Some parents of Krsna devotees say their son or daughter can no longer think.

Are these parents thinking clearly?

“People Are Talking”

Two Jewish mothers respond in opposite ways when their sons join the Hare Krsna movement.

When Steven Eisenberg left the Hare Krsna movement in 1979, it wasn’t by plan—at least not a plan of his own.

He had joined the movement in 1975 at the age of 22, and when he phoned his parents to tell them about it, their reaction, his mother says, was “hysteria.”

“We cried a lot. And we tried to find out about the Krsnas.”

Where did they go to learn more?

A Jewish rabbi sent them to a meeting about “cults” to hear someone who had been “deprogrammed.”

At this and other meetings, they were told that their son had been “brainwashed” and, as his mother puts it, “he would not have the capability of thinking for himself.”

“It was horrendous for us to comprehend it,” she says.

So they hired “deprogrammers” and after a few days captive with them in a hotel room Mr. Eisenberg was miraculously free of “mind control” and “able to think again.”

(An alternative explanation, more acceptable to impartial observers, is that “brainwashing” is a plea a family can use to explain why their son or daughter chooses a “deviant” way of life. And “deprogramming” is method, usually brutal, of putting pressure on a young person to get him to change his mind. After he gives in, speaking the party line lets him avoid responsibility for what he did and play the role his family now expects.)

On August 17, the rehabilitated Mr. Eisenberg and his mother appeared on a Philadelphia TV show. People Are Talking, to tell their story.

In the audience were Hare Krsna devotees and both supporters and opponents of the Hare Krsna movement.

Among the supporters was Mrs. Nannette Hoffman, artist, teacher, and mother of a Hare Krsna devotee.

When Mrs. Hoffman spoke her mind, a dramatic—and revealing—confrontation took place.

Mrs. Hoffman: I’m Nannette Hoffman, the mother of a Hare Krsna devotee. I also have a reformed Jewish background, like Mrs. Eisenberg. I mention this because my experiences have been in great contrast to the ones you’ve heard expressed this morning by Mrs. Eisenberg. My son is a devotee, although he lives outside the temple right now. He dresses as any student at the University of Chicago dresses. He’s getting a Ph.D. He has a family. But he is a Hare Krsna devotee. When he goes to the temple he puts on the robes because he wishes to. He doesn’t shave his head, because he doesn’t choose to right now. It’s not required for devotees to do that. It doesn’t mean that he’s covering up anything. On the contrary, he’s very outspoken about who he is. He’s very proud of it.

Moderator: And you’ve accepted it.

Mrs. Hoffman: I’ve more than accepted it—I’ve found that it’s been an enrichment to me to learn more about what he’s into. First of all, I feel that it’s—

Moderator: Do you see him often?

Mrs. Hoffman: Yes. Very often.

Moderator: Can you see him any time you want to?

Mrs. Hoffman: He stays at my house with his whole family for days at a time.

Moderator: Do his eyes look glazed?

Mrs. Hoffman: Oh, on the contrary! He is a bright, with-it human being, and I’m very, very proud of him.

Moderator: I’m sure Steve Eisenberg is a bright kid, too.

Mrs. Hoffman: Of course. He’s a bright human being, I’m sure, who really should not have been a Hare Krsna devotee, obviously.

Moderator: I think one of the biggest problems is that we in this country, if we allow freedom of religion to exist—and we do … It is not the Krsnas that we object to. We basically say in this country, “Try it. You might like it.” The problem comes, I think—and Mrs. Eisenberg and her son feel—that if you don’t like it you can’t get out. Is that right?

Mrs. Eisenberg: That’s absolutely correct.

Mrs. Hoffman: Oh, that is absolutely incorrect. Anybody who wishes to can leave at any time. I have never had the feeling my son is staying because he must stay. Never. Absolutely never.

Mrs. Eisenberg: I feel very sorry for you. You don’t have your son with his own power of thinking.

Mrs. Hoffman: Oh, my son has every bit of his own power of thinking. He’s just gotten degrees from Harvard and the University of Chicago, and believe me if you can’t think in these institutions you certainly can’t survive there. [Applause.]

Mrs. Eisenberg: And when he graduates he will turn all of his earnings—his beautiful earning power—over to Krsna, and they will become the benefactors.

Mrs. Hoffman: He’s earning right now, and he is not turning all of his earnings over to Krsna.

Mrs. Eisenberg: Oh, they don’t permit that. They must have your earnings.

Mrs. Hoffman: That’s not true. Positively not true. He’s been earning money intermittently while he’s been going to school. He’s in India now on a research grant, and he is not turning the money over to Krsna. He’s living on it.

Mrs. Eisenberg: And he goes around and does research for them. When Krsna sent my son to India, he bathed in the Ganges with corpses and dreadful things. [Titters from the audience.]

