Questions at Harvard Divinity School

Recently Professor Harvey Cox of Harvard University invited Subhananda dasa, a Hare Krsna devotee, to give three talks on the traditional role of the guru. Later the talking went on, between Professor Cox and his divinity students and their guest.

Student: The idea of “spiritual guide” or “spiritual master” is not exclusive to the Indian spiritual tradition, as you know. It’s found, in varying degrees of formality, in a wide spectrum of religious and cultural contexts: the Christian abbot or prior, the Jewish rabbi, the Zen roshi, and so on. Yet most people in the West seem apprehensive about the idea of submission to a spiritual guide. Why would you say this is?

Subhananda dasa: It’s due to a lack of interest in spiritual life. We live in a society that is materially oriented, so most people simply aren’t interested. This lack of interest in spirituality comes from our modern skepticism—our disbelief in the very notion of an absolute, perfect Truth. Most people—if they have any interest in philosophy or religion at all—tend to be relativists: “Everyone has his own truth.” So if there’s really no ultimate, objective, absolute Truth—if all is relative and subjective—then the idea of a guru, one who teaches Truth, becomes meaningless. And so we view gurus as merely people propagating their own or someone else’s relative concept of truth or reality.

Student: Also, most people are reluctant to accept the premise of human perfectibility. Even though there may be objective truth, they say, human nature is so terribly fallible—and therefore no one person can perceive truth in full.

Subhananda dasa: Yes. Absolute Truth, or God, appears so infinite, transcendent, or esoteric that it must be beyond our human powers to perceive it. So we think that no one can achieve perfect realization of Truth. We accept the idea of “teacher” only in a limited sense. One person, we think, may be able to tell us something of his own relative insights about relative truths. But anyone who reportedly possesses perfect knowledge of truth has to be immediately written off as a charlatan. We see this skepticism in the media’s stereotypes—”the guru”: a skinny old fellow wearing long flowing hair and a beard, dispensing cryptic aphorisms and cosmic riddles, and milking his followers for all they’re worth.

Student: I think that—perhaps out of pride—some people dislike the very idea of submission.

Subhananda dasa: Yes. We’d rather be in the position of teacher than that of student. Submission to a teacher implies an admission that I need instruction and guidance. And this is humbling. Most of us will submit to another person for guidance only as a last resort, when all our own wisdom has failed.

Student: But then, we all know that authority figures can become corrupt. All of us have, I suppose, experienced disappointment with authority figures—parents, teachers, politicians, clergy. I think we’re leery of any guru because he may be corrupt.

Subhananda dasa: Unfortunately, that fear is well founded. For every genuine guru, there are plenty of others who are not qualified, not genuine, whose motives are questionable. And for sure, some are outright charlatans and conmen. Often the problem is, “Power corrupts.” And when a guru is invested, whether by tradition or by self-pronouncement, with absolute power, too often, “Absolute power corrupts absolutely.” If a person’s motives in becoming someone else’s spiritual mentor are even slightly tainted with self-serving, quite likely he’ll turn into an exploiter. So one has to be wary. There are bona fide gurus. But : to find a bona fide guru one has to be a genuine seeker.

Student: Why do so many people seem to fall in with gurus of such questionable qualifications or motives?

Subhananda dasa: It’s because most self-styled seekers don’t really want a genuine traditional guru. They don’t want spiritual life strongly enough to make the necessary sacrifices. A genuine guru will require real personal surrender and real renunciation of worldliness. Most people simply don’t want to go that far. They want a guru who will make few demands and provide a cheap artificial “high.” Another thing is that hardly any gurus on the American scene talk about the traditional texts that provide criteria by which would-be followers could judge a teacher’s authenticity. In many cases, I’m sure, the gurus do this quite consciously. Some teachers go so far as denying the importance of the traditional texts and arguing that they themselves can provide the spiritual experience that the scriptures can only describe. This is a ploy to save themselves from being exposed. The followers are left with no criteria for judging the authenticity of their guru—except, of course, the guru’s own criteria. Anyone who knows the Indian spiritual tradition through the texts of the tradition can see through all this. But many followers are spiritually illiterate, ignorant of the depth and richness of the traditions their gurus claim to represent.

Under the banner of “experience” they imagine that analytical thinking is a waste of time—and so they have no grasp of any spiritual realities other than vague concepts like “the light,” “the spirit,” “love,” “the One,” and so on. You may consider this a bit of an exaggeration. If you do, go and see for yourselves. Talk with the followers of some gurus. You’ll be surprised.

Student: I think what you’ve said about inauthentic gurus has been helpful. I’d like to hear you speak a little more about the concept of guru in the ideal, as articulated in your own tradition.

Subhananda dasa: Well, the basic thing about a guru is that he is fully conversant with the science of the Absolute Truth. Also, a genuine guru is a fully self-realized soul. He is free from illusion. He knows himself as an eternal, spiritual being, and thus he no longer identifies himself with materiality. He knows the Absolute Truth as the source and essence of everything. And his knowledge isn’t theoretical or speculative; it’s based on direct perception of reality. He experiences truth directly, not merely in theory. He isn’t just a philosopher or theologian, but a mystic. He has experienced, and is experiencing, that of which he speaks.

