A Political Activist becomes a monk in

the Hare Krsna Movement

by Melvin R. McCray

Reprinted with permission from The Princeton Alumni Weekly

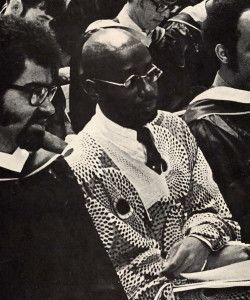

I saw John Favors for the first time in the fall of 1970, at the introductory meeting of Princeton’s Association of Black Collegians. As ABC’s president, he delivered an impassioned speech on the role of blacks at Princeton. Though only five feet nine inches, he was an imposing figure in his leopard-print dashiki and matching fez-like hat, with walking stick, pipe, bushy afro, and full beard. At that time he called himself Toshombe Abdul, and he spoke with the force and dynamism of Malcolm X.

Favors reminded us that we were products of the black community and argued that blacks were now being admitted to Ivy League universities mainly because of the demonstrations and riots of the ’60s. He insisted that those struggles gave us a responsibility to return to the community and help rebuild it. His audience of 200 black students, mostly freshmen, was enthralled by his charismatic delivery and filled McCosh 30 with thunderous applause.

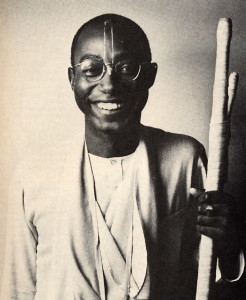

I barely recognized Favors when I ran into him nine years later at a vegetarian restaurant in New York City. His face and scalp were cleanshaven and he was dressed in an orange robelike garment. He held a cloth pouch in one hand and a long cloth-covered staff in the other. Much to my surprise, John Favors, alias Toshombe Abdul, had become Bhaktitirtha Swami of the Hare Krishna movement. He had set aside the politics of the revolution and adopted the life of a monk in what is formally known as the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON).

My curiosity aroused, I questioned him at length about this metamorphosis. My first impression was of a man who had swung from one tangent to the other with no consistency of purpose, his joining the Hare Krishnas being just the latest in a series of dramatic personality changes. But as our conversation progressed, I realized that this was not the case. There was, in fact, an inner constancy that guided his transition from revolutionary to spiritualist. His was a story of evolution rather than abrupt transformation.

Favors was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in February 1950, the youngest of six children in what he describes as an impoverished but deeply religious family. The combination prompted him to adopt “a very humanitarian, socialisitic posture.” As a teen-ager he was active in local politics. He tutored in neighborhood centers, and at the age of 14 he became president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s midwest student division.

After graduating from Cleveland’s East Technical High School, Favors received a scholarship to attend the Hawken Academy for an additional year of college preparation. By the time he arrived at Princeton in 1968, he had developed an enthusiasm for intellectual inquiry and a desire to improve the material circumstances of his fellow man in general and blacks in particular. “Because I had seen so much poverty,” he says, “I was interested in doing something for myself and others.”

During the turbulent late ’60s and early ’70s, Princeton saw its share of civil disobedience. In the spring of 1969, a coalition of students barricaded themselves in the New South building to protest the university’s investments in South Africa. A year later students clashed with local police while demonstrating at the Institute for Defense Analysis. In the fall of 1970, black students occupied Firestone Library to press their demand for a Third World Center. During the early years of the new decade, Stokely Carmichael, Angela Davis, Dick Gregory, and Huey Newton all addressed large audiences at Princeton.

Favors joined the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, the Black Panther Party, and other activist groups. He developed an ideology that stressed his African roots, and he began traveling extensively in black nationalist and socialist circles in the U.S. and abroad. It was during this time that he adopted the name Toshombe Abdul.

Eventually Favors became disenchanted with political activism, feeling that it was bringing little or no progress. “I traveled to a few other countries and saw how so many revolutionary leaders who had good intentions became exploitative once they got into power. Sometimes they were more exploitative than the previous regime. I saw racism and class struggles and started to realize that it’s not just one political paradigm versus another that is going to bring man equanimity, peace of mind, and a more just order.”

