Back To Godhead Vol 66, June 1974

|

by His Holiness Brahmananda Svami

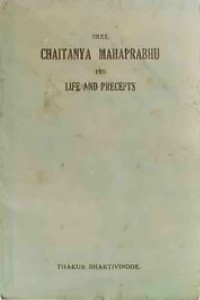

In Calcutta in 1896, the teachings of Lord Caitanya began their journey to the West. In Bengali-speaking Calcutta on August 20th of that year, Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura published a small English treatise entitled Lord Caitanya—His Life and Precepts. Seventyone years later, in 1967, in Montreal, Canada, a graduate student came across a copy of this book while browsing through the rare-book collection of the McGill University library. The book was a wonderful find for him because he was a dedicated follower of Lord Caitanya’s, having been convinced of Lord Caitanya’s teachings by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, whom he had accepted as his spiritual master. Srila Prabhupada was born in Calcutta on September 1, 1896, only a few days after Lord Caitanya-His Life and Precepts was published. Thus by a transcendental arrangement this significant book and he who would fulfill the purpose of the book appeared together.

The sastras (authoritative scriptures) and acaryas (authoritative teachers) affirm that Lord Caitanya, who appeared in Bengal 500 years ago, is the Supreme Personality of Godhead. The great Vedic scripture Srimad-Bhagavatam states that in Kali-yuga (the present Age of Quarrel) the Supreme Lord descends not in His original form as Krishna, but in the garb of a golden-complexioned devotee who constantly sings the name of Krishna. Lord Caitanya, the perfect devotee, descends to teach us how to love Him. Although He is Krishna Himself, He shows us how to love Krishna, like a teacher who takes up a pencil and writes as if learning the ABC’s, just to teach his pupils how to write. Lord Caitanya is Krishna Himself, but as one great acarya has declared, He is more kind then Krishna because He teaches pure love of Krishna

namo maha-vadanyaya

Krishna-prema-pradaya te

Krishnaya Krishna-caitanya-

namne gaura-tvise namah

[Cc. Madhya 19.53]

Thus in this age if one wants to be an unalloyed devotee of God, practically speaking one need only follow the teachings of Lord Caitanya.

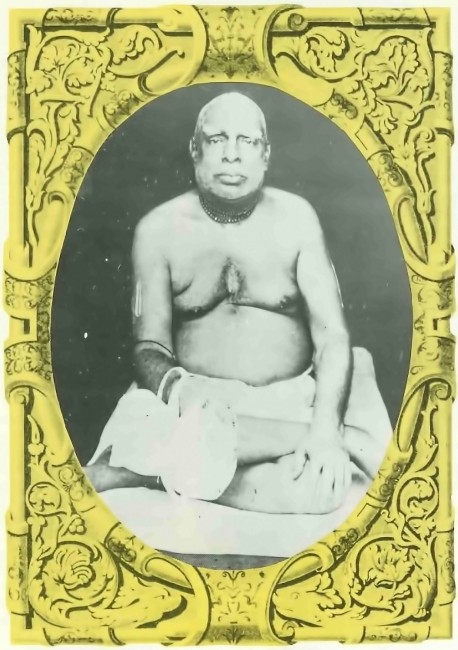

A Trusted Representative The author of Lord Caitanya—His Life and Precepts, Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura, pioneered in bestowing upon the world the benediction of Krishna consciousness through the instructions of Lord Caitanya. He himself appeared near Lord Caitanya’s very birthsite, in the district of Nadia in West Bengal, India, in 1834. Bhaktivinoda Thakura is not a conditioned soul born in this temporary world because of the effects of bad deeds performed in previous lives; he is a nitya-siddha, an eternal associate of the Lord, and he is indeed the transcendental energy of Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu (gaura-sakti-svarupaya). Sometimes during spiritual peril the Lord empowers a trusted representative to act on His behalf, just as a king may send an ambassador to a foreign land to represent him. Bhaktivinoda Thakura is called sac-cid-ananda because he is a representative of the Supreme Personality of Godhead, Krishna, who is also known as sac-cid-ananda-vigraha, the embodiment of eternity, knowledge and bliss. He was sent by Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu to revive Mahaprabhu’s message of Krishna consciousness and thus redeem the modern world.