And not only does the realized guru know the truth. He loves the truth. In its original sense, the term philosopher means “one who loves truth.” So one might say that the spiritual master is the ideal philosopher. Nor is it a mere concept or idea, however grandiose or sublime, that he loves. It is the Personal Truth, God, who elicits his deepest devotional sentiments.

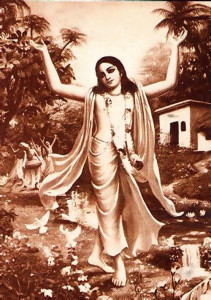

There are, of course, many interpretations of the nature and function of the guru, even within the Indian spiritual tradition. But rather than try to provide a survey, I’m speaking from the viewpoint of India’s chief and most influential theistic tradition, that of Vaisnavism, represented by such seminal thinkers as Ramanuja, Madhva, and Sri Caitanya.

Student: Earlier you spoke of the guru’s asceticism …

Subhananda dasa: Yes. This is another classical characteristic of a genuine guru. He has renounced the desire for material acquisition and gratification. Because he is free of ahankara, false ego, he isn’t physically or mentally self-indulgent. In other words, it’s not enough for one to know oneself to be different from one’s material body merely in theory. One has to understand his spiritual identity through direct realization.

And one who directly realizes his spiritual identity renounces those objects, those pleasures, that have to do with the temporal body. He realizes that just as the body is temporary, so its possessions and its pleasures are also temporary and therefore of no real, ultimate significance. Compared to the sublime pleasure he gets from his devotional service to Lord Krsna, all mundane pleasures appear dull and lifeless. This renunciation or asceticism can come only from real spiritual advancement. That’s why Srila Rupa Gosvami tells us, “Only a spiritually advanced person who can tolerate the urge to speak, the mind’s demands, the actions of anger, and the urges of the tongue, the belly, and the genitals is qualified to take the position of guru.” If someone has taken the position of guru and yet we see he’s still attached to materialism, this should give us pause.

Student: So practice is at least as important as precept?

Subhananda dasa: Yes. If the guru himself is not renounced—if he is still addicted to worldly activities and gratification—how will he succeed in freeing others from egoism and illusion? He himself must set the highest example. The guru is also called acarya—one who teaches by personal example. In other words, he himself lives by the knowledge he teaches. His actions, his words, his entire disposition reflect the sublime truth of which he speaks. His actions set an example for others to follow. His very presence can, if one is a little sensitive, soften the heart, elevate the feelings, and inspire sublime action.

Student: The qualifications for the guru that you’ve discussed so far—that he must be spiritually realized, that he must be materially renounced, and that he must set a high example—sound like general criteria for holiness. What uniquely distinguishes a person as a guru over and above a holy man?

Subhananda dasa: The obvious distinguishing factor is that the guru teaches. Not only is he a holy man, but he also makes others holy. This means compassion. He isn’t content with his own spiritual advancement, liberation, or salvation. He desires these things for others. In fact, this compassion is the real symptom of spirituality.

It’s important to note how the guru transmits knowledge to his disciple. There’s a popular misconception that the guru’s enlightenment of his disciple is a kind of magical feat whereby he magically injects spiritual knowledge into his disciple as if surcharging him with an electrical current. In reality, the guru explains everything to the disciple in accordance with logic and reason, as well as scriptural authority and tradition.

Student: Earlier, you were speaking about how to be sure of the validity of the knowledge the guru teaches, and you were tying that in with historical disciplic succession.

Subhananda dasa: This is a crucial point. There has to be a test for validity. Nowadays, everyone considers himself a guru, in the sense that everyone instinctively assumes that he’s seeing things as they really are. We draw upon the vast and murky data of our ordinary daily sense perceptions and mental impressions, and we form broad conclusions about the nature of things. But because one person’s sensory and mental impressions differ vastly from any other person’s, we come to vastly differing conclusions. A multitude of individuals, a multitude of weltanschauungs. We all think we’re our own guru. But clearly anyone who thinks he’s his own guru has a fool for a disciple.

The idea of a guru presumes the existence, the reality, of perfect objective knowledge—knowledge that can be directly perceived, if only we have the eyes to see it. Within the broad tradition that I’m taking part in, perfect and infallible knowledge is called veda—divine, eternal wisdom, preserved through oral tradition and later compiled in the form of the Vedic scriptures. Traditionally, Vedic knowledge is transmitted through what is called parampara, disciplic succession. The knowledge is carefully preserved and passed down from master to disciple, generation after generation. In other words, the guru. has the sacred duty to transmit Vedic knowledge as it is, without subjective taint or speculative interpretation.

Professor Cox: I’d like to raise in a friendly way what I think might be an interesting contrast—not in this case, I think, between the Hindu tradition and the Christian, but between what might be referred to as the lineage and the antilineage elements within any particular religious tradition. I think that in Christianity one finds examples of both lineage and antilineage, or disciplic and antidisciplic, understandings. There’s the concept of apostolic succession, which the Pope is said to represent, and many churches are based on this notion of disciplic succession.

