An Offering of Love at Every Moment

by Dravida dasa

Ask anyone who lives near the New Vrindaban farm community, Who built Prabhupada’s Palace? and chances are they’ll say, “Oh, the Hare Krsnas built it.” Ask the devotees, and they’ll all say, “Srila Kirtanananda Swami Bhaktipada built the Palace. We just helped him.” And ask Srila Bhaktipada himself, and he’ll likely say, “Lord Krsna built it, working through the devotees.”

These answers are all correct in their own way. First, the building of the Palace was indeed the work of the Krsna devotees at New Vrindaban. During the seven years it took to complete, everyone pitched in with whatever talents and energy he could bring to bear. Some spent day after day crouched on a scaffold, painstakingly applying gold leaf. Others poured and mixed concrete by hand, even in the bitter-cold West Virginia winters. Still others carved wood and glass, painted ceilings, cast architectural ornaments, landscaped the grounds, or cut and laid marble. Though modest in size compared to the great cathedrals of Europe and the magnificent temples of India, Prabhupada’s Palace ranks beside them as an expression of collective devotion and sacrifice of the highest order.

But the Palace is first and foremost an expression of Srila Bhaktipada’s devotion to his spiritual master, His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada.

It was Srila Bhaktipada who started the New Vrindaban community, at the request of Srila Prabhupada, back in 1968; it was Srila Bhaktipada who conceived and developed the idea of the Palace; and it was Srila Bhaktipada who personally guided, encouraged, and inspired the devotees through every step of the arduous construction. So, in an important sense, Srila Prabhupada’s Palace is also Srila Bhaktipada’s palace.

Finally, devotees of Krsna understand that ultimately it is Krsna Himself who built Prabhupada’s Palace. When Krsna sees that His devotees have a strong desire to perform a certain service for Him—especially one that glorifies His most exalted servitor—He empowers them to do it and provides all necessities in abundance. So it was Lord Krsna, through His various energies, who supplied the marble, the cement, the gold, and even the muscle and intelligence the devotees used to build the Palace. But the devotion, the love, and the strong determination to push through all difficulties and create something wonderful to glorify Srila Prabhupada—these the devotees themselves brought to the task. And it is these qualities that glow from every inch of the Palace.

On the following pages we meet a few of the many devotees whom Krsna especially empowered to build Srila Prabhupada’s Palace of Gold.

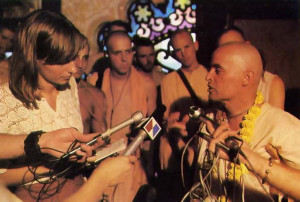

If we were to try to single out one person responsible for Prabhupada’s Palace, the only possible choice would be His Divine Grace Kirtanananda Swami Bhaktipada. One of the first and most intimate disciples of Srila Prabhupada, Srila Bhaktipada began the New Vrindaban farm community in 1968 at his request and nurtured it through its first few difficult years.

If we were to try to single out one person responsible for Prabhupada’s Palace, the only possible choice would be His Divine Grace Kirtanananda Swami Bhaktipada. One of the first and most intimate disciples of Srila Prabhupada, Srila Bhaktipada began the New Vrindaban farm community in 1968 at his request and nurtured it through its first few difficult years.

In 1971 he left New Vrindaban for some time to travel around the United States by bus, teaching the message of Krsna consciousness in colleges and universities and through the media.

By 1972 Srila Bhaktipada had returned to New Vrindaban, and in 1973 he began to contemplate how to fulfill a desire Srila Prabhupada had for the community: the construction of a temple on each of seven of the farm’s hills. Srila Bhaktipada explains how the Palace grew out of this project: “In 1973 we were getting ready to start a temple for Krsna at the Govindaji site down at Bahulabana [the principal farm at New Vrindaban]. We had already done the preliminary excavation work and dug a little footer. But I began to think, ‘This is not very proper. We are building a home for Krsna, but actually in our community there is no home for Srila Prabhupada.’ So I thought, ‘Let us build a home for Srila Prabhupada, because that is the proper way to approach Krsna.’ If we want to render service to Krsna, we first have to render service to His devotee.

“So we began. But as we worked on Prabhupada’s home, it began to take on the shape of a palace. So the Palace gradually developed.”

