Cintamani

The Jewel of a Prize Herd

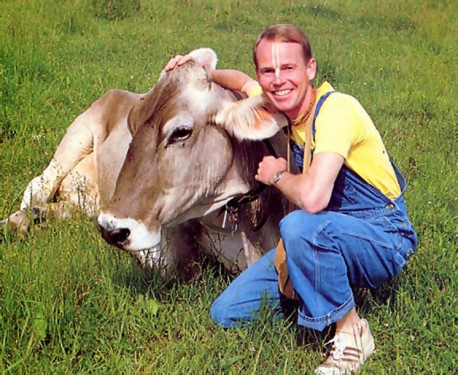

On a farm in Pennsylvania, a hardworking Brown Swiss serves as the emblem of an “honest cow”—and of a dedicated mother.

by Suresvara dasa

Earlier this year, when the Pennsylvania Dairymen’s Association honored the Hare Krsna farm in Port Royal for having the best herd of Brown Swiss cows in the state, what struck us at the PDA’s awards banquet was that all the applause went to the folks with two legs. To top it off, the State Dairy Princess was a high-school cheerleader.

So, to give credit where it’s due, we present the all-state herd’s queen—Cintamani the Cow.

Cintamani (“Spiritual Gem”) is what farmers call “an honest cow.” In other words, she puts all her energy into making milk. Since Lord Krsna’s devotees began taking care of her in 1975, each year she’s given them upwards of twenty thousand pounds of milk. That’s a lot of milk. And a lot of work, when you consider that for each pound of milk a cow pumps practically a ton of blood. Cintamani is so serious about her life’s work that she doesn’t spend a bit of her energy playing with the other cows. And with her high-bridged “Roman” nose, she shows her disdain for doting petters. She just eats, chews her cud, and makes milk.

Cintamani’s bearing is graceful, her disposition always peaceful—even at feeding time. When the devotees break out the corn silage, the other cows usually become a little excited about getting their share of the feast. But Cintamani sits quietly, waits until everyone else is done, and at last gets up slowly to eat. She consumes more than any other cow in the herd, but she never gets fat, because she turns it all into milk. An old brown coat and a bony body dress her dedication, giving her a look of austere elegance.

At fifteen years, Cintamani is the herd’s oldest. But she doesn’t have to worry about some day “outliving her usefulness” and being slaughtered. She remains contented—and productive—because she knows the devotees will protect her always, even after she stops giving milk.

“We are giving proper protection to the cows,” writes His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, “and receiving more than enough milk. At other farms the cows do not deliver as much milk as at our farms. Because our cows know very well that we are not going to kill them,” he explains, “they are happy, and they give ample milk.”

Generally, as soon as a cow’s milk output starts to slip, modern dairymen sell her for slaughter. Ignorant of the Supreme Lord’s instruction in the Bhagavad-gita (18.44) to protect the cow, they take their “dominion over the cattle” (Genesis 1.26) as a license to kill. When they look the cow in the eye, somehow they don’t see a sentient soul like themselves; they see a dollar sign. And the less said the better about people who breed cows strictly for slaughter.

At a Pennsylvania state fair last fall, one big advertisement above some cow pens showed a number of Charolais grazing on lush Texas grasslands. The ad gave quotes telling why these robust, wheat- to cream-colored cows were a good buy.

Producer: “Fast, efficient growth—profitable for me to raise.”

Processor: “Ideal in weight, finish, cutability, quality—efficient for me to process.”

Consumer: “Young, lean, tender, juicy, flavorful—economical for me to buy.”

Below the ad, in the pens, were some real live Charolais. And people were leaning over the fencing and petting them. When I began taking notes, a plump man from York looked over my shoulder.

“Do you know why that cow is crying?” I said, pointing to a cow licking her calf. The man shook his head. “She knows she and her calf are going to be slaughtered.”

“No. . . . Really? I never knew that.” The man had a kind face and, apparently, a simple heart, so I went on.

“She knows the people who keep her don’t really care about her. And those people petting her—you think they care about her kind? What do you think they’ll eat tonight for dinner? If you don’t mind my asking, sir, do you eat meat?”

The man confided that ever since he saw his wife cut off the head of a live chicken, he feels funny whenever he eats meat. “But let me ask you one thing,” he said. “When the cow gets old, what do you do with her?”

“When your mother gets old, what do you do with her?”

“Take care of her.”

“There you go. At our farm, we have about a hundred Brown Swiss. They give us tons of rich milk, and we appreciate it. And so when a cow gets old, we don’t turn around and sell her for slaughter. We protect her.”

Really, when you think about it, cow protection is mother protection. Although as babies we get some milk from our “birth mother,” for most of our life we get our milk from another mother. Mother Cow. She gives us milk, and milk—the miracle food—gives us cream, yogurt, cheese, and butter. Butter, especially when clarified, is the perfect cooking medium. But most of us are so ungrateful that we cook Mother Cow. How can we do this? How can we kill and eat our own mother?

The realization that the cow is our mother moved W. D. Hoard (who a century ago founded America’s leading dairy publication. Hoard’s Dairyman) to post a notice in his barn:

Remember that this is the Home of Mothers. Treat each cow as a mother should be treated. The giving of milk is a function of motherhood; rough treatment lessens the flow.

And lessens the money. What happened to Mr. Hoard’s cows when they passed their prime you can perhaps only imagine, unless, that is, you’ve been to a slaughterhouse. For all his fine sentiments, very likely he also bowed to the sacred cow of “profitability.” But would he or the rest of us ever sell a cow for slaughter, or eat her, if we had to be the one to cut her throat? Or if we knew that by nature’s law, in a future life we cow-eaters will ourselves have to walk on four trembling legs into some slaughterhouse?

Modern dairymen can’t understand why Lord Krsna’s devotees keep a cow when she’s no longer “profitable.” And yet they see that while the devotees’ “old-fashioned method” is bringing prosperity, their own dairy industry is in big trouble. They’re neglecting their cows—and Providence is neglecting them. They’re neglecting life’s real profit—love for God, which starts with following His laws, like “Thou shalt not kill.”

The devotees of Lord Krsna also know Him as Gopala, the friend of the cows. The Lord has created a wonderful cow like Cintamani so that we can draw our nourishment—not by spilling her blood, but by drinking her milk. Her milk fills us with goodness, and as we give protection to her, Lord Krsna smiles and blesses us with peace, prosperity, and love for Him.

Leave a Reply