The Molding of the Hare Krsna Movement in British India

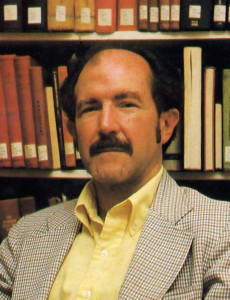

by Dr. Thomas J. Hopkins

Dr. Thomas J. Hopkins is the chairman of the Department of Religious Studies at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Dr. Hopkins, author of The Hindu Religious Tradition, has made his special areas of interest Hindu devotional movements, Puranic and popular Hinduism, Hindu temples and religious arts, the Bhagavad-gita and its interpretations, the Krsna consciousness movement, new religions in America, yoga meditation, and related fields. What follows is a lecture he delivered in February 1981 before the South Asia Seminar at the University of Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia.

Dr. Thomas J. Hopkins is the chairman of the Department of Religious Studies at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Dr. Hopkins, author of The Hindu Religious Tradition, has made his special areas of interest Hindu devotional movements, Puranic and popular Hinduism, Hindu temples and religious arts, the Bhagavad-gita and its interpretations, the Krsna consciousness movement, new religions in America, yoga meditation, and related fields. What follows is a lecture he delivered in February 1981 before the South Asia Seminar at the University of Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia.

Tremendous changes have taken place in American religious life in the past two decades. Some of these changes have been largely internal and continuous with the past history of American religion, such as the rise of the Jesus movement and the rapid growth of charismatic and evangelical Christian churches. At least one change, however, has no clear historic parallel: the upsurge of religious movements whose leaders and doctrines have roots in traditional Asian religions. Both east Asia and south Asia are well represented in this development, but by far the largest number of new groups have come from India—so much so that the phenomenon can almost be considered a missionary movement from India to America, a reversal of the Western missionary efforts of the 18th and 19th centuries. Instead of Westerners setting forth to Christianize the heathen, the “heathen” are coming to the West and are rapidly winning converts to their own religions.

Why has this happened? Many explanations have been put forth, most of them in terms of Western social and religious history: the decline of religious vitality in the West, disillusionment with Western technological culture, the alienation of young people from the political and religious establishment, and so on. All of these are undoubtedly important, but too little attention has been given to the other side: the surprising vitality of Asian religions in the face of at least two centuries of Western world dominance. A look at the Krsna consciousness movement may give us some insights into this side of the emerging pattern.

The success of the Krsna consciousness movement, if not unique, is certainly outstanding among the groups with Asian roots that have flourished in America in the last two decades. What are the factors that have made the Krsna consciousness movement so successful? To understand these factors, it’s necessary to understand where the movement came from in India. My primary thesis today is that the reasons for the success of the Krsna consciousness movement in the U.S. and elsewhere outside of India derive primarily from the development of that movement in India during the 19th century. What I want to start with today, therefore, is a little bit of the history of the 19th century, looking particularly at the disciplic line of the Krsna consciousness movement.

The development of the Krsna consciousness movement in the 19th century—or the Gaudiya Vaisnava movement, as it is known in India—occurred in the context of a much larger process of social and religious change, which is represented by a number of very notable figures. The first of these is Ram Mohan Roy, who is generally seen as the father of the Hindu renaissance in the 19th century. Ram Mohan Roy was by no means alone in this effort; change was taking place in many areas. After him many others were involved in social and religious change—many of them, interestingly enough, coming out of the religious background stemming from Sri Caitanya. *Ram Mohan Roy himself was not specifically a Caitanyite. Though his father was of that background, his mother was a worshipper of Durga, so even in his parentage he had a kind of mixed orientation. But other, later figures also had some relationship to the Caitanya community and its tradition, so that there was a rather unusual interaction going on in Bengal between the Caitanya tradition, the influence of the modern English language and other Westernization processes, and the renaissance of the Hindu tradition.

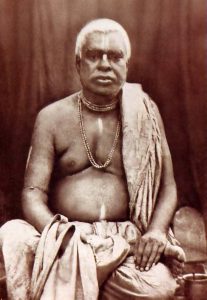

What I want to look at first is a prime example of this interaction in the person of Kedaranatha Datta, better known by his religious name of Bhaktivinoda Thakura. He, more than anyone else, put together the factors in the 19th century that made possible the development of the Gaudiya Vaisnava movement in Bengal and the Krsna consciousness movement in the Western world. Frankly, I didn’t know much about him before I started doing some research for this talk. The more I found out about him, though, the more fascinated I became. So I’d like to tell his story, because it seems to me he is not only outstanding in his own personal capability but is in many ways representative of what was going on in Bengal in that period.