During the first years of the Palace construction, men and money were scarce, and the seemingly impossible task of building an elaborate Vedic temple in the hilly backwoods of West Virginia would have stopped an ordinary man cold. Not Srila Bhaktipada. His intense devotion and love for Srila Prabhupada, and his equally intense desire to see him glorified royally, kept the devotees enthusiastic to complete the project.

“Srila Bhaktipada was everywhere,” relates one devotee who worked on the Palace from the beginning. “He was ferrying devotees and supplies up and down the three-mile road from the main farm to the Palace; he was making sure we all had prasadam [sanctified food] during those long marathon nights before the grand opening two years ago; he was observing our work to make sure we did it as he wanted it done—perfect for Prabhupada. He was always encouraging us, inspiring us, and, when necessary chastising us.”

As Srila Bhaktipada said in a recent interview with Professor Harvey Cox of Harvard Divinity School: “In graduate school I was simply approaching [religion]from the academic point of view, like trying to know the taste of honey by licking the bottle on the outside. So in the end I decided that rather than simply record religious history, I would make religious history.” Srila Bhaktipada has certainly made religious history by building Prabhupada’s Palace of Gold, and by all indications this is only the beginning.

Art for Bhagavatananda dasa, structural engineer and sculptor for the Palace, found its meaning in a Sanskrit scripture praising the Supreme Lord, Krsna. “There Krsna is described as vidagdha,” he explains, “meaning ‘He who lives wonderfully at the height of beautiful artistic craftsmanship.’ That same book explains how, since each of us is part and parcel of Krsna, we each possess the qualities of Krsna in minute degree. I happen to have a little artistic ability, so I’ve made it my purpose in life to glorify Krsna with my craft—to create a beautiful place for Krsna and His pure devotee Srila Prabhupada to live in and be worshiped.”

Bhagavatananda (formerly Joseph Cappelletti of Norristown, Pennsylvania) came to New Vrindaban from New York City in 1970 and helped Srila Bhaktipada construct the first few houses in the fledgling community. By 1972 they were planning out Srila Prabhupada’s residence, which gradually grew into the Palace.

Over the past six years, Bhagavatananda has assumed a variety of duties in the Palace construction, from engineering the massive 300-ton dome to sculpting the peacocks, elephants, and ornamental pieces that adorn the walls and columns. His present assignment is the design and execution of The Garden of Time, which will include a revolving circular fountain that traces in four-foot-high figurines the soul’s journey from birth to death to reincarnation.

Bhagavatananda sees the significance of the Palace in cultural as well as devotional terms. “Architecture reflects the stability and historicity of a people or tradition,” he explains. “The Palace is a monument to the Lord’s pure devotee Srila Prabhupada; but it is not a mere memorial to someone no longer present. It is a living tribute to the greatness of his work. It is a place of daily worship, and proof that his mission of establishing Krsna culture around the world is being fulfilled.”

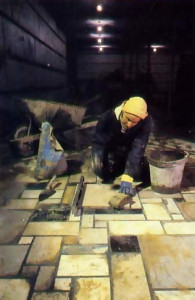

Nityodita dasa (formerly Carlos Ordonuz of Buffalo, New York) did construction work on the Palace almost from its inception eight years ago. Like nearly all the devotees who built the Palace, he learned his skills on the job, mixing and laying cement by hand and using pick and shovel for excavation during the many months before the acquisition of machinery.

He recalls how the plans for the Palace changed over the years: “When we first started work on the Palace, it wasn’t going to be a Palace at all. It was simply planned as a modest yet comfortable country home for Srila Prabhupada. But as the project developed, Srila Bhaktipada kept making the plans more and more elaborate—all for the pleasure of Srila Prabhupada. We all felt that actually we weren’t building the Palace so much as the Palace was building us into better devotees. Our devotion to Krsna was developing by our helping Srila Bhaktipada offer something wonderful to Srila Prabhupada. This is the real secret of how the Palace was built: It didn’t depend on any one worker or group of workers or on money or machinery, but on the strength of Srila Bhaktipada’s love for Srila Prabhupada. This was the inspiration for all of us to keep going through the greatest difficulties.

