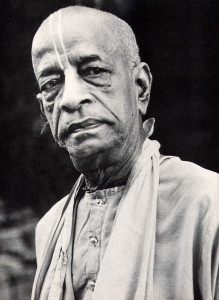

The Biography of a Pure Devotee

by Srila Satsvarupa dasa Goswami

Eager to fulfill his spiritual master’s request that he teach the science of Krsna consciousness to Westerners, Srila Prabhupada welcomed anyone and everyone into his little storefront temple on the Lower East Side.

Eager to fulfill his spiritual master’s request that he teach the science of Krsna consciousness to Westerners, Srila Prabhupada welcomed anyone and everyone into his little storefront temple on the Lower East Side.

Prabhupada retired through the rear door, back up to his apartment, his guests would disappear through the front door, back into the city. Don and Raphael would turn out the lights, lock the front door, and go to sleep on the floor in their blankets.

Don and Raphael had needed a place to stay, when they heard about the Swami’s place. Prabhupada had a policy that any boy who expressed even a little interest in becoming his student could stay in the storefront and make it his home, Of course, Prabhupada would ask them to contribute towards the rent and meals, but if, like Don and Raphael, they had no money, then it was still all right, provided they helped in other ways,

Don and Raphael were the first two boys to take advantage of Prabhupada’s offer. They were attracted to Prabhupada and the chanting, but they weren’t serious about his philosophy or the disciplines of devotional life. They had no jobs and no money, their hair was long and unkempt, and they lived and slept in the same clothes day after day, Prabhupada stipulated that at least while they were on the premises they could not break his rules—no intoxication, illicit sex, meat-eating, or gambling. He knew these two boarders weren’t serious students, but he allowed them to stay, in hopes that they would become Krsna conscious and help him sometimes.

Often, some wayfaring stranger would stop by, looking for a place to stay the night, and Don and Raphael would welcome him. An old white-bearded Indian-turned-Christian who was on a walking mission proclaiming the end of the world, and whose feet were covered with bandages, once slept for a few nights on a wooden bench in the storefront. Some nights as many as ten drifters would seek shelter at the storefront, and Don and Raphael would admit them, explaining that the Swami didn’t object, as long as they got up early. Even drifters whose only interest was a free meal could stay, and after the morning class and breakfast they would usually drift off again into maya.

Don and Raphael were the Swami’s steady boarders, although during the day they also went out, returning only for meals, sleep, and evening chanting. Occasionally they would bathe, and then they would use the Swami’s bathroom up in his apartment. Sometimes they would hang out in the storefront during the day, and if someone stopped by, asking about the Swami’s classes, they would tell the person all they knew (which wasn’t much). They admitted that they weren’t really into the Swami’s philosophy, and they didn’t claim to be his followers. If someone persisted in inquiring about the Swami’s teachings, Don and Raphael would suggest, “Why don’t you go up and talk to him? The Swami lives in the apartment building out back. Why don’t you go up and see him?”

Prabhupada usually stayed in his apartment. Occasionally he might look out his window and see that the light in the closetsized bathroom had needlessly been left burning. Coming down to ask the boys to turn it off and not waste electricity, he might find a few boys lying on the floor talking or reading. Prabhupada would stand gravely, asking them not to leave the light on, stressing the seriousness of wasting Krsna’s energy and money. He would stand dressed in khadi, that coarse handloomed cotton woven from handspun threads, a cloth that to Americans appears somehow exotic. Even the saffron color of Prabhupada’s dhoti and chadar was exotic; produced from the traditional Indian rock dye, it was a dull, uneven color, different from anything Western. After Prabhupada turned off the light, the boys seemed to have nothing to say and nothing more appropriate to do than look with interest at him for a long awkward moment, and Prabhupada would leave without saying anything more.

