The Master and the Memorizer

A student of cooking learns that a cook and

a recipe tester are not the same thing.

by Visakha-devi dasi

Ten years ago when I was learning to cook, I would go into the kitchen each morning after breakfast armed with several recipes written by my teacher, Yamuna-devi dasi, take a deep breath, say some prayers to my spiritual master and Lord Krsna, and begin to test the recipes. As it turned out, the recipes weren’t the only thing tested.

Since I knew little about cooking, I was like a blank slate for Yamuna. I quickly learned from her that turmeric was a bright yellow powder that stained my apron and that mustard seeds were small, round, and black and went everywhere when I spilled them. But other things took more time to learn.

I remember intensely studying the jars of urad and moong dal, trying to tell one from the other—I was too embarrassed to ask Yamuna again which was which. Was cumin brownish-gray and fennel greenish, or was it the other way around? And then there were the measurements. How many teaspoons in a tablespoon, tablespoons in a quarter cup, ounces in a pound? Toward the end of the morning I was so dazed by the mental exertion that I generally forgot if I had salted a dish or not. By twelve o’clock both the dishes and the cook were finished.

We would make a lunch offering to Sri Sri Radha-Vanavihari, the Deities of Radha-Krsna Yamuna was worshiping, and then sit down together for lunch.

In one month I had tested almost two hundred recipes. It was an educational experience. Afterwards, however, a problem arose. When devotees heard that I had been cooking under Yamuna’s supervision, they assumed that I had become a cook; they looked on me as Yamuna’s protegee. My service took me many places, and usually, at whatever temple I visited, the devotees would assume I was an expert Vedic cook.

True, I could now tell urad from moong and cumin from fennel (fennel is greenish), but I was a recipe tester, not a cook. Give me a clear, comprehensive recipe, the ingredients, and the equipment, and I could make a reasonable facsimile of the dish. But with no recipe—watch out!

A cook, on the other hand, can take whatever ingredients and equipment are available and make a tasty, balanced meal. A cook can apply the principles and procedures of a tradition and make innovative dishes that are still in keeping with that tradition. A cook’s art is dynamic, and no matter how much she knows, she’s always keen to learn more. And she applies her expertise in unexpected and pleasing ways.

Yamuna was the master, I was the memorizer. After I left her small cottage in southern Oregon, I was called upon to make breakfast daily for a group of devotees in the Los Angeles temple. Drawing on my arsenal of Yamuna’s recipes, I astonished myself and everyone else with the results: boras, badas, wadas, upma, idlis, dosas, sabjis, puris, parathas. But I also began to lament how much time it took me each day to pick the recipes, gather the ingredients, and prepare and serve the meal.

Then, quite unexpectedly, my husband and I were asked to open a temple in Buttertown, a town in northern Malaysia. My husband was the temple president, and I—you guessed it—was the temple cook. Although I thought I followed Yamuna’s recipes just as she had taught me, the dishes never seemed to turn out quite right. But I tried my best, offered the result before our small altar, and had the pleasure of distributing krsna-prasadam to people who had never before tasted it. They appreciated it. We talked to many people about Krsna consciousness and gave them Srila Prabhupada’s books. Before long, sixty guests were attending our Sunday feast. In time we left the temple in the hands of competent Malaysian devotees and returned to our service in the United States.

It has been ten years since I’ve tested a recipe, and the challenge and excitement of those first days, when I was like a budding scientist performing important experiments in a laboratory, has faded. But I’m still benefiting from the experience. When my husband or I start feeling hungry, say around noon, I stop what I’m doing and make a full meal, ready by one. And while it cooks, I can usually even find time to do a few other things. At some point during those years, cooking for Krsna changed for me from a mind-boggling, time-consuming endeavor and became more natural—almost as natural as eating.

In my family we take simple, healthy prasadam. Kichari is one of our favorites. We also enjoy varieties of rices, dals, vegetables, salads, and breads. And when we feel we’re eating the same thing all the time, we go across the street to Yamuna’s house, because she practically never makes the same thing twice.

