Transcendental Commentary on the Issues of the Day

A Passage To The Real India

by Nayanabhirama dasa

Last year sensational news of tragedy from India twice shocked the world—first, the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi followed by mass murders and mayhem, then, hardly a month later, the catastrophic poisonous gas leak at the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal. Yet, despite these ghastly events, tourism to India has increased. Even before the U.S. State Department had lifted its brief advisory against travel to India, travel agents reported a mounting demand for brochures and bookings to India.

Last year sensational news of tragedy from India twice shocked the world—first, the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi followed by mass murders and mayhem, then, hardly a month later, the catastrophic poisonous gas leak at the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal. Yet, despite these ghastly events, tourism to India has increased. Even before the U.S. State Department had lifted its brief advisory against travel to India, travel agents reported a mounting demand for brochures and bookings to India.

Tragedies or no tragedies, India continues to lure the Western imagination by her exotic charms. In fact, the recent flood of movies set in India has deluged the West like a monsoon. In an article headlined “India, the Sudden Star,” one New York newspaper was prompted to write, “Now, suddenly India is everywhere; if a country could be described as a pop-culture star, India would be it.” The eagerly awaited “Festival of India,” a twelve-million-dollar, two-year-long cultural extravaganza—the largest cultural exchange ever assembled—scheduled to open in the U.S. later this year, shows that the trend of fascination with India gives no sign of abating.

What is the reason for India’s sudden popularity? Sharon Himes, a major U.S.-India tour operator, commented that the increase in travel to India reflects “a growing interest in India and its fascinating culture.” Recent media exposure seems to have only further piqued curiosity about a country and life-style so different from our own.

Ken Taylor, who wrote the screenplay for the TV series The Jewel in the Crown, based on Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet, attributes the series’ popularity to the continuing appeal of Indian spiritual culture. “Something in the culture and philosophy of India affects the Western mind,” says Taylor. “I suppose it is the opposite of the Western ethos, which is materialistic and competitive.”

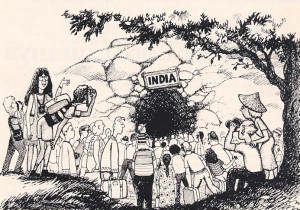

Yet, with India closer than ever by jumbo jet or the flick of a TV dial, are we any closer to understanding the real India than were the British imperialists who booked their long passage to India on the P & O steamers?

The search for the real India is the focus of David Lean’s critically acclaimed film A Passage to India, based on E. M. Forster’s novel. The story concerns one young English lady named Adela Quested, who is newly arrived in British India accompanied by her would-be mother-in-law, Mrs. Moore. Miss Quested wants to see the real India, and that sets into motion the fateful events of the story. For to see the real India she would have to get to know the natives, and in those days that simply wasn’t done. The ruling Britishers, especially the memsahibs (English ladies), were not to cross the social barriers and mix with their subjects. To do so was thought to court certain disaster. The Indian hero of the story, one Dr. Aziz, in his childlike naivete, eagerly desires to please the English ladies, and he arranges for an ill-fated excursion to the Marabar Caves.

In Forster’s Westernized vision of an inscrutable India, a strange, untidy place of curious misadventures, whatever could go wrong often does. And sure enough, the excursion to the Marabar Caves turns out to be a disaster. Confronted by the resounding echoes of the empty, fathomless caves, which reverberate with a kind of eerie cosmic boom or om, the memsahibs lose their mental equilibrium. Suddenly, all their mundane conceptions are shattered, and love, religion, and the affairs of men all at once seem insignificant. What the empty echoing caves represent—an impersonal conception of God, a “void” in the universe, or an existential emptiness—is deliberately left ambiguous. Although Miss Quested believes she was physically molested in the caves, what exactly happened is also left ambiguous.

Accused by the distraught Miss Quested of attempted rape, the hapless Indian doctor becomes entangled in a web of cultural prejudices and misunderstandings. The volatile case is brought to the local English court and a highly emotional trial ensues.

If Miss Quested was not physically molested, as the self-righteous Britishers believe she was, then what did happen to the poor girl that disturbed her so much as to drive her madly out of the caves? As one of the characters suggests, “India forces one to come face to face with oneself; it must be very disturbing.” What must be even more disturbing is to come face to face with oneself and not find out who one actually is. Ignorant of the science of self-realization, neither Forster nor Lean offers us no clues whatsoever.

David Lean’s version is not faithful to Forster’s vision, nor does it offer any personal vision of its own. The only original element introduced by Lean is a bicycle excursion by Miss Quested into the upcountry, foreshadowing the trip to the caves. Heavily loaded with Freudian undertones, the nightmarish sequence shows the repressed Miss Quested riding her bike off the dusty path of Western Christian morality (symbolized by the road signpost in the shape of a cross) and then veering off into a lush, overgrown jungle, where she encounters the ruins of erotic sculptures from a temple swarming with libidinous monkeys. In this way, Lean distorts Hinduism by using it as a symbol for carnality and irrationality, a familiar Hollywood stereotype of “heathenism,” quite different from what Forster had to say.

