A Refuge For The Hippies

Winter-spring, 1967: San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district. “It was like opening a temple in a battlefield.”

by Srila Satsvarupa dasa Goswami

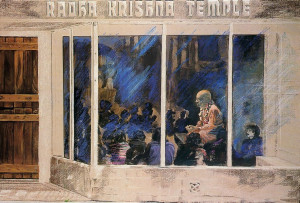

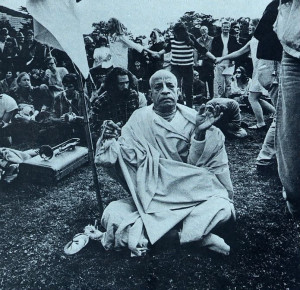

Srila Prabhupada had come to San Francisco from New York just when the hippie movement was reaching its height. Now he found that his small temple on Frederick Street, in the heart of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, was becoming a spiritual haven for troubled, searching, and sometimes desperate young people.

Srila Prabhupada had come to San Francisco from New York just when the hippie movement was reaching its height. Now he found that his small temple on Frederick Street, in the heart of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, was becoming a spiritual haven for troubled, searching, and sometimes desperate young people.

Prabhupada’s thoughtful followers felt that some of the candidates for initiation in San Francisco did not intend to fulfill the exclusive lifelong commitment a disciple owes to his guru. “Swamiji,” they would say, “some of these people come only for their initiation. We have never seen them before, and we never see them again.” Srila Prabhupada replied that that was the risk he had to take. One day in a lecture in the temple, he explained that although the reactions for a disciple’s past sins are removed at initiation, the spiritual master remains responsible until the disciple is delivered from the material world. Therefore, he said, Lord Caitanya warned that a guru should not accept many disciples.

One night in the temple during the question-and-answer session, a big, bearded fellow raised his hand and asked Prabhupada, “Can I become initiated?”

The brash public request annoyed some of Prabhupada’s followers, but Prabhupada was serene. “Yes,” he replied. “But first you must answer two questions. Who is Krsna?”

The boy thought for a moment and said, “Krsna is God.”

“Yes,” Prabhupada replied. “And who are you?”

Again the boy thought for a few moments and then replied, “I am the servant of God.”

“Very good,” Prabhupada said. “Yes, you can be initiated tomorrow.”

Srila Prabhupada knew that it would be difficult for his Western disciples to stick to Krsna consciousness and attain the goal of pure devotional service. All their lives they had had the worst of training, and despite their nominal Christianity and philosophical searching, most of them knew nothing of the science of God. They did not even know that illicit sex and meat-eating were wrong, although when he told them they accepted what he said. And they freely chanted Hare Krsna. So how could he refuse them?

Of course, whether they would be able to persevere in Krsna consciousness de-spite the ever-present attractions of maya would be seen in time. Some would fall—that was the human tendency. But some would not. At least those who sincerely followed his instructions to chant Hare Krsna and avoid sinful activities would be successful. Somehow or other, Srila Prabhupada would say, people should be engaged in Krsna consciousness. And this was the instruction of Lord Caitanya’s chief follower, Rupa Gosvami, who had written, tasmat kenapy upayena manah krsne nivesayet. . . : “Somehow or other, fix the mind on Krsna; the rules and regulations can come later.”

Of course, whether they would be able to persevere in Krsna consciousness de-spite the ever-present attractions of maya would be seen in time. Some would fall—that was the human tendency. But some would not. At least those who sincerely followed his instructions to chant Hare Krsna and avoid sinful activities would be successful. Somehow or other, Srila Prabhupada would say, people should be engaged in Krsna consciousness. And this was the instruction of Lord Caitanya’s chief follower, Rupa Gosvami, who had written, tasmat kenapy upayena manah krsne nivesayet. . . : “Somehow or other, fix the mind on Krsna; the rules and regulations can come later.”

Inherent in this attitude of Srila Prabhupada’s and Srila Rupa Gosvami’s was a strong conviction about the purifying force of the holy name; if engaged in chanting Hare Krsna, even the most fallen person could gradually become a saintly devotee. Srila Prabhupada would often quote a verse from Srimad-Bhagavatam affirming that persons addicted to sinful acts could be purified by taking shelter of the devotees of the Lord. He knew that every Haight-Ashbury hippie was eligible to receive the mercy of the holy name, and he saw it as his duty to his spiritual master to distribute the gift of Krsna consciousness freely, rejecting no one.

The morning and evening kirtana (chanting) had already made the Radha-Krsna temple popular in Haight-Ashbury, but when the devotees began serving a daily free lunch, the temple became an integral part of the community. Prabhupada told his disciples simply to cook and distribute prasadam—that would be their only activity during the day. In the morning they would cook, and at noon they would feed everyone who came—sometimes 150 or 200 hippies from the streets of Haight-Ashbury.

Before the morning kirtana, the girls would put oatmeal on the stove, and by breakfast there would be a roomful of hippies, most of whom had been up all night. The cereal and fruit was for some the first solid food in days.

