The Natural Spirit

A former “noble savage” finds

the perfection of natural living—as Krsna’s dairyman.

by Suresvara dasa

Dairyman Sri Krsna dasa is worried. It’s been more than an hour since Cintamani, our oldest cow, seemed to “break water.” Still no calf.

Normally, forty-five minutes to an hour before a cow gives birth, the calf’s fetal membranes burst and a lubricating liquid starts to flow out the birth canal. If the canal dries up before the calf emerges, a veterinarian has to come and pull the calf out raw. This really rips up a cow’s insides, and would probably kill old Cintamani—and her calf.

Sri Krsna paces hear Cintamani’s box stall and chants Hare Krsna. Cintamani’s back end is wide open. Peering inside, he sees what looks like a blood-purple balloon. He puts on a disposable plastic sleeve and reaches in. Pop! Water bursts and two hooves appear.

“Haribol!” Sri Krsna cheers. Real “break water.” The other fluid, excessive mucus, had fooled him. But his relief again turns to dismay when he takes another look at the hooves. “They’re upside down.”

When a calf is upside down, its head gets stuck, and it can’t get out. Nor at this point can old Cintamani push much from the inside. So Sri Krsna ties bailing twine around the calf’s hooves. He pulls hard, but the calf won’t come out. In cases like this, Sri Krsna recalls, the vet reaches way in and flips the calf right-side up. It’s worth a try. He reaches in past the legs—then something brushes his arm. The tail.

“Oh,” he breathes, “it’s just backwards. Right side up and backwards.” Relieved, Sri Krsna gives the hind legs a mighty yank, and out comes the calf.

It’s a heifer!

But since she came out backwards, part of the baggy afterbirth is smothering and choking her. Quickly, Sri Krsna rips away the placental slop and reaches down her throat. After much blowing, he finally gets the stuff out of her lungs, and she starts to breathe. Had Sri Krsna not been there to help, she would have suffocated.

Cintamani, meanwhile, is exhausted. A cow—especially an old cow—cannot carry and deliver her precious calf unaided. She depends upon the care and management given her by the dairyman. And what dairyman cares for her better than a devotee of Krsna, the friend of the cows.

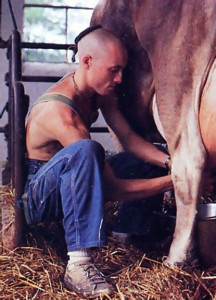

At last, Cintamani looks over and sees her calf. Mooing and grunting, she leaps up to lick and nudge the little one, who starts to nibble on Cintamani’s fleshy brisket. Sri Krsna grins and gets a bucket. As he milks Cintamani, the calf stands and falls. Cintamani is batting her around and mooing up a storm. Sri Krsna gets a bottle and tries to feed the calf, but all she wants to do is stand up. After repeated rebuffs, he decides to break for lunch and try feeding her afterward. He applies an antiseptic to the calf’s navel, then leaves the barn for the temple.

Sri Krsna looks as if he’s been protecting cows all his life. Like many a red-blooded American, though, he grew up hunting animals and eating “beef.” Just before he became Krsna’s devotee, he even took part in killing a cow.

“Mom,” he remembers saying, “I just want to be an animal.”

“But Chris,” his mother replied, “you can’t be an animal. You’re a human being. You have a higher intelligence.”

And yet without Krsna consciousness, Chris’s intelligence was dissatisfied. While growing up in his parents’ ninety-thousand-dollar home in Vermont, he watched them pay dearly for all the modern wonders that were supposed to bring them the good life. “My mother was always crying,” Sri Krsna recalls, “because we couldn’t pay all the bills. And my father was always upset because ‘the good things in life’ were always breaking down.”

Out of high school and determined to live a simple, natural life, the young man and his best friend, Jim, got a summer cabin in the woods.

“We paid the rent with money we’d made working for a landscaper. We looked up to the old lumberjacks in Belmont, who used to chop wood all day and live in tarpaper shacks. We started smoking pipes, rolling our own cigarettes, and wearing weird hats like the old-timers.

“Jim’s sister, Judy, had introduced us to health foods, so we weren’t eating meat. We were cooking seven-grain cereal and eating peanut butter and whole wheat bread. Better than Campbell’s soup, but a long way from krsna-prasadam [food offered to Krsna]. One time a guy came by with pepperoni, and I had some.”