Bhaktivinoda Thakura was born in 1838. He came out of a Caitanyite background, but rather characteristically for that time and place, he was headed in the direction of English and Western education. His father died when he was relatively young, but his mother’s family had money and he was brought up in a zamindar (A zamindar is a wealthy householder—Editor) household of some importance. He was sent to high school in Calcutta at the Hindu Charitable Institution and later completed his education in Calcutta at a Christian college. So he’s typical of that group in Bengal who had high social status, an intellectual orientation, and an English education that prepared them for life under British rule.

After finishing college Bhaktivinoda started teaching in Orissa, and he is credited by his biographers as one of the pioneers of English education in that state. But he didn’t stay in education for very long. Instead, he studied law, passed his law examinations, and in 1862 took employment as a civil servant with the government of Bengal. Then in 1866 he was appointed a magistrate within the provincial civil service, and he carried on in that service for the rest of his government career, until his retirement in 1894.

Bhaktivinoda Thakura was in many ways a typical educated Indian serving the British government in India. He held a variety of magistrate posts in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. He learned Persian and Urdu in Bihar, where the Mogul tradition was still preserved in legal and administrative circles, and in Orissa he was for a time, the British-appointed overseer of the Jagannatha temple in Puri; in each case his principal concern was to promote the cause of British law. As a competent and successful young magistrate, his interest in his own religious tradition was strictly personal and was largely a matter of cultural nostalgia. There is little evidence that he saw his Gaudiya Vaisnava heritage as a worthy rival to Christianity and the Western intellectual tradition, nor did he see his private religious interests as deserving of public attention. For the first thirty years of his life, in fact, he had little contact with the real religious and intellectual core of his own tradition. He was unable even to find a copy of the Caitanya-caritamrta, which was written in his native Bengali, and he had no acquaintance with either the Srimad-Bhagavatam or the writings of the Six Gosvamis of Vrndavana.

All of this changed in 1868, when he received from a friend a copy of both the Caitanya-caritamrta and the Srimad-Bhagavatam, or Bhagavata Purana, with the commentary of Sridhara Svami. He plunged into these works, discovered their wealth of religious teaching, and went through a personal transformation. For the first time he realized there was something in the Caitanyite tradition worth preserving-and not only worth preserving, but worth promoting on a public level. This he took as his new obligation.

I have a copy of a little pamphlet that Bhaktivinoda Thakura published called The Bhagavata: Its Philosophy, Ethics, and Theology. It was written soon after his great discovery and is based on perhaps the first public lecture he gave to announce his new-found cause. It is clearly directed to English-educated Indians who, like himself, had lost contact with their own tradition. Written in marvelously fluent English, it is nonetheless an argument against the inroads of British education and Western cultural values. It is not a total rejection of the West but a plea for reform based on the religious insights and teachings of Caitanya. In advocating reformation, Bhaktivinoda does what any successful reformer must do: he maintains contact with the current social and intellectual climate and yet carries his message beyond the existing level to a new synthesis. But rather than trying to describe this work further, I’d like to give you a sense of its flavor by reading excerpts from the first part of it.

“We love to read a book,” he writes, “which we’ve never read before. We’re anxious to gather whatever information is contained in it, and with such acquirement our curiousity stops. This mode of study prevails amongst a great number of readers, who are mere repositories of facts and statements made by other people. But this is not study. The student is to read the facts with a view to create, and not with the object of fruitless retention. Students, like satellites, should reflect whatever light they receive from authors and not imprison the facts and thoughts as the magistrates imprison the convicts in the jail!

“Thought is progressive. The author’s thoughts must have progress in the reader in the shape of correction or development. He is the best critic who can show the further development of an old thought, but a mere denouncer is the enemy of progress and consequently of Nature. . . . Thus the shallow critic and the fruitless reader are the two great enemies of progress. We must shun them. . . .

“The Bhagavat [that is, the Bhagavata Purana], like all religious works and philosophical performances and writings of great men, has suffered from the imprudent conduct of useless readers and stupid critics. The former have done so much injury to the work that they have surpassed the latter in their evil consequence. Men of brilliant thoughts have passed by the work in quest of truth and philosophy, but the prejudice which they imbibed from its useless readers and their conduct prevented them from making a candid investigation. .