While cultivating spiritual consciousness, Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura was simultaneously a prominent magistrate in the government of Bengal. Thus Bhaktivinoda’s life exemplifies what he contributed to spiritual knowledge. He proved that renunciation (vairagya) consists not of ceasing or abolishing any activity, but of adjusting every activity and using every object of the world for the service of the Lord, without thought of personal gain or enjoyment. Thus Bhaktivinoda Thakura, while outwardly a materially successful man, was an ascetic of the highest order (yukta-vairagi). He was completely distinct from the stereotyped Hindu ascetics who renounce everything because they think that everything is mundane, yet he was not among the pseudo devotees (sahajiyas) who indulge in sensual pleasure on the plea that because they are part of God they should be free to enjoy like Him.

To live in the Himalayas eating roots and berries, shunning all the activities of the world, actually shows one’s lack of spiritual knowledge. Everything belongs to God. This is the verdict of the Upanisads. Isavasyam idam sarvam yat kinca jagatyam jagat: “Everything in the world, both animate and inanimate, belongs to the Supreme Lord.” Since He is the proprietor, we cannot renounce anything, for one can give up only what one has in the first place. Therefore an enlightened man accepts his quota, what he needs for his maintenance, while at the same time fully aware that God is the proprietor who maintains him.

An Active Preacher

Bhaktivinoda Thakura preached devotional service, which is the real message of the Gita and all the Vedic scriptures. A devotee surrenders everything to Krishna by using everything in the Lord’s service. Srila Bhaktivinoda wrote in one song: “My mind, my household affairs, my body—whatever is mine—I offer to You, my dear Lord, for Your service. Now You can do with them as You like. You are the supreme master of everything, so if You like You may kill me, or if You like You may give me protection. All authority belongs to You. I have nothing to claim as my own.” This illustrates the surrendered attitude of a pure devotee.

For Bhaktivinoda, just to perform devotional service was not enough. As a truly realized soul, he yearned for the day when the entire world would taste the nectar of devotion. Each night the Thakura would rest for only four hours, from eight until midnight, and then he would write until morning, when he would go to the courthouse for his judicial duties. In this way he wrote more than one hundred books while still a magistrate. Bhaktivinoda maintained a respectable position in society, but at the same time explained in detail how to get out of this material world. The result was that people listened to him more respectfully than had he been a hirsute hermit.

Bhaktivinoda wrote his books mostly in Bengali but also in Sanskrit and Urdu, and to make the teachings of Lord Caitanya appreciable to those outside Bengal and India, he also wrote in English. He wrote his first work, Hari-katha, a book of Bengali verses, in 1850. At a meeting in Calcutta in 1869 he delivered a remarkable speech in English entitled “The Bhagavata: Its Philosophy, Its Ethics, and Its Theology.” Other works he wrote in English during this time include “Speech on Gautama,” “Reflections” (poems), “Jagannatha Temple of Puri,” “Slokas on the Samadhi of Thakura Haridasa,” and “Akhadas [Monasteries] of Puri.” Srila Bhaktivinoda started Sri Sajjana-tosani, a unique monthly journal that continued through seventeen volumes. He composed Kalyana-kalpataru, a collection of Bengali songs, and wrote many other books, among them Sri Caitanya-siksamrta, Saranagati, Jaiva-dharma and Prema-pradipa (a fiction showing the excellence of bhakti-yoga). Furthermore, he published numerous Bengali translations of important Sanskrit works, such as Srimad Bhagavad-gita (one edition with Sanskrit commentary by Sri Visvanatha Cakravarti and a second with commentary by Sri Baladeva Vidyabhusana), Sri Siksastaka, Manah-siksa, Sri Visnu-sahasra-nama, Sri Caitanya Upanisad and Sri Isopanisad (with a commentary by Sri Baladeva Vidyabhusana).