“Before I came to New Vrindaban I worked in a food co-op in Ann Arbor, Michigan. I had high hopes then for living an ideal life in the country and doing good for people. But there was little cooperation in the co-op, and all the people I worked with were basically materialistic and self-centered. Now I know that real cooperation can come only when we agree to work for Lord Krsna under the guidance of a pure spiritual authority. Then amazing things like Prabhupada’s Palace become possible.”

Nityodita’s latest construction project consists of helping to lay the marble floors of the new restaurant at the Palace.

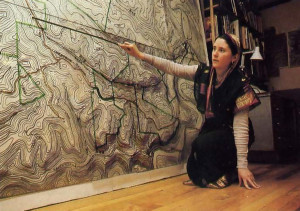

Of all the people who took part in the Palace construction, few are as familiar with the details as Sanatha-devi dasi (formerly Susanne Parmelle of Washington, D.C.), who shared in the research and design and supervised much of the labor. A graduate in structural engineering from Pratt Institute in New York City, she was responsible for drawing up working blueprints for approval by state and county officials, and for coordinating the efforts of the other workers—marble layers, stained-glass fitters, plumbers, electricians, casters, cement layers, and many others. Sometimes only Sanatha knew how to do sonic special task, like pouring five thousand square feet of concrete for the restaurant roof and tying the reinforcing rods, and then she would have to spend days with the construction crews.

“One especially wonderful thing about the Palace is that it is actually a simple, basic design—like the whole life of a devotee: a simple design made beautiful by devotion.

“That’s how I came to Krsna consciousness. I was looking for an uncomplicated way to structure my life. In architectural school I could see that both the students and the teachers were motivated only by the desire for sense gratification and fame. They didn’t care at all how the buildings they built affected people’s consciousness.

“But the Palace is not like modern architecture, where everything is designed complex and expensive. Here in the Palace a window is just two columns and a beam; but the workmanship—stained glass, relief carving, sculpted enclosure—makes it something special, because it has been done with love for Krsna.”

Sanatha explains that in the Palace a pattern often repeats itself many times. For example, the doors, windows, and terrace railings have all been cast from one original design and then finished in various ways, proving that simplicity doesn’t have to be dull.

She says that state officials were skeptical at first as to whether devotees could do such challenging work. “I remember inspectors from the environment board making regular visits because they doubted that we could build an adequate sewage system. But the devotees did such a professional job that the inspectors were amazed. The septic pond is literally sculpted out of the land—a work of art.”

Apart from the superior quality of the work, Sanatha appreciates the spirit of the Palace as well. “This structure was built first to glorify God. Architecturally, therefore, it has the highest functional use. Anyone who comes to the Palace will be inspired, and he will go away a little bit better spiritually. The way the landscaping is done, you can see God’s creation on all sides.”

Sanatha looks forward to working on other New Vrindaban construction projects: six temples (including one the size of two football fields), a school. four guest pavilions and summer festival halls, and a crafts center for the many workshops run by devotees.

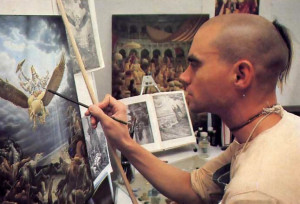

When Mark Missman left Northwest Missouri State college in 1969 after three years as an art major, he thought he was leaving behind his brushes and easel for good. He was looking for self-realization, and his art career just seemed to be an impediment. But after a short time in the San Francisco Hare Krsna temple, Mark (now Muralidhara dasa) happily discovered that he could have both his art and his self-realization.

When Mark Missman left Northwest Missouri State college in 1969 after three years as an art major, he thought he was leaving behind his brushes and easel for good. He was looking for self-realization, and his art career just seemed to be an impediment. But after a short time in the San Francisco Hare Krsna temple, Mark (now Muralidhara dasa) happily discovered that he could have both his art and his self-realization.

Explains Muralidhara: “I had sketched a picture of Krsna, and the devotees showed it to Srila Prabhupada. He asked to see me, and when I came into his room he said, Just as Arjuna used his fighting ability to serve Krsna, you should use your artistic talent. Just use this talent in Krsna’s service, and your life will be glorious.”‘

Since then Muralidhara has executed dozens of exquisite paintings depicting the pastimes of Lord Krsna, His incarnations, and His devotees. The originals grace the walls of Krsna temples around the world, while full-color reproductions illustrate Srila Prabhupada’s books and the pages of BACK TO GODHEAD magazine.

