“Find a Bona Fide Guru”

A young woman tells of her search for satisfying answers

in a world of hypocrisy and dead ends.

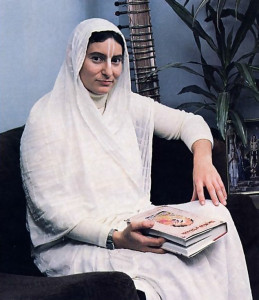

by Kamra-devi dasi

I entered Cornell University in the fall of 1971 at the age of seventeen, full of hopes, expectations, and innocent dreams. For the first time, I was away from my parents’ close jurisdiction. The new opportunity to associate with world-famous scholars and professors excited me, and I was looking forward to preparing for a career in veterinary medicine.

I entered Cornell University in the fall of 1971 at the age of seventeen, full of hopes, expectations, and innocent dreams. For the first time, I was away from my parents’ close jurisdiction. The new opportunity to associate with world-famous scholars and professors excited me, and I was looking forward to preparing for a career in veterinary medicine.

With my newly found freedom, it was only a few months before I had abandoned the strict moral principles my orthodox Jewish parents had tried to instill in me. I made new friends who, like me, had come to Cornell for a good education—and a good time. I was having fun doing things I knew my parents wouldn’t approve of, but something wasn’t right. I would go to parties where most of the kids were drinking or taking drugs, and I would see members of the faculty behaving just like the students. Here were my teachers challenging my intelligence, demanding me to study and to cultivate a deep love of knowledge, yet by their activities, they seemed to be indicating that life’s real goal lay in hedonism. So I was shocked to see that the enjoyment of the professors was on the same level as that of the students. And I began to question the value of working to attain a degree in veterinary medicine.

By the end of my first semester, I was already dissatisfied with dating, partying, hearing rock music, and getting intoxicated, and I wanted to apply myself to my studies. But the profound disillusionment I felt with my professors also disillusioned me about the life I was supposed to be working so hard to make for myself.

For example, my first biology course was taught by a well-known British professor, who began her introductory lecture by announcing to thirteen hundred students that she had a five-acre marijuana field in back of her house. The reactions of the students varied from cheering to booing, but for me this was another blow to my weakening faith.

As for my expanding freedom to enjoy ever-increasing sense pleasures, I realized that I would just become ever-increasingly dissatisfied. It was a syndrome: hankering for a bigger and better stereo system or more and better horses, or whatever happened to strike my fancy. I would have to work hard to achieve my goals, but upon achieving them, I would immediately become dissatisfied and have to work still harder to achieve an even more ambitious materialistic goal. I became fearful, anticipating a life of frustration. I wanted to give up my recently acquired bad habits, but what could replace them that would actually satisfy me?

Although my friends considered me overly philosophical, I saw myself as simply trying to make sense out of life. Any goal appeared to be a dead end, so I began to question: “Is anything absolute? I have one opinion, someone else has another opinion, and someone else has another opinion. But what is the answer?” Certainly microbiology class or lectures in the autopsy lab weren’t providing answers to such questions. I was already disillusioned with my religious training. Where would I find answers to my questions?

I say I had rejected religion, but I had good reasons. My parents weren’t living up to the principles they professed and had tried to instill in me. They didn’t seem convinced, and I wasn’t convinced. They had sent me to an Orthodox Hebrew school, but that had only increased my disillusionment. Even my teachers hadn’t seemed to understand the essence of the Old Testament and the Torah, and the synagogues were more populated for Tuesday night bingo than for Saturday morning Sabbath services.

When I began to see Hare Krsna devotees on the Cornell campus, I was curious. I think I must have admired them right from the beginning, if for no other reason than that they were always there—day after day for several hours a day. They obviously had conviction, and it made me want to return to religion for the answers to my questions. I would see the men dressed in dhotis, their foreheads marked with tilaka, their heads shaved except for a sikha in the back. Usually I would be on my way to the student union building, and I would pull my hat down low and cross the street, I was miserable and bored, sunk in thoughts of my unanswered questions. I figured I didn’t have anything in common with these Hare Krsna devotees, but I did begin to think that maybe religion could answer my questions. Thus it was a considerable breakthrough when I decided to again experiment with religious life.

I visited various churches, temples, yoga groups, and meditation centers. A Quaker group near the campus would hold silent meditations, and I went several times. They would sit quietly for hours, and anyone who wanted to say something could stand up and speak. But it seemed mostly mundane. Someone would quote a poet or talk about the Grateful Dead or discuss what band was going to play on campus or speak on some other topic I had already rejected as not providing any ultimate answers. But I continued to search. I became especially interested in yoga, and I decided to become a vegetarian. I learned of so many religious people who were vegetarians, and I began to conclude that eating flesh would deter me from my spiritual goals.

I found a vegetarian restaurant about forty-five minutes from Cornell in the town of Trumansburg, and I used to go there regularly. The girl who owned the restaurant was interested in the Hare Krsna movement, and she would let Hare Krsna devotees from the Buffalo center stay there on occasion. Then one evening I was sitting in the restaurant when devotees entered, chanting Hare Krsna and putting sticks of incense at all the tables. Some of the devotees were selling books. The devotees’ happy, smiling faces, their enthusiasm, and their music all attracted me deeply. Suddenly I felt that I’d like to be a part of this group. I let the idea pass, but I purchased a set of three Krsna books from one of the devotees. I looked at the pictures, glanced at some of the Sanskrit words, which I couldn’t read, and wondered about the bluish boy with the flute in His hand and the peacock feather on His head. I gave the books to a friend.

