The Biography of a Pure Devotee

“Thousands of young people were walking the streets,

not simply intoxicated or crazy (though they often

were), but searching for life’s ultimate answers.”

by Srila Satsvarupa dasa Goswami

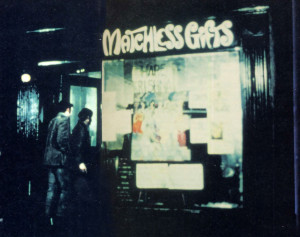

July 1966. America’s first Hare Krsna center, a storefront on Second Avenue, in New York. When Srila Prabhupada chanted the Hare Krsna mantra, young people gathered to hear and take part.

July 1966. America’s first Hare Krsna center, a storefront on Second Avenue, in New York. When Srila Prabhupada chanted the Hare Krsna mantra, young people gathered to hear and take part.

By the summer of Srila Prabhupada’s arrival at 26 Second Avenue, the first front in the great youth rebellion of the sixties had already entered the Lower East Side. Here they were free—free to live in simple poverty and express, find, or lose themselves through art, music, drugs, and sex. The talk was of spiritual searching. LSD and marijuana were the keys, opening new realms of awareness. Notions about Eastern cultures and Eastern religions were in vogue. Through drugs, yoga, brotherhood, or just by being free—somehow they would attain enlightenment. Everyone was supposed to keep an open mind and develop his own cosmic philosophy by direct experience and drug-expanded consciousness blended with his own eclectic readings. And if their lives appeared aimless, at least they had dropped out of a pointless game where the player sells his soul for material goods and so supports a system already rotten. So it was that in 1966, thousands of young people were walking the streets of the Lower East Side, not simply intoxicated or crazy (though they often were), but searching for life’s ultimate answers, in complete disregard of “the establishment” and the day-to-day life pursued by millions of “straight” Americans.

That the prosperous land of America could breed so many discontented youths surprised Srila Prabhupada. Of course, it also further proved that material well-being, the hallmark of American life, couldn’t make people happy. Prabhupada did not see the unhappiness around him in terms of immediate social, political, economic, or cultural causes. Neither slum conditions nor youth rebellions were the all-important realities, but mere symptoms of a universal unhappiness that only Krsna consciousness could cure. He sympathized with these young people’s miseries, but he saw a universal solution.

Prabhupada had not made a study of the youth movement in America before moving to the Lower East Side. He had never even made specific plans to come here amidst so many young people. But in the ten months since Calcutta, he had been moved by force of circumstances, or, as he called it, “by Krsna’s will,” from one place to another. On the order of his spiritual master he had come to America, and by Krsna’s will he had come to the Lower East Side. His mission here was the same as it had been on the Bowery or uptown or even in India. He was fixed in the order of his spiritual master and the Vedic view, a view that wasn’t going to be influenced by the radical changes of the 1960’s. Now if it so happened that these young people, because of some change in the American culture, were to prove more receptive to him, that would be welcome. And that would also be by Krsna’s will.

Actually, because of the ominous influence of the Kali-yuga, the age of quarrel and misfortune foretold in the Vedic scriptures, a degraded age lasting many thousands of years, this was historically the worst of times for spiritual advancement, hippie revolution or not. And he was trying to transplant Vedic culture into a more alien ground than had any previous spiritual master. So he expected to find his life’s mission extremely difficult. Yet in this generally bad age, just prior to Srila Prabhupada’s arrival on the Lower East Side, tremors of dissatisfaction and revolt against the Kali-yuga culture itself began vibrating through American society, sending waves of young people to wander the streets of New York’s Lower East Side in search of something beyond the ordinary life, looking for alternatives, seeking spiritual fulfillment. These young people, broken from their stereotyped materialistic backgrounds and drawn together now on New York’s Lower East Side, were the ones who were by chance or choice or destiny to become the congregation for the Swami’s storefront offerings of kirtana (chanting) and spiritual guidance.

Prabhupada’s arrival went unnoticed. The neighbors said someone new had taken the gift shop next to the laundry. There was a strange picture in the window now, but no one knew what to make of it.

Prabhupada’s arrival went unnoticed. The neighbors said someone new had taken the gift shop next to the laundry. There was a strange picture in the window now, but no one knew what to make of it.

Some passersby noticed a piece of paper taped to the window. A few stopped to read it, but no one knew what to make of it. They didn’t know what Bhagavad-gita was, and the few who did thought, “Maybe a yoga bookstore or something.” The Puerto Ricans in the neighborhood would look in the window at Harvey Cohen’s painting and then blankly walk away. The manager of the Mobil gas station next door couldn’t care less who had moved in; it just didn’t make any difference. The tombstone sellers and undertakers across the street didn’t care. And for the drivers of the countless trucks and cars that passed by, Swamiji’s place didn’t exist at all. But there were young people around who had been intrigued with the painting, who went up to the window to read the little piece of paper. Some of them even knew about the Bhagavad-gita, although the painting of Lord Caitanya and the dancers didn’t seem to fit. A few thought maybe they would attend Swami Bhaktivedanta’s classes and check out the scene.

* * *

Howard Wheeler was hurrying from his apartment on Mott Street to a friend’s apartment on Fifth Street, a quiet place where he hoped to find some peace. He walked up Mott Street to Houston, turned left and began to walk west, across Bowery, past the rushing traffic and stumbling derelicts, and towards Second Avenue.

Howard: “After crossing Bowery, just before Second Avenue, I saw Swamiji jauntily strolling down the sidewalk, his head held high in the air, his hand in the beadbag. He struck me like a famous actor in a very familiar movie. He seemed ageless. He was wearing the traditional saffron-colored robes of a sannyasi and quaint white shoes with points. Coming down Houston, he looked like the genie that popped out of Aladdin’s lamp.”