When summer turned to fall; Chris and Jim moved a few miles west into the Green Mountains to build their own log cabin. Using only axes, they chopped down some tamaracks, cut off the limbs, made notches, and stacked the logs up. Very simple. No saws used, not even a nail. “You could see right through the walls.”

Although the growing season was over and Chris and Jim hadn’t stored any food, they were determined to be self-sufficient. They would have to hunt.

“The forest was full of bears, bobcats, wolves, and deer. We were young and strong and crazy as anything. We didn’t know about our higher, spiritual nature, so we thought ‘natural’ meant to be like an animal.”

Shunning firearms, they mostly went after small game. Fisheye lures worked well under the ice; sharp stones found their mark on birds and rodents; wire loops snared as many as a dozen rabbits.

“There were rabbit trails everywhere in the evergreens. We’d tie a wire loop to a branch and drop it over the rabbit’s path. When his head went through the loop, he’d run forward in fear, the slipknot would tighten, and he’d strangle himself.”

As winter set in the cabin became more remote. A hard crust covered five feet of snow; travel was by snowshoes only. Then one night it snowed three more feet.

“We couldn’t even open the door. Finally, we pushed back the drift a little, jumped outside, and disappeared into eight feet of powder.

“We had an Irish setter with us then, too, named Doolittle. We were having a hard time in the snow that morning, but Doolittle was catching rabbits and squirrels like anything. When we got back to the cabin. Jim turned him upside down and played like he was going to skin him. He wouldn’t do that, of course. Doolittle was like our brother. So were all the animals, for that matter, though we hadn’t thought of that. We liked the dog because he was better than us at living natural.”

Catching their own meat may have been more honest than buying it from the butcher, but it was also much harder. And the subzero weather made the skinning and cleaning downright hellish. Another problem: as Judy’s health-food book informed them, their staple—rabbit meat—contained only seven of the eight essential amino acids. But it was another book of Judy’s that really started them thinking. About karma.

“It was a yoga book. It said that the body is a house, the self within is the owner, and there is karma, or reaction, for whatever you do. Do something good, you get good karma. Do something bad, you get bad karma. The book recommended a vegetarian diet, because meat-eating is unhealthy and needlessly cruel. Anything needlessly cruel—like killing animals—is unnatural and therefore bad karma.”

So much for the noble savage. Chris and Jim realized that far from living naturally, they had been transgressing the laws of nature, a nature which had given them a human intelligence with a higher responsibility. But now, exactly what was that responsibility? What was the self within? And nature without? And what, really, was the natural way to live? They had more questions than a little yoga book could answer, but they were on the right track. To start with, they gave up meat for good.

Back in Belmont for supplies, the two of them stocked up on wheat flour, sunflower seeds, and raw peanuts. Also, Chris swapped his marijuana for a warm woolen shirt. By giving up whatever was unnecessary, they figured they could avoid bad karma. They combined bread, peanuts, and seeds with apples they’d sliced and dried in the fall, and that was pretty much their diet the rest of the winter.

But man does not live by bread alone—even if it’s whole wheat. A few times they came down from the forest, sneaked into Jim’s parents’ house, and raided the cookie jar. “We knew we were backsliding when we ate an Oreo.”

Back at the cabin, they started to question the necessity of their cast-iron stove. Maybe even the cabin itself was extravagant. After all, there was plenty of softwood in the evergreens. They could make a brush hut and live inside with a simple campfire. It wasn’t long before they started thinking about going south.

“We could see it was going to be really hard if we stayed in Vermont. So rocky and hilly there. The growing season was short, too. And then winter came and you’d have eight feet of snow all the time.

“We started looking at National Geographic spreads on South America; especially around the equator. We wanted to gather the lushest fruit. Not even pick it, just get it when it fell—that idea again of avoiding karma. And we wanted to find a spiritual guide.”

Before they left, however, destiny entangled them in another hard detail. They needed new boots for the trip, but they wanted to make their own. How to get leather? They heard about a farmer who was going to kill a cow that week. When they approached him, he said if they skinned her, they could keep the hide. He just wanted the meat. They’d heard about the horrendous karma for killing a cow, and they cringed at the thought. But then the farmer was going to kill her whether they came or not. Why not use the hide? They were safe, they figured, as long as they didn’t pull the trigger.

