Exeter, Harvard, SDS, drugs, Skinner, James,

and a place on the bay in Maine. Then what?

by Mathuresa Dasa

I first heard the chanting of Hare Krsna in 1968, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, during my freshman year at Harvard University. My dormitory room overlooked the sidewalk in Harvard Square where the devotees chanted in the afternoon several days a week. I liked the chanting, although it sometimes drew me away from my studies.

Having just spent four disappointing years at the Exeter Academy, in New Hampshire, I was enjoying a new freedom at Harvard. I could choose my own courses, make new friends, and take part in Boston’s collegiate youth culture. Since my father was then principal of Exeter, the move to Cambridge meant a new freedom from my family as well. As I walked back and forth to my classes through leaf-strewn Harvard Yard, ate with my classmates in the freshman dining hall, and studied diligently in Widener Library, I felt that now, at last, my real education was under way.

But Harvard, too, was a disappointment. As I studied I became more and more dissatisfied, although I couldn’t understand why. My friends, and even a few of my professors, admitted to some of the same feelings. I continued my studies anyway, for the sake of that prestigious degree, but the dissatisfaction increased, and I used to gather with my friends, smoke marijuana, and talk about the uselessness of education.

I was majoring in psychology because I wanted to better understand who I was and how the people of the world could live together happily and peacefully. Full of freshman enthusiasm, I signed up for some advanced courses, hoping to get right to the heart of my new field.

One course dealt mainly with the research of B. F. Skinner, the pioneer in behavioral psychology (and a member of the Harvard faculty). Skinner, I discovered, had spent a great deal of time in his Cambridge laboratory minutely studying the behavior of caged animals, especially Harvard Yard’s native pigeons. Although I admired his careful research, his chilling theories of how to manipulate human behavior seemed to leave no room for freedom—something I was just beginning to appreciate greatly.

In another course I read Principles of Psychology, by William James, the outstanding American psychologist and philosopher of the last century. Like Skinner, James had taught at Harvard. He had done much research on frogs, which had apparently abounded on the Harvard campus in the 1800’s, when the Charles River had been less polluted. James was a powerful thinker, but he also didn’t give me what I was looking for: practical ideas I could immediately apply to improve my life and the world around me.

I began to doubt the value of my studies. In a light moment with my roommates one evening, I concluded that the only substantial difference between James and Skinner was that James had studied frogs and that Skinner, because of a shift in the local fauna, had studied pigeons.

By this time the Vietnam War was at its height. I was adamantly opposed to it, and I started to get involved in radical politics. In the spring of 1969 members of the Students for a Democratic Society entered the administration building in Harvard Yard, threw out the dean and other faculty members, and declared that they would occupy the building until the military’s Reserve Officers Training Corps left campus. Though I wasn’t a member of SDS or much of a radical, I joined the demonstration. At least it was a change from the dull routine of classes.

The next day, just before dawn, a hundred state policemen surrounded the building. They were all big men wielding long black nightsticks and dressed in knee-high leather boots, leather jackets, and blue helmets with tinted visors that hid their eyes. After spraying tear gas through the windows, they broke down the doors and charged into the ad building.

We all decided to be non-violent, of course. So about sixty of us were loaded into paddy wagons, taken to the Cambridge police station, and booked on charges of criminal trespassing.

Meanwhile the Harvard student community, having witnessed the bust, went on strike and refused to attend classes. All these events got wide coverage in the Boston papers, and the story even made the cover of Life.

But after the initial excitement wore off, I began to lose interest in radical politics. The SDS meetings during the strike were disorganized and beset by endless petty quarrels. But the worst part of these meetings was the series of long-winded harangues by the leaders, in which they presented their hodgepodge of political ideologies. My studies seemed fascinating by comparison.

I don’t know if ROTC ever left campus, but I do remember that Harvard canceled final exams that spring. Now that was a victory we could all appreciate.

The next fall, after I helped organize a peace march in Washington, D.C., political activism joined my academic studies on the garbage heap of what I considered useless wastes of time.

A year later, after two years at Harvard, I took a one-year leave of absence, rented an apartment in the Jamaica Plains section of Boston, and began to study on my own. I felt a little relief. Free from the oppressive routine at Harvard, I did the best I could to stop using marijuana and other drugs. Then, late in March of 1971, as I walked down Tremont Street alongside the Boston Commons, a young woman walked up to me and handed me a magazine. Various political, religious, and cultural groups were always passing out literature on the Commons, so I took the magazine and kept walking, leafing through the pages. But after a moment I heard the young woman call to me from behind: “Sir, we just ask that you give a small donation to cover printing costs.” I was a little annoyed, and I thought of giving the magazine back to her. But instead my hand somehow went into my pocket, and I gave her fifty cents.

