The Chapati: Bread Fit for the Lord

Simple, wholesome, delicious: The qualities that made this

traditional unleavened bread the choice for offering to Krsna

five centuries ago make it a staple in Krsna’s cuisine today.

by Visakha-devi dasi

Madhavendra Puri awoke and lamented, “I saw the Lord directly, but I could not even recognize Him!”

The previous day, while Madhavendra Puri had been fasting and meditating beneath a tree in the holy land of Vrndavana a beautiful cowherd boy had appeared before him and, smiling enchantingly, offered him a pot of milk. Madhavendra Puri had accepted the milk, but although the boy had promised to return for the empty pot, He never had. The whole night Madhavendra Puri had chanted Hare Krsna, waiting for that beautiful boy to return, until towards morning he had dozed a little and dreamt that the boy was clasping his hand and taking him to a bush in the jungle.

“I reside in this bush,” the boy said, “and because of this I suffer very much from rain. winds, severe cold, and scorching heat. Please bring the people of the village and get them to take Me out of this bush. Then have them situate Me nicely on the hilltop.

“My name is Gopala,” the boy said. (Gopala is a name for Krsna that means “cowherd boy.”) “When soldiers attacked Vrndavana, the priest who was serving Me hid Me here. Then he ran away in fear. Since then I have been staying in this bush. It is very good that you’ve come here. Now just remove Me with care.” With this, the boy disappeared.

Upon awakening, Madhavendra Puri felt sorry because he had not recognized the boy in his dream as Gopala, the Supreme Personality of Godhead. But Madhavendra Puri had full faith in the words Gopala had spoken in the dream. So he entered the village and explained the situation to the people. Together they went to the exact spot in the jungle that Gopala had indicated, excavated the carved stone Deity form of the Lord, and carried Him to the hilltop.

Madhavendra Puri never thought that the Gopala Deity was simply a stone statue representing the Lord. He saw the Deity as directly the Supreme Personality of Godhead Himself in all His fullness and opulence. Madhavendra Puri knew that although God is present everywhere, He personally comes as the Deity to accept and reciprocate His devotees’ loving service. To those with materialistic vision the form of the Deity may appear like inert matter, but a pure devotee realizes that there is no difference between the Deity of the Lord and the Lord Himself. Such a devotee serves the Deity just as he would serve the Lord directly. So the Deity of Lord Gopala, by His own transcendental desire, engaged Madhavendra Puri and hundreds of local people in His service, thus increasing their love for Him. After all, if the Lord wants to come among us as a Deity like Gopala, who in this world can stop Him?

The villagers welcomed Gopala with the melodious sounds of bugles, drums, chanting, and singing, while Madhavendra Puri washed the Lord’s transcendental body with hundreds of pots of water, and with pots of yogurt, milk, honey, sugar, and ghee (purified butter). He massaged the Lord with fine oils, bathed Him again, and dressed Him in new garments.

Then the villagers offered Lord Gopala prayers, obeisances, and their entire stocks of rice, wheat flour, and dal (see BTG Vol. 17, No. 4.) They brought so much food that it covered the entire surface of the hill. Expert cooks prepared dozens of varieties of vegetables, soups, cakes, rices, and chapatis (the subject of this month’s recipe). They placed the rice on leaves and surrounded it with stacks of chapatis, each amply covered with ghee. Then they placed all the vegetable dishes in pots and put them around the chapatis. Finally, they placed pots of yogurt, milk, buttermilk, yogurt-cheese, sweet rice, cream, and solid cream alongside the vegetables. Thus they celebrated the lavish festival called annakuta, and Madhavendra Puri personally offered everything to the Deity of Gopala with great devotion.

Having been hungry for many days, Gopala happily ate all the food and told Madhavendra Puri, “I have accepted your service because of your intense love for Me.” Although Gopala ate all the food, leaving not a morsel. He again restored it all by His transcendental potency. Such are the pastimes of the Deity of the Lord.