He concluded that other approaches must be tried to attack such seemingly unsolvable problems as the depletion of natural resources, the widening gap between rich and poor, the threat of nuclear war, and man’s inhumanity to man. “If you put a very exploitative man in a socialist environment,” Favors decided, “he’s still going to find some way to exploit. What we really need is for man to have a change of consciousness.” So Favors, a psychology major, began doing research on hypnosis, mental telepathy, clairvoyance, and dreams. He also studied the writings of Plato, Aristotle, Emerson, Thoreau, and Schopenhauer on sense perception, consciousness, and the nature of reality.

Favors turned next to Eastern religions, attracted by their emphasis on expansion of consciousness and purification of the senses as well as their ideal of service to God and man. He started reading the Vedas and the Bhagavad-gita, the scriptures of Hinduism, and was intrigued by what he calls their “scientific” approach to the mastery of life. He wondered if these mystical philosophies could succeed where political action had failed in bringing about a more just world order.

While still at Princeton, he undertook formal lessons with Sri Chinmoy, Swami Satchidananda, and other Indian gurus who related Hindu philosophy to the Western world. Favors continued his political activism at the same time that he began pursuing these spiritual inquiries: “I would leave a Black Panther rally or an ABC meeting and go to New York and study meditation for a couple of days with some swamis.”

The conflicting demands of his double life came to a head at graduation, in June 1972. He was awarded a scholarship to attend the University of Tanzania, where he could become more directly involved in third-world political and social activities. “But I wasn’t sure whether I really wanted to continue working in politics,” he says, “or whether I wanted to become more contemplative and introspective.” He put off this decision by taking a job in the office of New Jersey Public Defender Stanley Van Ness, where he worked on penal-reform projects, while also taking lessons in Vedic philosophy at the Hare Krishna temple in New York City. “It gave me a chance to scrutinize the different polarities in myself, the political and the spiritual.”

Favors believed that Hare Krishna devotees were following the original Vedic teachings more closely than any other sect, but he was not convinced yet that he wanted to commit himself to a totally spiritual life, nor was he sure the Hare Krishnas would be the right choice for him. “The first time I saw a Hare Krishna,” he says, “was up in Harvard Square at a football game. It was very cold, and a group of them were standing on the corner chanting. I looked at them and thought, ‘This is the epitome of absurdity.’ I presumed they were rich white students just out looking for some different kind of drug or alternate experience. But when I passed by again two hours later, they were still on the corner chanting in the cold. I knew then there was something extraordinary about them. Years later I was shocked to find that those people ringing cymbals and playing drums in the street possessed an intense philosophy about God.”

Though Favors was doing quite well financially, and felt his job directing prison programs was an important one, he still was dissatisfied. After working with Van Ness for a year he decided to leave. “He knew I was a little unusual,” Favors says, “because I would go to parties and never drink or eat meat. I told him that I was becoming a member of a religious organization, and that we had a school in Dallas where I was being called to do some teaching. It was an unusual situation. Just overnight I knew I had to leave. I knew at that point my whole life was going to change. I gave all my possessions away. I took a razor and shaved my head. The next morning I got on a plane and went to Dallas.”

Americans have come to know the Hare Krishnas by their street chanting, airport book-selling, and portrayal in the media as a religious cult. It is not generally known that they are an international organization with several thousand members and centers in many of the world’s major cities. Even less is known about their religious beliefs, based on the 5,000-year-old Vedas, which teach the worship of one supreme God and many of the same concepts presented in the Ten Commandments. The name Krishna means “all-attractive one,” and is used to describe the supreme qualities of God. The chant—”Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare”—is a prayer which means, “O Lord, please engage me in Your service.”

The religion of the Hare Krishnas is basically the same as the Hinduism practiced by 600 million Indians. The notable difference is that the Krishnas follow the Vedic interpretations of A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, who founded the Hare Krishna movement to spread Krishna consciousness to the English-speaking world. He arrived in America in 1965, at the age of 69, and began teaching that the Vedas specify the Hare Krishna mantra as the most effective method of spiritual realization in this age. The chant, therefore, is at the core of the sect’s religious practices. Not all followers of Vedic scriptures, however, give such prominence to this particular mantra over other Vedic chants.

