitimacy of the Hare Krsna movement is that it has established the Caitanya tradition in the West, in a part of the world where formerly it had not existed. The criterion of fidelity is how well it will be able to establish its authority in the West. The question of authenticity, or fidelity, doesn’t concern the Caitanyaites in India. The question doesn’t arise for us. It arises only in that place where the tradition has not yet been established.

Any new movement that arises—even if it arises within a familiar cultural background—will face opposition, as you see at the beginnings of the Caitanya movement in India. It faced very stiff opposition: intellectual, social, and political. Obstacles were faced by Caitanya Himself, what to speak of ISKCON.

So the real criteria of fidelity, or authenticity, of the Hare Krsna movement will be the faith, steadfastness, and total commitment of its members. Its religious and spiritual authenticity will be proved only by its strength. You may write a hundred books on the legitimacy and authoritativeness of the Hare Krsna movement, but that may not prove very much. But if there are ten devout Caitanyaites in the West, the movement is legitimate and authoritative. The number is insignificant. But the integrity, the sincerity, and the faithfulness of the devotees is the only proof, and sufficient proof, of the movement’s authenticity.

When, in the West, someone comes to know that I am a Caitanyaite, he immediately asks me what I think of ISKCON. It is a question that I have to deal with any number of times. I consistently answer with one remark: the strength of the movement is not that they’ve published and sold nearly a hundred million copies of the Hindu scriptures, or that they have magnificent temples throughout the world, or that they have attracted ten thousand or a hundred thousand devotees to the movement worldwide. But even if there is one sincere devotee in the movement, the movement is very significant and important. And I sincerely believe that in this movement there are many sincere devotees, some very sincere devotees. And because of their force the movement is existing. It is not surviving due to money or power. It is the spiritual power and the spiritual existence of those sincere devotees that is sustaining the movement. That is my strong belief.

Leave a Reply