A Most Intense Presence

Some early followers drifted away, but many newcomers felt irresistibly drawn to Srila Prabhupada and his Krsna conscious Society.

by Srila Satsvarupa dasa Goswami

After weathering a near-fatal sea journey from India and a difficult winter on New York City’s Upper West Side and the Bowery, Srila Prabhupada had set up America’s first Krsna temple in the East Village. Now, as some of his early supporters began to fall away, new people joined him.

Don was a test of Swamiji’s tolerance. He had lived in the storefront for months, working little and not trying to change talking, he enunciated his words, as if he were reciting from a book. And he never used contractions. It wasn’t that he was intellectual, just that somehow he had developed a plan to abolish his natural dialect. Don’s speech struck as bizarre, like it might be the result of too many drugs. It gave him an air of being not an ordinary being. And he continually took marijuana, even after Swamiji had asked those who lived with him not to. Sometimes during the day his girl friend would join him in the storefront, and they would sit together talking intimately and sometimes kissing. But he liked the Swami. He even gave some money once. He liked living in the storefront, and Swamiji didn’t complain.

But others did. One day an interested newcomer dropped by the storefront and found Don alone, surrounded by the sharp aroma of marijuana. “You have been smoking pot? But the Swamiji doesn’t want anyone smoking here.” Don denied it: “I have not been smoking. You are not speaking the truth.” The boy then reached into Don’s shirt pocket and pulled out a joint, and Don hit him in the face. Several of the boys found out. They weren’t sure what was right: What would the Swami do? What do you do if someone smokes pot? Even though a devotee was not supposed to, could it be allowed sometimes? They put the matter before Swamiji.

Prabhupada took it very seriously, and he was upset, especially about the violence. “He hit you?” he asked the boy. “I will go down myself and kick him in the head.” But then Prabhupada thought about it and said that Don should be asked to leave. But Don had already left.

The next morning during Swamiji’s class, Don appeared at the front door. From his dais, Swamiji looked out at Don with great concern. But his first concern was ISKCON: “Ask him,” Prabhupada requested Roy, who sat nearby, “if he has marijuana—then he cannot come in. Our society…” Prabhupada was like an anxious father, afraid for the life of his infant ISKCON. Roy went to the door and told Don he would have to give up his drugs if he entered. And Don walked away.

Raphael was not interested in spiritual discipline. He was a tall young man with long, straight, brown hair who, like Don, tried to stay aloof and casual toward Swamiji. When Prabhupada introduced japa and encouraged the boys to chant during the day, Raphael didn’t go for it. He said he liked a good kirtana, but he wouldn’t chant on beads.

One time Swamiji was locked out of his apartment, and the boys had to break the lock. Swamiji asked Raphael to replace it. Days went by. Raphael could sit in the storefront reading Rimbaud, he could wander around town, but he couldn’t find time to fix the lock. One evening he opened the lockless door to the Swami’s apartment and made his way to the back room, where some boys were sitting, listening to Swamiji speak informally about Krsna consciousness. Suddenly Raphael spoke up, revealing his doubts and his distracted mind. “As for me,” he said, “I don’t know what’s happening. I don’t know whether a brass band is playing or what the heck is going on.” Some of the devotees tensed; he had interrupted their devotional mood. “Raphael is very candid,” Swamiji replied smiling, as if to explain his son’s behavior to the others.

Raphael finally fixed the lock, but one day after a lecture he approached the Swami, stood beside the dais, and spoke up, exasperated, impatient: “I am not meant to sit in a temple and chant on beads! My father was a boxer. I am meant to run on the beach and breathe in big breaths of air. . . .” Raphael went on, gesticulating and voicing his familiar complaints—things he would rather do than take up Krsna consciousness. Suddenly Prabhupada interrupted him in a loud voice: “Then do it! Do it!” Raphael shrank away, but he stayed.

