Discovering The Culture of the Soul

A young Canadian moves from Judaism to rock music to the rat race

before a chance encounter opens the door to “a different world.”

by Vaiyasaki Dasa

I grew up in the Canadian Midwest in Winnipeg, a city of half a million people. I was Jewish, and my early education was steeped in the lore and culture of Judaism. Weekly my mother would send me for my violin lesson and dance class. At age thirteen I was duly confirmed, and I feelingly sang the Hebrew prayers at my Bar Mitzvah, with a voice cracking intermittently because of puberty. As is the custom, some people said it was the best they’d ever heard.

I grew up in the Canadian Midwest in Winnipeg, a city of half a million people. I was Jewish, and my early education was steeped in the lore and culture of Judaism. Weekly my mother would send me for my violin lesson and dance class. At age thirteen I was duly confirmed, and I feelingly sang the Hebrew prayers at my Bar Mitzvah, with a voice cracking intermittently because of puberty. As is the custom, some people said it was the best they’d ever heard.

Our family would meet regularly at my Uncle Mike’s home, where we would dutifully observe the High Holy Days, especially Passover and Hanukkah. This was a necessity in our family. We were maintaining the tradition, because to be a Jew was considered a privilege. Not that my mother looked down on Gentiles; rather, she readily mixed with people of all faiths and made friends with them. Our Jewish culture was our way of life, of course, but it was mainly concerned with the external concept of being Jewish. God was rarely discussed.

As I entered my teenage years, my cultural perspective changed. I gave up the violin, which I had studied for six years, and took up the guitar. I started playing rock ‘n’ roll and blues. Since my father had abandoned his responsibility to the family and had gone off on his own merry way, I had no one around to explain to me what was happening. My senses were becoming wild.

It wasn’t long before everybody knew me as a rock guitarist gigging around town with various bands. The family was embarrassed. My mother tried to dissuade me, but she was unable to give proper guidance, partly because of my stubborn nature and partly because of her liberal attitude. She had always wanted me to become accomplished at music—but not like this!

Having already completely rejected the culture in which I had been born, nurtured, and educated, I now embraced the rock culture. My young senses were awakening, and I wanted to experience new sights and sounds and ideas. And my Jewish culture was unable to provide them. My new way of life, although strange to my family, was very exciting and challenging to me.

“It’ll never last,” my mother used to say about my music, “It’s just a passing fad. You should take up something more worthwhile and lasting.” Prophetic words, though they fell on deaf ears. Still, I couldn’t really become a part of the rock music scene, because it was too jaded for my sensibilities. Outwardly I appeared to be a part of the scene, but inside I was a different person—a person who was becoming more and more dissatisfied with life.

By the time I reached my early twenties I was completely bored with everything. Nothing gave me a sense of fulfillment—not my rock music, not my college, and not my girl friend, what to speak of my Jewish family tradition, which I had rejected years ago. I was feeling culturally bereft. Still, I figured I had to make money, so I packed my bags and left for Toronto, where I applied for a job with IBM. After passing a barrage of tests. I was accepted into the IBM family of computer programmers, or “hackers,” as they’re known in the trade.

Two years in the business world as a young man on the way up didn’t inspire me either, though I vainly tried to enjoy my new-found wealth. I was bored with associates talking about Fortran and bytes of core storage. Again those feelings of dissatisfaction overtook me. Before, when I was living at home, my mother would often lament, “Why can’t you ever stick to anything? Use your intelligence and do something with your life.” Now I was bored with computers and wanted to leave. But I didn’t know where to go or what to do.

I had experienced life in several widely varying cultural milieus, but without finding satisfaction. My soul was crying for some deeper expression, but society could not provide the outlet. Although I loved music, I couldn’t find a sense of purpose in what I was playing. Computers were interesting, but my job wasn’t anything more to me than just a way to earn a living. It seemed I had come to a dead end.

One day during the summer of 1968, my supervisor gave me a new assignment: a Mr. Sen Gupta would be requiring my help to run his programs. Mr. Sen Gupta was from India, and I was interested to hear him speak about his life and culture and about his boyhood in a remote village. It was all new to me, and he piqued my interest with his mystical references to Krsna and his talk of childhood encounters with the occult. That all this talk was going on in the Toronto Data Center of IBM seemed incongruous to me. Understanding the inappropriateness of the situation, and feeling he had found a friend, Mr. Sen Gupta invited my girl friend and me to dinner at his home.

