The Biography of a Pure Devotee

by Srila Satsvarupa dasa Goswami

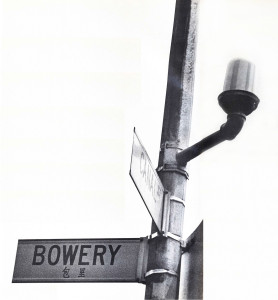

Now that Srila Prabhupada had left Seventy-second Street and had moved downtown, it wasn’t long before new people were coming to see him. ‘After a few minutes … the sound of the cymbals and the incense . . . we weren’t in the Bowery any longer. We started chanting Hare Krsna.. . . I remember it was relaxing and very interesting to be able to chant, and I found Swamiji very fascinating. . . .”

Now that Srila Prabhupada had left Seventy-second Street and had moved downtown, it wasn’t long before new people were coming to see him. ‘After a few minutes … the sound of the cymbals and the incense . . . we weren’t in the Bowery any longer. We started chanting Hare Krsna.. . . I remember it was relaxing and very interesting to be able to chant, and I found Swamiji very fascinating. . . .”

One of the first women to take an interest in Srila Prabhupada was twenty-year-old Carol Bekar. She came from an immigrant Catholic background, and she immediately associated Catholicism with the philosophy of bhakti-yoga. She was divorced and was now living with the brother of Carl Yeargens.

I had just come out of a marriage that failed [Carol relates], and I was trying to make some kind of a life for myself. Then I met Carl, and the Swami came. I think I was the first woman who approached his movement. The Swami’s attitude toward women was not difficult, but his teachings were difficult for some women. It wasn’t easy, especially in that era when things were so confused and highly political in this country. I think the major problem for the small group that went to see him on the Bowery was how we were going to translate his ideas into the context of New York City, 1966. He didn’t seem to think there needed to be much adjustment.

One time there was discussion of Arjuna deciding to go to war. It was difficult for Arjuna to decide, because war meant taking life. But Krsna convinced him that if it is in the service of God it is allowed. People found that idea very difficult to accept, because the controversy in Vietnam was beginning to heat up. People wanted to know the political ramifications of his religious doctrines. But he wasn’t interested in that. Of course, everyone was very reverential to him, but none of us had the background in the scriptures and the philosophy.

It was a very interracial, music-oriented scene. There were a few professional musicians, and a lot of people who enjoyed playing or just listening. Some people were painting in some of the lofts, and that’s basically what was going on. We had memorable kirtanas. One time there was a very beautiful ceremony: Some of us went over early to prepare for it. There must have been a hundred people who came that day.

Whenever he had the chanting, the people were fairly in awe of the Swami. On the Bowery, a kind of transcendence came out of the ringing of the cymbals. He used the harmonium, and many people played hand cymbals. Sometimes he played the drum. From the very beginning, he stressed the importance of sound and the realization of Godhead through sound. That was, I suppose, the attraction that these musicians found in him—the emphasis on sound as a means for attaining transcendence and the Godhead. But he wanted a serious thing. He was interested in discipleship.

Chanting and Cooking

Almost all of Prabhupada’s Bowery friends were musicians or friends of musicians. They were into music—music, drugs, women, and spiritual meditation. Because Prabhupada’s presentation of the Hare Krsna mantra was both musical and meditative, they were automatically interested. But they were interested in it more as Indian meditation music than as a way of worshiping God as the Supreme Person by chanting His name. Prabhupada stressed that all the Vedic mantras (or hymns) were sung—in fact, the words Bhagavad-gita meant “the Song of God.” But the Vedic songs had words, and these words were sound incarnations of God in the form of His name. The musical accompaniment of hand cymbals, drum, and harmonium was just that—an accompaniment—and had no spiritual purpose independent of the chanting of the name of God. Prabhupada allowed any instrument to be used, as long as it did not detract from the chanting.