In 1978 Muralidhara came to New Vrindaban to help decorate Srila Prabhupada’s Palace. The two large oval murals on the temple’s vaulted ceiling are his work. The one nearest the altar portrays Krsna’s rasa dance, a pastime glorified in Vedic scriptures as the epitome of loving exchange between the Lord and His most intimate devotees. The other mural shows Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu, the incarnation of Lord Krsna who propagated love of God through the chanting of Hare Krsna, dancing and chanting with His close associates.

Today Muralidhara is busier than ever using his artistic skill in Krsna’s service. Besides designing a series of murals for the new restaurant at the Palace, he has recently completed two murals for the Civic Center Auditorium in Wheeling (please see news story, page 19). In addition, Muralidhara is the coordinator of design, placement, and subject matter for all the paintings at the Palace. And with a museum and a new temple in the works at New Vrindaban, it looks like Muralidhara has a full lifetime of transcendental painting ahead of him.

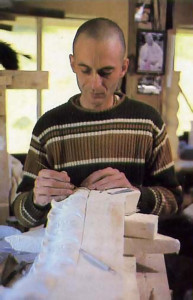

Sudhanu dasa (formerly George Weisner of Newark, New Jersey) always had a practical bent. Whatever was necessary, he would do or learn how to do. So, when the plans for Prabhupada’s Palace began to take shape back in 1975 and it became clear that a lot of fine decorative work would be needed, he went to India to learn how to carve.

Sudhanu dasa (formerly George Weisner of Newark, New Jersey) always had a practical bent. Whatever was necessary, he would do or learn how to do. So, when the plans for Prabhupada’s Palace began to take shape back in 1975 and it became clear that a lot of fine decorative work would be needed, he went to India to learn how to carve.

His first stop was Bombay, where he spent two months with a family noted for the excellence of their carved wooden pieces. Next he traveled north about five hundred miles to Jaipur, India’s center for decorative temple arts, where he studied how to carve in stone. Finally he visited a town near Jaipur called Makrana to learn the art of how to use carved marble in architecture.

On returning to New Vrindaban, Sudhanu helped devotee-artist Bhagavatananda dasa set up a marble-cutting shop. But then they contemplated the design of the Palace, which was eventually to encompass hundreds of decorative balusters, richly ornamented capitals and roof brackets, and scores of delicately embellished arches, spires, and pillars. It was obvious that they wouldn’t be able to carve everything. So Sudhanu set out to learn the art of molding . . .

He recently outlined the procedure he used in constructing the Palace: “First Srila Bhaktipada and I would consult on an idea for an architectural mold. Then I’d carve a model from clay, wood, glass, or marble—we even used plastic sometimes—and from the model I’d design a production mold out of rubber or fiberglass Then the casting could begin. mostly in concrete for the palace. On the average the whole process took from three to five weeks. Of course, a piece with many components would take longer. The central ornament inside the main dome, with 4,200 separate cast pieces. took months to create.”

Many people who come to the Palace say that Sudhanu’s work is so expertly done that they can’t tell the difference between his cast pieces and those laboriously carved by hand. And now that the Palace hosts yearly festivals for devotees and guests, Sudhanu’s work has attracted orders from all over the world. Krsna centers in Montreal, Vancouver, Washington D.C., New York, and Zurich will soon boast castings by Sudhanu. And he’s still learning new techniques. like the art of casting synthetic marble, which will be essential for constructing the huge new Krsna temple now in planning. With this technique he can faithfully reproduce the texture, colors, and patterns of the finest marbles in the world.

For Sudhanu, who regarded the construction of the Palace as “not just the building of a beautiful structure but an offering of love at every moment,” there will always be plenty to do. and more to learn.

The Palace is lit with chandeliers hand-crafted and designed by Isani devi dasi (formerly Ellen Schramm of Williamsburg, Virginia), who has been a devotee of Lord Krsna for nine years. She also created the jewelry and crowns worn by the Deities of Krsna and His consort, Srimati Radharani, and by the molded form of Srila Prabhupada at the Palace.

