I, who had worshiped so long at the shrine of the Bard,

now astounded myself by thinking, “This is greater than Shakespeare!”

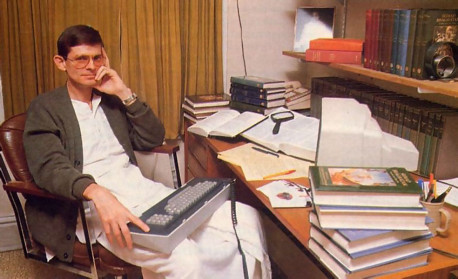

by Ravindra-Svarupa Dasa

RAVINDRA-SVARUPA DASA, a devotee of Krsna for fourteen years, holds a doctorate in religion from Temple University. The above article is from the Preface to the author’s forthcoming hook. Encounter with the Lord of the Universe, a collection of the author’s articles, reprinted from BACK TO GODHEAD.

By the time I encountered the Krsna consciousness movement. I was so eager to transcend material existence that I was willing to renounce practically everything for the sake of liberation. So convinced was I that pain and suffering were of the essence of this life that I did not desire to reserve any attachment, even to the highest and best part of it.

And to me, that highest and best was exemplified in art and literature—in those timeless artifacts, those “monuments,” as the poet Yeats beautifully called them, “of unaging intellect.” And I myself had since adolescence sought transcendence in the role of the artist. I had become captivated by a certain image of the artist, an image presented with consummate lyricism by James Joyce in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: a “fabulous artificer . . . forging anew in his workshop out of the sluggish matter of the earth a new soaring impalpable imperishable being.”

A magus turning matter into spirit, the artist transmutes the tacky, mortal stuff of this life into a new “unaging,” “imperishable” creation; in so doing, he redeems his existence from time and change. Certainly this redemptive drive toward the eternal and immutable is the deepest motive of art. As such, the artistic impulse is religious. The problem is that it fails. It is bad religion.

Consider this typical example of the “eternizing theme” from one of Shakespeare’s sonnets:

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou owest,

Nor shall Death brag thou wand’rest in his shade

When in eternal lines to Time thou growest.

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

The poet refers to his verse as eternal—as eternal as Time itself—yet in the final couplet a more deflated view prevails: the verse can at best last no longer than mankind. And while the poet boldly asserts that his verse rescues his subject from time and death, preserving him in eternal youth, we recognize a rhetorical fiction, a hyperbole. Centuries ago that fair youth moldered in his grave and is now at most a sparse handful of dust. Nothing has really been saved from time and death: not the poet, not his subject, not his art.

The promise of art is illusory. Art cannot save us, no matter how beautiful and well wrought its objects may be. They are, essentially, fictions. At best, art may palliate the pains of life, but even in this it dangerously misleads. They say that during the Holocaust, Jews were marched toward gas chambers while an orchestra beguiled them with Mozart and Brahms. Aesthetic enjoyment is like an anodyne that relieves the symptoms of a disease. Given the illusion of health, we can ignore our sickness, and eventually it destroys us.

The spell of art is hard to break once you have fallen under it, but I became at last disenchanted. Although I was still deeply attracted by great art and literature and still strongly felt the allure of the artistic vocation, I knew neither the enjoyment nor the creation of art could save me from death, I began to study spiritual writings, and eventually I became sure of at least this much: that material life is essentially suffering, that suffering is caused by our desires, and that the cure for suffering lies in the uprooting of our desires. I was willing, therefore, to give up everything, from the gross satisfaction of animal appetites to the refined pleasures of art and its creation. I set out on my own to eradicate my desires. I failed utterly.

I failed because my idea of renunciation was rudimentary, incomplete. I did not actually understand renunciation, in principle or in practice. Finally, however, I was enlightened in this matter by the devotees of Krsna. As they explained it, the Krsna conscious method of renunciation was both sensible and practical. And, as I soon discovered, it was remarkably efficacious. Moreover—and this astonished me completely—it was joyful through and through. It was not negation but fulfillment. And whatever I gave up on the material platform, I got back a thousandfold on the spiritual. In my case, this was most immediately evident with reference to literary art.