Almost all of Prabhupada’s Bowery friends were musicians or friends of musicians. They were into music—music, drugs, women, and spiritual meditation. Because Prabhupada’s presentation of the Hare Krsna mantra was both musical and meditative, they were automatically interested. But they were interested in it more as Indian meditation music than as a way of worshiping God as the Supreme Person by chanting His name. Prabhupada stressed that all the Vedic mantras (or hymns) were sung—in fact, the words Bhagavad-gita meant “the Song of God.” But the Vedic songs had words, and these words were sound incarnations of God in the form of His name. The musical accompaniment of hand cymbals, drum, and harmonium was just that—an accompaniment—and had no spiritual purpose independent of the chanting of the name of God. Prabhupada allowed any instrument to be used, as long as it did not detract from the chanting.

For the Bowery musicians, sound was spirit and spirit was sound, in a merging of music and meditation. But for Prabhupada music without the name of God wasn’t meditation at all; it was sense gratification, or at most a kind of stylized impersonal meditation. But he was glad to see the musicians coming to play along in his kirtanas, to hear him, and to chant responsively. Some, having stayed up all night playing somewhere on their instruments. would come by in the morning and sing with the Swami. He did not dissuade them from their focus on sound; rather, he gave them sound. In the Vedas, sound is said to be the first element of material creation; the source of sound is God, and God is eternally a person. Prabhupada’s whole emphasis was on getting people to chant God’s personal, transcendental name. Whether they took it as jazz, folk music, rock, or Indian meditation made no difference, as long as they began to chant Hare Krsna.

Sometimes Carol Bekar would go shopping with Srila Prabhupada in nearby Chinatown, where he would purchase ingredients for his cooking. He would cook and at the same time teach and supervise others.

He used to cook with us in the kitchen [Carol Bekar continues], and he was always aware of everyone else’s activities in addition to his own cooking. He knew exactly how things should be. He washed everything and made sure everyone did everything correctly. He was a teacher. We used to make capatis by hand, but then one day he asked me to get him a rolling pin. I brought my rolling pin, and he appropriated it. He put some men on rolling capatis and supervised them very carefully

I made a chutney for him at home. He always accepted our gifts graciously, although I don’t think he ever ate them. Perhaps he was worried we might put something that wasn’t allowed in his diet. He used to take things from me and put them in the cupboard. I don’t know what he finally did with them, but I am sure he didn’t throw them away. I never saw him eat anything that I had prepared, but he accepted everything.

Serious Newcomers

Most of the Swami’s visitors would call in the evening. The loft was quite out of the way, and it was on the Bowery. A cluster of sleeping derelicts regularly blocked the street-level entrance, and visitors would find as many as half a dozen bums to step over before climbing the four flights of stairs. But it was something new; you could go and sit with a group of hip people and watch the Swami lead kirtana. The room was dimly lit, strange, and impressive; and Prabhupada would burn incense. Many casual visitors came and went. One of them—Gunthar—had vivid impressions.

Most of the Swami’s visitors would call in the evening. The loft was quite out of the way, and it was on the Bowery. A cluster of sleeping derelicts regularly blocked the street-level entrance, and visitors would find as many as half a dozen bums to step over before climbing the four flights of stairs. But it was something new; you could go and sit with a group of hip people and watch the Swami lead kirtana. The room was dimly lit, strange, and impressive; and Prabhupada would burn incense. Many casual visitors came and went. One of them—Gunthar—had vivid impressions.

You walked right off the Bowery into a room filled with incense [Gunthar relates]. It was quiet. Everyone was talking in hushed tones, not really talking at all. Swamiji was sitting in front of the room, in meditation. There was a tremendous feeling of peace which I had never had before in this context. I d happened to have studied for two years to become a minister and was into meditation, study, and prayer. But this was my first time to do anything Eastern or Hindu. There were lots of pillows around and mats on the floor for people to sit on. I don’t think there were any pictures or statues. It was just Swamiji, incense, and mats, and obviously the respect of the people in the room for him.