Mrs. Hoffman: Excuse me. The Hare Krsna movement did not send my son to India. He’s there on a private research project—

Mrs. Eisenberg: Oh, I see. Which you’re paying for.

Mrs. Hoffman: No. I’m not paying for it.

Moderator: What happens to your son’s—

Mrs. Hoffman: I’d like to point out that the program this morning could be valuable if we realize where our positions are coming from. Exactly what is it that we want to accomplish? Do we want to obliterate the Hare Krsnas from the face of the earth?

Mrs. Eisenberg: Yes!

Mrs. Hoffman: Would you feel better?

Mrs. Eisenberg: Yes! [Her sympathizers in the audience applaud vigorously.] Absolutely. You would too if you had your son thinking on his own.

Mrs. Hoffman: I don’t want you to tell me, Mrs. Eisenberg, what I would think, because that’s absolutely not true.

Moderator [taking each mother by the arm]: See, I think this is valuable. I mean, I think the two of you talking about this is very valuable because a lot of positive and a lot of negative feelings come out. You represent the feelings of a lot of people—both of you. So I think this is valuable.

Mrs. Eisenberg: No, I think she’s the exception, because most of the parents will not subject their child to being in slavery. They raise their child to be a free-thinking person.

Mrs. Hoffman: Excuse me, but I’d just like to say that I feel that’s an insult to me—that you’re saying that I am enjoying my son’s being a slave. Mrs. Eisenberg; You probably do.

Mrs. Hoffman: If you ever knew my son, he is far from ever being the sort of person who would ever be a slave. He is very, very outspoken, very determined, very bright, very with it. And one of the things that I feel upset about is: I don’t feel that we have to agree with everything that goes on in the Hare Krsna movement. I don’t agree with everything. But the reason why I got up at five this morning to come here from Washington, D.C., is because I am terrified of what’s happening to our country, which is supposed to be a country that is …

Moderator: Tolerant?

Mrs. Hoffman: Yes. Permitting religious freedom. And not only that, but we have a lot to gain in terms of enrichment from differences. But what’s happening is that as soon as anyone is different, we’re frightened. We rush off to toss their minds around like a tennis ball. I mean, the thought of parents hiring, at the expense of, I’ve heard, fifteen thousand dollars some of these deprogrammers get—which is a great business—

Mrs. Eisenberg: It’s worth every penny.

Moderator [to Mrs. Eisenberg]: What?

Mrs. Eisenberg: Worth every penny. [Applause.] I worked for two years to pay off the debt, and enjoyed every penny that I had to pay for this.

Mrs. Hoffman: Mrs. Eisenberg, I don’t mean to be disrespectful, but I don’t think you have any respect for your child if you feel that his mind can just be tossed back and forth this way. I don’t feel that my son’s mind could be. In fact, I know it couldn’t.

[At this point the show broke for a commercial, bringing the dialogue to an end.]

Thinking it Over

by Nannette Hoffman

After interviews or debates, one invariably focuses on all that was not included. I wish I had responded more strongly, for example, to Mrs. Eisenberg’s enthusiasm for the idea of ridding the earth of all Hare Krsna devotees. I find it difficult to understand how a person of Jewish background, especially, could favor such an outrageous position.

Of course, as a parent I too have fear of the unknown. When my son first told me he wanted to join a strange religious group that I knew nothing about, I felt torn apart. Why had my tradition, the Jewish tradition, not been sufficient for him?

Back in 1973 the words Hare Krsna had no meaning for me. Somehow my education had seemed to omit mention in any s detail of India or Hinduism, all the way a through to an M.A. in literature.

But the saving aspect of the situation was that I sincerely respect my son. I saw his determination, and, believing in his fine qualities as a human being, I assumed that anything that captured his interest so fully must have value. It followed that I had to do something about my own ignorance.

Instead of telling my son “I’m right, and you must listen to me,” I decided to educate myself about the religious tradition of India. A lot of questions had to be answered. My son and I had many long talks, often lasting way into the night. He was eager to explain anything I wished to understand about the religion and the philosophy that excited him so much. I never hesitated to object or to question any ideas or to express my true feelings. These discussions brought us even closer.

Next I visited the Hare Krsna temple in Washington, D.C., then on Q St. NW. The chanting and singing initially made me feel strange and out of place. But the food served at the Sunday feast was always a treat. The devotees explained that all the food had been offered to God; therefore it would be of special benefit to all who ate it. Each Sunday it is prepared by devotees and given to all free of charge. I was impressed, not only by the sharing of food but by the beautiful thought behind it.

Since those early days I have come a long way. In the fall of 1980 I lived for eight weeks among the devotees at the temple in Bombay. The religious life they lead became part of my own experience. When they felt joy, I too became part of it. When there were problems, I listened and joined their sadness. My respect for them grew as I watched many who could be leading more comfortable lives in America work long hours for a cause in which they believe—the striving to become more spiritual, more devoted to God.