Bill Epstein took pride in his relationship with the Swami—it was honest. Although he helped the Swami by telling people about him and sending them up to see him in his apartment, he felt the Swami knew he’d never become a serious follower. Nor did Bill ever mislead himself into thinking he would be serious. But Prabhupada wasn’t content with Bill’s take-it-or-leave-it attitude. When Bill would finally show up at the storefront again after spending some days at a friend’s place, only to fall asleep with a blanket wrapped over his head during the lecture, Prabhupada would just start shouting so loud that Bill couldn’t sleep. Sometimes Bill would ask a challenging question, and Prabhupada would answer and then say, “Are you satisfied?” and Bill would look up dreamily and answer, “No!” Then Prabhupada would answer it again more fully and say louder, “Are you satisfied’?” and again Bill would say no. This would go on until Bill would have to give in: “Yes, yes, I am satisfied.”

But Bill was the first person to get up and dance during a kirtana in the storefront. Some of the other boys thought he looked like he was dancing in an egotistical, narcissistic way, even though his arms were outstretched in a facsimile of the pictures of Lord Caitanya. But when Swamiji saw Bill dancing like that, he looked at Bill with wide-open eyes and feelingly expressed appreciation: “Bill is dancing just like Lord Caitanya.”

Bill sometimes returned from his wanderings with money, and although it was not very much, he would give it to Swamiji. He liked to sleep at the storefront and spend the day on the street, returning for lunch or kirtanas or a place to sleep. He used to leave in the morning and go looking for cigarettes on the ground. To Bill, the Swami was part of the hip movement and had thus earned a place of respect in his eyes as a genuine person. Bill objected when the boys introduced signs of reverential worship toward the Swami (starting with their giving him an elevated seat in the temple), and as the boys who lived with the Swami gradually began to show enthusiasm, competition, and even rivalry among themselves, Bill turned from it in disgust. He allowed that he would go on just helping the Swami in his own way, and he knew that the Swami appreciated whatever he did. So he wanted to leave it at that.

Carl Yeargens had helped Prabhupada in times of need. He had helped with the legal work of incorporating ISKCON, signed the ISKCON charter as a trustee, and even opened his home to Swamiji when David had driven him from the Bowery loft. But those days when he and Eva had shared their apartment with him had created a tension that had never left. He liked the Swami, he respected him as a genuine sannyasi from India, but he didn’t accept the conclusions of the philosophy. The talk about Krsna and the soul was fine, but the idea of giving up drugs and sex was carrying it a little too far. Now Prabhupada was settled in his new place, and Carl felt he had done his part and was no longer needed. Though he had helped Prabhupada incorporate his International Society for Krishna Consciousness, he didn’t want to join it.

Carl found the Second Avenue kirtanas too public, not like the more intimate atmosphere he had enjoyed with the Swami on the Bowery. Now the audiences were larger, and there was an element of wild letting loose that they had never had on the Bowery. Like some of the other old associates, Carl felt reluctant to join in. Compared to the Second Avenue street scene, the old meetings in the fourth-floor Bowery loft had seemed more mystical, like secluded meditations.

Carol Bekar also preferred a more sedate kirtana. She thought people were trying to take out their personal frustrations by the wild singing and dancing. The few times she did attend evening kirtanas on Second Avenue were “tense moments.” One time a group of teenagers had come into the storefront mocking and shouting, “Hey! What the hell is this!” She kept thinking that at any moment a rock was going to come crashing through the big window. And anyway, her boyfriend wasn’t interested.

Robert Nelson, Prabhupada’s old uptown friend, never deviated in his good feelings for Prabhupada, but he always went along in his own natural way and never adopted any serious disciplines. Somehow, almost all of those who had helped Prabhupada uptown and on the Bowery did not want to go further once he began a spiritual organization, which happened almost immediately after he moved into 26 Second Avenue. New people were coming forward to assist him, and Carl, Carol, and others like them felt that they were being replaced and that their obligation toward the Swami was ending. It was a kind of changing of the guard. Although the members of the old guard were still his well-wishers, they began to drift away.

* * *

Bruce Scharf had just graduated from New York University and was applying for a job. One day an ex-roommate told him about the Swami he had visited down on Second Avenue. “They sing there,” his friend said, “and they have this far-out thing where they have some dancing. And Allen Ginsberg was there.” The Swami was difficult to understand, his friend explained, and besides that, his followers recorded his talks on a tape recorder. “Why should he have a big tape recorder? That’s not very spiritual.” But Bruce became interested.