As soon as we walked in the door we were in a different world. As we followed our host into the living room, the fragrance of curry greeted us. We sat down, and as I sank into the comfortable sofa, I glanced around the room. The pictures on the wall immediately evoked a culture both distant and ancient. Mrs. Sen Gupta came in from the kitchen, greeted us with smiles, sweet words, and cordial Indian gestures, and then returned to finish the last bit of cooking.

My girl friend and I began chatting with Mr. Sen Gupta. When my girl friend mentioned that she had seen shaven-headed youths playing drums and chanting Hare Krsna in San Francisco during the summer, our host replied, “Oh, they are Vaisnavas.” Although I had never heard the word before, somehow it stuck in my mind.

Our host explained that these were devout followers of Caitanya Mahaprabhu, a sixteenth-century saint who propagated the chanting of the names of God as the best way to achieve God consciousness in this lifetime. “At home in Bengal,” our host continued, “this chanting and dancing is a common sight. Bengali Vaisnavas accept that Caitanya Mahaprabhu is an incarnation of Lord Krsna.” It never occurred to me at the time that Mr. Sen Gupta was also a Vaisnava.

All of a sudden Mrs. Sen Gupta walked into the room carrying a tray with several exotic-looking dishes. She walked right past us and placed the tray on the mantle-piece before an attractively framed picture. She folded her palms and closed her eyes. “She’s saying a prayer,” our host informed us, as we stared with great interest at this unfamiliar custom. After a few moments, she returned with a smile to inform us that dinner was ready.

The vegetarian meal was completely new to us, and we liked it. Although I didn’t know it at the time, we were being served prasadam, which means “the mercy of Krsna.” Vaisnavas prepare all food with the consciousness that it is for the pleasure of God. Then it is offered with devotion to Krsna, who accepts the offering of love from His devotees. The food, coming in contact with the Supreme Pure, becomes spiritualized. It’s a similar idea to the Holy Eucharist of Christianity, except instead of a wafer, you get a banquet of sumptuous vegetarian cuisine cooked with exotic spices and herbs. Unknowingly, I was experiencing the culture of Krsna consciousness from an authentic Bengali Vaisnava. Over a hot cup of herbal tea, our host informed us that every Sunday they would get together with other Indian families at a rented hall downtown. “We use it for our temple,” he said. He asked if we would like to visit, and we said we would.

The next Sunday afternoon we drove downtown, following the directions Mr. Sen Gupta had given us. When we got there we found an old three-story building, hardly what we had expected an Indian temple to look like. We climbed two flights of stairs, until we came to a door marked with a three. Opening the door, we entered an auditorium with rows of pews and, at the far end, a small stage. Rhythmic music emanated from the stage. Although we were careful to enter quietly, almost everyone turned to look at us as we took our seats.

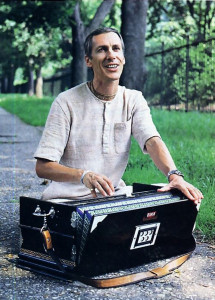

From our seats we watched the musicians sitting cross-legged on the stage. One man pumped a harmonium and sang in a moving voice, while the others played drums and hand cymbals and responded in chorus. As I listened intently, trying to follow the melody and rhythm, I gradually caught on; they were chanting Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare.

Unexpectedly, a wave of emotion swept over me and I began shedding tears. Overcome by the mood, I closed my eyes. I had been involved with music all my life—why was this affecting me so strongly? Allowing the sound vibrations to enter into me, I wondered at the beauty of it all. After a few moments, I looked over to my girl friend to see how she liked it. She smiled and nodded.

When the musicians stopped playing, everyone acknowledged our presence with a polite greeting. Although we were the only Westerners present, we felt at ease. Soon the singing started again, and after some time we decided to leave. Quietly, we tiptoed out the back and down the stairs.

The next time Mr. Sen Gupta came by the office, we spoke only briefly, but I told him that I had enjoyed the Sunday program. His work at IBM was almost finished, however, and we hardly saw each other again. I began reading books on yoga and philosophy. Before long I became a vegetarian, and I began meeting other people who were also seeking something more substantial in life.

From time to time I would come across the Hare Krsna devotees chanting on street corners and distributing their magazine. It was always pleasing to hear the rhythmic chiming of hand cymbals and then round a corner to find robed and shaven-headed youths chanting the familiar Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, and dancing. Occasionally they would offer me a BACK TO GODHEAD magazine, but I had my own philosophy. Besides, I figured I knew what their beliefs were. I understood they had adopted a life of simplicity and chanting as a means of spiritual realization, so I accepted them as brothers.

