Transcendental Commentary on the Issues of the Day

1984 Revisited

by Suhotra Swami

Happy New Year! Thirty-six years ago George Orwell selected this year’s date as the title of his novel of ominous social prophecy. In his vision, the nations of the world of 1984 would form three superstates, pitted against one another in constant war. Winston Smith, the main character of 1984, is an official in the government of Oceania, and his duty is to revise recorded history so that it conforms to the political dogma of Big Brother, Oceania’s all-powerful leader. Life is depicted as dreary, dull, joyless. Those who count for anything in society—the employees of the State—live under constant surveillance. A careless remark, a few sentences of despair hastily scribbled in a notebook can cost a citizen his sanity in the dungeons of the dreaded Thought Police. For the masses, those persons who are not members of the Party, the State demands less rigid conformity, if only because the masses have become little more than human robots, whose minds are devoid of the ability to think critically.

Happy New Year! Thirty-six years ago George Orwell selected this year’s date as the title of his novel of ominous social prophecy. In his vision, the nations of the world of 1984 would form three superstates, pitted against one another in constant war. Winston Smith, the main character of 1984, is an official in the government of Oceania, and his duty is to revise recorded history so that it conforms to the political dogma of Big Brother, Oceania’s all-powerful leader. Life is depicted as dreary, dull, joyless. Those who count for anything in society—the employees of the State—live under constant surveillance. A careless remark, a few sentences of despair hastily scribbled in a notebook can cost a citizen his sanity in the dungeons of the dreaded Thought Police. For the masses, those persons who are not members of the Party, the State demands less rigid conformity, if only because the masses have become little more than human robots, whose minds are devoid of the ability to think critically.

While Orwell’s book is perhaps an accurate foretelling of the rise of totalitarian communist empires, another book, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, predicts a world more comparable to a modern Western technocracy.

God, for Brave New World, is science and technology, which extends its influence to all corners of life. Babies are mass-produced in test-tubes, and the children are raised in a tightly controlled but seductively benign environment. All state citizens are trained to fill slots in the complex social machinery, and any tendency in a child to rebel is met by systematic psychological manipulation. The “happiness” of the residents of the brave new world revolves around free sex (marriage has been abolished) and drugs (soma for depression, feelies for enhancing excitement). Persons unable to conform to the brave new world are considered savages. They are banished to reservations where they are granted “the right to be unhappy.”

The stark prophecies of 1984 and Brave New World do not perfectly describe contemporary society, but noteworthy similarities are there, nonetheless. In London, for instance, there is a reservation of sorts in King’s Row, where thousands of self-proclaimed savages have taken up a life-style characterized as “the new tribalism,” with tribal names like “the Punks,” “the Skinheads,” “the Rockabillies,” and so on. Similar tribes roam the streets of Paris, Berlin, New York, and San Francisco. Bedecked in their bizarre costumes, they idly gaze into an empty future, while society around them becomes more and more complex and depersonalized.

But perhaps for most of us, a blind optimist within smiles, “I’m looking forward to a happy 1984. I’ve got my own life to live. I can make my own choices. If I want to go to school, I can do that. If I want to get a job, I can do that, too. I can get stoned on cocaine. Or if I want to drop out—well, that’s also my right. I’m free!”

Yet who among us can say that we have independently arrived at our personal definition of happiness? Happiness is defined for us by parents, friends, teachers, politicians, psychologists, scientists, and so on. A laboratory rat is free, too. He runs down an alleyway, turns left, then right, and has a choice of levers to push: one for food, one for drink, one for sex. But the rat may also perish at any moment in the rubber-gloved hands of his big-brother scientist, who gazes down upon his little world from far above.

And far above us, in outer space, surveillance satellites, their unblinking electronic eyes able to read the license plates on our cars, look down upon the maze of our little world. Should they detect things a big brother in Washington or Moscow doesn’t like, a signal might be relayed to a missile crew deep under the earth or to a submarine cruising beneath the sea. And in minutes, our world could burst into atomic flames.

Sure, it’s frightening, perhaps more frightening than Orwell and Huxley imagined. And what’s the solution? These authors—being materialists—didn’t have one. Long before Orwell or Huxley, however, sages of ancient India predicted in their writings the ills that would afflict us in the present age. The Srimad-Bhagavatam, a treasure house of Vedic wisdom compiled five thousand years ago, refers to our time as Kali-yuga, the age of quarrel. The Bhagavatam describes Kali-yuga as an “ocean of faults.” But it also recommends deliverance from this ocean through the chanting of the holy names: Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare.