He was already a devotee of Indian culture. Four years ago, when he was barely twenty, Bruce had worked during the summer as a steward aboard an American freighter and gone to India, where he had visited temples, bought pictures of Siva and Ganesa and books on Gandhi, and felt as if he were part of the culture. When he returned to NYU., he read more about India and wrote a paper on Gandhi for his history course. He would eat in Indian restaurants and attend Indian films and music recitals, and he was reading the Bhagavad-gita. He had even given up eating meat. He had plans of returning to India, taking some advanced college courses, and then coming back to America to teach Eastern religions. But in the meantime he was experimenting with LSD.

Chuck Barnett was eighteen years old. His divorcee mother had recently moved to Greenwich Village, where she was studying psychology at NYU. Chuck had moved out of his mother’s apartment to one on Twelfth Street on the Lower East Side, in the neighborhood of Allen Ginsberg and other hip poets and musicians. He was a progressive jazz flutist who worked with several professional groups in the city. He had been practicing hatha-yoga for six years and had recently been experimenting with LSD. He would have visions of lotuses and concentric circles, but after coming down, he would become more involved than ever in sensuality. A close friend of Chuck’s had suddenly gone homosexual that summer, leaving Chuck disgusted and cynical. Someone told Chuck that an Indian swami was staying downtown on Second Avenue, so he came one day in August to the window of the former Matchless Gifts store.

Steve Guarino, the son of a New York fireman, had grown up in the city and graduated from Brooklyn College in 1961. Influenced by his father, he had gone into the Navy, where he had tolerated two years of military routine, always waiting for the day he would be free to join his friends on the Lower East Side. Finally, a few months after the death of President Kennedy, he had been honorably discharged. Without so much as paying a visit to his parents. he had headed straight for the Lower East Side, which by then appeared vividly within his mind to be the most mystical place in the world. He was writing stories and short novels under the literary influence of Franz Kafka and others, and he began to take LSD “to search and experiment with consciousness.” A Love Supreme, a record by John Coltrane, the jazz musician, encouraged Steve to think that God actually existed. Just to make enough money to live, Steve had taken a job with the welfare office. One afternoon during his lunch hour, while walking down Second Avenue, he saw that the Matchless Gifts store had a small piece of paper in the window, announcing, “Lectures in Bhagavad Gita, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami.”

Chuck: I finally found Second Avenue and First Street, and I saw through the window that there was some chanting going on inside and some people were sitting up against the wall. Beside me on the sidewalk some middle-class people were looking in and giggling. I turned to them, and with my palms folded I asked, “Is this where a swami is?” They giggled and said, “Pilgrim, your search has ended. “I wasn’t surprised by this answer, because I felt it was the truth.

Bruce: I was looking for Hare Krsna. I had left my apartment and had walked over to Avenue B when I decided to walk all the way down to Houston Street. When I came to First Street, I turned right and then, walking along First Street, came to Second Avenue. All along First Street I was seeing these Puerto Rican grocery stores, and then there was one of those churches where everyone was standing up, singing loudly, and playing tambourines. Then, as! walked further along First Street, I had the feeling that I was leaving the world, like when you’re going to the airport to catch a plane. I thought, “Now I’m leaving a part of me behind, and I’m going to something new.”

But when I got over to Second Avenue, I couldn’t find Hare Krsna. There was a gas station, and then I walked past a little storefront, but the only sign was one that said Matchless Gifts. Then I walked back again past the store, and in the window I saw a black-and-white sign announcing a Bhagavad-gita lecture. I entered the storefront and saw a pile of shoes there, so I took off my shoes and came in and sat down near the back.

Steve: I had a feeling that this was a group that was already established and had been meeting for a while. I came in and sat down on the floor, and a boy who said his name was Roy was very courteous and friendly to me. He apparently had already experienced the meetings. He asked my name, and I felt at ease.