(Recipes from The Hare Krishna Book of Vegetarian Cooking, by Adi-raja dasa)

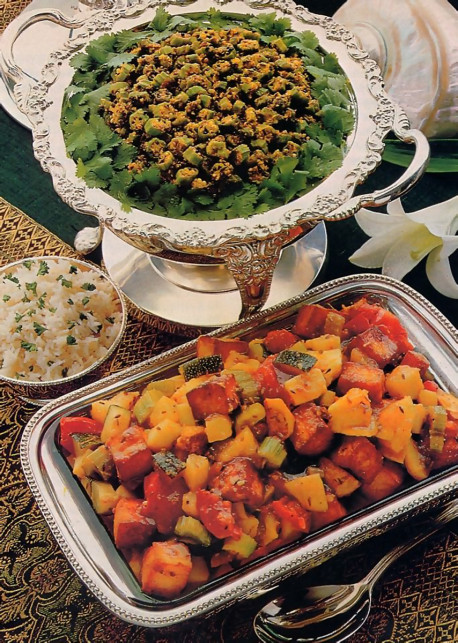

Seasoned Okra Slices with Coconut

(Masala Bhindi Sabji)

Preparation time: 25 minutes

Servings: 4-6

1 pound fresh, tender okra

2 teaspoons ground coriander

½ teaspoon turmeric

1 pinch cayenne pepper

1 teaspoon salt

4 tablespoons ghee (clarified butter) or vegetable oil

1 teaspoon cumin seeds

½ teaspoon black mustard seeds

2 pinches asafetida

2 ounces grated coconut

1 ½ tablespoons lemon juice

1 teaspoon sugar

1. Rinse the okra pods and pat them dry. Cut off the two ends and slice the pods into rounds ¼ inch thick. (You can cut 2 or 3 pods at the same time.) Put the slices in a mixing bowl and sprinkle over them the turmeric, cayenne pepper, salt, and ground coriander. Toss the slices to coat them evenly with the spices.

2. Heat half the ghee in a frying pan; drop in the cumin seeds and black mustard seeds. Cover the pan for a moment to prevent the mustard seeds from popping out. Then toss in the asafetida and fry for a few seconds. Add as many of the seasoned okra as will fit in one layer. You will probably have to fry them in 2 or 3 batches. You should have an idea of how many batches it will take before you start cooking, so that you can divide the ingredients accordingly. Stir-fry each batch of okra for 3 to 4 minutes, until the pods appear to wilt and brown. For each batch, add a portion of the sugar, a portion of the remaining ghee, and a portion of the grated coconut. Keep frying and stirring until the pods turn reddish brown and are very tender. Sprinkle the lemon juice over them and offer to Krsna.

Sweet-and-Sour Vegetables

(Khati mithi sabji)

Preparation time: 40 minutes

Servings: 4-6

6 ounces tamarind

2 tablespoons ghee or vegetable oil

1 teaspoon cumin seeds

2 tablespoons grated fresh ginger

2 green chilies, sliced

½ teaspoon ground black pepper

¼ teaspoon asafetida

1 cup whey

4 ounces brown sugar

1 pineapple, trimmed and cubed

3 carrots, sliced

2 teaspoons mango powder

2 teaspoons paprika

2 teaspoons ground coriander

10 ounces panir (milk curd), pressed and cubed

3 zucchinis, cubed

4 tomatoes, quartered

3 stalks celery, diced

2 teaspoons salt

4 potatoes, peeled, cubed, and deep-fried, or 3 green plantains, sliced

1. Start by making tamarind juice as follows: Tamarind is a bean pod of a tropical tree. The brown pulp is scraped from the pods, dried, and sold in packets. To use, remove the seeds from the pulp and tear or chop the pulp into small pieces. Boil the pieces in a small amount of water for about 10 minutes, or until the pieces of pulp soften and fall apart. (Use about 2 cups of water to 8 ounces of tamarind.) Then force as much of the pulp as possible through a strainer, catching the juice in a bowl. If tamarind is unavailable, you can simulate its flavor by replacing it with a mixture of lemon juice and brown sugar.