Back in America, I am shocked that a lovely young woman, Kim Perrine, has recently been kidnapped and tormented by outlaws hired by her parents, all for the “crime” of being a devotee. Ms. Perrine tells of the horrors of her imprisonment for an entire month. No young person in a free society should ever be subjected to such an ordeal!

As an American, I hope that during my lifetime the Krsna religion is permitted to take its place among other major religions here, that it is given the respect to which it is legally entitled, and which it unquestionably deserves.

“Deprogramming”: A Personal Experience

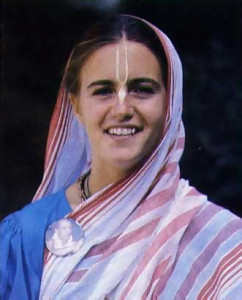

by Krsna-devi dasi

This is a condensed form of a statement made by Kim Perrine at a press conference on August 3. The conference took place at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

My name is Krsna-devi dasi. (My legal name is Kim Perrine.) I am 22 years old. I became a member of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness a year ago, and for a year prior to joining I studied the philosophy and practices of the Society. I found it to be based on the core of Hindu philosophy and culture, bhakti-yoga—the science of linking up with God through devotional service.

On June 23, 1982, I was in Baltimore, walking south on Charles Street near 30th Street, when a van pulled up to the curb in front of me. Two large, rough-looking men burst out of the doors and ran toward me. I turned to run north, but the car behind them pulled up on the curb, almost hitting me. I screamed. They grabbed me and pulled me back to the van, scraping my ankles and bruising my ribs. They threw me in the van, lay on top of me, and gagged me. From the back of the van my mother and stepfather came forward and said, “It’s all right, Kim, you’ve been brainwashed by the Hare Krsnas, and these men are going to help you return to normal life.”

After we crossed state lines the two thugs sat me up and then sat down on either side of me, practically on top of me. We drove straight to Ohio—about a ten-hour drive. They wouldn’t even stop to let me go to the bathroom. They made me use a bucket in the van.

In Ohio I was locked in a room so small that the bed practically filled it, and all the windows were boarded up. The room was in a small run-down cabin in an old camp near Lake Milton. The front door was locked, and a security guard sat next to it at all times. They kept me in that cabin more than two weeks—in 90-degree weather with no ventilation.

During that time I couldn’t wear my religious clothes or pray (they took everything from me the first night and burned it: clothes, neck beads, prayer beads, etc.). They made me change all my personal habits—how I ate, how I went to the bathroom, how I spoke, even how I sat and walked—in an effort to destroy the person I’d been before they’d kidnapped me. They constantly blasphemed my religious doctrines twelve to fourteen hours a day, reducing me to tears and depression. They even threatened to commit me to a mental institution. They deprived me of sleep and repeatedly threatened to keep me locked up. They verbally abused me, calling me things such as “slave,” “selfish arrogant bitch,” and “whore.” They even tried sexual aggression to dehumanize me and destroy my religious beliefs and lifestyle.

I was forced to eat nonvegetarian foods, gamble, and drink wine, all of which are against my religious principles. One of my captors tried several times to seduce me. That was “an important part of the rehabilitation,” he said.

They made me write letters, sign papers, and confess to things I had never done. When they forced me to read a book on brainwashing, I found that the methods I was reading about were the things they were doing to me!

The thugs said they wouldn’t release me until they were satisfied I had completely severed my involvement with Krsna consciousness. They said they would keep me locked up until I made a “free” decision to leave Krsna. Although I refused to give up struggling for my rights and beliefs, I decided the only way out would be to play along with them until I could get away.

After about seventeen days they began to trust me (actually, another case came in and they needed the “deprogramming cabin” for her). So they moved me to another cabin, with chains on the windows, where I was either closely guarded or locked in. All together I spent one month in captivity before I was able to escape.

I have never been treated in such a demeaning way in my entire life. Except for others who are victims of these same criminals, I know of no one who has been treated like this. Even animals receive better treatment.

Since I returned to Baltimore, law enforcement officials have been incredibly slow to respond to my complaints. Indeed, they’ve advised me just to forget about the whole episode. A city police officer and even an FBI agent said if they had a child like me they would also kidnap and deprogram him. But they have no idea what a horrible experience it was, and still is. I still wake up crying from nightmares brought on by that hellish month. I’m filled with fear that what happened then may happen again. It will take a long time before the mental scars are healed.

My parents were exploited and misinformed by these men, who induced them to pay more than $15,000 for my kidnapping and abortive “deprogramming.” I have asked my parents for their cooperation in bringing these criminals to justice, but they have refused. I don’t want to prosecute my parents, but I have to in order to get to the deprogrammers.

I appeal to the parents of Hare Krsna devotees all over the world: Don’t ruin a cherished relationship with your son or daughter by putting them through an experience like mine. And I also appeal to law agencies to act decisively to bring these criminals to justice.

Leave a Reply