But I decided I should become more seriously involved with yoga. I was already interested in a popular yoga group, and now I began regularly attending the chanting and meditation sessions. The members would chant their mantras softly, indoors. I asked, “If this is the Absolute Truth, like you say, why don’t you go out and chant in the streets like the Hare Krsnas?”

They said, “Oh, we don’t want to upset people. Everyone has his own path toward self-realization.”

I was again sensing hypocrisy, especially when I found that some of the members were involved in drinking and homosexual activities, but I continued attending the meditations. I even received initiation, but I found the philosophy of the group vague and impersonal. I was praying earnestly—to whom I wasn’t sure—for some guidance, and an answer came during a group meditation. It was as if a voice from within overwhelmed me: “Find a bona fide guru.” I didn’t know what the “voice” meant, and I wasn’t sure how to follow the instruction, but I never forgot it.

Then, after two years of study at Cornell, I took a leave of absence and turned toward the field of horsemanship. I studied under a top British instructor at an academy in Maryland, but I ran into the same frustrations I had met at Cornell: unanswered questions. I would be riding frisky thoroughbreds during the cold winter weather, and as we would approach the six-foot-high jumps, all I could think would be, “What if the horse falls on me? What if I died at this instant? What would I have attained?” I started to pray daily in complete despair, “O God, if there is a God, please take all these things away from me, and let me know what You want me to do!”

I called the telephone information for the number of the Washington, D.C., center of the yoga society I had joined at Cornell. The operator, however, instead of giving me the number, told me, “Don’t bother with them. They won’t accept an out-of-town member. Try the Hare Krsna center. They’ll accept anyone.” But I insisted, got the number, called, and was refused. I still didn’t call the Hare Krsna center.

By now, the prospect of a career in horsemanship also lost its taste, and I went to my parents’ home in New York City. I was unsure of what to do with my life. But I had to do something, so I got a job as a riding instructor. Then one day, in the Port Authority Bus Terminal, a devotee gave me a BACK TO GODHEAD magazine. I had been teaching riding in New York City for a few months and was becoming more and more frustrated. But the more I felt frustrated, the more I read and reread the BACK TO GODHEAD. The cover picture showed two men, like puppets on strings, being manipulated by the three modes of material nature. I felt that I could relate to that, as I could see that I was not in control of the events in my life. There was a full-page picture of the New Vrindaban farm community in West Virginia, and an article about chanting the Hare Krsna mantra on beads. I called the temple in Brooklyn, and the devotee I spoke with (Sravaniya-devi dasi) answered all the questions I had been asking for almost three years.

Sravaniya sympathized with my frustration and explained to me about transmigration of the soul. She told me, “We attain different bodies—animal, human, plant, male, female, and so on—according to our activities and desires. But only in the human body can we question the goal of life and realize that we are suffering. The goal of life is to learn to love Krsna.”

“In the BACK TO GODHEAD magazine,” I said, “I read about how the three modes of material nature control all that we do. But I read in the Bhagavad-gita where Krsna says, ‘Rise above the three modes.’ So how do we rise above the modes if everything we do is controlled by them?”

Sravaniya explained that devotional service to Lord Krsna, beginning with hearing about Krsna from a pure devotee, was transcendental to material activities. “Later on in the Bhagavad-gita,” she said, “Krsna says, ‘One who engages in full devotional service transcends the modes of material nature and comes to the spiritual platform.’ So you can rise above the modes of material nature by performing pure devotional service to the master of the modes of nature, Lord Krsna. But the key is that devotional service must be done under the guidance of a spiritual master. You have to accept a bona fide guru.”

Here was the clinching line. “Find a bona fide guru.” I was very relieved and pleased by the answers I was getting, but I had other questions. By the time we were finished, I was almost crying in joy. Sravaniya had given me tangible hope that the answers to all my questions lay in performing devotional service to Krsna.

On my next day off from work I visited the temple. I arrived early enough in the morning to be able to take part in chanting japa, attending the Srimad-Bhagavatam class, and eating prasadam. I went out with a group of devotees to chant Hare Krsna on the streets of Manhattan. It was wonderful. And I realized I had been sent there by the same person who, a year and a half before, had told me from within my heart, “Find yourself a bona fide guru.” I felt alive.

In my talks with devotees at the temple, I expressed my concern about making an abrupt change in my way of life. The devotees rose very early in the morning and were very disciplined in their practices. I knew it was the correct way to lead my life, but I also knew it was going to be difficult. The devotees agreed with me. But they pointed out that to achieve any goal in life I would have to work and perform austerities, and I now was striving for the supreme goal. I had been ready to undergo austerities to attain a doctorate in veterinary medicine, but this degree was even better, because you could take it with you after death.

The next day, when I returned to work, all I had to do was exercise a horse belonging to a big New York lawyer. I rode the bridle paths all day in Central Park, dressed in my custom-made breeches, boots, hunt cap, and jacket. But today I chanted the Hare Krsna mantra—Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare—as loudly as I could.

Within a few days, I moved into the Brooklyn temple, and the welcome I received from the devotees was wonderful. I could understand that Krsna was personally taking care of my life. He had directed me to His devotees, who could, by their words and sincere examples, help me to attain eternal knowledge and happiness. I received initiation from a bona fide guru, Srila Prabhupada, a few months later, and by following his sublime instructions, I am guaranteed to attain the highest goal available for any living being—eternal devotional service to the Supreme Personality of Godhead, Lord Krsna.

Leave a Reply