“The Bhagavat has suffered alike from shallow critics both Indian and outlandish. [He knew English well enough, I think, to know what he was saying.] That book has been accursed and denounced by a great number of our young countrymen who have scarcely read its contents and pondered over the philosophy on which it is founded. It is owing mostly to their imbibing an unfounded prejudice against it when they were in school. . . . We are ourselves witness of the fact. When we were in college, reading the philosophical works of the West and exchanging thoughts with the thinkers of the day, we had a real hatred toward the Bhagavat. That great work looked like a repository of wicked and stupid ideas scarcely adapted to the 19th century, and we hated to hear any arguments in its favor. With us then a volume of Channinge Parker, Emerson, or Newman had more weight than the whole lot of the Vaishnav works. Greedily we pored over the various commentations of the Holy Bible and the labors of the Tattwa Bodhini Sabha, containing extracts from the Upanishads and the Vedanta, but no work of the Vaishnavas had any favor with us.

“But when we advanced in age and our religious sentiment received development, we turned out in a manner Unitarian in our belief and prayed as Jesus prayed in the Garden. Accidentally we fell in with a work about the Great Caitanya, and on reading it with some attention in order to discern the historical position of that Mighty Genius of Nadia, we had the opportunity of gathering His explanations of the Bhagavat given to the wrangling Vedantist of the Benares School.

‘The accidental study created in us a love for all the works which we found about our Eastern Savior. We gathered with difficulty the Kurchas [Kurchas are notebooks—Editor.] in Sanskrit, written by the disciples of Caitanya. The explanations that we got of the Bhagavat from these sources were of such a charming character that we procured a copy of the Bhagavat complete and studied its texts . . . with the assistance of the famous commentaries of Shreedhar Swami. From such study it is that we have at last gathered the real doctrines of the Vaishnavas. Oh! What a trouble to get rid of prejudices gathered in unripe years!”

Bhaktivinoda Thakura then goes on to put the position of the Bhagavata into its right perspective and to describe its philosophical and theological contents, carrying on in the process a running critique of other positions. In this he foreshadowed his effort throughout the rest of his career: to restore the Bhagavata Purana and the Caitanya tradition as a whole to respectability. It was not an easy task. As the pamphlet indicates, learned persons in general held the tradition to be unworthy of serious interest. There was thus no attention given to the great writings of the past and no current publications to elicit such attention or give access to the great treasury of devotional religion that had poured forth from Caitanya onward. Fortunately for the tradition, Bhaktivinoda Thakura not only recognized the problem but was equal to the task.

Bhaktivinoda published some hundred books during his career, most of them devoted to recovering and promoting the tradition of Caitanya. He was obviously an enormously productive person. His work habits are frightening: He would get up at 4:30 in the morning, bathe, do his bhajana (Bhajana is the (usually solitary) chanting of the Lord’s name or the singing of devotional songs.—Editor), answer correspondence, and so forth, and then at 9:00 he would go to the court. (Remember, those hundred books were written during his career as a magistrate, which is what he was supposedly spending most of his time at.) So he would go to the law court at 9:00 and finish by 5:00, with an hour’s break from 1:00 to 2:00. Then he would translate some Sanskrit religious work into Bengali from 5:00 until 7:00, have dinner, take a couple of hours’ nap, get up, and write all night from 10:00 until 4:00. Then he would rest a little bit and go through his daily routine. So he was working about eighteen to twenty hours a day, efficiently. That’s the way people describe him. And, amazingly, he also found time to raise thirteen children.

In 1881 Bhaktivinoda started a new Vaisnava journal called Sajjana-tosani to disseminate the teachings of Caitanya. At about the same time he also accepted Jagannatha dasa Babaji as his siksa-guru. (A siksa-guru is a spiritual master who imparts Vedic knowledge to someone who may or may not be his initiated disciple.—Editor). This is an example of a very interesting interaction that was taking place in the 19th century between the educated, intellectual, Westernized, highly philosophically oriented scholar types like Bhaktivinoda Thakura and the more emotional, ecstatic babaji types in the paramahamsa-sannyasa category, who were anything but scholars, who were primarily devotees to the core, and who spent most of their time doing bhajana and had no interest in scholarship at all, certainly not to do it or to promote it. But then in Bhaktivinoda Thakura—and, I think, in this whole tradition—what you get is a blending of those two components, which is really the secret of all the successful devotional movements in Indian history. They have somehow managed to bring together the intellectual dimension and the emotional dimension in a creative way; in every one of these movements there has always been that kind of merger. That merger occurred very clearly in the case of Bhaktivinoda Thakura, who was apparently equally at ease wearing a dhoti and doing bhajana or wearing a cloth coat and doing law. He moved between these two worlds with facility and understood them both.

