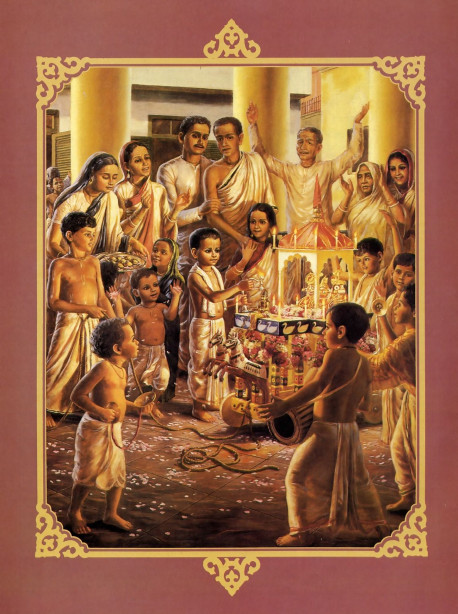

A Childhood Chariot Festival

1902: Calcutta

Inspired by the huge chariot festival at Puri,

the young Srila Prabhupada enlivened his family and friends

to stage a miniature Ratha-yatra in his neighborhood.

by Srila Satsvarupa dasa Goswami

Excerpted from Srila Prabhupada-lilamrta, by Satsvarupa dasa Goswami. © 1981 by the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust.

Srila Prabhupada’s childhood was a rich mixture of devotion, education, and adventure. His father, Gour Mohan De, tried to fulfill his every wish, and when the five-year-old child wanted to put on a miniature Ratha-yatra chariot festival, Gour Mohan gladly helped him. Later the boy would live through local Hindu-Muslim riots and his own mother’s premature death, all the while sustained by his father’s strong character and his faith in Krsna.

Abhay was enamored with the Ratha-yatra festivals of Lord Jagannatha, held yearly in Calcutta. The biggest Calcutta Ratha-yatra was the Mulliks’, with three separate carts bearing the deities of Jagannatha, Baladeva, and Subhadra (Lord Krsna. His brother, and His sister). Starting from the Radha-Govinda temple, the carts would proceed down Harrison Road for a short distance and then return. The Mulliks would distribute large quantities of Lord Jagannatha’s prasadam (sanctified food) to the public on this day.

Ratha-yatra was held in cities all over India, but the original, gigantic Ratha-yatra, attended each year by millions of pilgrims, took place three hundred miles south of Calcutta at Jagannatha Puri. For centuries at Puri, three wooden carts forty-five feet high had been towed by the crowds along the two-mile parade route, in commemoration of one of Lord Krsna’s eternal pastimes. Abhay had heard how Lord Caitanya Himself, four hundred years before, had danced and led ecstatic chanting of Hare Krsna at the Puri Ratha-yatra festival. Abhay would sometimes look at the railway timetable or ask about how he could collect the money and go there.

Abhay wanted to have his own cart and to perform his own Ratha-yatra, and naturally he turned to his father for help. Gour Mohan agreed, but there were difficulties. When he took his son to several carpenter shops, he found that he could not afford to have a cart made. On their way home, Abhay began crying, and an old Bengali woman approached and asked him what the matter was. Gour Mohan explained that the boy wanted a Ratha-yatra cart but they couldn’t afford to have one made. “Oh, I have a cart,” the woman said, and she invited Gour Mohan and Abhay to her place and showed them the cart.

It looked old, but it was still operable, and it was just the right size, about three feet high. Gour Mohan purchased it and helped to restore and decorate it. Father and son together constructed sixteen supporting columns and placed a canopy on top, resembling as closely as possible the ones on the big carts at Puri. They also attached the traditional wooden horses and driver to the front of the cart. Abhay insisted that it must look authentic. Gour Mohan bought paints, and Abhay personally painted the cart, copying the Puri originals. His enthusiasm was great, and he became an insistent organizer of various aspects of the festival. But when he tried making fireworks for the occasion from a book that gave illustrated descriptions of the process, his mother, Rajani, intervened.

Abhay engaged his playmates in helping him, especially his sister Bhavatarini, and he became their natural leader. Responding to his entreaties, amused mothers in the neighborhood agreed to cook special preparations so that he could distribute the prasadam at his Ratha-yatra festival.

Like the festival at Puri, Abhay’s Ratha-yatra ran for eight consecutive days. His family members gathered, and the neighborhood children joined in a procession, pulling the cart, playing drums and hand cymbals, and chanting. Wearing a dhoti and no shirt in the heat of summer, Abhay led the children in chanting Hare Krsna and in singing the appropriate Bengali bhajana, Ki kara rai kamalini.

What are you doing, Srimati Radharani?

Please come out and see.

They are stealing Your dearmost treasure—

Krsna, the black gem.