After the Lord was satisfied, Madhavendra Puri gathered all the cooks and said, “Now feed everyone sumptuously, from the children up to the aged!” Local and neighboring villagers feasted side by side on the lavish spread of prasadam (food offered to Krsna). Everyone was astonished to see the influence of Madhavendra Puri.

As the entire region gradually heard of the appearance of Gopala, people from more distant villages began coming to visit Him. Each group of villagers wanted to perform the annakuta ceremony, so day after day they brought rice, dal, flour, vegetables, ghee, milk, sweets, flowers, and various other offerings for the Deity. The cooks again and again prepared and offered dishes to Gopala and distributed prasadam to all. Lord Gopala was very pleased, as was His devotee Madhavendra Puri.

* * *

Madhavendra Puri offered chapatis to Lord Gopala in the fifteenth century, when this pastime took place. Similarly, 4500 years before, when Lord Krsna resided in Vrndavana, He also enjoyed chapatis. If you’re inclined to, you can make chapatis in your own kitchen, offer them to Krsna, and partake of this simple yet delicious and nourishing bread.

There is a specific, formal process for offering food to Krsna that devotees follow in Krsna’s temples. For your offering at home, however, you can begin with a few simple procedures. First, while preparing the dish, try to remember that it is for Krsna’s pleasure. Second, never taste the preparation before offering it: Krsna should enjoy it first. Third, when the preparation is done, place a portion before a picture of Krsna; then chant Hare Krsna and pray for the Lord to accept the offering.

(Recipe by Yamuna-devi dasi)

Basic Unleavened Whole-wheat Bread (chapati)

The most popular of all unleavened breads, chapatis are traditionally made with stone-ground whole-wheat flour. Thus they’re rich in fiber, vitamins B and E, protein, iron, unsaturated fats, and carbohydrates. Like all whole-wheat breads, chapatis also contain phytic acid, a chemical that regulates the amount of calcium and other minerals the body absorbs. So while connoisseurs can relish chapatis for their refined taste, texture, and aroma, natural food fans can enjoy them for their varied nutritional content as well.

The most popular of all unleavened breads, chapatis are traditionally made with stone-ground whole-wheat flour. Thus they’re rich in fiber, vitamins B and E, protein, iron, unsaturated fats, and carbohydrates. Like all whole-wheat breads, chapatis also contain phytic acid, a chemical that regulates the amount of calcium and other minerals the body absorbs. So while connoisseurs can relish chapatis for their refined taste, texture, and aroma, natural food fans can enjoy them for their varied nutritional content as well.

Note concerning flour:

Most Vedic breads are made with a kind of stone-ground whole-wheat flour called atta, or chapati flour. This flour, available in Indian grocery stores, is quite different from the kinds available in supermarkets and health-food stores. chapati flour consists of whole grains of wheat finely milled to a near powder. (Cooks in India usually make it even finer by sieving it through a very fine screen in a utensil called a chalni.) chapati flour is tan or buff in color and bursting with nutrition. Doughs made with it are velvety smooth, knead readily, and respond easily to shaping.

If chapati flour is unavailable, you can use regular whole-wheat flour. You should either sieve this flour to reduce its coarse texture or replace a portion of it with unbleached or regular all-purpose flour. How much all-purpose flour you should add depends on the quality of your whole-wheat flour, but generally two parts whole wheat to one part all-purpose gives good results. (For best results, use freshly milled flours.)

To measure the flour, first sieve it and then lightly spoon it into a measuring cup until it overflows the rim. Finally, level it off gently with a knife. If you pack the flour into the measuring cup or shake the cup, you’ll get an inaccurate measurement because of compression or settling of the flour.

In following this recipe, begin with the least amount of water suggested. If the dough turns out too soft, add additional flour. Remember:

Flours vary according to the type of wheat they’re milled from, the processing they undergo, and the amount of moisture they absorb during storage. So even the most accurate measurements may need small adjustments.