It was a BACK TO GODHEAD magazine. On the cover was a color photo of the Hare Krsna devotees chanting and dancing on the corner of the Boston Commons near the Park Street subway station. There were about twenty of them, young men and women, dancing in step with their hands raised above their heads. They wore bright orange and yellow robes, and every one of them was smiling with a jubilance I had never seen before.

During my freshman year at Harvard two years earlier, when I would hear the devotees chanting Hare Krsna and playing their instruments outside my dormitory window, I had never thought of approaching them and asking them what they were doing. I had still thought that my Harvard education had something meaningful to teach me. And besides, the devotees looked strange with their shaved heads and saffron robes. Whenever I had to walk through Harvard Square, I would cross the street to avoid them.

Now, however, I was beginning to understand that professors, radical leaders, family, and friends had nothing substantial or lasting to offer me. Nor, for that matter, did I have much of anything to offer them. So I became a little more curious to find out about the Hare Krsna devotees.

I knew they weren’t attending school or college, although they weren’t uneducated or illiterate, either (the BACK TO GODHEAD in my hands testified to that). And I knew they didn’t take drugs or smoke cigarettes. What were they all about, anyway?

I went back to my apartment and read the BACK TO GODHEAD, beginning with the lead article, by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Srila Prabhupada explained that to become disgusted with materialistic life is not enough. One has to find a positive alternative. He compared materialistic life to a glass full of ink, and renunciation of materialistic life to pouring the ink out of the glass. But, he continued, a glass is meant to be filled with something. So if you reject materialistic life but don’t replace it with spiritual life, the ink of materialistic life will fill your glass again.

This analogy struck home. I had personally experienced that although I had rejected my home, family, education, and friends, I was still relying on them, for want of anything better. I would still sometimes use drugs and do all the things I already knew wouldn’t make me or anyone else happy. Srila Prabhupada explained that we had to fill our lives with the chanting of the holy names of the Lord, Krsna, and with other devotional services to Him. This was like filling up the glass with milk. If our glass was filled with the milk of Krsna consciousness, we would no longer be attracted to the ink of materialistic life.

I was startled at how perfectly Srila Prabhupada had analyzed my problem. In contrast to my former schoolmates, who thought I was being too negative, and to my parents, who suggested I see a psychiatrist, Srila Prabhupada seemed to know me better than I knew myself. Accepting him at once as my friend and guide, I decided to visit the Boston Hare Krsna center to find out some more about Krsna consciousness.

I found the address in my BACK TO GODHEAD and located the temple on a map of Boston. It was a couple of miles across town from my apartment. Lacking money for a bus or cab, I set out on foot.

The walk took me through a section of Boston I had never explored before. The crosstown street I walked along (Harvard Street, ironically enough) was lined with shops, delicatessens, banks, grocery stores, movie theaters, and neat two- and three-story houses. A wooden sign hanging over the sidewalk on one of the many side streets marked the house where President Kennedy was born. Normally, the shops and theaters would have interested me, what to speak of Kennedy’s birth-site—that certainly would have caught my attention, at least as a curiosity. But on that day the little Kennedy house seemed like an insignificant island in the middle of nowhere, and the shops, although busy with customers, appeared empty and unreal. They were real enough, of course, but pale and lonely in contrast to my heart’s desire to find out more about Krsna consciousness. Harvard Street and JFK were just so much of that same ink.

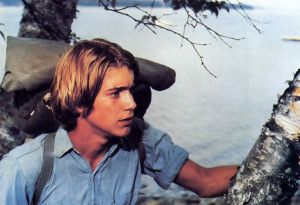

At last I arrived at the Hare Krsna temple, a large three-story house on North Beacon Street. I must have been quite a sight in my old bluejeans and work shirt. My hair was long and unkempt, and I had become skinny and pale from irregular eating and occasional bouts with drugs and alcohol. I rang the doorbell.

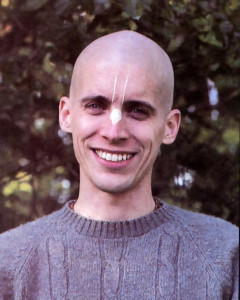

A devotee opened the door part way, stuck his clean-shaven head out, and said, “Yes?”

“I want to know more about what you’re doing,” I said.

He smiled and asked me to come in. Leaving my shoes on a shelf by the door, I stepped into the front hall.

The aroma of incense, mixed with the fragrance of fresh flowers and exotic smells from the kitchen, completely captivated me. The temple was so clean, the floors were so well-polished, and the walls and ceilings so brightly painted that I was astonished.