Money was scarce. From his evening meetings he would usually collect about five or six dollars in change and bills. Don talked of going up to New England to pick apples and bring money back for the Swami. Raphael said something about some money coming. Srila Prabhupada waited, and depended on Krsna. Sometimes he would walk back and forth in the courtyard between the buildings. Appearing mysterious to the neighbors, he would chant on his beads, his hand deep in his bead bag.

Mostly he kept to his room, working. As he had said during a lecture when living on the Bowery, “I am here always working at something, reading or writing, some kind of reading or writing—twenty-four hours.” His mission of translating Srimad-Bhagavatam, of presenting the complete work in sixty volumes of four hundred pages each, could alone occupy all his days and nights. He worked at it whenever possible, sitting at his portable typewriter or translating the Sanskrit into English. He especially worked in the very early hours of the morning, when he would not be interrupted. He would comb through the Sanskrit and Bengali commentaries of the great acaryas, following their explanations, selecting passages from them, adding his own knowledge and realization, and then weaving it all together and typing out his Bhaktivedanta purports. He had no means or immediate plans for financing the publishing of further volumes, but he continued in the faith that somehow they would be published.

He had a broad mission, broader even than translating Srimad–Bhagavatam, and so he gave much of his time and energy to meeting visitors. Had his aim been only to write, there would have been no need of his taking the risk and trouble of coming to America. Now many people were coming, and an important part of his mission was to talk to them and convince them of Krsna consciousness. His visitors were usually young men who had recently come to live on the Lower East Side. He had no secretary to screen his visitors, nor did he have scheduled visiting hours. Whenever anyone happened by—at any time, from early morning to ten at night—Prabhupada would stop his typing or translation and speak with them. It was an open neighborhood, and many visitors would come in right off the street: Some were serious, but many were not; some even came intoxicated. Often they came not to inquire submissively, but to challenge.

Once a young hippie on an LSD trip found his way upstairs and sat opposite Prabhupada: “Right now I am higher than you are,” he announced. “I am God.” Prabhupada bowed his head slightly, his palms folded: “Please accept my obeisances,” he said. Then he asked “God” to leave. Others admitted frankly that they were crazy or haunted by ghosts and were searching for relief from their mental suffering.

I was looking for spiritual centers—places where one can go, not like stores where they ask you to leave, but where you can actually talk to people and try to understand the ultimate truth. I would come to the Swami’s, knowing it was definitely a spiritual center. There was definitely something there. I was on drugs and disturbed with the notion that I must be God, or some very important personality way out of proportion to my actual situation. I was actually in trouble, mentally deranged because of so much suffering, and I would kind of blow in to see him whenever I felt the whim to do so. I didn’t make a point of going to his meetings; but a lot of times I would just come. One time I came and spent the night there. I was always welcome at any time to sleep in the storefront. I wanted to show the Swami what a sad case I was, so he should definitely do something for me. He told me to join him and he could solve my problems. But I wasn’t ready.

I was really into sex, and I wanted to know what he meant by illicit sex—what was his definition. He said to me, “This means sex outside of marriage.” But I wasn’t satisfied with the answer, and I asked him for more details. He told me to first consider the answer he had given me and then come back the next day and he would tell me more.

Then I showed up with a girl. The Swami came to the door and said, “I am very busy. I have my work, I have my translating. I cannot talk with you now. ” Well, that was the only time he didn’t offer me full hospitality and full attention and talk with me as many questions I had. So I left immediately with the girl. He was correct in his perception that I was simply going to see him just to try to impress the girl. He saw through it right away, and he rejected that type of association.

But every time I came and I was in trouble, he always helped me.

Sometimes young men would come with scholarly pretensions to test Prabhupada’s knowledge of Bhagavad-gita. “You have read the Gita,” Prabhupada would say, “so what is your conclusion? If you claim to know the Gita, then you should know the conclusion that Krsna is presenting.” But most people didn’t think there was supposed to be a definite conclusion to the Gita. And even if there was such a conclusion, that didn’t mean they were supposed to arrange their life around it. The Gita was a spiritual book, and you didn’t have to follow it.

