As the most elevated species,

we human beings should have something to show for it.

by Mathuresa Dasa

Last summer I spent an afternoon at the Philadelphia Zoo with my two-year-old son, Uttama. It was a hot August day, and as I carried Uttama from cage to cage, from the elephant compound to the lion house to the bird sanctuary, I began to wish I had heeded my wife’s advice to bring along the stroller. “Why bring the stroller?” I had replied. “He knows how to walk.”

He certainly does know how to walk (and run and jump and climb), but like most two-year-olds, he usually heads in the wrong direction, toward whatever is most interesting—and dangerous. Spotting the elephants, he wriggled out of my arms and ran up to the low fence around the moat that separated them from us. I apprehended him just as he began to scale the fence, and I explained that we were supposed to look at the animals, not play with them. He grudgingly complied, and stood for a few minutes watching his would-be playmates and occasionally turning to me to exclaim, “B-i-i-g ones!”

I watched too, wondering what these “big ones” thought about being caged, with crowds of human creatures gawking at them. And not to speak of being caged within a zoo, what was it like to be caged within such a body? As a student of the Bhagavad-gita As It Is, I understood that every living creature—elephant, human being, or whatever—is not the physical body but is the eternal soul within the body. The soul activates the body just as a man “activates” his clothing. A body can’t move without the soul any more than a suit of clothes can get up and walk.

One amazing thing about the soul is that although it is extremely small (one ten-thousandth the size of the tip of a hair, the Svetasvatara Upanisad says), it activates huge bodies, like elephants and whales; microscopic bodies, like germs and viruses; and everything in between. The tiny soul spreads consciousness throughout the body just as the sun spreads its light throughout the sky.

So these elephants loitering before us in the August heat were in fact tiny spirit souls inside huge, gray, four-legged bodies. Since their senses, mind, and intelligence were different from mine, they saw, heard, smelled, tasted, felt, and thought about things in a different way. I, for instance, couldn’t tell offhand the difference between the males and the females. But the elephants, I assumed, could not only tell the difference, but found their mates quite comely. And the elephants would prefer different foods than I, although we probably could have shared a bag of peanuts. As individual spirit souls, all living beings are qualitatively the same, but when the consciousness of the soul “filters” through a particular body, it takes on particular qualities and activities.

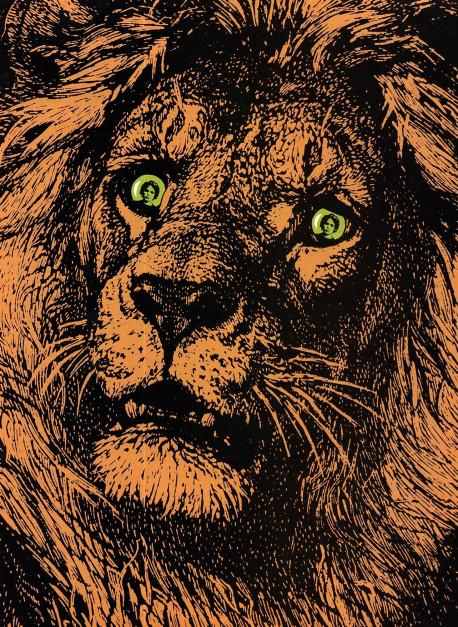

Uttama and I next visited the lion house. When I told Uttama that the lioness asleep in a cage outside the main entrance was a “big kitty,” he stared in disbelief. Back home Uttama was pretty good friends with the Siamese cat next door, although it had scratched him once or twice. But what if, he seemed to be thinking, one of these moved into the neighborhood?

Inside, visitors crowded up to a railing in front of a row of three cages on one side of a large room. On the opposite side, people sat on bleachers provided by some thoughtful zoo managers. Lions were a big attraction.

Edging forward to get a better look, I saw two more lionesses and one lion, all three pacing back and forth at the front of their cages. With Uttama in my arms, I stood and watched the lion as he reached one end of his cage, wheeled around, and shook his golden mane. We caught his eyes for the first time, and Uttama grabbed my shoulder and hid his face. I was also startled. Obviously this guy was hungry, and as he glared at us, his intentions, frustrated by only a few iron bars, were clear.

The lion’s features were so fierce that I had to remind myself that he too was a spirit soul. The Bhagavad-gita and other Vedic literatures explain that every soul is originally a pure, eternal servant of the Supreme Soul, the Personality of Godhead, Lord Krsna. But when the soul desires to forget his position as servant of Krsna and to become a lord himself, he falls into the material world, where he gets the opportunity to fulfill his desires in the various species.

The individual soul is accompanied during his sojourn in this world by the Super-soul (an expansion of Lord Krsna), who sits beside the individual soul in the bodies of all living creatures. The Vedic literature likens Krsna’s expansion as Supersoul to the “expansion” of the sun, which can shine down on the heads of millions of people and yet remain one. The Supersoul enters everyone’s heart and yet remains the one Supreme Lord. The embodied soul, of course, has forgotten his relationship with the Supersoul, or Krsna, but Krsna is never affected by forgetfulness. He remains with the tiny individual soul, witnessing his activities and fulfilling his desires.