My host told me that the temple housed a printing press and an art studio and that the devotees were busy publishing books on the science of Krsna consciousness written by their spiritual master, Srila Prabhupada. Some devotees, he said, painted illustrations for the books and magazines, some operated the press, some cleaned the temple and cooked, some sold the books and did business, and everyone (including the couples with children) rose at four in the morning and chanted Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. He told me the chanting meant, “O my dear Lord Krsna, please let me serve You.”

I could see that the devotees weren’t inactive and discouraged like me but always active in Krsna’s service. As we talked, my host had a comfortable chair brought for me, while he sat on the floor, friendly and confident. Everything about him was fresh, clean, and personal.

After half an hour or so he told me that he had a lot of work to do, so I took my leave and promised to return for the festival and feast next Sunday afternoon.

I attended one or two Sunday feasts that spring, and I began to chant Hare Krsna regularly on my own. By chanting Hare Krsna and eating krsna-prasadam (food offered to Krsna) with the devotees, I became attracted to the life of devotional service. The devotees explained that Krsna was a name for God and that by chanting His name we directly associate with Him. They were always quoting their spiritual master and the Bhagavad-gita. I didn’t understand much of the philosophy at first, but the prasadam was so delicious that, on the devotees’ advice, I stopped eating meat, fish, and eggs.

During one of my visits to the temple, I asked for a copy of Srila Prabhupada’s Bhagavad-gita As It Is. They were out of stock. So the next day I looked all over town and found a copy in a Copley Square bookstore. It was a paperback published by Macmillan, with introductions by Thomas Merton and Allen Ginsberg and explanations of the text by Srila Prabhupada. I had already read two or three other Gitas, with little understanding. But from reading BACK TO GODHEAD I had become certain that Srila Prabhupada’s commentaries would be clear and relevant. Later in the spring, when an old friend invited me and several others to stay with him on his parents’ land in Maine, I took Bhagavad-gita As It Is with me.

The property in Maine was four acres on a hill overlooking a coastal bay. It was peaceful and scenic—an ideal setting, I thought—but after a few days I discovered that I missed the cheerful devotees. My friends and I decided to cook only vegetarian meals, and I even introduced them to the chanting of Hare Krsna. But they also smoked marijuana, and out of habit I would join them. And on weekends my friend’s parents would drive up from Massachusetts and cook a big Sunday dinner with barbecued meat, boiled lobster, and steamed clams. Despite the ideal country setting, I realized that I just wanted to be with the devotees.

Every day I would sit and read Srila Prabhupada’s Bhagavad-gita As It Is, and one day a verse in the second chapter particularly caught my attention: “That which pervades the entire body you should know to be eternal. No one is able to destroy that imperishable soul.”

In the purport, Srila Prabhupada explained that what pervades our bodies is consciousness. Pinch yourself anywhere and it hurts. Most people assume that since the body is temporary the consciousness spread throughout the body is also temporary. But in this verse Lord Krsna states that, unlike the body, consciousness is eternal: it has no beginning and no end. The body is born and dies, but the soul, the spiritual self that is the source of consciousness, has no birth and death.

Just theoretically understanding this verse made me very happy. Krsna and Srila Prabhupada were saying that we are eternal, and I had no reason to disbelieve it, no evidence to disprove it. This, not the study of caged animals and disturbed people, was the key to psychology—to real satisfaction. We are eternal, and therefore we can never be happy by trying to adjust our temporary surroundings.

It further occurred to me that this understanding of our eternal nature was part of what made the devotees so energetic and happy. They must have more than just theoretical understanding, I thought. They must have directly experienced that they are eternal and practically realized their eternal relationship with Krsna. There was no other way to account for their profound joyfulness, their friendliness, and other qualities I noticed in them. Srila Prabhupada’s presentation of the Bhagavad-gita, combined with my association with his disciples, was having a deep effect on my life. I wanted to begin my spiritual education—to join the devotees and be like them.

I started regularly going off alone to some nearby woods to practice the chanting and dancing I had seen the devotees do. I thought I should become expert at this so I could show the devotees I was qualified to be a member of the temple.

When I finally decided to return to Boston and become a full-time devotee of Krsna, I didn’t think I would be able to explain this decision to my friends. So I left early one morning without letting anyone know. It took me all day to hitchhike down to Boston, and during the last leg of the trip it rained. I arrived at the temple’ about nine in the evening, soaking wet.

Standing in the front hall, dripping, I surprised a devotee with the news that I wanted to join. He ran to get me a towel and a plate of prasadam. I dried off and ate while he explained that he was about to lock up for the night and that I should come back the next day and talk to the temple president. I was disappointed, but I understood that it was late and that most of the devotees were already asleep.

So I walked across town to spend one last night in my apartment. As I walked I chanted Hare Krsna and looked forward to joining the temple the next day.

Leave a Reply