By Damodara dasa

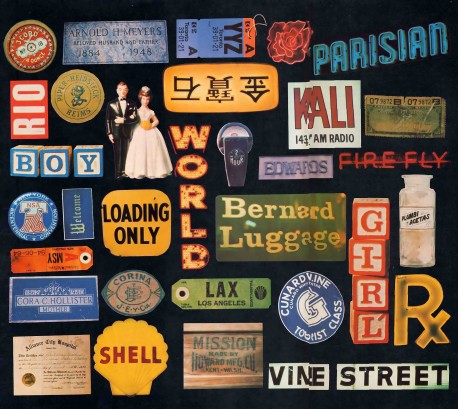

Everywhere you look there are so many names. Names for packages, names for signposts, names for places, names for plants, names for people. Names are convenient, and maybe a little confusing.

“History’s first psychotherapy session, “on a battlefield, raises a question: “John,” “Jane,” “Black,” “White,” “Girl,” “Boy,” “Student,” “Soldier”—what’s in a name?

People hailed him as a great military hero. They said he was as strong as a lion. With bow and arrow he was beyond belief: he could hit a hundred-foot-high target obscured by the spokes of a chariot wheel—even if he had to take aim by looking at the target’s rippling reflection in a water pail. More than once he’d fought off hundreds of soldiers without any help.

But today, as the time for his next battle drew near, Arjuna was shaking with anxiety. Looking over the two armies from a vantage point midway between them, Arjuna slumped down on his chariot, in despair.

His physical strength hadn’t failed him. He was still the match of any soldier on the enemy side (with the exception of Bhisma, perhaps). But even Bhisma’s skill and fortitude couldn’t have driven Arjuna into this deep depression.

The renowned warrior had lost his courage because he was about to take part in a civil war—a war in which he would be pitted against his grandfather, his father-in-law, his cousins, his uncles, and the very teacher at whose feet he’d learned the art of war. Others, too, on both sides, were now poised to plunge arrows, swords, and lances into the bodies of their relatives and superiors. Arjuna’s skin burned and his mouth dried up as he contemplated the horrible events to come.

“How can any good come from this?” he thought aloud. “What use would our victory be if we should ruin our whole society, our whole culture, in the process? We’ll rip apart the fabric of family ties, and then our civilization will lie in shreds.”

His only desire was to leave at once—to leave the battlefield and leave his profession. To go to the woods, perhaps, and take up the life of a beggar. “I’d rather live by other people’s money than by my relatives’ blood,” he decided.

Uncles, cousins, teachers, grandfathers, fathers-in-law, sons, brothers-in-law—the very network of social relationships that before had given Arjuna so much pleasure, now had driven him to a nervous breakdown. How could he kill these people? He knew the enemy soldiers by name—names that sound strange to us (like Duryodhana, Bhurisrava, Drona), but names that signified intimate relationships to him. Meditating on those names and relationships, Arjuna wept out of compassion and hopelessness.

Arjuna’s self-searching, recorded in the opening pages of the Bhagavad-gita, was a natural response to a terrifying situation. Caught in a web of conflicting social designations, he considered that his only way out was to change his own designation from “soldier” to “beggar.” But soon Arjuna’s trusted friend and teacher, Lord Krishna (the Supreme Personality of Godhead) was to show him that even as a beggar he would be unhappy. The answer, said Lord Krishna, was to stop thinking of himself as “soldier,” “‘beggar,” “student,” and start looking for his real identity on a level deeper than that. Otherwise, Krishna suggested, Arjuna’s life would be full of anxiety.

The same is true for me. It’s a commonsense fact of my life that if somebody approaches me at my job or on the street and asks me in an offhand way who I am, then I’ll probably answer with my name. Names are convenient. They make social interaction possible. How could we ever finalize legal documents, sign checks, introduce ourselves at parties, reminisce about old friends, if we didn’t use names? It would be nearly impossible.

But the name is not the same as the thing named. In this connection we usually think of Shakespeare: “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet.” How much more true that is, then, of a human being. As convenient as names are, they’re just superficial concepts of our personal identity.

Names are superficial, because, for one thing, each of us has little choice about the designations that fix us in this world, the world of names. For instance, take that triumphant cheer heard in hundreds of languages, in thousands of maternity rooms: “It’s a boy!” Suddenly, that little human being who had been a mystery, an it, has been pinned down. It’s a boy. For the parents, the relatives, the family’s friends, and for the whole culture, that means a lot. A complex structure of obligations and expectations has been set up. Starting with blue (not pink) baby clothes, moving through baseball and Boy Scouts, on through high school to high finance, that little person’s trajectory through life has to a great extent been determined for him just by the pronouncing of the word boy.

You may object that the word boy alone isn’t determining the baby’s future. It’s the condition that the word denotes. If John Doe had a baby girl and yet insisted on calling her a boy, he wouldn’t be able to make his dream come true simply on the authority of the name itself. Surely there’s a real quality, the baby’s sex, that the name is intended only to represent, and not to be. Am I stretching the point to call so much attention to a simple word?