But the main program was the lunch. Malati would go out and shop, getting donations whenever possible, for wholewheat flour, garbanzo flour, split peas, rice, and whatever vegetables were cheap or free: potatoes, carrots, turnips, rutabagas, beets. Then every day the cooks would prepare spiced mashed potatoes, buttered capatis, split-pea dal, and a vegetable dish—for two hundred people. The lunch program was possible because many merchants were willing to donate to the recognized cause of feeding hippies.

Harsarani: The lunch program attracted a lot of the Hippie Hill crowd, who obviously wanted food. They were really hungry. And there were other people who would come also, people who were working with the temple but weren’t initiated. The record player would be playing the Swamiji’s record. It was a nice family atmosphere.

Haridasa: The people would just all huddle together, and we would really line them wall to wall. A lot of them would simply eat and leave. But we were welcoming everybody. We were providing a kind of refuge from the tumult and madness of the street scene. So it was in that sense a hospital, and I think a lot of people were helped and maybe even saved. I don’t mean only their souls—I mean their minds and bodies were saved, because of what was going on in the streets that they just simply couldn ‘t handle. I’m talking about overdoses of drugs, people who were plain lost and needed comforting and who sort of wandered or staggered into the temple. Some of them stayed and became devotees, and some just took prasadam and left. Daily we had unusual incidents, and Swamiji witnessed it and took part in it. The lunch program was his idea.

Larry Shippen: Some of the community of loose people cynically took advantage of the free food. They didn’t appreciate the Swami, because they said he was, in his own way, an orthodox minister and they were much more interested in being unorthodox, it was a fairly cynical thing.

Those who were more interested and had questions—the spiritual seekers—would visit Swamiji in his room. Many of them would come in complete anxiety over the war in Vietnam or whatever was going on—trouble with the law, bad experiences on drugs, a falling out with school or family.

There was much public concern about the huge influx of youth into San Francisco, a situation that was creating an almost uncontrollable social problem. Police and welfare workers were worried about health problems and poor living conditions, especially in Haight-Ashbury. Some middle-class people feared a complete hippie take over. The local authorities welcomed the service offered by Swami Bhaktivedanta’s temple.

Master Subramuniya: The young people at that time were searching and needed somebody of a very high caliber who would take an interest in them and who would say, “You should do this, and you should not do that.” The consensus was that no one could tell the young people what to do, because they were completely out of hand with drugs and so forth. But Swamiji told them what to do, and they did it. And everyone was appreciative, especially the young people.

Harsarani: Just from a medical standpoint, doctors didn’t know what to do with people on LSD. The police and the free clinics in the area couldn’t handle the overload of people taking LSD. The police saw Swamiji as a certain refuge.

Michael Bowen: Bhaktivedanta had an amazing ability through devotion to get people off drugs, especially speed, heroin, burnt-out LSD cases—all of that.

Haridasa: The hippies needed all the help they could get, and they knew it. And the Radha-Krsna temple was certainly a kind of spiritual haven. Kids sensed it. They were running, living on the streets, no place where they could go, where they could rest, where people weren’t going to hurt them. A lot of kids would literally fall into the temple. I think it saved a lot of lives; there might have been a lot more casualties if it hadn’t been for Hare Krsna. It was like opening a temple in a battlefield. It was the hardest place to do it, but it was the place where it was most needed. Although the Swami had no precedents for dealing with any of this, he applied the chanting with miraculous results. The chanting was wonderful. It worked.

Srila Prabhupada knew that only Krsna consciousness could help. Others had their remedies, but Prabhupada considered them mere patchwork. He knew that ignorantly identifying the self with the body was the real cause of suffering. How could someone help himself, what to speak of others, if he didn’t know who he was, if he didn’t know that the body merelly covered the real self, the spirit soul, which could be happy only in his original nature as an eternal servant of Krsna?

Understanding that Lord Krsna considered anyone who approached Him a virtuous person and that even a little devotional service would never be lost and could save a person at the time of death, Srila Prabhupada had opened his door to everyone, even the most abject runaway. But for a lost soul to receive the balm of Krsna consciousness, he would first have to stay awhile and chant, inquire, listen and follow.

As Alien Ginsberg had advised five thousand hippies at the Avalon Ballroom, the early-morning kirtana at the temple provided a vital community service for those who were coming down from LSD and wanted “to stabilize their consciousness on reentry.”

On occasion, the “reentries” would come flying in out of control for crash landings in the middle of the night. One morning at two a.m. the boys sleeping in the storefront were awakened by a pounding at the door, screaming, and police lights. When they opened the door, a young hippie with wild red hair and beard plunged in, crying, “O Krsna, Krsna! Oh, help me! Oh, don’t let them get me. Oh, for God’s sake, help!”

A policeman stuck his head in the door and smiled. “We decided to bring him by here,” he said, “because we thought maybe you guys could help him.”

