Transcendental Commentary on the Issues of the Day

Youth Suicide:

Encounters With Hopelessness

by Drutakarma dasa

The time is five thousand years ago. The place, the Battlefield of Kuruksetra, in northern India. The warrior Arjuna is undergoing a moment of intense anxiety just as he is about to enter into combat. Overwhelmed with doubt and despair, he says, “I am now unable to stand here any longer. I am forgetting myself, and my mind is reeling. I see only causes of misfortune.”

The time is five thousand years ago. The place, the Battlefield of Kuruksetra, in northern India. The warrior Arjuna is undergoing a moment of intense anxiety just as he is about to enter into combat. Overwhelmed with doubt and despair, he says, “I am now unable to stand here any longer. I am forgetting myself, and my mind is reeling. I see only causes of misfortune.”

Srila Prabhupada explains in his commentary on this passage from the Bhagavad-gita: “When a man sees only frustration in his expectations, he thinks, ‘Why am I here?'” Of course, Arjuna eventually recovered from his moment of self-doubt and went on to victory. But if a person can find no satisfactory answer to the question “Why am I here?” then he might conclude that ending his existence is a practical solution.

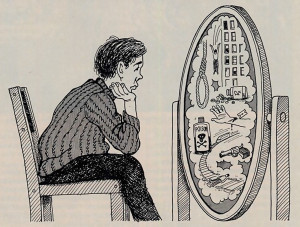

Unfortunately, this is exactly the conclusion that more and more American young people are reaching. Seeing only unhappiness in their futures, they are taking their own lives in numbers that are shocking. Surprisingly, many of the victims are quite well off in terms of material well-being and social status.

Cathy Ann Petruso was a popular seventeen-year-old high school senior in New York’s Westchester County. Captain of the cheerleading squad, she had also been selected by her classmates as homecoming queen. She seemed to have everything going for her; yet one summer night she hung herself with her own belt in the rest room of a drive-in movie theater. Hundreds of similar examples could be cited.

In recent years suicide has ranked second or third as the leading cause of death among people under twenty-four years of age. Each day, an average of eighteen American young people kill themselves, and according to some mental health professionals, the number of unreported suicides could double or triple the total. Furthermore, Dr. J. Vernon Magnusson, a professor of child psychiatry at the Emory University School of Medicine, estimates that the number of suicide attempts is fifty times as great as the number of reported deaths, now running at a rate of almost six thousand a year.

The reasons for the suicide epidemic are a matter of controversy. But in all analyses a predominant theme emerges—in their search for happiness, teenagers are encountering a sense of extreme hopelessness.

Some observers have attributed this to a lack of traditional religious values. Steven Stack, a student at Pennsylvania State University, says, “Religion supplies moral guidelines. . . . Young people, while freer, are also more unhappy.” However, most people are probably already aware of traditional guidelines, but see little reason to follow a list of “don’ts” that seem to do nothing more than deny the human desire for happiness. So, instructing young people in a list of moral guidelines may not be the complete answer.

According to the sages of ancient India, underlying our deep dissatisfaction and frustration is a fundamental lack of knowledge about our own inner nature. We do not understand who we really are.

The problem thus becomes one of identity. The Bhagavad-gita teaches that the real self is the soul. Without the presence of the spirit soul, the body is a lifeless lump of matter. The body is, therefore, simply a temporary vehicle for the soul. By nature, the soul is eternal and full of happiness and knowledge. If one can remain fixed in this knowledge of the self, one experiences complete satisfaction along with freedom from all kinds of fears and anxieties. The reverse is also true. If one is always looking outside the self—to the body and material objects—for pleasure and satisfaction, one is always going to remain frustrated in one’s search for happiness, without knowing why. And it is this sense of not knowing why one is unhappy or what to do about it that is doubtlessly a major contributing factor in the impetus toward suicide. The fear of the future becomes so overwhelming that one can no longer confront it.