Yes, I would be stretching the point if all we had to contend with was one or two names—”boy,” “girl” “man,” “woman” “Me Tarzan, you Jane.” Then life, and self-awareness, would be an easy job. But we don’t live in that kind of world. Like Arjuna, we live in a world of millions of names. And to make things worse, even the names we call our own are usually assigned to us before we have any choice. Somebody’s waiting for us, before we emerge, with a complete outfit of names ready to put on us. We don’t have any say in the matter. We’re controlled.

That American slang expression “handle” is a good one. In some parts of the country they’ll ask you, “What’s your handle?” if they want to know your name. That says a lot. A name is a way to control another person, to handle him. As the baby squeezes out of the womb into the world of social realities, he’s assigned all kinds of handles: “boy,” “John,” “American,” “white,” “Presbyterian,” “middle class,” “midwesterner,” “middletowner.” Before he even knows what hit him, he’s spinning in the social whirl. And by the time he’s old enough to do something about it, old enough to take control of his life, “John” is too bewildered by his designated names, and by the superficial qualities they represent, to be able to sense his deeper, personal qualities.

Psychologist Rollo May quotes one of his patients as saying, “I’m just a collection of mirrors, reflecting what everyone else expects of me.” In a well-known survey of the 1950’s, a distraught American housewife made this disclosure:

I’ve tried everything women are supposed to do-hobbies, gardening, pickling, canning, being very social with my neighbors, joining committees, running PTA teas. I can do it all, and I like it, but it doesn’t leave you time to think about-any feeling of who you are. There’s no problem you can even put a name to. But I’m desperate. Who am I?

“There’s no problem you can even put a name to,” the lady laments. But names are her problem. She’s been assigned too many names, none of them getting to the heart of her personal identity. Today’s foremost scholar of the Bhagavad-gita, His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, suggests a cure for the problem of names:

American, or Indian, or German, or Englishman; cat or dog, or bee or bat, man or wife: all of these are designations. In spiritual consciousness we become free from all such designations.

Many people have fought against the false limitations imposed on them by superficial designations, many have tried to become free. In the 1960s Theodore Roszak wrote, “The bohemian fringe of our youth culture… is grounded in an intensive examination of the self, of the buried wealth of personal consciousness.” Today the beat goes on in a more respectable way. In a September 13, 1976, Newsweek article on genealogy (“perhaps the fastest-growing hobby in America”), the writers noted,

Although genealogy’s uses range from investigating possible hereditary causes of cancer to settling estate disputes, the single most compelling reason for its new popularity comes down to the question “Who am I?”

And the problem of identity is deeply enmeshed in one of the longest standing, most divisive issues in American culture-the racial problem. The names “black” and “white” have stirred destructive emotions since the 1600s. In his autobiographical novel of 1937, Black Boy, Richard Wright told of his struggle to get free from designations:

The white South said it knew “niggers,” and I was what the white South called a “nigger.”

Well, the white South had never known me—never known what I thought, what I felt… The pressure of Southern living kept me from being the kind of person that I might have been. I had been what my surroundings had demanded, what my family—conforming to the dictates of the whites above them—had expected of me, and what the whites had said that I must be.

Having decided “that the South could recognize but part of a man,” Wright moved north to Chicago in his search for freedom. Some people move north, some take drugs, some hire genealogists or psychologists. They want to leave, as Arjuna did, the artificial conflicts brought upon them by designations assigned to them by others.

How superficial those conflicts are! Because others have assigned me certain names, or because circumstances have put me in a certain position, I’m forced into conflicts I can’t avoid-simply because of the social commitments my name implies. If I’m a Hatfield, then I must be against the McCoys. If I’m a fifth-century-B.C. Athenian, then I must fight against the Spartans. If today I’m a Northern Irish Catholic, then I must fight the Protestants. Owners vs. Workers. Black vs. White. Men vs. Women. Town vs. Gown. “Anybody over thirty can’t be trusted.” This is very frustrating for me because I’m not really fighting for my rights, or perhaps not even for anything I believe in if given a chance to think about it. I’m defending something superficial, which somebody else most likely assigned to me without my asking for it.

To be sure, we can change some of our designations. Age, of course, changes anyway, of its own accord. Then, I can change my educational status, my occupation, my social class, or perhaps my given name, if I’m determined. And some people in extreme circumstances even decide to change their sex (the 1975 Obstetrics and Gynecology Annual reports that “it is apparent that several thousand transsexuals of both sexes live in the U.S. today”). Or, in protest, like many draft evaders during the Vietnam War, I could emigrate to Canada or Sweden and change my citizenship. On the other hand, as a last resort, I might try to shed all my names, escape from all my qualities, to become “one with the void,” as some Buddhists do.

But these reactions to discontent are probably as meaningless as the conflicts that caused the discontent. Without a look deeper within, a mere shuffling around of names or superficial qualities isn’t going to help. As Lord Krishna told Arjuna, “of the nonexistent there is no endurance, and of the existent there is no cessation.” In other words, things that change aren’t real, and things that are real don’t change. Changing names isn’t going to free us from the tyranny of names.