“Slaughtering pigs had been part of growing up and proving you were tough (‘Stick that squealer, sissy!’), but a cow was a lot bigger. We had to take her out of her stall and go down a different aisle. She didn’t want to do that, and right from the start there was fear and slipping, as we pushed her toward the barn door. The big farmer was twisting her tail, pushing and beating on her to go outside. When we got her in the road, he shot her, but he didn’t hit her right. So it was really horrible. She was running around with a shot in her head, bellowing and terrified and no wits. Finally he got her again, and she went down. Just being there, we felt guilty.”

They were. The Vedic literature condemns everyone directly and indirectly connected with animal slaughter: “One who orders, one who kills, one who cuts the dead animals into pieces, one who sells, one who buys, one who cooks, one who serves, and one who eats—all are equally criminals.” And the karmic reaction: “Cow killers are condemned to rot in hellish life for as many thousands of years as there are hairs on the body of the cow.”

Makes “an eye for an eye” sound soft—but there’s good reason. Among the animals the cow is like our mother. Her milk (especially when farm-fresh, hot, and offered to Krsna) empowers our intelligence to understand spiritual knowledge so that we can transcend mortal karma and return home to Godhead. How do cows turn common grass into this miraculous milk? Such is the magic and kindness of Lord Krsna, the cows’ creator and protector. And to deter us from killing His beloved cows, and our own chances for eternal bliss, what warning could be too severe?

It was April and still snowing. The Appalachian Trail ran just a mile from their cabin. Chris and Jim were ready.

“A lady yogi in Belmont had taught us pranayama, breath control. She said that if we ever cut our hair, we’d lose all our spiritual power. Real cuckoo. But anyway, the yoga kept our bowels open.”

Their evolution had turned them toward the East. The day they left the cabin, though, they looked less like Siddhartha than like Huck Finn.

“We wore big wool-felt hats and tied our long hair like scarves around our necks. Heavy blankets covered the fifty-pound homemade packs strapped to our backs. The shirts and pants we’d hand-sewn from unbleached cotton. We stepped into those cowhide boots, picked up our craggy sticks, and took off.”

By foot, the equator was some five thousand miles away. The climate would change as they traveled, but walking would be slow enough to let them adapt. And if they couldn’t eat what the woods provided, they had bought enough peanuts and seeds to last for several months.

South of the Green Mountains, the snow turned to rain.

“It was cold, and our only rain gear was those wide-brimmed felt hats. Our tent was three pieces of canvas, which meant that every night we had to find some sapling, cut it, and stretch out the canvas. No ground cloth, just mud.”

The rain followed them all the way to Pennsylvania. After three weeks, the sun finally broke through. Clear skies prevailed over the hilltop trail, giving Chris and Jim a grandstand view of the countryside. But there was a new challenge: rocks.

“The Pennsylvania mountains were all rocks, so many rocks you just couldn’t avoid them. Millions of rocks. And we felt them right through our rawhide boots. We’d tanned the leather American Indian style—with the cow’s brains—but the boots were hardly giving us any protection. Our feet were aching and started to blister.”

Bad-karma boots. Luckily, Chris had sewn some good karma into his pack: a cashier’s check. Needing relief, they came down from the trail and into a small town to buy sneakers.

“There were two factories in this town, and most of the people there worked in those factories. The fumes from the smokestacks were so bad that all the trees and everything on the mountainside was dead.”

Jim put on his turban (“to catch the prana coming in”), while Chris went into a bank. Everybody was afraid of them. They looked like billy goats and smelled worse. After buying sneakers and food, they looked for a place to rest.

“The church bells were ringing that day, the whole day, and as it got darker, we just followed the sound of the bells right to the church. We slept there, got up, and left.”

More rain for a week. Above Allentown, where the trail crossed the highway, a sign pointed to a nearby hostel. The scowling manager put them up with four young beer-drinkers.

“You guys Jesus freaks?” they asked.

“We’re higher,” said Chris. “Pranayama. “

They had to face it, though, their spirits were sinking. The cold rain, their sore feet—they just couldn’t adapt like the animals. They were human; they wanted to brush their teeth. But what an inhuman world. Even if they made it to some equatorial Eden, supersonic planes would still come to shatter the peace and smite the blue. The planet was too far gone; madmen had long since ruined their garden primeval; and wherever they went, there they were—chased, like everyone else, by the actions and reactions of destiny.

They had the address of a yoga asrama near Harrisburg. Breaking their vow never to ride again in a motor vehicle, they hitchhiked to the city’s outskirts, found the asrama, and parked their walking sticks by the front door.