I had gleaned my previous ideas of renunciation from the teachings of various impersonalists, those mystics who think that ultimate truth is wholly devoid of names, forms, attributes, activities, and relations and that to characterize it properly we must resort to silence and negation. They hold that in the liberated state the knower, the known, and the act of knowing coalesce to absolute unity and that to enter that state we must denude ourselves of all personality and individuality and turn away from all sensory and intellectual experience. This bleak and daunting prospect can appeal only to the most burned-out victims of time, and it has sent many seekers back to material life in frustration.

But Rupa Gosvami, a great authority on devotional service, calls this impersonal sort of renunciation phalgu-vairagya, “incomplete renunciation.” It is incomplete because the realization of the supreme on which it is based is incomplete. By rejecting material qualities, names, forms, activities, and relations, the impersonalists have reached but the outer precincts of divinity, which they report to be an endless, undifferentiated spiritual effulgence. But they do not know that this effulgence conceals a still higher region of transcendence, where the Supreme Personality of Godhead Krsna resides. In this topmost abode, hidden in the heart of the infinite ocean of light, Krsna exhibits His most beautiful transcendental form and His unsurpassable personal qualities as He plays out endless exchanges of love with His pure devotees. Because the impersonalists have unfortunately not yet realized these variegated positive features of transcendence, they must be content with mere negation of the material.

When there is complete realization of the supreme, however, one enters the luminous realm of devotional service. Here, the senses and mind of the devotee become decontaminated from all material taint by complete absorption in the active service of their transcendental object, Krsna. In this way there is the awakening of full spiritual existence, and material existence automatically ceases. Accordingly, the devotee does not reject mind and senses, desire and activities, but he restores them to their original purity through the devotional activities of Krsna consciousness. Because the devotee focuses his full attention on the supremely attractive forms and pastimes of Krsna, he quite naturally loses his interest in all the attractions of this world. In comparison with Krsna and His society, those attractions undergo fatal devaluation.

The foremost book dedicated wholly to Krsna is the Srimad-Bhagavatam. Srimad-Bhagavatam is filled with accounts of the marvelous activities the Lord performs during His various descents into this world. It narrates His eternal, joyful pastimes in His supreme abode, and it describes in detail how he dwells as Supersoul within our hearts. With scientific precision, Srimad-Bhagavatam tells how Krsna again and again brings forth and maintains and winds up the creation. It tells of the great adventures of His devotees throughout the universe. And it instructs us in the potent practices of bhakti-yoga, by which we can regain our transcendental organs of perception and once again see Krsna always, within everything and beyond everything. The works comprising India’s vast spiritual literature are called the Vedic literature, and the Srimad-Bhagavatam is “the ripened fruit of the Vedic tree of knowledge.” Yet this work was hardly known outside of India until His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, my spiritual master, began his hugely successful project of translating it and distributing it all over the world.

The first time I read Srimad-Bhagavatam was one of the high points of my life. In those days, we had only the three russet volumes Srila Prabhupada had written and published in India and brought with him to America. But these books—crudely printed, badly bound, riddled with typos—were the greatest literature I had ever encountered. I, who had worshiped so long at the shrine of the Bard, now astounded myself by thinking, “This is greater than Shakespeare!” I read with full appreciation that one of Krsna’s names is Uttamasloka, or “He who is praised by immortal verse.” I delved deeper and deeper into the Bhagavatam, endlessly fascinated, and discovered one day that I had in the process renounced the literature of this world.

Srimad-Bhagavatam is in a class all its own, and once you have acquired a taste for it, all mundane literature seems stale and flat. Nor do you tire of the Srimad-Bhagavatam. As a rule, the higher the quality of a literary work, the more it bears rereading. A paperback thriller is notably unthrilling on second reading;

Hamlet or King Lear remain satisfying after many revisits. Still, there are limits, and even the most ardent Shakespearean requires periodic relief. But you can pick up Bhagavatam every day and find it inexhaustible; with each rereading it increases in interest. Because Bhagavatam is simply not a product of this world, it has the ever-fresh quality that is the hallmark of spirit.