The chanting of Hare Krsna is, quite simply, liberating. When one chants Hare Krsna, he liberates his consciousness from its physical and mental coverings. He no longer identifies with the mortal designations of male or female, white or black, American or Russian, but he realizes he is an undying soul. By this knowledge he is freed from the cycle of birth and death.

No, Krsna consciousness isn’t pabulum for those too weak to face the world as it is. A Krsna conscious person is the most uncompromising realist and has no false optimism about living in the material world—in 1984 or any other time. Nor does he retreat into listless despair. He knows he is not the body but is an eternal servant of the Supreme Lord. A Krsna conscious person, out of natural compassion, is eager to work enthusiastically in this world to give Krsna consciousness to others, and his only reward is that his service be accepted by Krsna. Such a devotee is always satisfied, even in the most adverse circumstances.

The year 1984 has just begun, and already the prospects are as ominous as the predictions of Orwell and Huxley. A deliberate. or even accidental, push of a button could set the clock back a thousand years. Our cities, our machines, and our science could be consigned to a mass tomb. Then, standing in the lonely shadows of failure, we would be forced to face ourselves at last and to recognize ourselves for what we really are.

Or we could make it easy on ourselves and give up voluntarily the heavy burden of our false lordship by simply accepting the sublime wisdom of the sacred Vedic texts. This wisdom transcends the limitations of space and time, and it is known as Krsna consciousness. It’s as fresh and relevant now as ever. Modern man, whose great intelligence is stranded in a meaningless chaos of his own making, has great need of it.

Who Art In Heaven?

by Drutakarma dasa

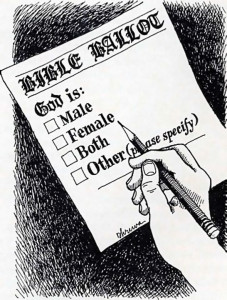

In response to feminist pressure for a “nonsexist” rendering of the Bible, the National Council of Churches has changed the phrase “God our Father” to “God our Father [and Mother].”

In response to feminist pressure for a “nonsexist” rendering of the Bible, the National Council of Churches has changed the phrase “God our Father” to “God our Father [and Mother].”

But is God just a formless spiritual entity to which we can attach whatever labels we currently favor? Who is God? Is God masculine, feminine, both, neither? Does anybody really know?

Traditionally, Christians have favored a conception of God as a grey-bearded old man. But when this view is challenged, as is now happening, there’s little scriptural evidence that can be marshalled in support of the conventional image of God. In other words, the Bible doesn’t really reveal much about what God looks like.

Of course, all the difficulties about the identity of the creator could be very easily resolved if the actual form of God were ever to be revealed to humankind. Amazingly enough, this has already taken place, most recently five thousand years ago, when the Supreme Lord appeared in His original spiritual form in India. Srimad-Bhagavatam, the Sanskrit classic which records the history of the Lord’s incarnation, states, “Dear Lord, if You did not appear in Your eternal transcendental form, full of bliss and knowledge . . . then all people would simply speculate about You according to their respective modes of material nature.” That, of course, is exactly what is happening now.

Srila Prabhupada comments, “The appearance of Krsna is the answer to all imaginative iconography of the Supreme Personality of Godhead.” (Krsna is the chief Sanskrit name of God, who is also known as Allah, Jehovah, and so on.) The form of the Lord, as personally seen by great saints and sages present at that time, is completely described in the Srimad-Bhagavatam and other Vedic scriptures. Lord Krsna appears as an eternally fresh youth, enjoying transcendental pastimes with His associates in the spiritual world, while at the same time, through His remote expansions, He effortlessly creates, maintains, and destroys millions of universes.

He? Before the feminists raise their voices in protest, it should be pointed out that Krsna is not alone. He is eternally accompanied by His feminine counterpart, Radharani. In thousands of temples throughout India (and in ISKCON temples throughout the world). God is worshiped in the form of Radha-Krsna. The Vedic scriptures reveal that Radha is Krsna’s personified pleasure energy.

Srila Prabhupada explains, “It is not that Radharani is separate from Krsna. Radharani is also Krsna, for there is no difference between the energy and the energetic. Without energy, there is no meaning to the energetic, and without the energetic, there is no energy. Similarly, without Radha there is no meaning to Krsna, and without Krsna there is no meaning to Radha. Because of this, the Vaisnava philosophy first of all pays obeisances to and worships the internal pleasure potency of the Lord. Thus the Lord and His potency are always referred to as Radha-Krsna—the potency always comes first.”

Another name for Radharani is Hara. In the vocative case this becomes Hare. So the familiar Hare Krsna chant is an address to Radharani, the personified pleasure potency of Krsna, along with Krsna Himself.