If the young girl only knew!

The young boy Krsna,

Treasure of Her heart,

Is now forsaking Her.

Abhay copied whatever he had seen at adult religious functions, including dressing the deities, offering the deities food, offering arati with a ghee lamp and incense, and making prostrated obeisances. From Harrison Road the procession entered the circular road inside the courtyard of the Radha-Govinda temple and stood awhile before the Deities. Seeing the fun, Gour Mohan’s friends approached him: “Why haven’t you invited us? You are holding a big ceremony and you don’t invite us? What is this?”

“They are just children playing,” his father replied.

“Oh, children playing?” the men joked. “You are depriving us by saying this is only for children?”

While Abhay was ecstatically absorbed in the Ratha-yatra processions, Gour Mohan spent money for eight consecutive days, and Rajani cooked various dishes to offer, along with flowers, to Lord Jagannatha. Although everything Abhay did was imitation, his inspiration and steady drive for holding the festival were genuine. His spontaneous spirit sustained the eight-day children’s festival, and each successive year brought a new festival, which Abhay would observe in the same way.

* * *

When Abhay was about six years old, he asked his father for a Deity of his own to worship. Since infancy he had watched his father doing puja (formal worship) at home and had been regularly seeing the worship of Radha-Govinda and thinking, “When will I be able to worship Krsna like this?” On Abhay’s request, his father purchased a pair of little Radha-Krsna Deities and gave Them to him. From then on, whatever Abhay ate he would first offer to Radha and Krsna, and imitating his father and the priests of Radha-Govinda, he would offer his Deities a ghee lamp and put Them to rest at night.

Abhay and his sister Bhavatarini became dedicated worshipers of the little Radha-Krsna Deities, spending much of their time dressing and worshiping Them and sometimes singing bhajanas. Their brothers and sisters laughed, teasing Abhay and Bhavatarini by saying that because they were more interested in the Deity than in their education they would not live long. But Abhay replied that they didn’t care.

In addition to the education Abhay received at the kindergarten, he also received private tutoring at home from his fifth year to his eighth. He learned to read Bengali and began learning Sanskrit. Then in 1904, when he was eight years old, Abhay entered the nearby Mutty Lall Seal Free School, on the corner of Harrison and Central roads.

Mutty Lall was a boys’ school established in 1842 by a wealthy suvarna-vanik Vaisnava (devotee of Krsna). The building was stone, two stories, and surrounded by a stone wall. The teachers were Indian, and the students were Bengalis from local suvarna-vanik families. Dressed in their dhotis and kurtas, the boys would leave their mothers and fathers in the morning and walk together in little groups, each boy carrying a few books and his tiffin, the Indian equivalent of a lunchbox. Inside the school compound, they would talk together and play until the clanging bell called them to their classes. The boys would enter the building, skipping through the halls, running up and down the stairs, coming out to the wide front veranda on the second floor, until the teachers gathered them all before their wooden desks and benches for lessons in math, science, history, geography, and their own Vaisnava religion and culture.

Classes were disciplined and formal. Each long bench held four boys, who shared a common desk, with four inkwells. If a boy were naughty his teacher would order him to “stand up on the bench.” A Bengali reader the boys studied was the well-known Folk Tales of Bengal, a collection of traditional Bengali folk tales, stories a grandmother would tell local children—tales of witches, ghosts, Tantric spirits, talking animals, saintly brahmanas (or sometimes wicked ones), heroic warriors, thieves, princes, princesses, spiritual renunciation, and virtuous marriage.

In their daily walks to and from school, Abhay and his friends came to recognize, at least from their childish viewpoint, all the people who regularly appeared in the Calcutta streets: their British superiors traveling about, usually in horse-drawn carriages; the hackney drivers; the bhangis, who cleaned the streets with straw brooms; and even the local pickpockets and prostitutes who stood on the street corners.

Abhay turned ten the same year the rails were laid for the electric tram on Harrison Road. He watched the workers lay the tracks, and when he first saw the trolley car’s rod touching the overhead wire, it amazed him. He daydreamed of getting a stick, touching the wire himself, and running along by electricity. Although electric power was new in Calcutta and not widespread (only the wealthy could afford it in their homes), along with the electric tram came new electric streetlights—carbon-arc lamps—replacing the old gaslights. Abhay and his friends used to go down the street looking on the ground for the old, used carbon tips, which the maintenance man would leave behind. When Abhay saw his first gramophone box, he thought an electric man or a ghost was inside the box singing.