Forster’s vision of Hinduism is expressed in the novel’s concluding segment, which, unfortunately, Lean saw fit to excise. Forster named this section “Temple,” referring not to an erotic temple but to a Krsna temple at the time of Janmastami, the annual celebration of Lord Krsna’s appearance in this world. Forster saw “Temple” as a necessary complement to his novel’s other two sections: “Mosque” and “Caves.” The third and final part of the novel is about bhakti, the path of understanding the ultimate reality through devotion to the supreme personal Deity, Lord Krsna. This view—which happens to be the sum and substance of Bhagavad-gita—is propounded by the fourth major character of the novel, the enigmatic brahmana, Professor Narayan Godbole.

In the novel, Professor Godbole, as the English translation of his name implies, is always absorbed in singing, chanting, or meditating on his Lord Krsna. As revealed in the book (though not in the movie), Godbole is a devotee of Tukaram, the great Maharastran saint and follower of Srila Caitanya Mahaprabhu. The “Temple” segment climaxes in the ecstatic celebration of Janmastami, after which all the misunderstandings and divergences between the characters are miraculously reconciled. This transcendental ending would have been appropriate for the movie as well. Unfortunately, Lean left out the one essential element for understanding the self and God. By omitting the integral element of bhakti (devotion to Lord Krsna), the filmmaker not only fails to clarify anything but also confounds the muddle by tacking on the stock Hollywood driving off-into-the-sunset ending.

It is clear that you won’t learn a great deal about the real India and its spiritual culture by watching the movies. Nevertheless, if the movie A Passage to India induces sincere seekers to delve into the real spiritual India, then it will have served some useful purpose. To find the real India, as was stated in the movie, one must meet the people. But which people? Certainly not those people seeking fame and fortune in the material world. For this there is no need for the soul to take the proverbial “passage to India.”

Rather, we must search out the genuine sadhus (saintly persons) and spiritual masters to guide us in our search for the truth. This is the prescription of Lord Krsna in the Bhagavad-gita (4.34): “Just try to learn the truth by approaching a spiritual master. Inquire from him submissively and render service unto him. The self-realized souls can impart knowledge unto you because they have seen the truth.” Without the help of self-realized souls who can impart the unchanged knowledge of the Vedic literature, the Vedic culture of India must always remain a puzzle. It baffled the Moghuls; it baffled the British; and now it seems to have baffled the Hollywood moguls as well.

India is the last great repository of the once universal Vedic culture, the spiritual culture that teaches that self-realization and not sense gratification is the goal of human life. It is still practiced in many parts of India, though in various, often adulterated, forms and permutations. The sincere seeker, however, need not despair of being unable to undertake a costly voyage to India. The spiritual culture of India in its pure and unadulterated form is being spread all over the world by the members of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. The transcendental knowledge imparted in Srila Prabhupada’s books is no mere holiday excursion to India, but a lifetime’s liberal education in itself.

Chemical Camouflage

by Mathuresa dasa

The U.S. Army is repainting tens of thousands of pieces of field equipment with a new, three-color camouflage design, replacing the standard, four-color design in use since the mid-seventies. Thousands of construction machines, such as road graders and earth scrapers, have been painted already, at a cost of about $300 per vehicle, and major weapons. such as the M-1 tank and the Bradley armored personnel carrier, are next in line.

The U.S. Army is repainting tens of thousands of pieces of field equipment with a new, three-color camouflage design, replacing the standard, four-color design in use since the mid-seventies. Thousands of construction machines, such as road graders and earth scrapers, have been painted already, at a cost of about $300 per vehicle, and major weapons. such as the M-1 tank and the Bradley armored personnel carrier, are next in line.

Stuart A. Kilpatrick, director of the Army’s Combined Arms Support Laboratory at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, says there are two primary methods of camouflage. The four-color method makes the painted object blend with its background, while the three-color method obscures the shape of an object viewed from more than three hundred yards away.

So what’s the big difference? Considering that radar, heat sensors, night vision devices, and a variety of battlefield conditions can eliminate the subtle advantages of any camouflage design, why spend millions for the changeover?

Well, there are a couple of reasons. First of all, although both the three- and the four-color designs are well suited to the terrain in Central Europe, where the U.S. Army maintains a lot of its equipment, the four-color sometimes has to be changed to match seasonal environments there, whereas the three-color can remain the same year round. But more significantly, the changeover will allow the Army to use a new polyurethane paint known as CARC (Chemical Agent Resistant Coating), which resists chemical warfare agents better than the enamel paint used in the four-color scheme. With CARC, the Army will be prepared for the worst—if the enemy decides to use nerve gas, we can rest easy that the military vehicles’ paint jobs won’t be ruined.

