Krsna’s devotees know the smart

way to treat not-so-dumb animals.

by Suresvara dasa

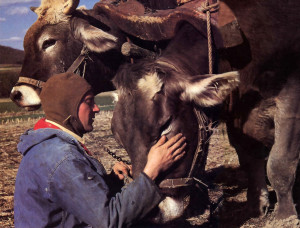

He stands five feet high, eight feet long, and weighs three hundred pounds more than a ton. His name is Bharata, after a pure devotee of Lord Krsna, but because a simple ox responds best to commands of one syllable, the men rhyme his name with spot—“Brot!”

He stands five feet high, eight feet long, and weighs three hundred pounds more than a ton. His name is Bharata, after a pure devotee of Lord Krsna, but because a simple ox responds best to commands of one syllable, the men rhyme his name with spot—“Brot!”

Brot is the leading ox at Gita-nagari, the Hare Krsna farm community in central Pennsylvania.

Inside Gita-nagari’s barn, a driver yokes Brot and five other oxen for spring plowing. Brot and Burf (short for burfi, a favorite milk sweet of Lord Krsna’s) will be the lead oxen in a three-team train, called a span. The oxen love to work—especially Brot. If Brot has a good driver, he’ll pull all day.

The driver walks the oxen out to the fields. A dawn mist shrouds the lowland along the creek. They are going to plow under a four-year stand of grass and alfalfa to prepare the land for corn.

The commands are simple enough—Gee! (Right!), Haw! (Left!), Get up! (Forward!), Whoa! (Stop!)—but they work only if the ox is surrendered to his driver. An ox may seem a dumb brute, but inside that hide and muscle is a sentient soul who knows pleasure and pain, contentment and anger. So an ox must know what is expected of him. He needs encouragement as well as discipline. And Lord Krsna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead, has placed him here not to become our food, but to labor for us, as a father works for his family. Like us, each ox is an individual. One ox may be stronger than another, or smarter, or more high-strung. A good driver considers these things, and his commands are strong and clear.

The driver is Vaisnava dasa. A former agronomy major at Penn State, Vaisnava came to live at Gita-nagari in 1980. “While studying in school and working at a commercial dairy,” he recalls, “I could see how big business was ruining the land and abusing the cow and bull. On most farms a bull won’t live past two—the marketing age for steer beef. But at Gita-nagari a bull will grow up to breed cows or work as an ox.”

Vaisnava carries a lash and occasionally punctuates his commands with a swat on the rump. “Get up!”

Burf and the far oxen walk in the furrow. Brot and the near oxen walk next to them, closer to Vaisnava, who stays back by the last team to keep an eye on the double-bottom plow. Is the guide wheel staying in the furrow? Are the blades turning over the earth at an even depth and width? The oxen pull, the plow cuts, and a wave of fresh topsoil peels into the furrow.

Vaisnava and his span follow the lay of the land to the edge of the field. It’s time to turn. “Brot! Burf! Haw! Come here!” Brot and Burf turn left and walk along the edge of the grass. The second team follows. When the third team makes the turn, Vaisnava lifts the plow and follows the oxen along the border. “Brot! Burf! Haw! Come Here!”

Brot and Burf must turn the span back into the field at the proper angle or the plow will be off. The yoke slants as Brot leans into the turn a little harder than his partner. “Haw, Burf!” One by one, Burf and the far oxen walk into the new furrow. Vaisnava lowers the plow—right on the mark. “Good boys!”

At midday, Vaisnava refreshes the oxen with food and water and lets them rest. Like athletes, the oxen need proper nutrition and training, and they must have a strong relationship with their driver. “The driver is firm but kind,” says the man in charge at Gita-nagari, Paramananda dasa. “A good driver never abuses his servant, but he is very demanding, and he expects him to perform well.”

By three o’clock, when the sun’s heat begins to let up, Vaisnava hitches the oxen and walks them back to the alfalfa stand. Hour after hour the oxen plow. They breathe heavily, and slaver pours from their mouths. As the afternoon turns to twilight, the air cools, and the oxen feel a little relief. By sunset they have plowed three acres.

Vaisnava and the other drivers could plow more with a tractor, but they know it’s not worth it. “You work hard all through the day,” Vaisnava says, “and at the end you’re tired and you go to sleep; peacefully, you go to sleep. Otherwise, you have a tractor that costs thirty thousand dollars, and you park it more than half the year, and you have to be in anxiety about paying what you still owe. Who needs all this anxiety? You just need to be Krsna conscious. Walk behind the oxen—’Dear Lord, please guide me.'”

Last year Gita-nagari’s drivers walked behind seven teams of oxen to plow sixty acres, mow another forty, spread manure, and haul in wood. The devotees are also harnessing the oxen to produce electricity. Four oxen walk in a circle, turning a driveshaft that activates a pulley. The power generated can pump water, saw wood, or thresh grain. “Oxen,” says Paramananda, “are a renewable resource, not dependent on any outside technology. They don’t need gasoline or spark plugs, and they’re a natural by-product of the cow.”

Like a mother, the cow supplies milk, and like a father the ox tills the ground to produce food. Nowadays, of course, the cow and bull are food themselves, and the billboards would have us believe that Elsie and Elmer like being dressed up in A-1 sauce. But nature strikes back for all the slaughter, the Vedic scriptures say, with incurable disease and war. We can never be happy by killing our mother and father. But how many of us ever get to know a cow or a bull?

“Working oxen is as American as Paul Bunyan and Babe,” Vaisnava says, “but last summer when I took Brot and Burf to the Hare Krsna festival in downtown Washington, most of the people didn’t know what the oxen were, that an ox is a mature gelded bull. Oxen pulled the covered wagons west. Oxen helped clear the land. Yet there we were in the nation’s capital, and the people couldn’t recognize one of their founding fathers—the ox. ‘Are they yaks?’ they asked. ‘Water buffaloes?'”

Not surprising. Today only three percent of Americans farm, and even the organic folks almost always use tractors. And we’re too busy eating calves and steers to know what they would have looked like if given the chance to grow up.

“As soon as the people got to know Brot and Burf,” says Vaisnava, “they loved them—especially the kids. They patted and talked to them like their pets. They wouldn’t kill their pets, and face to face with Brot and Burf they could understand that they shouldn’t kill them.”

Gita-nagari provides the time-honored alternative to the modern slaughterhouse civilization. Whereas most alternative communities begun in the sixties and seventies have gone under, Krsna conscious communities like Gita-nagari are thriving.

But the devotees aren’t surprised. After all, who knows better how to show us how to live than Lord Krsna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead? “While herding the very beautiful bulls,” recounts the Srimad—Bhagavatam, “the Lord, who was the reservoir of all opulence and fortune, used to blow His flute, and thus He enlivened His faithful followers, the cowherd boys.”

Paramananda says, “When you work oxen, you have to live simply, the way Krsna lived. We at Gita-nagari are finding that a simple life, based on protecting cows and working oxen, is the best life. Live simply, love God, and be happy.”

Leave a Reply