The negative reaction of most Americans to this religious doctrine was understandable, given the country’s deep-rooted cultural biases against such beliefs, dress, and behavior. Many parents and the religious community as a whole remain alarmed at the proliferation of cultlike religious organizations that attract large numbers of young persons. Favor’s decision to join the Hare Krishnas was received with chagrin by most of his family, friends, and classmates.

At first he taught academic courses in the ISKCON school in Dallas. Later he was assigned to the organization’s Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, the largest publisher of books on Hindu philosophy and religion in the world. Its primary function is to print and distribute more than 70 volumes of translations of and commentaries on the Vedic scriptures by Swami Prabhupada. In fact, with over 60 million volumes distributed, ISKCON derives most of its income from the sale of these books.

For his first seven years in the organization, Favors undertook a rigorous study of Indian philosophy and Sanskrit literature. Meanwhile, he was moving up rapidly in the ISKCON hierarchy. “I was sort of taken under the wings of the leading swamis,” he says.

Then, in 1979, Favors became a sannyasi, which means renunciant, or monk. He’s one of two black swamis in the Vaishnava order and one of two dozen leaders directing the work of the Hare Krishna movement. At that time he was renamed Bhaktitirtha Swami, which means “one in whom others can take shelter.” Not all Hare Krishnas are encouraged to become monks; in fact, most marry and raise families. Even within the hierarchy, priesthood is a radical step. “I’ve been celibate for ten years,” he notes. “One may ask how it is that a young man who is at his prime, when sexual tendencies are very active, could take to such a lifestyle. But obviously enjoyment must be there. When you are developing a higher taste, then it becomes easy to give up something else.”

For the last four years he has been helping to direct ISKCON’s activities in Africa—especially in Kenya, Nigeria, Ghana, Zimbabwe, and Zambia. Favors has received enthusiastic support from the Africans he has met, which he attributes to his spiritual posture. “Once you are out of America,” he says, “there is a whole different mood of how a spiritualist is treated. In America people may say, ‘Look at this weird guy.’ But in Africa they know immediately that my dress indicates a very high priest. I can meet with ambassadors, chiefs, princes, and I can get funds just based on the programs and the posture that I represent.” Backing up his words is the fact that most of the land ISKCON operates on in Africa has been donated by government or private sources.

Some of Favors’s classmates might question the validity of spreading a religious philosophy from India among Africans. Why should Krishna consciousness be any more relevant than indigenous African religions or for that matter the Western religious doctrines which are taught there? According to Favors, the Vedic religion has been acceptable to the Africans he has encountered because of its similarity to their own. “To a certain extent, the principles we follow are not much different from what a spiritualist in Ghana or a person in the Yoruba tribe would follow: the same hierarchy, the same concepts of life after death, and the same knowledge of pyschic centers.

“Africans feel that Vedic teachings clarify beliefs they have long held. Our contribution is a scientific explanation of phenomena they have accepted for centuries without understanding. Rather than propose a change of culture, as the Christian missionaries did, Krishna consciousness suggests that people simply add an understanding of the scientific process of devotional service, as described in the Bhagavad-gita.”

Favors feels that African culture is being eroded by influences from the West, and the Vedic religious philosophy can strengthen native practices. “I am trying to get Africans to realize what great teachings they have—teachings that deal with man’s relationship to man in a very pure way. But Africa and all of the third world is becoming more and more Western in consciousness, so we are telling them, ‘Don’t take this materialism as a priority.”‘

Encouraged by the warm reception he has received in Africa, Favors is planning a number of major projects, including hospitals, more schools, and expanded food-distribution systems. He is actively recruiting people to run these programs from both inside and outside the Hare Krishna organization.

Looking back on his experience at Princeton, Favors says, “The educational experience I had was good in that it allowed you a certain amount of freedom and creative thinking. My experience at Princeton helped me to see that I didn’t want to be a materialist, but it was my education in the Hare Krishna movement that convinced me spiritual life is a meaningful, viable alternative not only for me—but for everyone.”

I am a christian willing to be a hare rama member.

My experience is much like Ramatirtha’s. I consider myself a Hari Krishna, Muslim, a Jew, a Christian and a Rastafari.

Although some sects of Hindus, Jews, Muslims and Christians might reject me, which I find quite acceptable and natural, all of these ideas come together in me and my life.

Jai ho Ramatitha Swami. Hari Krishna Prabhupada!