“We were looking for spiritual guidance, but the people there were scared to death of us. One guy’s wife was sick, and he thought just our presence would kill her—our bad auras. They drove us to their natural-foods store, loaded us up with fruit and vitamins, and dropped us off at a deserted motel.”

Chris and Jim had one last resource. Just before they had left Vermont, Judy had given them a copy of Back to Godhead (Judy’s best friend had become a Krsna devotee). And now, scanning the list of Hare Krsna centers in the magazine, they spotted the address of a Hare Krsna farm in Port Royal. Pennsylvania. Their map showed it was only fifty miles away. They called the farm.

“All of a sudden we were talking with the Hare Krsna people, and although they didn’t know us, they were ready to drive an hour to pick us up. A real friendly exchange. We were proud, though. We told them we’d hitch in.”

Chris called his father and asked him to ship more of the peanuts and seeds they’d stored to Port Royal. The Krsna farm, they figured, would be a rest stop where they would recover their strength and get spiritual stamina for their ongoing march to Paradise.

It was May now. The cows were out to pasture when Chris and Jim arrived—beautiful Brown Swiss, chewing alfalfa, turning it to milk. Two devotees were plowing a field with oxen, a dozen more cultivated a garden nearby. Some children ran out to greet them. Chris and Jim collapsed on the grass, but krsna-prasadam and the devotees’ kindness soon revived them. How happy these people looked.

“The next day we helped Isvari-pati clean out the woods by the temple. We were hauling a dump wagon through tree stumps and underbrush. We wanted to show the devotees we could work really hard, so that they would appreciate us—but we couldn’t keep up with Isvari. We got tired real quick, but he just kept on going. He wasn’t trying to show us up; he was just happy doing his service.”

Devotional service to Krsna, they soon learned, was the natural happiness of the soul. No wonder they had been frustrated trying to live like animals. Human life was intended for realizing they weren’t animals.

“The self is beyond the gross body and subtle mind,” writes Srila Prabhupada, the Hare Krsna movement’s founder and spiritual master. “The body and mind are but superfluous outer coverings of the spirit soul. The need of the spirit soul,” Prabhupada continues, “is that he wants to get out of the limited sphere of material bondage and fulfill his desire for complete freedom. He wants to get out of the covered walls of the greater universe. He wants to see the free light and the spirit. That complete freedom is achieved when he meets the complete spirit, the Personality of Godhead.”

By reading Srila Prabhupada’s translations and commentaries on the Vedic scriptures, by living with the devotees, and by chanting Hare Krsna, Chris and Jim were coming to realize that really Krsna consciousness was the natural life of the soul. But what about their earlier karma? Wasn’t there still hell to pay for all their past activities? They consulted the Bhagavad-gita: “Abandon all paths and just surrender unto Me,” was Lord Krsna’s climactic instruction. “I shall deliver you from all sinful reactions. Do not fear.” The way was clear.

But was their consciousness? The moment of truth came one day when a package arrived from Vermont.

“I was having a hard time,” Sri Krsna recalls. “We were working long hours in the garden, and I was thinking I couldn’t take much more of this. The plan had been to leave as soon as we got more peanuts and seeds, so when the package arrived, I took Jim aside and said, ‘Let’s go.'”

Jim was surprised: “What do you mean, Chris? This is it. Don’t you see? This is the natural spiritual life we’ve been looking for. If we don’t become Krsna conscious, everything is going to be mundane and artificial—even the tropics. Let’s stay, Chris. This is the Absolute Truth.”

“I hated what he was saying,” Sri Krsna chuckles, “because he was right, and that meant I had to stop just serving my body and start serving God. But I had to be honest. Serving Krsna was the most natural thing to do—so we stayed.”

That was in the spring of 1978. By the summer, Chris and Jim were taking care of the cows, and the following spring they became formally initiated devotees.

* * *

Lunch over, Sri Krsna returns to the barn and sees Cintamani lying down with her calf. He scoops Cintamani some grain and feeds the milk bottle to the calf.

“You’ve got to be very Krsna conscious around cows,” he says. “The more you care for them, the more milk they give you. Krsna Himself protects cows, works bulls—what could be more natural than living like Him?”

Gunshots sound unnaturally in the distance. Farmers say they can’t “make it” without killing their old cows. But inside Krsna’s barn, old cow, calf, and dairyman are doing just fine.

Leave a Reply