One young man approached Prabhupada asking, “What book will you lecture from next week? Will you be teaching the Tibetan Book of the Dead?” as if the Swami would teach spirituality like a college survey course in World Religions. “Everything is there in Bhagavad-gita,” Prabhupada replied. “We could study one verse for three months.”

And there were other such questions: “What about Camus?”

“What is his philosophy?” Prabhupada would ask.

“He says everything is absurd and the only philosophical question is whether to commit suicide.”

“That means everything is absurd for him. The material world is absurd, but there is a spiritual world beyond this one. That means he does not know the soul. The soul cannot be killed.”

Adherents of different thinkers approached him: “What about Nietzsche? Kafka? Timothy Leary? Bob Dylan?” Prabhupada would ask what each of their philosophies was, and the particular follower would have to explain and defend his favorite intellectual hero.

“They are all mental speculators,” Prabhupada would say. “Here in this material world we are all conditioned souls. Your knowledge is imperfect. Your senses are blunt. What good is your opinion? We have to hear from the perfect authority, Krsna.”

“Do you mean to say that none of the great thinkers are God conscious?” a boy asked.

“Their sincerity is their God consciousness. But if we want perfect knowledge of God, then we have to consult sastra.”

Often there were challenges, but under the Swami’s piercing gaze and hard logic, the challenger would usually trail off into thoughtful silence.

“Is the spiritual knowledge of China advanced?”

Prabhupada would sometimes answer simply by making a sour face.

“Well, I am a follower of Vedanta myself.”

“Do you know what ‘Vedanta’ means? What is the first aphorism of the Vedanta-sutra? Do you know?”

“No, I…

“Then how can you speak of Vedanta? Vedais ca sarvair aham eva vedyah: Krsna says that He is the goal of Vedanta. So if you are a Vedantist, then you must become Krsna conscious.”

“What about the Buddha?” “Do you follow him?” “No:’

“No, you just talk. Why don’t you follow? Follow Krsna, follow Christ, follow Buddha. But don’t just talk.”

“This sounds the same as Christianity. How is it any different?”

“It is the same: love of God. But who is a Christian? Who follows? The Bible teaches, ‘Thou shalt not kill,’ but all over the world, Christians are expert in killing. Do you know that? I believe the Christians say that Jesus Christ died for our sins—so why are you still sinning?”

Although Prabhupada was a stranger to America, they were strangers to absolute knowledge. Whenever anyone would come to see him, Prabhupada wouldn’t waste time—he talked philosophy, reason, and argument. He constantly argued against atheism and impersonalism. He spoke strongly to prove the existence of God, and the universality of Krsna consciousness. He talked often and vigorously, day and night, meeting all kinds of questions and philosophies.

He would listen also, and he heard a wide range of local testimonies. He heard the dissatisfaction of young Americans with the war and with American society. One boy told him he didn’t want to get married because he couldn’t find a chaste girl; it was better to go with prostitutes. Another confided that his mother had planned to abort him but at the last moment his grandmother had convinced her not to. He heard from homosexuals. Someone told him that a set of New Yorkers considered it chic to eat the flesh of aborted babies. And in every case, he told them all the truth.

He talked with Marxists and explained that although Marx says everything is the property of the State, in fact everything is the property of God. Only “spiritual communism,” which puts God in the center, can really be successful. He discounted LSD visions as hallucinations and explained how God can actually be seen and what He looks like.

Although many of these visitors came one time and went away, a few new friends began to stay on, watching the Swami deal with the various guests. They began to appreciate the Swami’s arguments, his concern for people, and his devotion to Krsna. He seemed actually to know how to help people, and he invariably offered them Krsna consciousness—as much as they could take—as the solution to their problems. A few began to appreciate his message seriously.

(To be continued)

Leave a Reply