2. Then make the masala as follows. Heat the ghee in a large saucepan and fry the cumin seeds, then the grated ginger and green chilies. Next toss in the ground pepper and the asafetida and fry for a few seconds more. Then pour the whey into the masala and simmer for a moment. Add the tamarind juice, brown sugar, pineapple chunks, sliced carrots, mango powder, paprika, and ground coriander. Allow it to boil and thicken, stirring occasionally to prevent scorching.

3. Meanwhile, deep-fry the panir cubes until light brown, and set them aside.

4. Add the zucchini to the masala, cover the pan, and cook until barely tender. Then add the fried panir cubes, tomatoes, celery, and salt. Stir well. If you are using sliced green plantains, add them at this point. If you are using fried potatoes, add them after the panir cubes have soaked up some of the sauce and become juicy. Cover the pan, and cook until all the ingredients are tender. Offer it to Krsna.

Plain White Rice

(Chawal)

Preparation time: Steamed rice: 20 minutes

Boiled rice: 15 minutes

Servings: 4-6

10 ounces basmati or other good-quality long-grain white rice

1 ¾ cups water

1 teaspoon salt

1 or 2 tablespoons ghee or butter

Steamed Rice

This method of cooking rice is the one most often used in India. All the water, and whatever flavoring may be added, is absorbed into the rice. You will need a tight-fitting lid to keep the steam from escaping. If too much escapes, the rice will not cook thoroughly.

If you want to flavor the rice, try adding one of the following: a little lemon juice, a tiny pinch of turmeric, a few raw cumin seeds, the skin (not seeds) of a green chili, or a piece of fresh ginger.

Wash the rice, soak it, and let it drain. Bring the water and salt to a full boil in a 3-quart saucepan.

Heat the ghee in another saucepan over a medium flame and fry the drained rice, stirring for a minute or so to saturate the grains evenly with the ghee. When the grains become translucent, pour the boiling water into the rice. Let the water come to a boil again. Boil rapidly for 1 minute, stirring once to prevent the rice from forming clumps. Cover tightly. Turn the heat to the lowest setting and cook for about 15 to 20 minutes (depending on the type of rice you use), or until the rice has absorbed all the water and is tender and fluffy. Offer it to Krsna.

Boiled Rice

Boiling rice is the quickest way to cook rice. This method is therefore especially useful (but not essential) when the rice is to be mixed with other ingredients. For this method, the rice (washed or unwashed) is boiled in more water than it can absorb; drain when done.

Bring 2 quarts of salted water to a boil in a heavy-bottomed saucepan. Add the rice and boil briskly for about 10 minutes. To tell if the rice has cooked enough, withdraw a grain from the water and squeeze it between your thumb and forefinger. It should mash completely; the center should not be hard. If the center is still hard, boil the rice for a few more minutes and test again. Drain the rice in a colander, then put it into a serving bowl and dot it with butter. Offer it to Krsna.

Tomato Chutney

(Tamatar chatni)

Preparation time: 40-50 minutes

Servings: 4-6

1 ½ pounds tomatoes

4 tablespoons water

1 tablespoon ghee

1 tablespoon fresh ginger

2 or 3 fresh chilies, minced

3 cloves

4 bay leaves

1 cinnamon stick 2 inches long

½ teaspoon cumin seeds

1 pinch asafetida

1 teaspoon salt

3 tablespoons brown sugar

1. Blanch the tomatoes, puree them with 4 tablespoons of water, and set them aside. In a medium-size saucepan, heat the ghee over a medium flame and stir-fry the ginger and the next five spices for 1 minute. Put the tomatoes in the saucepan with the asafetida and salt. Mix with a wooden spoon, cover, and cook over a low flame for 20 to 30 minutes. Stir occasionally at first, then more often as the chutney thickens, until there is hardly any liquid in the pot.

2. Now stir in the sugar and raise the flame. With a quicker motion, stir the chutney for 5 minutes more, or until it has thickened to the consistency of thick tomato sauce. Discard the cloves, bay leaves, and cinnamon stick. Transfer the chutney into a bowl. You can offer it to Krsna as a dip for savories or along with a meal.

Leave a Reply