A sidewalk slip inspires some thoughts

on our schizoid policy toward animals.

by Mathuresa Dasa

Down the street from the house where I live, a tall hedge borders the sidewalk for twenty yards or so, creating a shady, sheltered stretch of pavement. Special things happen there. On warmer evenings you get occasional curbside parties—a carload of teenagers, voices raised above a blaring radio. And during the day, crews from the electric company, telephone company, or city department of streets sometimes pull their trucks over and take a snooze. But the primary function of the stretch, and the most important one to know about if you’re a pedestrian, is to serve as a dumping ground for dog feces. Especially in the early evening, you see dog-owners walk their charges down to this piece of sidewalk, turn the other way for a moment or two (scanning the sky for early stars and trying not to think of dinner), then jerk the leash and head home. I’d guess this twenty-yard area services most of the dogs within a four- or five-block radius.

Having to regularly pick my way past the hedge makes me wonder. Why, while they slaughter other animals by the millions every day, are men so devoted to dogs, to the point of patiently standing by while these creatures answer the call of nature? Dogs are faithful, obedient, and easily pleased, I know, so they provide a buffer, or a substitute, for less reliable human companionship. Pigs and cows just aren’t as outgoing or affable, and even if they were, you still wouldn’t want them jumping into your lap. Perhaps, in addition, dogs aren’t as tasty as some other animals. Perhaps they don’t fatten as easily. Even if they did, we wouldn’t kill them. When I was growing up in Cleveland, I had a beagle named Geronimo, who was fat as a barrel. I’d never have butchered Geronimo. He was a member of the family.

However, while we have practical reasons for singling dogs out for special treatment, the Bhagavad-gita teaches us to see all living creatures equally. The Gita says that each living being is an eternal spirit soul, part and parcel of the Supreme Soul, Lord Krsna. All living beings, therefore, are members of Krsna’s family. Seeing equally doesn’t mean that we should shake hands with tigers or embrace rattlesnakes, but that we shouldn’t give unnecessary trouble to any soul. Even though cows, pigs, and chickens don’t make good house pets, they feel pain as much as dogs do. And by Krsna’s law of karma, whatever pain we give them we have to suffer in turn ourselves.

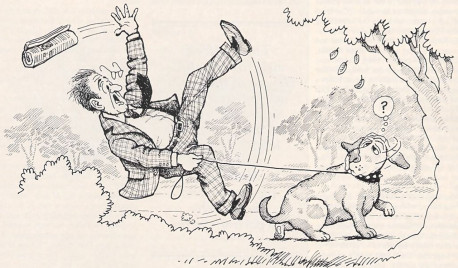

Each time I am obliged, because of inattention while ambling down the sidewalk, to hose off my shoes, I grow more curious about man’s infatuation with canines. One morning last week, after slipping on a particularly large deposit and nearly falling, I resolved to look deeper into this infatuation. Later that day, while shopping at the local Acme supermarket, I visited the dog-food section—aisle five, about the middle of the store. Dog food occupied all four shelves on one side of the aisle for almost the entire length of the aisle. (Cat food and kitty litter took up the remaining space.) I recognized Geronimo’s old favorites, Ken-1 Ration and Gravy Train, and I counted almost a dozen other brands, both dried and canned. Most brands were adorned with dog portraits, similar in some ways to the kid portraits on cereal boxes a couple of aisles over—both dogs and kids were portrayed as bright-eyed junior members of the family.

Dogs are junior members of God’s universal family, younger brothers to man, and therefore they are deserving of our care. But twelve brands of specially prepared food? Hugging a tiger is foolish, but so is spending so much for something that ends up on the sidewalk, or on the rug.

The dog-food aisle runs the full length of the store, where, set against the back wall, one finds an equally long display: the meat cooler. Chickens, turkeys, pigs, cows, and sheep. Why no portraits here? These are also family members—”children” of the Supreme Lord and man’s younger brothers and sisters. Like us, they have heads, necks, legs, hearts, livers, tongues (right there in the cooler, wrapped in cellophane). Like us they enjoy eating, sleeping, mating, and taking care of their young. Like us they know fear and pain. And like us they are eternal, individual spirit souls, mired in by flesh and bone. The only difference is that they have less intelligence and are therefore helpless before our butcher’s ax.