The Palace is lit with chandeliers hand-crafted and designed by Isani devi dasi (formerly Ellen Schramm of Williamsburg, Virginia), who has been a devotee of Lord Krsna for nine years. She also created the jewelry and crowns worn by the Deities of Krsna and His consort, Srimati Radharani, and by the molded form of Srila Prabhupada at the Palace.

For her creations Isani used fine crystal imported from Austria and Czechoslovakia. She cut and reshaped each piece and then colored each crystal “drop” so that the chandeliers complemented the stained-glass windows facing them. Next she gold-leafed the structural pieces of each chandelier to reflect the Palace motif. And all this without any previous training.

“Since I had to learn everything as I worked,” she explains, “I also had to develop extreme patience. Along with learning a new skill, I learned that there is as much pleasure in working for Krsna as in seeing the result. In other words, the work taught me a lot about devotion to God.”

For her jewelry Isani borrowed ideas from books on classical Indian and European designs. Additional instruction came from visits to the largest jewelry workshops in the United States, where she learned the intricate techniques of electroplating and electroforming (a process of producing molded objects by electrolysis). “The real problem in doing the Deity’s jewelry,” she says, “was that nobody makes such pieces anymore. Crowns, scepters—any structural problems with these had to be solved by me alone. The professional jewelers just couldn’t relate to processes like chasing, repoussee, and filigree. I had to solve the problems myself.”

But solve them she did, to the amazement of jewelry makers and distributors who have seen her work. A representative from Tiffany’s declared that much of the work surpassed his own abilities, and several suppliers of jewelry-making equipment and stones now display photographs of her work in their showrooms.

What is the secret of Isani’s expertise? “If you know whom you are making something for,” she says, “you can know how to make it best. My work is an offering of love to Lord Krsna. It’s an effort to please Him. After all, if you want to make the most beautiful thing, you should do it for the most beautiful person—God.”

Isani says her work for the Palace was just the beginning. Not only are more temples already under construction at New Vrindaban, but she receives orders daily from visitors who have admired her pieces and want to buy reproductions. Favorites are the forty portico chandeliers, uniquely designed to hang so that light is beautifully reflected from the mirrored ceiling of the Palace hallways.

Isani is married to another Krsna devotee, Samba dasa, who’s in charge of the crew that hauls heavy equipment and supplies for construction work at New Vrindaban. They have one son, four years old.

As a child in Morristown, New Jersey, Jack Mowen was more interested in spiritual things than his friends were. He spontaneously gave up eating meat at age seven and began asking probing questions about God that even his Presbyterian minister couldn’t answer to his satisfaction. Later, as a religion major at St. Andrews College in North Carolina, he still couldn’t get satisfying answers to such questions as What is God? Who am I? What is my relationship to Him, and to this world?

As a child in Morristown, New Jersey, Jack Mowen was more interested in spiritual things than his friends were. He spontaneously gave up eating meat at age seven and began asking probing questions about God that even his Presbyterian minister couldn’t answer to his satisfaction. Later, as a religion major at St. Andrews College in North Carolina, he still couldn’t get satisfying answers to such questions as What is God? Who am I? What is my relationship to Him, and to this world?

In 1973, after a spiritual odyssey that took him from one end of the United States to the other, Jack met some Krsna devotees in New York who could answer his questions. He soon joined the Krsna temple there and became Kasyapa dasa. Being a country boy at heart, though, he found the lure of New Vrindaban irresistible and headed for the hills of West Virginia.

Kasyapa (pointing in picture at left) had always had a way with animals, so Srila Bhaktipada put him in charge of New Vrindaban’s most obstreperous team of workhorses. When the massive job of clearing land for the Palace began back in 1974, Kasyapa handled the team that hauled logs and yanked stumps out of the ground. Then it was Kasyapa who headed up the workmen who used dynamite, bulldozers, and trucks to blast, level, and terrace the rough terrain at the Palace site.

“Sometimes, during the big push before the grand opening of the Palace in 1979, I’d be riding the bulldozer eighteen hours a day and longer. It was Srila Bhaktipada’s inspiration—his pure desire to glorify Srila Prabhupada by building something wonderful—that kept me going despite being bone-tired. I could never think of a better way to offer something to Srila Prabhupada for all he’s done for us. Of course, it’s not possible to ever repay him, but I feel very fortunate to have been able to work on Prabhupada’s Palace.”

Leave a Reply