A Careful Presentation

During the 1890’s reports came to India of an intensified European and American interest in Indian culture, and a particular interest in Sanskrit. In 1896 Bhaktivinoda penned Sri Gauranga-smarana-mangala-stotra, 104 Sanskrit verses concerning Lord Caitanya’s life and precepts. He sent copies to literary and scholastic luminaries all over the world. Today, Bhaktivinoda’s only surviving son still preserves a letter from Ralph Waldo Emerson, the famous American transcendentalist, gratefully acknowledging receipt of Bhaktivinoda’s book but requesting books in English. As a result of such requests, Bhaktivinoda then wrote Lord Caitanya—His Life and Precepts.

As a preacher, Bhaktivinoda Thakura wanted to make the teachings of Lord Caitanya understandable to people in general and popular among them. This missionary spirit followed the express desire of Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu. Although Lord Caitanya Himself wrote only eight short verses on His teachings, He ordered His chief disciples to write volumes of books explaining, codifying and substantiating these teachings with Vedic authority. It is quite evident from Bhaktivinoda’s books that he took great pains to make these topmost transcendental teachings readily appreciable. For instance, in his speech on Srimad-Bhagavatam, we see the Thakura making an old, massive Sanskrit tome really interesting because he writes about it in such an honest and charming way. He writes: “The Bhagavata has suffered from shallow critics both Indian and foreign. That book has been accursed and denounced by a great number of our young countrymen who have scarcely read its contents and pondered the philosophy on which it is founded. It is owing mostly to their having imbibed an unfounded prejudice against it when they were in school. The Bhagavata, as a matter of course, has been held in derision by those teachers who are generally of an inferior mind and intellect. This prejudice is not easily shaken off when the student grows up unless he candidly studies the book and meditates on the doctrines of Vaisnavism. We are ourselves witnesses to the fact. When we were in college, reading the philosophical works of the West and exchanging thoughts with the thinkers of the day, we contracted a hatred of the Bhagavata. That great work seemed like a repository of ideas scarcely adapted to the Nineteenth Century, and we hated to hear any argument in its favour. To us then a volume of Channing, Parker, Emerson or Newman had more weight than whole lots of Vaisnava works. Greedily we pored over the various commentations upon the Holy Bible and the labours of the Tattva-bodhini Sabha, containing extracts from the Upanisads and the Vedanta, but no work of the Vaisnavas had any favour with us. But when we advanced in age and our religious sentiment received development, we turned Unitarian in our belief and prayed as Jesus prayed in the Garden. Accidentally, we fell upon a work about the Great Caitanya, and on reading it with some attention in order to settle the historical position of that Mighty Genius of Nadia, we had the opportunity to gather His explanations of the Bhagavata, given to the wrangling Vedantists of the Benares school. This accidental study created in us a love for all the works which we could find about our Eastern Saviour. We gathered with difficulties the famous Kurcas written in Sanskrit by the disciples of Caitanya. The explanations we got of the Bhagavata from these sources were of such a charming character that we procured a copy of the Bhagavata complete and studied its texts (difficult, of course, to those who are not trained in philosophical thoughts) with the assistance of the famous commentaries of Sridhara Svami. From such study it is that we have at last gathered the real doctrines of the Vaisnavas. Oh! What trouble it is to get rid of prejudices gathered in unripe years!” It is rare to find such honesty in the field of religion, where blind faith often demands dishonesty in order to keep itself intact.