The state in which the mind is completely focused upon the actual self within the body is technically called samadhi. The Gita says, “In the stage of perfection called trance, or samadhi, one’s mind is completely restrained from material mental activities by the practice of yoga. This perfection is characterized by one’s ability to see the self by the pure mind and to relish and rejoice in the self. In that joyous state, one is situated in boundless transcendental happiness, realized through transcendental senses. Established thus, one never departs from the truth.”

The methods for attaining this position of self-realization are described in the Gita. The effectiveness of these techniques leads Dr. Elwin H. Powell, a professor of sociology at the State University of New York, to declare, “If the truth is what works . . . there must be a kind of truth in the Bhagavad-gita As It Is, since those who follow its teachings display a joyous serenity usually missing in the bleak and strident lives of contemporary people.”

Of course, the Gita’s teachings are meant for everyone—not just those unfortunate young people who might be contemplating taking their own lives. But here’s something we can all consider: if we don’t become self-realized in this lifetime, then according to the Gita, we will remain entangled in an endless cycle of births and deaths. In effect, if one does not seriously take up the process of self-realization, one is committing a kind of spiritual suicide.

Day Of The Living Dead

by Mathuresa dasa

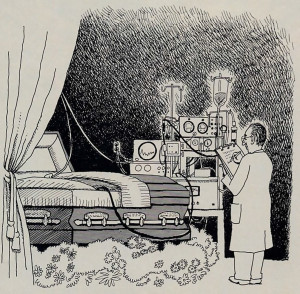

Staying in Intensive Care Units (ICU’s) in U.S. hospitals can cost upwards of $600 a day. Add to that base rate the charges for respirators, kidney dialysis machines, drugs, lab tests, and so on, and a daily bill of $2,000 is not unusual. In 1982 Americans spent about $28 billion—or nearly one per cent of the gross national product—on ICU’s.

Staying in Intensive Care Units (ICU’s) in U.S. hospitals can cost upwards of $600 a day. Add to that base rate the charges for respirators, kidney dialysis machines, drugs, lab tests, and so on, and a daily bill of $2,000 is not unusual. In 1982 Americans spent about $28 billion—or nearly one per cent of the gross national product—on ICU’s.

And why not spend so much? ICU support systems maintain our most valuable possession: life.

Or do they? Critics point out that although the advanced medical technology used in ICU’s can support a patient’s organ system for long periods, it cannot cure the underlying diseases. Put a terminally ill patient in an ICU and he’s still terminally ill. He has no hope of living normally, and even his bed-ridden existence is tenuous. Sometimes patients are “kept alive” under such conditions against their wills, and may even have to be tied down to prevent them. as they thrash about in pain, from pulling the life-sustaining tubes and needles from their bodies. So at least in some cases, ICU’s appear to prolong not life, but the agonies of death.

A devotee of Krsna always remembers that his life and death are in the hands of the Supreme Lord and that an ICU cannot in itself prolong anyone’s life even for a second. A devotee looks after his health and may take whatever steps are necessary—including those of the most advanced medical technology—to keep physically fit. But he never makes the mistake of thinking that his physical well-being can ever be fully controlled by medical technology. Whether the medicine works or not or whether the ICU does in fact keep him alive is ultimately up to Krsna.

Furthermore, a devotee does not take his physical body as all in all. He knows that he is an eternal individual spirit soul situated within a temporary body and that the death of the body does not mark the end of his real self or of his service to Krsna.

Much of the emphasis on the use of ICU’s is a result of the lack of knowledge that we are transcendental to our physical bodies. A society that falsely thinks that the individual dies with the death of the body is bound to spend billions to try to keep the body alive, even if only for a few extra moments—and even if those moments are a living death. On the other hand, one who knows the self is transcendental will be more inclined, when faced with imminent death, to rely fully on Krsna, rather than on an ICU.

Hey, I was wondering if I have permission to use the first picture for my school assignment. It wouldn’t be published and it just would be shared with my teacher.

Yes. Its OK, you can use it.