All along I had really wanted Srimad-Bhagavatam. It seemed to me that all literary yearnings for the eternal unconsciously seek that crest-jewel of books. And now I had found it. So I did not, after all, have to give up my attraction to literature; I had only to purify it. Once purified, my desire was satisfied beyond my greatest expectation.

In the same way, my desire to write was also fulfilled. In becoming Srila Prabhupada’s disciple, I had become part of a distinctively literary spiritual tradition. The historical line of spiritual masters to which Prabhupada belongs is named the Brahma-sampradaya, after its first member, the cosmic engineer. Lord Brahma. At the beginning of creation Brahma was impregnated with Vedic knowledge by Krsna, and Brahma then arranged for this knowledge to be passed down carefully from generation to generation through an unbroken chain of masters. Lord Brahma is often depicted with a book in his hand, signifying his possession of Vedic knowledge, and his sampradaya, preserving its founder’s characteristic, is particularly learned. Its members are so distinguished for literary production that it is known as “the sampradaya of the book.” Thus, Srila Prabhupada himself made books the basis of his preaching effort, and he gave the world more than sixty volumes of spiritual writings.

Not long after I moved into the temple, I heard these instructions from Srila Prabhupada, on tape from a lecture in Los Angeles: “Every one of you, what is your realization? You write your realization—what you have realized about Krsna. That is required. It is not passive; always you should be active. Whenever you find time, write. Never mind—two lines, four lines, but you write your realizations. Sravanam, kirtanam—writing or offering prayers, glories—this is one of the functions of a Vaisnava [devotee]. You are hearing, but you have to write also. Then, writing means smaranam—remembering what you have heard from your spiritual master.” Thus, writing automatically involves a devotee in three prominent aspects of devotional service: hearing and chanting about Krsna and remembering Him [sravanam, kirtanam, and smaranam]. And in a letter to a disciple, Prabhupada said: “All students should be encouraged to write some article after reading the Bhagavad-gita, Srimad-Bhagavatam, and Teachings of Lord Caitanya. They should realize the information, and they must present their assimilation in their own words. Otherwise, how can they become preachers?”

Moreover, Prabhupada specifically established BACK TO GODHEAD magazine in America to provide his disciples with an outlet for their writings. So I had abundant encouragement. And I had inexhaustible material. There was nothing else to do but write.

Srimad-Bhagavatam recounts the occasion when the great sage Narada Muni had cause to instruct his disciple Vyasadeva concerning the principles of devotional service. Narada says: “O brahmana Vyasadeva, it is decided by the learned that the best remedial measure for removing all troubles and miseries is to dedicate one’s activities to the service of the Supreme Lord Personality of Godhead, Sri Krsna. O good soul, does not a thing, applied therapeutically, cure a disease which was caused by the very same thing? Thus when all a man’s activities are dedicated to the service of the Lord, those very activities which caused his perpetual bondage become the destroyer of the tree of work.” (Italics added.)

My own experience confirms these words of Narada Muni. Certainly my intense desire to enjoy and create fine literature had bound me tightly to this world. But when I became a devotee, the very desire that had caused my bondage, when dovetailed in the service of Krsna, produced freedom. I experienced early the purifying, liberating effect of writing in Krsna consciousness.

Writing, for me, demands great concentration. In practically no other circumstances am I compelled to meditate so intensely on Krsna and His teachings; in so doing I associate with Krsna and by that association become purified. Moreover, the effort to write clearly is the effort to understand clearly. When I see my words out there, all detached on the page, it is as if they stand exposed for judgment. And I hasten to revise and revise and revise again. In reworking and refining my writing, I feel I am being reworked and refined. In this way, writing keeps me fixed in the refiner’s fire of Krsna consciousness.

I said earlier that the ambition to attain the eternal and immutable is the deepest motive of art. In the case of Krsna conscious art, this drive can realize its end. Krsna is eternal, and whatever comes into contact with Him attains that same eternal nature. The literary artist who dedicates his craft fully to the service of Krsna, then, really does transmute matter into spirit, and he becomes redeemed fully from time and change. His work may be more or less expert in the world’s judgment, but that matters not at all. As Srila Prabhupada noted in this connection, “If one is actually sincere in writing, all his ambitions will be fulfilled.”

Leave a Reply