“I’m not comfortable in this body!” the boy screamed as the policeman shut the door. The boy began chanting furiously and turned white, sweating profusely in terror. Swamiji’s boys spent the rest of the early morning consoling him and chanting with him until the Swami came down for kirtana and class.

As for challengers, almost every night someone would come to argue with Prabhupada. One man came regularly with prepared arguments from a philosophy book, from which he would read aloud. Prabhupada would defeat him, and the man would go home, prepare another argument, and come back again with his book. One night, after the man had presented his challenge, Prabhupada simply looked at him without bothering to reply. Prabhupada’s neglect was another defeat for the man, who got up and left.

One morning a couple attended the lecture, a woman carrying a child and a man wearing a backpack. During the question-and-answer period the man asked,”What about my mind?” Prabhupada gave him philosophical replies, but the man kept repeating, “What about my mind? What about my mind?”

With a pleading, compassionate look, Prabhupada said, “I have no other medicine. Please chant this Hare Krsna. I have no other explanation. I have no other answer.”

But the man kept talking about his mind. Finally, one of the women devotees interrupted and said, “Just do what he says. Just try it.” And Prabhupada picked up his karatalas and began kirtana.

But the man kept talking about his mind. Finally, one of the women devotees interrupted and said, “Just do what he says. Just try it.” And Prabhupada picked up his karatalas and began kirtana.

One evening while Prabhupada was sitting on his dais, lecturing to a full house, a fat girl who had been sitting on the window seat suddenly stood up and began hollering at him. “Are you just going to sit there?” she yelled. “What are you going to do now? Come on! Aren’t you going to say something? What are you going to do now? Who are you?” Her action was so sudden and her speech so violent that no one in the temple responded. Unangered, Prabhupada sat very quietly. He appeared hurt. Only the devotees sitting closest to him heard him say softly, as if to himself, “It is the darkest of darkness.”

Another night while Prabhupada was lecturing, a boy came up and sat on the dais beside him. The boy faced out toward the audience and interrupted Prabhupada: “I got something to say. I want to say what I have to say now.” The devotees in the audience looked up, astonished, while the boy began talking incoherently.

Then Prabhupada picked up his karatalas: “All right, let us have kirtana.” The boy sat in the same place throughout the kirtana, looking crazily, sometimes menacingly, at Prabhupada. After half an hour the kirtana stopped.

Prabhupada cut an apple into small pieces, as was his custom. He then placed the paring knife and a piece of apple in his right hand and held his hand out to the boy. The boy looked at Prabhupada, then down at the apple and the knife. The room became silent. Prabhupada sat motionless, smiling slightly at the boy. After a long, tense moment, the boy reached out. A sigh rose from the audience as the boy chose the piece of apple from Prabhupada’s open hand.

Haridasa: I used to watch how Swamiji would handle things. It wasn’t easy. To me, that was a real test of his powers and understanding—how to handle these people, not to alienate or antagonize or stir them up to create more trouble. He would turn their energy so that before they knew it they were calm, like when you pat a baby and it stops crying. Swamiji had a way of doing that with words, with the intonation of his voice, with his patience to let them carry on for a certain period of time, let them work it out, act it out even. I guess he realized that the devotees just couldn’t say, “Listen, when you come to the temple you can’t behave this way.” It was a delicate situation there.

Often someone would say, “I am God.” They would get an insight or hallucination from their drugs. They would try to steal the spotlight. They wanted to be heard, and you could feel an anger against the Swami from people like that. Sometimes they would speak inspired and poetic for a while, but they couldn’t sustain it, and their speech would become gibberish. And the Swami was not one to simply pacify people. He wasn ‘t going to coddle them. He would say, “What do you mean? If you are God, then you have to be all-knowing. You have to have the attributes of God. Are you omniscient and omnipotent?” He would then name all the characteristics that one would have to have to be an avatara, to be God. He would rationally prove the person wrong. He had superior knowledge, and he would rationally explain to them, “If you are God, can you do this? Do you have this power?”

Sometimes people would take it as a challenge and would try to have a verbal battle with the Swami. The audience’s attention would then swing to the disturbing individual, the person who was grabbing the spotlight. Sometimes it was very difficult. I used to sit there and wonder, “How is he going to handle this guy? This one is really a problem. ” But Swamiji was hard to defeat. Even if he couldn’t convince the person, he convinced the other people in the crowd so that the energy of the room would change and would tend to quiet the person. Swamiji would win the audience by showing them that this person didn’t know what he was talking about.

So Swamiji would remove the audience rather than the person. He would do it without crushing the person. He would do it by superior intelligence, but also with a lot of compassion. He had the sensitivity not to injure a person psychologically or emotionally, so that when the person sat down and shut up, he wouldn’t be doing it in defeat or anger—he wouldn’t be hurt. He would just be outwitted by the Swami. When I saw the Swami do these things, then I realized he was a great teacher and a great human being.

(To be continued.)

Leave a Reply