by Kundali dasa

The Sanskrit word karma is now at home in the English language. It’s in the dictionary, and most of us are familiar with it. But what does it mean? In many cases people have only a vague idea. Whenever I’ve seen karma discussed in print, the explanations have usually distorted the original meaning of the word as described by Lord Krsna in the Bhagavad-gita.

Karma (literally “action”) has four specific applications in the Bhagavad-gita: (1) work in general, (2) work for Krsna’s satisfaction, (3) work for personal gain, and (4) destiny. This last definition is the most commonly used today. It refers to the intricate sequence of actions and reactions in human affairs.

That our actions in the present help to determine our future, no one can deny. If a runner doesn’t train or if a student doesn’t study, we can hardly expect him to succeed. And we hardly expect a truly virtuous and pious man to go unrewarded or a sinner to go unpunished. This idea of karma was expressed by the modern poet John G. Whittier:

We shape ourselves the joy or fear

Of which the coming life is made,

And fill our future atmosphere

With sunshine or with shade.

The tissues of the life to be

We weave with colors all our own,

And in the field of destiny

We reap as we have sown.

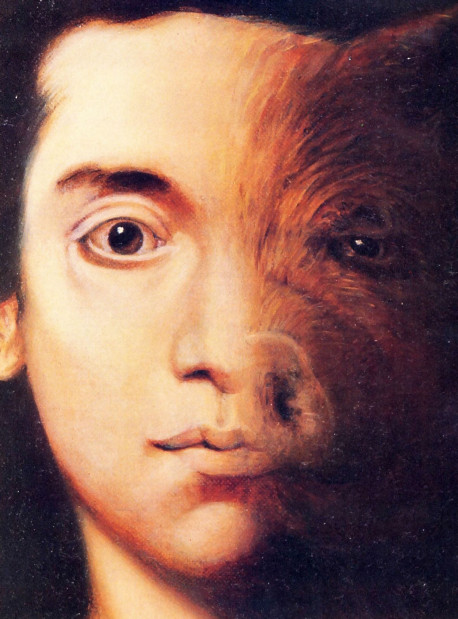

The idea that “we reap as we have sown” is very general, and one may question just how far the principle applies. For example, I’ve met persons who accept the principle of karma, but who stridently object. to the idea conveyed on the opposite page—a man becoming a pig because of his past karma. That’s going too far, they say.

But karma is not dependent on whether we choose to accept it or to reject it. It’s not under our control, something we can have made to order. It’s a law of nature, just like the law of gravity. And to change its workings is completely beyond us. We can ignore it, we can try to defy it, but we can’t change it.

According to the Bhagavad-gita, taking birth as a hog or any other animal is not at all difficult. Our thoughts, our desires, our actions all go toward determining our next birth. All a person has to do is make sure to nurture the consciousness of a hog, and in the next life . . . presto!

In the fifteenth chapter of the Bhagavad-gita, Krsna tells how the pure spirit soul, while covered by a material body, gets carried by his different conceptions of life from one body to another, just as the air carries aromas. When air wafts over a rose garden, it carries the fragrance of roses. When the same air passes over a cesspool, it carries foul smells. Similarly, when a conditioned soul gives up his present body at death, he carries his material conceptions from this life into the next.

Being forgetful of his factual identity, a conditioned soul strongly identifies with his material body, whatever it may be, taking it to be his true self. In actuality, his material body is only a combination of lifeless material elements activated by the presence of the spirit soul. But because the body is out-fitted with sense organs, the bewildered soul, who by nature wants to enjoy, tries to find pleasure in material objects. When a soul reaches the human platform, the quest for material pleasure drives him to perform varieties of pious and sinful acts, which mold his mentality in a certain way. That determines the gender and species of body he’ll deserve in his next life.

The living entity, thus taking another gross body, obtains a certain type of ear, eye, tongue, nose, and sense of touch, which are grouped around the mind. He thus enjoys a particular set of sense objects. (Bg. 15.19)

As the above verse indicates (and as anyone can see), the standard of enjoyment is different for different species. Take hogs. They don’t crave salads, pastries, and sweetmeats. They can’t appreciate the scent and feel of clean linen. They don’t yearn to see the Russian ballet or to hear Bach and Mozart. Humans, on the other hand, can’t appreciate the fouler things in life: rolling in the mud and filth, eating feces and other refuse, indulging in indiscriminate sex, even with parents and siblings. We are disgusted by the hog’s standard of enjoyment.

Nevertheless, if, by our actions and desires, we cultivate a piglike mentality, we can take a hog’s birth next life. Such a birth comes both as the ultimate outcome of our animalistic desires and as the just punishment for our sins.

There are, however, exceptions to the law of karma. Transcendentalists, or yogis who follow the path of pure devotional service to God, are exempted from its influence. Lord Krsna describes them in the Bhagavad-gita:

After attaining Me, the great souls, who are yogis in devotion, never return to this temporary world, which is full of miseries, because they have attained the highest perfection. (Bg. 8.15)

Devotees of Lord Krsna, “yogis in devotion,” are not under the influence of the law of karma, because they perform Krsna-karma. Rather than working for their personal aggrandizement and sense pleasure, they work with the sole aim of pleasing Krsna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead, Krsna-karma is the best type of action, because it purifies the consciousness of the conditioned soul. Thus one gradually becomes free from ignorance and from entanglement in the otherwise endless chain of karmic reactions.

The simplest way to immediately and continually engage in krsna-karma is to chant the Hare Krsna mantra: Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. These names of God, like God Himself, are transcendental and absolute. Chanting them does not produce karmic reaction. Sincere chanting gradually dismantles the illusion built up around the embodied soul, and he comes to realize directly his eternal, spiritual relationship with the Personality of Godhead. A sincere and dutiful chanter ultimately develops his dormant love for God and returns to Lord Krsna’s spiritual abode, where the law of karma has no influence. There everyone spontaneously serves Krsna out of pure love for Him, without any other motive. Attainment of this perfection through krsna-karma is the only guarantee that one will never go to the hogs in a future life.

Leave a Reply