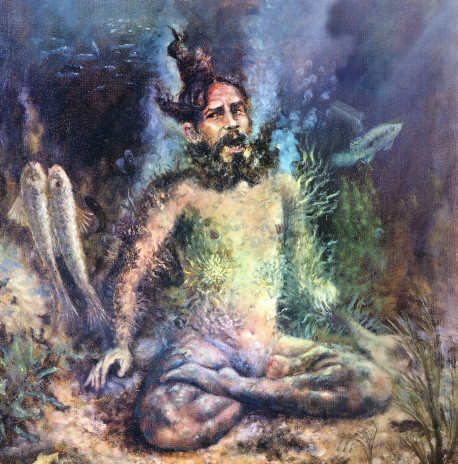

Ages ago, Saubhari Muni was so accomplished at yoga that he could meditate underwater. Everything was going fine, until . . .

by Mathuresa Dasa

To practice yoga, or silent meditation, you first of all need a secluded place. Traditionally, yogis have retired to Himalayan caves, to remote corners of dense, unexplored jungles, even to the depths of an ocean or river. The great yogi Saubhari Muni meditated for many years within the Yamuna River, with only the local fish for company. He was able to do so because he possessed many mystic powers—the sign of a true yogi—and could, like his aquatic companions, breathe underwater.

Why such extreme measures? Because the purpose of yoga is to withdraw the senses from all material engagements and fix the mind on the Supersoul (the form of the Supreme Personality of Godhead who dwells within the hearts of all living creatures). The aspiring yogi must completely abstain from even the thought of sex, reduce and regulate his eating and sleeping, and even restrict what he sees and hears. By extended, uninterrupted practice, the yogi transcends material nature and returns to the eternal spiritual world, the abode of Lord Krsna.

So don’t expect to properly practice the yoga of silent meditation in a city or a suburb or, for that matter, even in most rural areas; there are just too many distractions nowadays. You may practice sitting postures and breathing exercises, trying to improve your health, your aura, or your sexual prowess, and if you like you can call that yoga. But according to the ancient Vedic literature, the sourcebooks of yoga instruction, the purpose of yoga is to fully and continuously restrain the senses and fix the mind on the Supreme Person.

With this purpose fixed in his mind the yogi Saubhari Muni long ago entered the Yamuna River. Surely there he would be undisturbed. There were no attractive girls in designer jeans strutting along the river bottom, no ads for cigarettes, beer, or fashionable clothing to divert the attention, no business-wise yoga instructors crooning that their brand of spiritualism makes one a better executive or a better student or a better lover. No distractions whatsoever. Hardly a sound. Just Saubhari and the river. And the fish.

Poor Saubhari. He was a qualified, sincere, no-nonsense yogi, so well endowed with mystic powers that he could meditate underwater, yet his mind was diverted by a pair of fish. After many years of underwater meditation, Saubhari observed two fish copulating, and feeling the desire to enjoy sexual pleasure awaken within himself, he emerged from the river and went looking for a mate.

From this we can understand that meditational yoga, also known as astanga-yoga, although recommended in the Vedic literature as a means of ascending to the spiritual plane, is extremely difficult. We are all by nature active and pleasure-seeking. Most of us find it difficult to sit still even for a few minutes. We want to enjoy life by seeing, hearing, touching, walking, talking, and so on. To abruptly stop all these activities and meditate on God is almost unthinkable. Even such a highly qualified yogi as Saubhari Muni, who lived thousands of years before the rise of our noisy, polluted, fast-paced modern civilization, had a hard time of it.

So why would anyone attempt such a difficult form of yoga? Well, the aspiring transcendentalist, the yoga candidate, usually understands that bodily and mental activities alone cannot bring satisfaction. He has heard from Vedic authorities that we are not these material bodies but are eternal spirit souls dwelling within the body. The yogi wants to free himself from bodily encagement.

In the Bhagavad-gita Lord Krsna teaches that the body is a temporary vehicle for the soul and that after the demise of the body the soul takes a new body. The unenlightened soul transmigrates from body to body in the painful cycle of birth, old age, disease, and death, trying to enjoy life but is ultimately frustrated in every attempt. To become free from this cycle of misery and to experience transcendental bliss, the yogi is advised to reduce bodily activity and to meditate on the Supersoul, Lord Krsna. According to the Bhagavad-gita, the state of mind at death determines our next life. Thus, the yogi who passes away fully absorbed in meditation on Krsna attains an eternal, blissful body in the spiritual realm and never returns to take birth and die in this material realm.

In previous ages many yogis were able to perfect the process of astanga-yoga. In fact, Saubhari Muni himself, after exhausting his desire for material enjoyment, completely renounced the life of sensual pleasure, returned to his meditation, and attained perfection. In the present age, however, astanga-yoga is more or less impossible, and the Vedic literature recommends instead the path of bhakti-yoga, devotional service.

The purpose of bhakti-yoga is the same as that of astanga-yoga: to withdraw the senses from all material activities and to concentrate the mind in unswerving meditation on the Supreme Person. In bhakti-yoga, however, we actively use our senses in Krsna’s service. In particular, bhakti-yoga involves hearing—hearing about Krsna’s qualities and pastimes, about the activities of His incarnations and great devotees, and about the transcendental philosophy spoken by the Lord Himself in the Bhagavad-gita. The bhakti-yogi learns to see everything in relation to the Supreme Personality of Godhead, to see that the material universe is His creation. The bhakti-yogi also regularly meditates on the beautiful Deity form of the Lord in the temple. The bhakti-yogi can even employ his tongue in Krsna’s service—by tasting food offered to Krsna and by chanting His holy names.

In this way the bhakti-yogi is always active within the realm of devotional service. He attains the same result as the inactive astanga-yogi; but easily and naturally. The bhakti-yogi can live with his friends and family in the midst of modern civilization. In fact, many of the practices of bhakti-yoga are best performed in the company of other devotees—the more the merrier. Far from distracting, the association of devotees is an inspiration for the performance of devotional service. The serious astanga-yogi; however, must remain alone. and even then, as in the case of Saubhari, there is a chance of falling away from the path of austerity and renunciation.

The purpose of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) is to make the spiritual association of devotees (bhakti-yogis) available in every part of the world. ISKCON centers are open to anyone interested in hearing about the Supreme Personality of Godhead and rendering service to Him in the company of devotees. Aspiring yogis can thus attain perfection, unperturbed by the distractions of modern life.

Thank you for sharing. Very inspiring.

We are blessed and blessed to be a part of your family and much delighted We are being taken near to supreme God by Mahamantra under Yr guidance Stay blessed Hare krishna