Next, we see the Thakura writing like a real religious freethinker: “Subjects of philosophy and theology are like the peaks of towering and inaccessible mountains standing in the midst of our planet, inviting attention and investigation. Thinkers and men of deep speculation take their observations through the instruments of reason and consciousness. But they take their stand on different points when they carry on their work. These points are positions chalked out by the circumstances of their social and philosophical life, different as they are in the different parts of the world. Plato looked at the peak of the spiritual question from the West, and Vyasa made the observation from the East; so Confucius did it from further East, and Schlegel, Spinoza, Kant and Goethe from further West. These observations were made at different times and by different means, but the conclusion is all the same inasmuch as the object of observation was one and the same. They all searched after the Great Spirit, the unconditioned Soul of the Universe. They could not but get an insight into it. Their words and expressions are different, but their import is the same. They tried to find the absolute religion, and their labours were crowned with success, for God gives all that He has to His children if they want to have it. It requires a candid, generous, pious and holy heart to feel the beauties of their conclusions. Party spirit—that great enemy of truth—will always baffle the attempt of the enquirer who tries to gather truth from religious works of his own nation, and will make him believe that absolute truth is nowhere except in his old religious book. What better example could be adduced than the fact that the great philosopher of Benares will find no truth in the universal brotherhood of man and the common fatherhood of God? The philosopher, thinking in his own way of thought, can never see the beauty of the Christian father. The way in which Christ thought of His own father was love absolute, and so long as the philosopher will not adopt that way of thinking, he will ever remain deprived of the absolute faith preached by the western Saviour. In a similar manner, the Christian needs adopt the way of thought which the Vedantist pursued, before he can love the conclusions of the philosopher. The critic, therefore, should have a comprehensive, good, generous, candid, impartial and sympathetic soul.”

And finally, we see his humor: “‘What sort of a thing is the Bhagavata?’ asks the European gentleman newly arrived in India. His companion tells him with a serene look that the Bhagavata is a book which his Oriya bearer daily reads in the evening to a number of hearers. It contains a jargon of unintelligible and savage literature for those men who paint their noses with some sort of earth or sandal and wear beads all over their bodies in order to procure salvation for themselves. Another of his companions, who has travelled a little in the interior, would immediately contradict him and say that the Bhagavata is a Sanskrit work claimed by a sect of men, the Gosvamis, who give mantras, like the Popes of Italy, to the common people of Bengal, and pardon their sins on payment of gold enough to defray their social expenses. A third gentleman will repeat a third explanation. A young Bengali chained in English thoughts and ideas, and wholly ignorant of the pre-Mohammedan history of his own country, will add one more explanation by saying that the Bhagavata is a book containing an account of the life of Krishna, who was an ambitious and an immoral man! This is all that he could gather from his grandmother while yet he did not go to school. Thus the Great Bhagavata ever remains unknown to the foreigners, like the elephant of the six blind men who caught hold of the several parts of the body of the beast. But Truth is eternal and is never injured, but for a while, by ignorance.”

The Fight Against Casteism

For his time, Bhaktivinoda Thakura’s approach and thought were downright rebellious. Of all the world’s religions, certainly none is more conventional and reactionary than Indian religion, but there was no protest from the orthodox because Bhaktivinoda presented his arguments most reasonably. This kind of intelligent reasoning, rather than emotionalism, was what Bhaktivinoda used to expose what has been the singlemost perversion of Indian religion: caste consciousness.

Although Gandhi is more popularly known in the struggle against casteism, actually Bhaktivinoda Thakura had campaigned against it long before. And even before him, it was Caitanya Mahaprabhu who first promoted spiritual equality in India. Indeed, Mahaprabhu’s two foremost disciples, Rupa Gosvami and Sanatana Gosvami, had been deemed outcastes by orthodox Hindu society because they had very closely associated with the Muslim rulers of the time. Lord Caitanya also appointed Haridasa Thakura, who was born a Mohammedan, to be the acarya or master of the holy name.

Only one who is enlightened, who sees spiritually, can see all creatures equally (panditah sama-darsinah). One who is materially contaminated must see differences because bodies naturally differ. It is the body which is male or female, brown or white, young or old, American or Indian, and so on. In his Life and Precepts, Bhaktivinoda made Lord Caitanya’s teachings in this regard quite clear:

“The religion preached by Mahaprabhu is universal and not exclusive…. The principle of kirtana, as the future church of the world, invites all classes of men, without distinction of caste or clan, to the highest cultivation of the spirit. This church, it appears, will extend all over the world and take the place of all sectarian churches, which exclude outsiders from the precincts of the mosque, church, or temple.”