Before we went up, Carl was laughing and saying how Swami wanted everyone to use the hand cymbals just correctly. I had never played the cymbals before, but when it began I just tried to follow Swamiji, who was doing it in a certain way. Things were building up, the sound was building up, but then someone was doing it wrong. And Swamiji just very, very calmly shook a finger at someone, and they looked, and then everything stopped. He instructed this person from a distance, and this fellow got the right idea, and they started up again. After a few minutes… the sound of the cymbals and the incense … we weren’t in the Bowery any longer. We started chanting Hare Krsna. That was my first experience in chanting—I’d never chanted before. There’s nothing in Protestant religion that comes even close to that. Maybe Catholics with their Hail Mary’s, but it’s not quite the same thing. I remember that it was relaxing and very interesting to be able to chant, and I found Swamiji very fascinating.

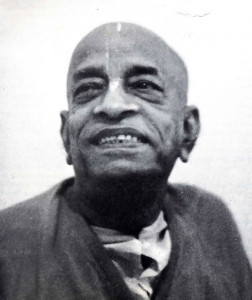

The loft in the Bowery was more open than Prabhupada’s previous quarters and Prabhupada had lost some of his privacy. Now some of the visitors were skeptical and even challenging, but everyone found the Swami confident and joyful. Some of them could see that he had a far-reaching plan for spreading Krsna consciousness. He knew what he wanted to do and was singlehandedly carrying it out. “It is not one man’s job,” he would say. But Prabhupada went on doing all he could, depending on Krsna for the results. David was beginning to help, and more people were coming to visit him.

One of the most serious newcomers was a boy named Michael Grant. Mike was twenty-four. His father, who was Jewish, owned a record shop in Portland, Oregon, where Mike grew up. After studying music at Portland’s Reed College and at San Francisco State, Mike, who played the piano and many other instruments, moved to New York City, along with his girlfriend, hoping to get into music professionally. But he quickly became disenchanted with the commercial music scene. Playing in nightclubs and pandering to commercial demands seemed particularly unappealing. In New York he joined the musicians’ union and worked as a music arranger and as an agent for several local groups.

“He Wasn’t in a Hurry”

Mike lived on the Bowery in an A.I.R. loft on Grand Street. It was a large loft where musicians often congregated for jam sessions. But as he turned more and more to serious composing, he found himself retiring from the social side of the music scene. His interests ran more to the spiritual, quasi-spiritual, and mystical books he had been reading. He had encountered several svamis, yogis, and self-styled spiritualists in the city and had taken up the regular practice of hatha-yoga asanas (sitting postures). From his first meeting with the Swami, Mike was interested and quite open, as he was with all religious persons. He thought all genuinely religious people were good, although he did not care to identify with any particular group.

There was a little bit of familiarity [Michael Grant relates] because I had seen other svamis. The way he was dressed, the way he looked—older and swarthy—weren’t new to me. But at the same time there was an element of novelty. I was very curious. I didn’t hear him talk when I first came in—he was just chanting—but I mainly was waiting to hear what he was going to say. I had heard people chant before. I thought, why else would he put himself in such a place, without any comforts, unless the message he’s trying to get across is more important than his comfort? I think the thing that struck me most was the poverty that was all around him. This was curious, because the places that I had been before had been just the opposite—very opulent. There was the Vedanta center in upper Manhattan and others. They were filled with staid, older men with their leather chairs and pipe tobacco-that kind of environment. But this was real poverty. The whole thing was curious.

Prabhupada looked very refined, which was also curious—that he was in this place. When he talked, I immediately saw that he was a scholar and that he spoke with great conviction. Some statements he made were very daring. He was talking about God, and this was all new—to hear someone talk about God. I always wanted to hear someone I could respect talk about God. I always liked to hear religious speakers, but I measured them very carefully. So when he spoke, I began to think, “Well, here is someone talking about God who may really have some realization of God.” He was the first one I had come across who might be a person of God, who could feel really deeply.