Suddenly the Swami entered through the side door. He wore a saffron dhoti but no shirt, just a piece of cloth like a long sash, tied across his right shoulder and leaving his arms, his left shoulder, and part of his chest bare. When I saw him I thought of the Buddha.

Bruce: There were about fifteen people sitting on the floor. One man with a big beard sat up by the front on the right-hand side, leaning up against the wall. After some time the door on the opposite side opened, and in walked the Swami. When he came in, he turned his head to see who was in his audience. And then he stared right at me. Our eyes met. It was as if he were studying me. In my mind it was like a photograph was being taken of Swamiji looking at me for the first time. There was a pause. Then he very gracefully got up on the dais and sat down and took out a pair of hand cymbals and began a kirtana. The kirtana was the thing that most affected me. It was the best music I’d ever heard. And it had meaning. You could actually concentrate on it, and it gave you some joy to repeat the words “Hare Krsna ” I immediately accepted it as a spiritual practice.

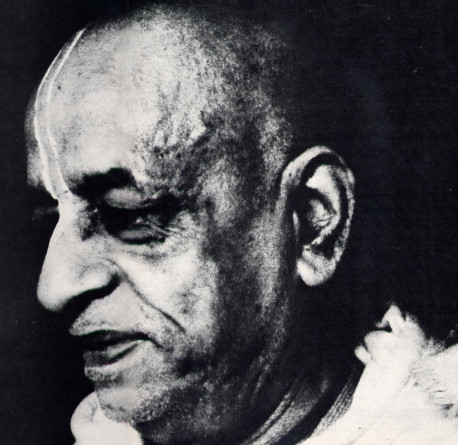

Chuck: I entered the storefront, and sitting on a grass mat on the hard floor was a person who seemed at first to be neither male nor female. but when he looked at me I couldn’t even look him straight in the eyes, they were so brilliant and glistening. His skin was golden with rosy cheeks, and he had large ears that framed his face. He had three strands of beads—one which was at his neck, one a little longer, and the other down on his chest. He had a long forehead, which rose above his shining eyes, and there were many furrows in his brow. His arms were slender and long. His mouth was rich and full, and very dark and red and smiling, and his teeth were brighter than his eyes. He sat in a cross-legged position that I had never seen before in any yoga book and had never seen any yogi perform. It was a sitting posture, but his right foot was crossed over the thigh and brought back beside his left hip, and one knee rested on the other directly in front of him. His every expression and gesture was different from those of any other personality I had ever seen, and I sensed that they had meanings that I did not know, from a culture and a mood that were completely beyond this world. There was a mole on his side and a peculiar callus on his ankle, a round callus similar to what a karate expert develops on his knuckle. He was dressed in unhemmed cloth, dyed saffron. Everything about him was exotic, and his whole effulgence made him seem to be not even sitting in the room but projected from some other place. He was so brilliant in color that it was like a technicolor movie, and yet he was right there. I heard him speaking. He was sitting right there before me, yet it seemed that if I reached out to touch him he wouldn’t be there. At the same time, seeing him was not an abstract or subtle experience but a most intense presence.

After their first visit to the storefront. Chuck, Steve, and Bruce each got an opportunity to see the Swami upstairs in his apartment.

Steve: I was on my lunch hour and had to be back in the office very soon. I was dressed in a summer business suit. I had planned it so that I had just enough time to go to the storefront and buy some books, then go to lunch and return to work. At the storefront, one of the Swami’s followers said that I could go up and see the Swami. I went upstairs to his apartment and found him at his sitting place with a few boos. I must have interrupted what he was saying, but I asked him if I could purchase the three volumes of the Srimad-Bhagavatam. One of the devotees produced the books from the closet opposite Swamiji’s seat. I handled the books—they were a very special color not usually seen in America, a reddish natural earth, like a brick-and I asked him how much they cost. Six dollars each, he said. I took twenty dollars out of my wallet and gave it to him. He seemed the only one to ask about the price of the books or give the money to, because none of the others came forward to represent him. They were just sitting back and listening to him speak.