Nevertheless, after Caitanya Mahaprabhu, a group of self-interested brahmanas arose who declared that by genealogy they were the only qualified spiritual leaders. Such exclusiveness is very strong in Indian religion and, of course, not unknown in other religions. This group’s idea was to monopolize all religious functions and collect money. Caitanya Mahaprabhu had opposed such imposters. In fact, on one occasion in Benares, as a protest, He purposely resided at the house of a sudra, although it is mandatory for a sannyasi to stay with a brahmana.

Bhagavad-gita describes four orders of spiritual and social life, but nowhere does it hold that one’s birth determines one’s place among these orders. The Gita says: catur-varnyam maya srstam guna-karma-vibhagasah

According to this verse, four classes-intellectuals; administrators, merchants and laborers-are all created by Krishna. Thus we naturally find these different classes in societies all over the world. However, these classes manifest themselves naturally; they are not artificially created. Everyone has different qualities inherent within him and will behave accordingly. But in no circumstances does one’s behavior depend only upon one’s birth. If one’s father is a highcourt judge, this does not mean that one is himself a high-court judge. He also must first be trained and win a judicial appointment. Krishna therefore says that one is classified according to one’s qualities (guna), and not one’s birth (janma). Thus the caste system as created by the Lord is meant to take account of one’s natural qualities, regardless of one’s birth. If one is born in the family of a sudra, or laborer, but has the qualities of a brahmana, or intellectual, then he must be accepted as a brahmana; and if one is born in a brahmana family but has he qualities of a sudra, he must be accepted as a sudra.

History now records how India has generally come to reject caste designations, but Bhaktivinoda Thakura had to fight caste consciousness not only in worldly society but even within religious society. Thus it is rather surprising that anyone who purports to be a follower of Caitanya Mahaprabhu could refuse to accept brahmanas who happen to be born as non-Indians. Lord Caitanya counted

Rupa, Sanatana, and Haridasa Thakura among His chief disciples. He elevated them to the status of Vaisnava, which is even higher than that of brahmana, to demonstrate that anyone who is qualified must be accepted as a sadhu, or holy man. Lord Caitanya even predicted that Krishna’s name would be sung in every town and village of the world. Did He mean that only Indians would be singing Krishna’s name all over the world? Obviously He meant that Europeans, Americans and Africans would also take to the chanting of Krishna’s holy name.

The revealed scriptures state that anyone who takes to the chanting of the holy name is situated on the topmost spiritual platform. Srimad-Bhagavatam says: “If a person born in a family of dog-eaters takes to chanting the holy name of Krishna, it is to be understood that in his previous life he must have executed all kinds of austerities and penances and performed all the Vedic sacrifices.” (Bhag. 3.33.7) Similarly, Caitanya-caritamrta (Adi-lila 7.23) states: “In distributing love of Godhead, Caitanya Mahaprabhu and His associates did not consider who was a fit candidate and who was not, nor where such distribution should or should not take place. They made no conditions. Wherever they got the opportunity, they distributed love of Godhead.” And, again in Adi-lila 7.26: “The Krishna consciousness movement will inundate the entire world and drown everyone, whether one be a gentleman, a rogue, or even lame, invalid or blind.” Lord Caitanya made no bodily distinctions, for His movement is purely spiritual.

The scriptures declare that anyone who discriminates against a qualified devotee is doomed. The Padma Purana states:

arcye visnau sila-dhir gurusu

nara-matir vaisnave jati-buddhih

“One who considers the worshipable Deity of Lord Visnu, or Krishna, to be stone, the spiritual master to be an ordinary human being, or a devotee to belong to a particular caste or creed, is possessed of hellish intelligence.” Nevertheless, such material consciousness still prevails in some religious quarters. Even today the priests of the temple of Lord Jagannatha at Puri will not allow any nonIndian to enter, even though Lord Caitanya Himself stayed there for twelve years and Bhaktivinoda Thakura was the chief administrator of the temple for over five years, from 1871 to 1876.

(to be continued)

His Holiness Brahmananda Svami served for many years as the first president of the first ISKCON temple in the United States (while at the same time working as a teacher in the New York City public school system). He later became director of ISKCON Press and in 1970 accepted the renounced order of life. He was the first to introduce Krishna consciousness in Africa. He has recently been preaching in Africa and India.

Leave a Reply