I went up to him afterwards. I had the same feeling I’d had on other occasions when I d been to hear famous people in concerts. I was always interested in going by after concerts to see musicians and singers just to meet them and see what they were like. I had a similar feeling after Prabhupada spoke, so I went up and started talking. But the experience was different from the others in that he wasn’t in a hurry. He could talk to me, whereas with others all you could do was get in a few words. They were always more interested in something else. But he was a person who was actually showing some interest in me as a person, and I was so overwhelmed that I ran out of things to say very quickly. I was surprised. Our meeting broke off on the basis of my not having anything further to say. It was just the opposite of so many other experiences, where some performer would be hurrying off to do something else. This time, I was the one who couldn’t continue.

Prabhupada liked to take walks. Directly across the street from his doorway at 94 Bowery was the Fulton Hotel, a five-story flophouse. Surrounding him were other lower Manhattan lodging houses, whose tenants wandered the sidewalks from dawn till dark. An occasional flock of pigeons would stir and fly from one rooftop to the next or down to the street. Traffic was heavy. The Bowery was part of a truck route to and from Brooklyn by way of the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges.

The Bowery sloped gently downhill toward the north, and Prabhupada could see the street lights and traffic signals as far up as Fourth Street. He could see Con Edison with its prominent clock tower, and—on a clear day—the top of the Empire State Building on Thirty-fourth. There were signboards and a few scraggly Manhattan trees.

Prabhupada would walk alone in the morning through the neighborhood. May 1966 saw more rain than normal, and he carried an umbrella. Sometimes he walked in the rain. He was not always alone; at times he walked with one of his new friends and talked. Sometimes he shopped. Bitter melon, dal, hing, chick-pea flour, and other “specialty foods” common in Indian vegetarian cuisine were available in Chinatown’s nearby markets.

On leaving the loft, Srila Prabhupada would walk south a few steps to the corner of Bowery and Hester Street. Turning right on Hester he would immediately be in Chinatown, where the shops, markets, and even the Manhattan Savings Bank were identified by signs lettered in Chinese. Sometimes he would walk one block further south to Canal Street, with its Central Asian Food Market and many other streetside fruit and vegetable markets. In the early morning the sidewalks were almost deserted, but as the shops began to open for business the streets became crowded with local workers. shopkeepers, tourists, and aimless derelicts. Parked cars lined both sides of the street; the crowds of pedestrians and lanes of traffic passed tightly; the winding side streets of Chinatown were lined with hundreds of small stores. A brass Confucius, discolored with age and suffering from neglect, stood on Chatham Square.

Srila Prabhupada’s walks on Hester would sometimes take him into Little Italy. which overlaps Chinatown at Mulberry Street. In this neighborhood, places like Chinese Pork Products and the Mee Jung Mee Supermarket stood alongside Umberto’s Clam House and the Puglia Restaurant, advertising capucino a la puglia, coffee from Puglia.

His walks west of Bowery, in Chinatown and Little Italy, were mainly for shopping. Yet on occasions he walked in the opposite direction as far as the East River and the Brooklyn Bridge. It was a dangerous neighborhood, however, and when a friend warned him about a sniper who had been firing at strollers along the river, Srila Prabhupada stopped going there.

Despite the bad neighborhood where Srila Prabhupada lived and walked, he was rarely disturbed. Often he would find several Bowery bums asleep or unconscious at his door, and he would have to step over them. Sometimes a drunk, simply out of inability to maneuver, would bump into him, or a derelict would mutter something unintelligible or laugh at him. The more sober ones would stand and gesture courteously, ushering Prabhupada into or out of his door at 94 Bowery. Prabhupada would pass among them, acknowledging their good manners as they cleared his path.

Certainly few of the Bowery men and others who saw him on his walks knew much about the small, elderly Indian sadhu, dressed in saffron and carrying an umbrella and a brown grocery sack.

Sometimes Srila Prabhupada would meet one of his new friends on the street. He met Janet, Michael Grant’s wife, on several occasions.

I would see him [Janet relates] in the midst of this potpourri of people down there, walking down the street. He always had an umbrella, and he would always have such a serene look on his face. He would just be taking his afternoon jaunts, walking along, sometimes stepping over the drunks. And I would always get sort of nervous when I would meet him on the sidewalk. He would say, “Are you chanting?” And I would say, “Sometimes. And then he would say; “That’s a good girl.”

Leave a Reply