“These books are commentaries on the scriptures?” I asked, trying to show that I knew something about books. Swamiji said yes, they were his commentaries. Sitting, smiling, at ease. Swamiji was very attractive. He seemed very strong and healthy. When he smiled, all his teeth were beautiful, and his nostrils flared aristocratically. His face was full and powerful. He was wearing an Indian cloth robe, and as he sat cross-legged, his smooth-skinned legs were partly exposed. He wore no shirt, but the upper part of his body was wrapped with an Indian cloth shawl. His limbs were quite slender, but he had a protruding belly.

When I saw that Swamiji was having to personally handle the sale of books, I did not want to bother him. I quickly asked him to please keep the change from my twenty dollars. I took the three volumes without any bag or wrapping and was standing, preparing to leave, when Swamiji said, “Sit down,” and gestured that I should sit opposite him like the others. He had said “Sit down” in a different tone of voice. It was a heavy tone and indicated that now the sale of the books was completed and I should sit with the others and listen to him speak. He was offering me an important invitation to become like one of the others, who I knew spent many hours with him during the day when I was usually at my job and not able to come. I envied their leisure in being able to learn so much from him and sit and talk intimately with him. By ending the sales transaction and asking me to sit, he assumed that I was in need of listening to him and that I had nothing better in the world to do than to stop everything else and hear him. But I was expected back at the office. I didn’t want to argue, but I couldn’t possibly stay. “I’m sorry. I have to go.” I said definitely. “I’m only on my lunch hour.” As I said this. I had already started to move for the door, and Swamiji responded by suddenly breaking into a wide smile and looking very charming and very happy. He seemed to appreciate that I was a working man, a young man on the go. I had not come by simply because I was unemployed and had nowhere to go and nothing to do. Approving of my energetic demeanor, he allowed me to take my leave.

Chuck: One of the devotees in the storefront invited me upstairs to see the Swami in private. I was led out of the storefront into a hallway and suddenly into a beautiful little garden with a picnic table, a birdbath, a birdhouse, and flower beds. After we passed through the garden, we came to a middle-class apartment building. We walked up the stairs and entered an apartment which was absolutely bare of any furniture-just white walls and a parquet floor. He led me through the front room and into another room, and there was the Swami, sitting in that same majestic spiritual presence on a thin cotton mat, which was covered by a cloth with little elephants printed on it, and leaning back on a pillow which stood against the wall.

One night Bruce walked home with Wally, and he told Wally about his interest in going to India and becoming a professor of Oriental literature. “Why go to India?” Wally asked, “India has come here. Swamiji is teaching us these authentic things. Why go to India?” Bruce thought Wally made sense, so he resolved to give up his long-cherished idea of going to India, at least as long as he could go on visiting the Swami.

Bruce: I decided to go and speak personally to Swamiji, so I went to the storefront. I found out that he lived in an apartment in the rear building. A boy told me the number and said I could just go and speak with the Swami. He said, “Yes, just go.” So I walked through the storefront, and there was a little courtyard where some plants were growing. Usually in New York there is no courtyard, nothing green, but this was very attractive. And in that courtyard there was a boy typing at a picnic table, and he looked very spiritual and dedicated. I hurried upstairs and rang the bell for apartment number 2C. After a little while the door opened, and it was the Swami. “Yes,” he said. And I said, “I would like to speak with you. “He opened the door wider and stepped back and said, “Yes, come.” We went inside together into his sitting room and sat down facing each other. He sat behind his metal trunk-desk on a very thin mat which was covered with a woolen blanketlike cover that had frazzled ends and elephants decorating it. He asked me my name and I told him it was Bruce. And then he remarked. ‘Ah. In India, during the British period, there was one Lord Bruce.” And he said something about Lord Bruce being a general and engaging in some campaigns.

I felt that I had to talk to the Swami—to tell him my story—and I actually found him interested to listen. It was very intimate, sitting with him in his apartment, and he was actually wanting to hear about me.

While we were talking, he looked up past me, high up on the wall behind me, and he was talking about Lord Caitanya. The way he looked up, he was obviously looking at some picture or something, but with an expression of deep love in his eyes. I turned around to see what made him look like that. Then I saw the picture in the brown frame: Lord Caitanya dancing in kirtana.

(To be continued)

Leave a Reply