This wasn’t the first time I had contemplated man’s inconsistent policy toward animals, or the first time I’d seen how a supermarket exemplifies that policy. But on this supermarket visit, as I stood by the meat cooler, still vexed by my near fall on the sidewalk, I was militantly curious, asking myself, “How can people live with this and not go nuts?” On the human carnivore’s mental landscape, the aisle for the glorification of dog (and the sidewalk for the reception of his excrement) intersects with the aisle for the slaughter of other animals, yet the carnivore admits to no contradiction. Isn’t that a denial of the plain facts, of reality? And isn’t denial of reality bound to produce some kind of mental strain, or mental illness? Isn’t it in fact indicative of mental illness?

“Come off it!” says the carnivore. “Those animals are meant to be eaten. They’re meant to be killed. They’re food animals.”

“Meant by whom?” is the reply. “It’s obvious that you mean to kill and eat them, but where is the evidence of an intention other than yours? ‘Intend’ indicates there is a person intending, so who, besides you, is that?” Hardened criminals feel fully justified in doing what they do: their victims are meant to be victimized. But I don’t think animals are meant to be killed, and neither do the animals. Nor is the “meant to be” philosophy confirmed by any scriptural authority, although when the carnivores get their bloody hands on scripture, they naturally try to prove otherwise. The Vedic literatures say that flesh food is meant only for dogs and cats. So a man’s appetite for a dog’s food indicates that he’s not only infatuated with dogs, he emulates them. Any dog would be in seventh heaven sniffing around the grocery meat department.

But the meat cooler is not the last word in man’s schizoid policy toward his animal brothers. Walking down to the end of the meat section, I came to another cooler, this one running the length of the side wall and packed with milk and milk products. For the first five yards or 50, gallon and half-gallon milk containers are stacked three high and four deep, and cream and buttermilk fill the shelves above. Pint and half-pint containers—yogurt, sour cream, cottage cheese, and so on—fill the next section. After that there are butter and twenty kinds of cheese and, across the aisle, a freezer full of ice cream.

Now if the dog gets special treatment because he’s sociable, faithful, and eager to defend home and master, then why doesn’t the cow, who supplies the ingredient for this wealth of delicious food products, also receive special treatment? Not that we should keep one or two heifers at home and take them for walks around the block, or that our supermarkets should have an aisle of hay and oats. No. All we need do is stop cutting the cow’s throat. If you have to eat cow’s flesh, or any animal’s flesh, be patient. They all die in time.

Westerners deride the apparently irrational respect afforded animals, cows in particular, by followers of India’s Vedic literature. “Sacred cow” has come to indicate anything falsely held to be immune from reasonable criticism. It’s true the Vedic literature asserts that the cow is sacred—in the sense that she is especially favored by the Supreme Lord Krsna and that her care and protection by man lead to the development of higher, nobler qualities in human society. While this assertion is not immune from criticism, to prove it irrational we’d have to stop killing cows and observe for ourselves the effects of such a moratorium.

But sacredness aside for the moment, followers of the Vedic literature also point to the cow’s undeniable contributions—to those coolers full of milk, butter, and cheese, those freezers full of ice cream. We’ve all been enjoying milk and milk products ever since we were weaned. My two-year-old son consumes a quart of cow milk a day. That must be at least as much as he used to suckle. The dog may be our best friend, but the cow is our second mother. How much more a member of the family could she be?

The Vedas teach us to give protection not only to the cow, but to all living things, including dogs and cats. The Vedic injunction is mahimsyat sarva-bhutani: Do not harm any living thing. The Vedas even enjoin that as part of all great religious ceremonies, everyone in the community, including animals like cats and dogs, must be generously fed. Worship of God is complete only when all of His family members have been duly satisfied.

But the Vedic literature advises that we give special attention to the cow, because she nourishes us and because she assists us in spiritual advancement. She is useful in every respect. What to speak of milk, even cow dung has its uses—as fertilizer and in making fine incense, for example. That’s a lot more than you can say for dog feces.

Leave a Reply