There are, however, and I think also stemming from Jesus, antilineage, anti-disciplic visions of truth. The underlying thought here is that a lineage can become corrupt and often is corrupt. In fact, many of them have within their very structure the possibility of corruption. And therefore God sometimes appears in human society as a critic of lineage rather than its perpetuator. When Jesus criticizes the existing lineage of his time, he says, “You say you have Abraham as your father, but I tell you that God is able to raise up out of the stones children of Abraham.” He affiliates himself with John the. Baptist, who founded what you might call an antilineage movement. And also, interestingly enough, we have the example of St. Paul, who was a kind of epitome in the early Christian period of the antilineage disciplic notion. That is, he had a direct revelation from God and Christ and carefully did not seek legitimization from the early disciples. So, maybe you’d like to respond to this theme—the tension between the disciplic transmission and the … let’s call it the charismatic or visionary revelation of truth, which is often antidisciplic.

Subhananda dasa: You’re certainly correct in pointing out that a lineage can and does become corrupt. Lineages become weak or cease to function altogether. Religious history provides many examples of this, for sure. But it is important to understand Vaisnava disciplic succession as not merely historical but revelatory. That is, it by no. means precludes charismatic or visionary revelation of truth. Succession does not necessarily imply merely mechanical transmission of dogma. The guru is no mere pedantic functionary. With each link in the disciplic .chain, the eternal Vedic knowledge comes to life. It becomes real and dynamic through the guru’s own spiritual vitality. He realizes truth and he transmits the fruits of that realization, including the very process through which his disciple can himself achieve realization. Krsna tells Arjuna in the Gita, “The self-realized soul can impart knowledge unto you because he has seen the truth.” It is further understood that the Lord, in His form as the indwelling witness and guide, the Supersoul, the Paramatma, is forever revealing spiritual understanding within the heart of His pure devotee. So disciplic succession is a revelatory function, although that function remains intact only so long as the links of the chain are strong.

But, because for one reason or another a disciplic succession may be corrupted or lose its spiritual vitality, God will intercede, either personally or through an agent. You gave the example of Jesus Christ, who criticized the lineage existing in his time. But it seems to me that what he was criticizing was not the notion of lineage per se, but the corruption of lineage, or the decadence or misuse of lineage, or simply the limitations of a particular lineage. Catholics, at any rate, would argue that Jesus himself established a new lineage, that of the apostolic succession, although, as you imply, Protestant thinking would tend to be antilineage in that respect. In Vaisnava understanding, the Lord can and does intercede historically when a tradition has been corrupted or lost, or is in need of revitalization. In Bhagavad-gita, Lord Krsna Himself explained to Arjuna that with the ancient disciplic succession now broken, the eternal science of yoga had become lost, and therefore it was necessary for Him to personally present again this science to His disciple, Arjuna, through the Gita. Disciplic successions can degrade into archaic orthodoxy, but they don’t have to.

Student: If the guru is primarily a transmitter of Vedic knowledge, can’t one simply guide one’s life in terms of that scriptural knowledge, without having to associate himself with a guru? Why can’t one deal directly with the scripture?

Subhananda dasa: Adherence to Vedic scripture without the direct, practical guidance of a spiritual master is insufficient for spiritual advancement for a few reasons. First, Vedic literature describes the Absolute Truth from various angles and prescribes a variety of paths to that Truth. The spiritual master knows the particular mentality of each disciple and instructs him personally, in a manner appropriate to his mentality. The example is given that a pharmacy may contain thousands of medicines, but one requires a doctor who can prescribe the appropriate medicine for the particular ailment. Second, the spiritual aspirant benefits from the personal example of a perfected soul. Because the guru personally exemplifies Vedic wisdom, that wisdom becomes a tangible, real thing for the disciple.

Further, it’s not by the disciple’s own efforts, in the ultimate sense, that he advances on the spiritual path. It is by divine grace. The Lord’s blessings are delivered by the Lord’s representative, the spiritual master. A verse in the Svetasvatara Upanisad states, “Only unto those great souls who simultaneously have implicit faith in both the Lord and the spiritual master are all the imports of the Vedic knowledge automatically revealed.”

Student: I wonder if you could explain again the guru’s emissary function—what you referred to as his being an “external manifestation” of God?

Subhananda dasa: The authentic guru is God’s representative. He acts as the intermediary between the spiritual aspirant and God. The guru does not obstruct the soul’s approach to God. He facilitates it. While under the influence of maya, illusion, the unaided soul can neither perceive nor approach God directly. He makes this approach through the spiritual master. The disciple sees God, you might say, through his spiritual master—and this vision is really still direct. You may view a tree through your bedroom window, but your perception of the tree is still direct. What this means is that the guru must be “transparent”—a transparent medium for the disciple’s approach to God. The guru doesn’t take the disciple’s worship as his own, but he passes it on to God. God appears, as it were, through the agency of the guru to liberate the seeking soul. (To be continued.)

Leave a Reply