Later on, in 1887, again to promote Caitanya’s movement of devotional service to Krsna, he began work on commentaries in Bengali on the Caitanya-caritamrta and established a printing press at Bhaktibhavan, his house in Calcutta. Printing and publishing were very early seen as the key to successful promotion of the cause. Thus technology was very early employed by Bhaktivinoda Thakura in pursuit of the religious community, and its use was carried even further by his son, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura, who would refer to the printing press as the brhat mrdanga (A mrdanga is a clay drum used in congregational chanting—Editor), “the great mrdanga.” Bhaktisiddhanta said the brhat mrdanga should supplement the ordinary mrdanga, because an ordinary mrdanga can be heard for only a couple of blocks but the printing press can be heard around the world. This image of “the great mrdanga“—publishing and printing and promoting the cause through writing, translation, and commentaries—is, again, distinctive of the Krsna consciousness movement.

In 1888, Bhaktivinoda Thakura discovered the birthplace of Caitanya, which had been forgotten. Everybody thought it was in Navadvipa, but it turned out to be in the nearby village of Mayapura. Bhaktivinoda promoted the building of a temple at that site and used that promotion as a way of generating enthusiasm for the renewal of the Caitanyite tradition. When he retired in 1894, he spent most of his time working on that project, which was successfully completed in 1895.

In 1896 Bhaktivinoda published in Sanskrit a little booklet on Caitanya, to which was attached an English preface called Caitanya Mahaprabhu: His Life and Precepts. Copies of this little booklet were sent to various places in the West. One of them ended up at McGill University Library and another at the library of the Royal Asiatic Society in London. From these efforts the Krsna consciousness movement won intellectual respectability; after all, McGill and the Royal Asiatic Society had sanctioned it.

Finally, in 1900, near the end of his life, Bhaktivinoda Thakura went to Jagannatha Puri and from that point on spent most of his time in seclusion, performing his bhajana incessantly and eventually being initiated as a babaji, a renounced person pursuing his own personal religious activities.

Bhaktivinoda’s role in the movement was taken up by his son, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura. His father had conducted all of his education, giving him a broad knowledge of English, Sanskrit, and Bengali along with an exhaustive knowledge of devotional texts and a powerful sense of the mission to spread Krsna consciousness. He set out to promote the cause and in 1915 established the Bhagavat Press to publish, and publish extensively, the literature of the Vaisnava tradition. He also strove to break down the entrenched caste prejudices in India by giving the sacred brahmana thread to every qualified candidate who presented himself for initiation, no matter what caste he came from. Thus whether the person was a sudra, an outcaste, or presumably even a non-Hindu, if he qualified religiously he could be initiated and receive the sacred thread, thereby becoming a brahmana as good as any other brahmana. Following the example of his father, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati based these actions on the teachings of the Bhagavata Purana, particularly the history of Narada, who, although raised as a sudra, was given status as brahmana because of his personal qualities of devotion and learning. So both Bhaktivinoda Thakura and Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura pushed this issue-that brahmanhood is a matter of personal quality and not of birth.

Now, out of all this we get Bhaktivedanta Swami. He really is simply the inheritor—well not simply: he’s a great person in his own right—but he is the inheritor of this tradition. He himself was given an English education at Scottish Churches’ College in Calcutta, went into business, and ran a pharmacy for many years in Allahabad. He was initiated in Allahabad by Bhaktisiddhanta, and finally he moved more and more toward the renounced life. Essentially, he spent most of his time pursuing his religious career. In 1944 he founded BACK TO GODHEAD magazine, which is now being sold by his disciples and his disciples’ disciples throughout the country. In 1959 he was initiated as a sannyasi (a sannyasi is a renunciant.—Editor), and in 1962 he published the first volume of his translation of and commentary on the Bhagavata Purana. In August of 1965 he left India for New York City, and the history after that is fairly well known.

The point I want to make is that Bhaktivedanta Swami brought with him much more than his own abilities; he brought with him a century of working through the problem of how the great tradition of the Vaisnava devotional path relates to the modern world, how that tradition can be related to the Western mentality, how it can be promoted within the West, and how it can be propagated by the acquisition of new members. For instance, new members of the Krsna consciousness organization go through a two-stage initiation. First they are simply given a religious name and beads to chant Hare Krsna on. The second initiation is the initiation into brahmanhood. But, again, this is not an American innovation. Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati had done that in India, and it was simply carried over into this country by Bhaktivedanta Swami.

For almost every one of what may seem to be innovative practices, the way was paved during the three generations before Bhaktivedanta Swami came to America. The practices were shaped for precisely the kind of situation Bhaktivedanta Swami would meet in New York City in 1965. And it’s out of that 19th-century background—unknown, to say the least, to the people to whom he was bringing his message—that this tremendous Krsna consciousness movement has emerged. The whole thing was set in place in the 19th century, and the ground was prepared for somebody with the determination and drive that Bhaktivedanta Swami had to tap the resources of Gaudiya Vaisnavism and bring it over and put it in a place where it would take root and flourish.

Leave a Reply