The Supersoul fulfills our desires first of all by supplying us with a suitable body, A living entity with an intense desire to eat flesh may be provided with a lion’s body, which is equipped with sharp claws and teeth as well as the strength and speed to hunt and kill other animals. An elephant, on the other hand, while also very strong, is not suited to eating meat, but has the ability to enjoy himself by consuming great quantities of other foodstuffs. The Vedic literature informs us that there are 8,400,000 species of life and that each species is designed to afford the soul the opportunity to enjoy a particular kind of sense pleasure.

At the end of its life in one body, the soul is transferred, by the arrangement of the Supersoul, to another body to again take birth. The soul thus travels in the cycle of repeated birth and death from body to body and from species to species, evolving from aquatic life to plant life to animal life and, finally, to the human form. According to the Vedic literature, the Darwinian theory of evolution, which states that all species have evolved from one-celled organisms, is incorrect. The Vedas state that all 8,400,000 species have existed since the beginning of creation. What evolves is not the body, but the soul.

The Supersoul not only directs the movement of the soul from body to body but also directs all psychological processes. In the Gita Lord Krsna says: “I am seated in everyone’s heart, and from Me come remembrance, knowledge, and forgetfulness.” The lion, for example, has not only the strength and speed to hunt and kill but the necessary knowledge or intelligence as well. Understanding the desires of the living entity perfectly, the Supersoul grants him the type of intelligence needed to fulfill those desires. All embodied souls, including those in human bodies, are under the impression that they are acting independently and are accomplishing things on their own. Yet without intelligence from the Supersoul, no one can do anything.

So, as Uttama and I watched the lion pace back and forth in his cage, I thought of how the Supersoul was present in the lion’s heart along with the individual conditioned soul and of how He had supplied that soul with a particular kind of body and intelligence. Completely forgetful of his eternal spiritual nature (that also by the Supersoul’s grace), this soul was fully identifying with its lion’s body, seeing other animals, including us two-legged ones, as food.

We had been watching for five or ten minutes when I noticed two zoo employees pushing a two-wheeled cart down the aisle between the guard rail and the lion cages. When I saw that the cart was filled with rather slimy-looking reddish-brown meat, it occurred to me why the lion had appeared so hungry—it was lunch time! Although the lion’s glare had at first startled me, I now felt a little empathy, even though his “lunch” looked revolting.

The crowd of visitors pressed forward as the zoo-keepers flung big hunks of meat into the cages. Everyone in the bleachers stood. The lion, being the last in line, pawed the bars, shook his head, and let out an echoing roar. When his portion finally came flying through the bars, he snatched it up in his jaws and carried it triumphantly to the back of his cage.

While the lion and lionesses ate, my attention turned to the crowd of spectators. I had already tried to understand how the world looked through the eyes of an elephant or a lion and how the Supersoul was fulfilling their desires. So what about my fellow human beings, my fellow zoo-goers? I assumed that their outlook was much like mine, that they found the spectacle of the lion’s meal somewhat ghastly, although natural. Raw meat, everybody knows, is the proper food for a lion.

But weren’t most of the spectators meat-eaters themselves? Nearly everyone nowadays is. So perhaps they were identifying, if only slightly, with the big meat-eaters behind the bars. I couldn’t say for sure.

What was perfectly clear, however, was that while both the lions and the spectators were capable of eating meat, the lions were much better at it. This the crowd seemed to notice, too.

“Look! It’s going to gobble the whole thing!” said one lady, as a lioness downed a particularly large mouthful.

“Ripped it in two!” a boy in front of me squealed, as the lion tore into his meal.

The lion is fully equipped to devour raw flesh; even its digestive system is specially adapted for meat. Medical research has linked meat-eating by humans to cancer, kidney disease, and heart disease; but the lion suffers no such difficulties.

Observing lunch at the lion cages served to confirm the assertion of the Vedic literatures that meat-eating is only for animals. Not only is the human body ill-adapted to consuming flesh, but the killing of helpless creatures for the satisfaction of our bellies is unworthy of our human intelligence. The animal is a spirit soul like ourselves, an individual who, when slaughtered, suffers as much as we would. And the Supersoul is present in the animal’s heart as much as in ours. Knowing this, a human being should see each body as a residence for the Supreme Lord and should therefore avoid violence as far as possible.

It’s not that I felt the urge to convince the crowd around me that they should be vegetarian. After all, many animals—like Uttama’s friends the elephants—are vegetarian, so why should a human being feel particularly distinguished simply because he eats only fruits, vegetables, and grains? Besides, killing vegetable life is also violent, although less so than killing creatures who are higher on the evolutionary scale and therefore more acutely conscious of pain.

The special opportunity of human life isn’t to be vegetarian, but to understand the soul and the Supersoul—the individual self and the Supreme Lord. When human beings have knowledge of the soul and the Supersoul, they naturally avoid violence, both toward each other and toward those lower on the evolutionary scale.

Holding Uttama in my now-aching arms, with four-legged meat-eaters in front of me behind the bars and two-legged ones pressing in around me, I felt fortunate to be a member of the Krsna consciousness movement and doubly determined to continue helping the movement, in my own small way, to energetically distribute the Vedic science of self-realization (the science of the self and the Superself) to all parts of the world. Only if people come to understand the Krsna consciousness movement can they take full advantage of their human lives.

Leave a Reply