There’s More to It Than Stubbing Your Toe

By Jayadvaita Swami

In most people’s minds a person is a body. Whenever a child is born, a new person has come into existence. He grows up, lives out his life, and finally dies, and then that particular person has ceased to exist. In this view, life is sort of a one-time, open-and-shut affair.

In most people’s minds a person is a body. Whenever a child is born, a new person has come into existence. He grows up, lives out his life, and finally dies, and then that particular person has ceased to exist. In this view, life is sort of a one-time, open-and-shut affair.

From the Vedic viewpoint, however, a person is an eternal traveler who wanders from one body to the next. He appears in different guises—sometimes as a genius, sometimes a fool, sometimes a wealthy man, sometimes a pauper. Sometimes he assumes the role of an American or Englishman, at other times an Indian or Chinese. And with each change of body, he forgets his previous life.

Now one might ask, what is it that determines the kind of body one will appear in next?

According to Bhagavad-gita, our next destination depends upon the direction our consciousness points to at the time of death; it is our consciousness that carries us to our next body. And the direction our consciousness points to will naturally depend upon the activities we have performed throughout our life.

To give an analogy: A student enters high school and pursues his studies for some years, then graduates and goes on either to college or to some sort of work. Now, what kind of job or college he goes to will depend to a great extent on how he has spent his time in high school. If he has studied diligently and done well on his exams, perhaps he will go on to an excellent college and a rewarding career. On the other hand, if he has frittered away his time, he may find himself struggling to land a tiresome job for low pay. In other words, his next life—his life after school—depends on how he thinks and acts before he graduates.

In the same way, our next body will depend on how we think and act now. We have only so many years in our present body, and then the examination comes, at death. At death our consciousness is tested. We have spent our time however we felt best, and at death “Time’s up!” Our present lifetime comes to a close, and our consciousness carries us to our next body.

It is not desire alone that determines our next body; we get not exactly what we desire but what we deserve. A student may desire to go to Harvard or Yale, but his desire alone will not get him in; he must also have high enough grades, be able to pay the tuition, and so on. Similarly, it is not that we will become wealthy and aristocratic in our next birth merely by aspiring to wealth and aristocracy now. We must first act in such a way that we deserve it.

So people are born in different countries, different families, and’ different bodies not by chance but according to precise and intricate natural laws of cause and effect. These laws are known in Sanskrit as the laws of karma.

So people are born in different countries, different families, and’ different bodies not by chance but according to precise and intricate natural laws of cause and effect. These laws are known in Sanskrit as the laws of karma.

The word karma literally means “action,” yet it also carries the import of “fate” or “destiny.” This is entirely reasonable, for it is our actions that determine our fate. This is not a matter of esoteric belief or superstition but of common sense and practical everyday experience. Suppose I put my hand in a fire. This is a kind of action. Yet it also implies an entirely predictable reaction—I’m going to get burned.

So in everyday life my actions have certain reactions; cause and effect are always at work. I may not always understand what the results of my actions will be, and when something has taken place I may not always understand why—but at least I can be sure that what is happening now has resulted from what has gone before and will influence what will happen next.

Now, the Vedic teachings carry this understanding one step further. From a materialistic viewpoint, cause and effect may bounce me around during my lifetime in this body, but no longer—when the body is dead, I am dead, and the chain of action and reaction comes to an end. But what the Vedic teachings propose is that this chain of action and reaction extends not only within our present lifetime but before it and beyond it, throughout a succession of lives. Why does a person take his birth in a particular body? It is because of his past karma, his past activities. What kind of body will he be born in next? Again, that depends on his karma. His present activities—together with the sum total of his previous activities—will determine his consciousness at the time of his death, and that consciousness will carry him on to his next body.

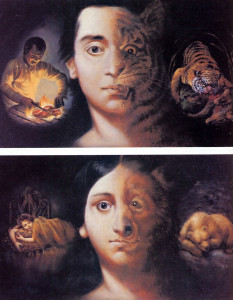

What’s more, a living being may travel not only from one human body to another but also down from the human species to the body of a plant or animal. In these lower species also, birth and death take place—consciousness enters the body, stays there for some time, and then leaves for the next body.

So the soul travels from one body to the next, and from one species to the next. Sometimes he goes up to the human form of life, sometimes down to the plant or animal kingdom.

In the material world, all living beings have the same spiritual nature, yet think and act differently according to the different material bodies they have received. A living being with a cat body thinks and acts like a cat, with a fish body he thinks and acts like a fish, and so on. By nature’s laws, he has no freedom to do otherwise. So by nature’s laws the living beings in the lower species always progress from one species to the next one higher, until they gradually reach the human form. After all, since plants and animals have virtually no freedom, they never do anything contrary to nature’s laws. A tiger may eat flesh, for example, because that is the tiger’s nature; but a tiger will never steal oranges.

In human life, however, we can transgress the laws of nature. The human body offers us freedom, and we may use this freedom properly or improperly, as we choose.

By nature’s laws the human body is specifically meant for spiritual realization. In lower forms of life we can eat, sleep, have sex, and defend ourselves, and of course we may perform the same activities in the human body also. But in the human body we also have the intelligence to understand who we are and what the purpose of life is, who God is and how we can develop our love for God. This is the real purpose of human life.

The animals also have intelligence, but they can use their intelligence only for eating, sleeping, mating, and defending. If the human being uses his intelligence only for these purposes, he is misusing the advantages of his human life. This misuse is what is known as “bad karma.”

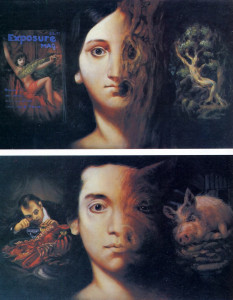

Most of us have heard or used the phrase “bad karma,” usually in relation to trifles—if we get a parking ticket or stub our toe or lose a coin in a vending machine, we write it off as “bad karma.” Yet bad karma can be far more serious, as the illustrations on these pages point out.

The girl on the cover of Exposure may think herself lucky to have won a choice modeling assignment, but she is unaware of the karmic reactions involved. Although human life is meant for higher purposes than showing off one’s body, there are other forms of life—the tree, for example—in which standing naked is entirely natural. So the girl is unwittingly molding her actions and consciousness in such a way that her next body may be that of a tree. And after a long lifetime in the body of a tree, the soul must then transmigrate upward through millions of more species before again getting the opportunity of a human birth.

Sometimes we say that someone eats like a pig or sleeps like a bear. Here again, the laws of karma act with a kind of poetic justice. For if someone wants to eat like a pig, why should he take his next birth in a human body? Pig consciousness, pig body. This is the law of nature.

Leave a Reply