That could leave us in a pretty desperate place, were it not for a simple feeling that we’ve all had. It comes out in your life in a natural way, because it’s a natural thing to feel. It’s almost like changing names, but it isn’t really, because it’s just a matter of discovering the identity you already have but just aren’t aware of. It’s a matter of finding your permanent name.

With proper direction, this feeling of permanent identity, or permanent consciousness, can lead to great things. And the first step is very simple. We ask, “What is the identity that I have throughout life, that I can’t change even by the most drastic measures?” Let’s not think of changing. Let’s think of that which we cannot change. Now, there may be many answers to this question. But it seems the most meaningful answer for us right now would be something like this: “I am a human being.” Yes, “human being” is a name. But at least for this lifetime it’s a permanent name. With this understanding, we jump the first hurdle—the most difficult hurdle—on the path of liberation from the tyranny of names.

Still, that name “human being” can easily turn into a cliche, a sentimental catchword as bad as any other. It might go no further than sending UNESCO Christmas cards to the people on your mailing list. So we need to know the implications of this label “human being.” What is the essence of a human being? What makes man so different from the other animals? So many philosophers and anthropologists have spoken and written so many words on this subject that it may seem impossible to come to a final definition.

But with a little careful study, we can make out a clear pattern in most of the attempts. I don’t have the space to indulge in full-scale analysis, but I hope a few examples will suffice. For instance, Kierkegaard said that man is unique because “he can concentrate his entire energy upon the fact that he is an existing individual.” Again, Rollo May has noted, “man is very different from the rest of nature. He possesses consciousness of himself; his sense of personal identity distinguishes him from the rest of living or nonliving things.” We hardly need to go on, except perhaps to hark back to that classic statement of Plato’s:

Self-knowledge would certainly be maintained by me to be the very essence of knowledge, and in this I agree with him who dedicated the inscription “Know Thyself!” at Delphi.

Rene Descartes was one who undertook to know himself. After formulating his famous statement, “I think, therefore I am,” he said,

I thence concluded that I was a substance whose whole essence or nature consists only in thinking, and which, that it may exist, has need of no place, nor is dependent on any material thing; so that “I,” that is to say, the mind [soul] by which I am what I am, is wholly distinct from the body, and is even more easily known than the latter.

This ability of ours to inquire about our identity—the very size and sophistication of the human brain underscores this ability—receives much clearer definition in the Vedic literature of India. There we read that self-realization is the law of human life, just as swimming is the law of fish life, and flying is the law of bird life. Each kind of body is meant for a particular purpose, and if that purpose isn’t fulfilled, then that animal has wasted its life. So if the human animal doesn’t spend his time seriously inquiring into the quality of the self, then he is, so to speak, breaking the law of human life.

Our life in these human bodies isn’t something neutral. The body may be a machine, but still we have feelings, and we can’t deny that for much of life our feelings are painful. Arjuna on the battlefield, the confused housewife at her PTA teas, Richard Wright in the South—they all were suffering. In his introduction to the Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Srila Prabhupada writes about this point:

Every man is in difficulty in so many ways, as Arjuna was also in difficulty in having to fight the Battle of Kuruksetra. Arjuna surrendered unto Lord Krishna, and consequently this Bhagavad-gita was spoken. Not only Arjuna, but every one of us is full of anxieties because of this material existence. Our very existence is in the atmosphere of nonexistence. Actually we are not meant to be threatened by nonexistence. Our existence is eternal…

Out of so many human beings who are suffering, there are a few who are actually inquiring about their position, as to what they are, why they are put into this awkward position, and so on. Unless one is awakened to this position of questioning his suffering, unless he realizes that he doesn’t want suffering but rather wants to make a solution to all sufferings, then one is not considered to be a perfect human being. Humanity begins when this sort of inquiry is awakened in one’s mind.

The message, then, coming to us from those who’ve researched the problems of living, is that human life is meant for self-knowledge. Of all life forms, only man can understand the purpose of existence—to break free from the suffering brought on by illusory names, and to gain happiness in real selfhood.

On the battlefield, Lord Krishna and Arjuna discussed the science of self-knowledge at length. Krishna told His friend that the self is spiritual: “For the self there is never birth nor death. Nor, having once been, does he ever cease to be… He is not slain when the body is slain… As a person puts on new garments, giving up old ones, similarly the soul accepts new material bodies, giving up the old and useless ones.”

Krishna appealed to Arjuna’s reason and direct perception and brought him from a fragmented, name-bound concept of self to a higher awareness of his personal existence, beyond material conflicts. Secure in self-knowledge, Arjuna could then choose a role for himself that fully satisfied his spiritual nature. In other words, he could see his real spiritual identity—neither warrior nor beggar but an eternal servant of God.

By the end of Arjuna and Krishna’s dialogue (the end of the Bhagavad-gita), Arjuna was cured of his anxiety. A person who studies their conversation today can get the same benefit. One scholar has termed it “history’s first psychotherapy session,” and for countless people the first is still the best.

Leave a Reply