So here’s a suggestion for the more thoughtful feminists—Why go through all the trouble of rewriting the Bible when the Vedic scriptures already contain the perfect explanation of God’s masculine and feminine aspects? And if there’s need of a slogan, the Hare Krsna mantra will serve the purpose more than adequately.

Next-Life Insurance

by Mathuresa dasa

With the economic growth of the twentieth century, insurance sales have blossomed as never before. Americans alone now pay $200 billion a year in premiums—”the gross national premium,” as it is sometimes called. Only the banking industry handles more of America’s wealth. There are 400 million life insurance policies in force in the United States, which means that many Americans have more than one. Altogether, American lives are insured for more than $3.5 trillion.

From one point of view, insurance is simply a way to distribute misfortune. The idea is simple: Since life is full of potential calamities, we can share the financial loss from such calamities by contributing to a mutual fund from which those of us who actually suffer loss may be indemnified. For example, a group of home owners may agree to pay $200 apiece for $20,000 worth of fire insurance on their homes. The assumption is that, at most, one in every one hundred customers will collect his $20,000, but everyone—as insurance salesmen are fond of saying—will have purchased “peace of mind.”

Since insurance, or loss sharing, is a corollary of trade and property ownership, we can assume that it has existed in one form or another throughout history. The merchants of ancient Rhodes shared the risks of their seagoing ventures, and many centuries ago Chinese merchants insured cargo on boats going down the Yangtze River.

Over the centuries the insurance business has given rise to a rich lore. Tales of arson, murder, suicide, and other crimes are plentiful, and new ones still appear regularly in today’s newspapers. “Insurance,” wrote Alexander C. Campbell, a nineteenth-century author, “has made barratry a trade, arson a business, and murder a fine art. There is hardly a crime … of which it is not the prolific mother.”

But our purpose here is not to disparage the insurance business. Serious insurance-related crimes probably get more attention than their relative infrequency merits. And, without insurance, the industry’s defenders point out, no economy can grow. Also, insurance does afford us a certain amount of financial protection.

Not that the premiums we pay make this world any less miserable. Rather, the insurance industry, like the health-care industry, flourishes only because this world is filled with misery. Financial protection is better than no protection at all, but we shouldn’t be made to believe that we’re getting more than that. Life insurance, for example, does not literally insure our lives; it simply provides for our loved ones after we die. It could, therefore, more aptly and honestly be called “death insurance.”

What strikes a student of the Vedic literature is that although we’re insured against fire, disease, death, flood, drought, and unemployment in this life, we have made precious little provision for the next life. Is the possibility of a life after this one such an unlikely risk?

Spokesmen for any religious persuasion could, of course, make facile statements about “eternal life insurance,” threatening us with dreadful fates if we don’t sign up for their brand of salvation. But the followers of the Vedic literatures are not trying to frighten us into buying a bill of goods, like the insurance salesman who conjures up imminent tragedy to sell his policies. The Vedas explain that we are eternal individual souls situated within these temporary bodies. While the body is subject to any number of dangers—it can be burned, cut, crushed, drowned, and so on—the soul is indestructible. When the body dies, we are transferred either to another body in one of the millions of species of life or to the transcendental world, to live eternally in our fully awakened spiritual identities.

As individual souls, we are indestructible, but does that mean we have nothing to fear? The greatest calamity for a soul with a human body is to plummet into the lower species. So while taking all precautions to care for and insure our temporary bodies and properties, we should not neglect our spiritual well-being.

The Vedas give us a documented, well-reasoned warning to this effect. A human being whose life is devoid of Krsna consciousness develops a mentality like that of an animal: he is primarily interested in defending himself, his family, his nation, and so on, so that he can enjoy eating, sleeping, and sex. Whereas the animal has only his claws and fangs for defense, human beings have sophisticated weapons—and sophisticated insurance policies.

Despite the sophistication, however, the mentality of eat, sleep, mate, be merry, and enjoy life is basically the same as an animal’s. In the next life, therefore, such a soul is matched with a suitable animal body, and he loses the opportunity for the spiritual advancement his human intelligence had afforded him.

The Bhagavad-gita states that even a little advancement on the path of devotional service to Krsna can protect one from this greatest of all dangers. We can hardly imagine the work it takes to earn the money to pay $200 billion in insurance premiums, yet every year, thousands of faithful souls, driven by the fear of fire, disease, death, and other catastrophes, manage to pay such a sum. Even a fraction of that labor and money directed towards the service of the Supreme Personality of Godhead, Krsna, could save us from a far greater catastrophe.

Leave a Reply