A few years passed, and I moved to London. One summer’s day in 1972, as I was walking through Soho, I heard a familiar sound—ting, ting, ting, ting, ting, ting. As I rounded the corner onto Oxford Street, there they were: the Hare Krsna devotees, chanting and wending their way through the crowds of shoppers and tourists, bringing a little music and their magazine to the noisy city streets.

It was like meeting an old friend. A smile appeared on my face as they danced by me. They’re here too, I mused, and I remembered my exchanges with Mr. Sen Gupta and the chanting at the Indian temple years ago. From my own experiences I knew that an ancient culture was being transplanted in the West, much the same as Christianity had been exported to India.

Later one devotee, Prabhavisnu dasa, helped me to grasp the importance of the chanting of Hare Krsna. He explained that, according to the five-thousand-year-old Vedic scriptures, the chanting of the holy names of God cleanses the heart of lust, anger, greed, envy, madness, and illusion. Thus the original consciousness of the soul is uncovered and one’s dormant love for God is automatically revived. This is possible because God and His holy name are nondifferent. I was personally able to experience the power of the chanting of Hare Krsna, and the results were very satisfying.

After almost a year of visiting the London Hare Krsna temple and associating with the devotees, reading the translations of the Vedic writings by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, and observing the four basic restrictions for all devotees—no meat-eating, no intoxication, no illicit sex, and no gambling—I came to several important realizations. First, I realized that the Krsna devotees were much more committed to spiritual life than anyone else I had come across. They didn’t offer mere lip service, nor was their spiritual practice a part-time engagement. Rather, they wholly dedicated themselves to the devotional service of God in every aspect of their lives.

Second, unlike traditional Hinduism, which is polytheistic, Krsna consciousness is monotheistic, with a clear conception of a personal God.

Third. I realized that the philosophy of Krsna consciousness is extremely profound and deals with ontological concepts of God and His creation not found in other faiths.

I was impressed by the devotees, not only by their deep understanding of spiritual truths hut also by their kindliness. Resolving to fully experience Krsna consciousness and recalling the ecstatic, attractive chanting and friendliness of a devotee I had met back in Toronto (Visvakarma dasa), I flew back to Canada and moved into the Toronto temple.

By the summer of 1975, I felt an irresistible desire to go to India and experience first-hand the roots of the Krsna religion. Arriving in West Bengal, I immediately fell in love with this tropical land and its people, and I recalled my exchanges with Mr. Sen Gupta. I was now in his homeland, where almost everyone was a devotee of Krsna! The people accepted me as a fellow Vaisnava, and many invited me into their homes as an honored guest. They were charmed to see that I had so fully imbibed their culture.

Everywhere I went, the chanting of Hare Krsna was accepted as the means to spiritual salvation. This was especially true in the rural areas, which were dotted with many picturesque villages. Here the people lived simply and naturally in thatched bamboo cottages that reminded me of some South Pacific island paradise.

In Bengal, every village holds a yearly festival in which expert musical groups and singers are invited to sing the Hare Krsna mantra; it’s an age-old tradition. The custom is that the chanting must go on for three days without a moment’s break. This, they believe, produces a very auspicious atmosphere. Many people come from the neighboring villages to hear their favorite groups play. I also attended one such festival, and more than ever I was able to see that Krsna consciousness was an integral part of these people’s lives. It was also clear that these villagers, despite their simple lifestyle, were much happier than the anxiety-ridden men and women of modern Western cities.

From my study of Srila Prabhupada’s books and by my own realizations, I can understand that today’s mood of dissatisfaction in life comes from identifying the material body as our real self. Consequently, so much effort is spent in trying to squeeze out every last drop of pleasure from the body. Krsna consciousness, on the other hand, is based on the universal principle that life is eternal. The practice of Krsna consciousness reveals to us that we are not these bodies, but the spirit soul within. The spirit soul animates the otherwise lifeless body.

Because Krsna consciousness is the eternal culture of the soul, it is fully satisfying to everyone. Now I am applying my talents as a musician by playing and singing songs for the glorification of Krsna. (I haven’t given up my computer skills either. In fact, I wrote this article on a new microcomputer using Wordstar.) Krsna consciousness has been especially meaningful to me because it has freed me from the misconception that I am the body. And it has revealed to me the eternal principle that everyone is a spiritual soul, part and parcel of the Supreme Soul, Krsna.

Leave a Reply