Preparation time: 1 to 2 minutes per chapati

Yield: 10 to 12 chapatis

Ingredients:

2 ½ to 2 2/3 cups sieved chapati or whole-wheat flour

½ teaspoon salt (optional)

2/3 to 1 cup lukewarm water

4 to 5 teaspoons melted butter or ghee (see BACK TO GODHEAD, Vol. 17, No. 2-3)

Equipment:

A flat surface near the stove

A flat iron griddle Two burners

A cake rack (needed only if you’re using electric heat)

A pair of tongs

A rolling pin

A cake tin or pie tin lined with a thick clean kitchen towel (needed only if you’re not serving the chapatis right off the stove)

A pastry brush or teaspoon

To prepare the dough:

First put aside ½ cup of flour for rolling the chapatis. Then add the salt to the remaining flour. Now fill a receptacle with about 1 cup of lukewarm water. Holding the receptacle in one hand, add about 2/3 cup of water to the flour and work it with your other hand until it begins to hold together. Mix vigorously, adding enough water to make a pliable, soft dough. (The look and feel of the dough will determine how much water you need.) Fold and knead the dough by pressing it with your knuckles or palms until it is silky smooth, or for about ten minutes. Now gather the dough into a compact, smooth ball, place it in a bow], rub it with water until a thin film forms, and drape it with a damp towel. Allow the dough to sit for at least ½ hour at room temperature. If the dough is covered well, you may let it sit as long as 6 to 8 hours while the water and gluten in the wheat form an elastic, weblike framework.

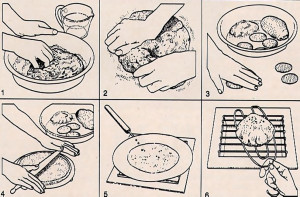

To shape and cook the chapatis:

Prepare the cooking area by collecting the necessary ingredients and equipment. (If you don’t plan to serve the chapatis one after another right off the stove, place each cooked chapati between the folds of the towel in the cake tin or pie tin. But remember the chapatis must have breathing space, so don’t cover them so tightly that they become soggy from the steam inside them.) Place a bowl with the melted butter or ghee nearby, along with the pastry brush or teaspoon. Preheat the flat iron griddle over medium heat for about three minutes. Take the ½ cup of wholewheat flour you saved and place it in a small, shallow dish.

Knead the dough, adding more flour if it’s too sticky. Divide the dough into about a dozen equal pieces. Then take the pieces one at a time, coat them with a little flour, and roll them between your palms to shape round, smooth balls. Place the balls on a plate and drape them with a damp towel.

Now take the first ball and immerse it in enough flour to prevent sticking. Then flatten the ball into a two-inch patty, dip the patty into the flour on both sides, and, using a rolling pin, roll it out from the center to make a disk about 3 ½ inches across. Dip the disk into the flour on both sides and then roll it in all directions until the dough is evenly thick all around. The circle of dough should be as thin and as round as possible, and it should measure about 5 to 6 inches across. While rolling the chapati, use just enough flour to prevent it from sticking.

Lift up the flat disk of dough, slap it back and forth from one palm to the other to shake off any excess flour, and then slip it onto the preheated griddle. Cook for about 40 to 50 seconds, or until you see small white blisters appear on the surface of the dough. Now turn the chapati over and cook for another 35 to 45 seconds, or until small brown spots form on the underside and the surface blisters with air pockets.

Lift the chapati off the griddle and carefully place it directly on a high gas flame or a cake rack placed over an electric burner set on “high.” Within ten seconds the chapati will swell, fill with hot steam, and puff up. Use the pair of tongs to turn the chapati over, and then toast it until the puffed surface is marked with tiny black spots.

Remove the chapati from the heat and slap out the hot air so the chapati collapses. Brush one side with melted butter or ghee and offer to Krsna immediately or place between the folds of a thick clean kitchen towel for offering later.

Note:

Try to establish a rhythm in your movements so you’re rolling one chapati while another is baking. This way you can make a chapati every two minutes or so.

Leave a Reply