But there is a catch. CARC contains hexamethyl di-isocyanate, a chemical cousin of methyl isocyanate, the deadly gas that leaked from the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, India, last December, killing more than two thousand people and injuring some twenty thousand more. So painters using CARC have to wear respirators and airtight suits, and they must remain under constant medical surveillance. And that’s only the paint. Just imagine the “medical surveillance” that will be necessary if some of the stuff that CARC’s supposed to resist “leaks” into Central Europe.

Union Carbide and the U.S. Army are among the organizations at the forefront of this century’s technological revolution—leaders in the development, testing, and application of the latest hardware produced by the world’s best scientific minds. Their example demonstrates that, on the whole, modern science has contributed more to accelerating death than to prolonging or improving life.

Sure, methyl isocyanate helps us eliminate lots of pesky insects, but even if we write off Bhopal as a freak accident and painter asphyxiation as an occupational hazard, can we honestly believe that the widespread use of lethal chemicals won’t have a detrimental effect on the environment and on our health? According to the British relief agency Oxfam, in 1982 alone pesticides caused 10,000 deaths and 375,000 poisonings in developing nations—enough to make Bhopal appear small-time. And if those statistics don’t convince us that the development of deadly chemicals is more trouble than it’s worth, then we might try guessing how many tons of methyl isocyanate, or of its “cousins,” are now stockpiled in superpower arsenals.

The Vedic literature informs us that human life is meant for spiritual advancement, which is the proven way not only to raise the quality of our lives but to eliminate death altogether. The Bhagavad-gita states that by practicing the spiritual science of bhakti-yoga, many, many people have surpassed death and have attained eternal life. After passing away from their physical bodies, they never took birth again in this world, where death conquers everyone.

Conversely, the Srimad-Bhagavatam warns us that material, or technological, advancement is inevitably accompanied by perils that always counterbalance, and usually outweigh, its advantages. For example, material science has brought us to the point where we can prolong a man’s life for a few months or years by installing a plastic heart, but that can cost millions of dollars per patient, without any guarantee of even temporary success. Material science has also brought us CARC, a gallon or two of which could most likely do in at least a dozen unwary camouflage painters in a matter of hours or minutes—and a gallon of CARC costs only thirty-five bucks.

Occupational Hazards

by Tattva-vit dasa

When I was in college fifteen years ago, my father’s advice that I structure my academic program in terms of a career plan seemed to me to betray the spirit of education, the spirit of understanding myself. “Making a living” and getting “a good job” were middle-class, ephemeral goals that held little attraction for me and thousands like me. But values change, and today’s young people seem much more satisfied with the status quo and with filling the ranks of America’s work force. A New York Times columnist reported on November 25, 1984, “If public opinion polls as well as the strong turnout of young voters to support the more conservative policies of the Reagan Administration are to be believed, there may have never been a time in the history of this country when young people were more preoccupied with the making of money.” Fortunately, even young people interested in making money aren’t disqualified from understanding their true identity if they accept the guidance of a bona fide spiritual master. If they neglect self-realization, however, even though they may gain the whole world, they will lose an opportunity to elevate their immortal souls.

According to the Vedic literature, people traditionally turn to religion for material gain. In many of today’s affluent societies, however, people are realizing their material aims without the help of religion; therefore, religion is being neglected. People are more interested in shopping malls and office buildings than in the churches and temples their forefathers erected.

Materially motivated work, however, is not at all like working for self-realization. The happiness we appear to gain by working hard and spending our money on sense enjoyment ends at death. The end of self-realization, in contrast, is to reawaken our understanding that we are not these bodies but eternal spirit souls, the servants of Krsna, or God, the supreme proprietor. The happiness enjoyed in rendering unto God what is God’s is unending, because it is spiritual bliss.

Ideally, all work should be service to Krsna. For example, in the Hare Krsna movement a devotee may work to convince people that instead of spending their money on sense gratification, they should spend it n books about Krsna or on building ample for Him. Or a devotee may work, without salary, in Krsna’s temple. Devotees who hold regular jobs or who are self-employed, donate a substantial part of their salaries or profits to a temple. And those who can’t be full-time devotees often become life members of the Krsna consciousness movement or donate some part of their earnings. One may be engaged in various activities, but no work should be done without some relationship to Krsna.

Ordinarily, in the struggle for existence, work simply ends in defeat. Work performed for sense enjoyment produces reactions, and any reaction, good or bad, entangles the worker in the web of karma. Thus the soul must accept another body to enjoy and suffer the good and bad reactions to work. This is something like contracting a disease. If a man contacts the smallpox virus, then under certain conditions after seven days he will develop the symptoms of the disease. And karma is just as real as smallpox. Our actions of today will produce reactions—some good, some bad—in the future. Ordinary work, therefore, binds us in the material world.

A devotee, however, rids himself of both good and bad actions (and reactions) by working only in Krsna’s service, and he conquers repeated birth and death. This is the great art of doing work. It is a practical method of self-realization even for young people preoccupied with making money, who spend the largest block of their waking hours at a job, trying to get ahead. It will help them to go back home, back to Godhead.

Leave a Reply