Abhay liked to ride his bicycle down the busy Calcutta streets. Although when the soccer club had been formed at school he had requested the position of a goalie so that he wouldn’t have to run, he was an avid cyclist. A favorite ride was to go south towards Dalhousie Square, with its large fountains spraying water into the air. That was near Raj Bhavan, the viceroy’s mansion, which Abhay could glimpse through the gates. Riding further south, he would pass through the open arches of the Maidan, Calcutta’s main public park, with its beautiful green flat land spanning out towards Chowranghee and the stately buildings and trees of the British quarter. The park also had exciting places to cycle past: the racetrack, Fort William, the stadium. The Maidan bordered the Ganges (known locally as the Hooghly), and sometimes Abhay would cycle home along its shores. Here he saw numerous bathing ghatas, with stone steps leading down into the Ganges and often with temples at the top of the steps. There was the burning-ghata, where bodies were cremated, and, close to his home, a pontoon bridge that crossed the river into the city of Howrah.

* * *

At age twelve, though it made no deep impression on him, Abhay was initiated by a professional guru. The guru told him about his own master, a great yogi, who had once asked him, “What do you want to eat?”

Abhay’s family guru had replied, “Fresh pomegranates from Afghanistan.”

“All right,” the yogi had replied. “Go into the next room.” And there he had found a branch of pomegranates, ripe as if freshly taken from the tree. A yogi who came to see Abhay’s father said that he had once sat down with his own master and touched him and had then been transported within moments to the city of Dvaraka by yogic power.

Gour Mohan did not have a high opinion of Bengal’s growing number of so-called sadhus—the nondevotional impersonalist philosophers, the demigod worshipers, the ganja smokers, the beggars—but he was so charitable that he would invite the charlatans into his home. Every day Abhay saw many so-called sadhus, as well as some who were genuine, coming to eat in his home as guests of his father, and from their words and activities Abhay became aware of many things, including the existence of yogic powers. At a circus he and his father once saw a yogi tied up hand and foot and put into a bag. The bag was sealed and put into a box, which was then locked and sealed, but still the man came out. Abhay, however, did not give these things much importance compared with the devotional activities his father had taught him, his worship of Radha-Krsna, and his observance of Ratha-yatra.

* * *

Hindus and Muslims lived peacefully together in Calcutta, and it was not unusual for them to attend one another’s social and religious functions. They had their differences, but there had always been harmony. So when trouble started, Abhay’s family understood it to be due to political agitation by the British. Abhay was about thirteen years old when the first Hindu-Muslim riot broke out. He did not understand exactly what it was, but somehow he found himself in the middle of it.

Srila Prabhupada: All around our neighborhood were Muhammadans. The Mullik house and our house were surrounded by what is called kasba and basti. So the riot was there, and I had gone to play. I did not know that the riot had taken place in Market Square. I was coming home, and one of my friends said, “Don’t go to your house. That side is rioting now.”

We lived in the Muhammadan quarter, and the fighting between the two parties was going on. But I thought maybe it was something like two gundas [hoodlums] fighting. I had seen one gunda once stabbing another gunda, and I had seen pickpockets. They were our neighbormen. So I thought it was like that: this is going on.

But when I came to the crossing of Harrison Road and Holliday Street I saw one shop being plundered. I was only a child, a boy. I thought, “What is this happening?” In the meantime, my family, my father and mother, were at home frightened, thinking, “The child has not come.” They became so disturbed they came out of the home expecting, “Wherefrom will the child come?”

So what could I do? When I saw the rioting I began to run towards our house, and one Muhammadan, he wanted to kill me. He took his knife and actually ran after me. But I passed somehow or other. I was saved. So as I came running before our gate, my parents got back their life.

So without speaking anything I went to the bedroom, and it was in the winter. So without saying anything, I laid down, wrapped myself with a quilt. Then later I was rising from bed, questioning, “Is it ended? The riot has ended? “

When Abhay was fifteen he was afflicted with beriberi, and his mother, who was also stricken, regularly had to rub a powder of calcium chloride on his legs to reduce the swelling. Abhay soon recovered, and his mother, who had never stopped any of her duties, also recovered.

But only a year later, at the age of forty-six, his mother suddenly died. Her passing away was an abrupt lowering of the curtain, ending the scenes of his tender childhood: his mother’s affectionate care, her prayers and mantras for his protection, her feeding and grooming him, her dutifully scolding him. Her passing affected his sisters even more than him, though it certainly turned him more towards the affectionate care of his father. He was already sixteen, but now he was forced to grow up and prepare to enter on his own into worldly responsibilities.

His father gave him solace. He instructed Abhay that there was nothing for which to lament: the soul is eternal, and everything happens by the will of Krsna, so he should have faith and depend upon Krsna. Abhay listened and understood.

The biography of Srila Prabhupada continues next month with an account of his first meeting with his spiritual master, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura.

The Ratha-yatra festival is a mass movement for enlightening people about the Krishna consciousness movement. To take part in these festivals is a step forward towards self-realization. To support this, Srila Prabhupada quotes a verse, “