Howard, age twenty-six, was a tall, large-bodied man with long dark hair, a profuse beard, and black-framed eyeglasses. He was an instructor in English at Ohio State University and was fresh from a trip to India, where he had been looking for a true guru.

Prabhupada noticed Howard, and they both stopped simultaneously. Howard asked the first question that popped into his mind: “Are you from India?”

Prabhupada smiled cordially. “Oh yes, and you?”

Howard: “I told him no, but that I had just returned from India and was very interested in his country and the Hindu philosophy. He told me he had come from Calcutta and had been in New York almost ten months. His eyes were as fresh and cordial as a child’s, and even standing before the trucks that roared and rumbled their way down Houston, he emanated a cool tranquility that was unshakably established in something far beyond the great metropolis that roared around us.”

Howard never made it to his friend’s place that day. He went back to his own apartment on Mott Street, to Keith and Wally, his roommates, to tell them and everyone he knew about the guru who had inexplicably appeared in their midst.

Keith and Howard had been to India. Now they were involved in various spiritual philosophies, and their friends used to come over and talk about enlightenment. Nineteen-year-old Chuck Barnett was a regular visitor.

Chuck: “You would open the door of the apartment, and thousands of cockroaches would disappear into the woodwork. And the smell was enough to knock you over. So Keith was trying to clean the place up and kick some people out. They were sharing the rent—Wally, Keith, Howard, and several others. Due to a lack of any other process, they were using LSD to try and increase their spiritual life. Actually we were all trying to use drugs to help in meditation. Anyway, Wally, Howard, and Keith were trying to find the perfect spiritual master, as we all were.”

Howard remembers his own spiritual seeking as “reading books on Eastern philosophy and religion, burning lots of candles and incense, and taking ganja and peyote and LSD as aids to meditation. Actually, it was more intoxication than meditation. ‘Meditation’ was a euphemism that somehow connected our highs with our readings.”

Keith, twenty-nine, the son of a Southern Baptist minister, was a Ph.D. candidate in history at Columbia University. He was preparing his thesis on “The Rise of Revivalism in the Southern United States.” Dressed in old denim cut-offs, sandals, and a T-shirt, he was something of a guru along the Mott Street coterie.

Wally was in his thirties, shabbily dressed, bearded, intellectual, and well-read in Buddhist literature. He had been a radio engineer in the Army and like his roommates was unemployed. He was reading Alan Watts, Hermann Hesse, and others, talking about spiritual enlightenment, and taking LSD.

In India, Howard and Keith had visited Hardwar, Rishikesh, Benares, and other holy cities, experiencing Indian temples, hashish, and dysentery. One evening in Calcutta they had come upon a group of sadhus chanting the Hare Krsna mantra and playing hand cymbals. For Howard and Keith, as for many Westerners, the essence of Indian philosophy was Sankara’s doctrine of impersonal oneness: all is false except the one impersonal spirit. They had bought books that told them, “Whatever way you express your faith, that way is a valid spiritual path.”

Now the three roommates—Howard, Keith, and Wally—began to mix various philosophies into a hodgepodge of their own. Howard would mix in a little Whitman, Emerson, Thoreau, or Blake, Keith would cite Biblical references, and Wally would add a bit of Buddhist wisdom. And they all kept up on Timothy Leary, Thomas a Kempis, and many others, with the mixture subject to a total reevaluation whenever one of the group experienced a new cosmic insight through LSD.

This was the group that Howard returned to that day in July. Excitedly, he told them about the Swami—how he looked and what he had said. Howard told how after they had stood and talked together the Swami had mentioned his place nearby on Second Avenue, where he was planning to hold some classes. Howard: “I walked around the corner with him. He pointed out a small storefront building between First and Second Streets next door to a Mobil filling station. It had been a curiosity shop, and someone had painted the words MATCHLESS GIFTS over the window. At that time, I didn’t realize how prophetic those words were. ‘This is a good area?’ he asked me. I told him that I thought it was. I had no idea what he was going to offer at his classes, but I knew that all my friends would be glad that an Indian swami was moving into the neighborhood.”

The word spread. Although it wasn’t so easy now for Carl Yeargens and certain others to come up from the Bowery and Chinatown (they had other things to do), Raymond Morris, a twenty-five-year-old writer for comic books, had visited Prabhupada on the Bowery, and when he heard about the Swami’s new place he wanted to drop by. James Greene and Bill Epstein had not forgotten the Swami, and they wanted to come. The Paradox restaurant was still a live connection and brought new interested people. And others, like Stephen Guarino, saw the Swami’s sign in the window. Steve, age twenty-six, was a caseworker for the City’s welfare department, and one day on his lunch break, as he was walking home from the welfare office at Fifth Street and Second Avenue, he saw the Swami’s sign taped to the window. He had been reading a paperback Gita, and he promised himself he would attend the Swami’s class.

Standing with the Swami before the storefront, Howard also had noticed the little sign in the window:

LECTURES IN BHAGAVAD-GITA

A.C. BHAKTIVEDANTA SWAMI

MONDAY, WEDNESDAY, AND FRIDAY

7:00 to 9:00

“Will you bring your friends?” Prabhupada had asked.

“Yes,” Howard had promised. “Monday evening.”

* * *

The summer evening was warm, and in the storefront the back windows and front door were opened wide. Young men, several of them dressed in black denims and button-down sport shirts with broad dull stripes, had left their worn sneakers by the front door and were now sitting on the floor. Most of them were from the Lower East Side; no one had had to go to great trouble to come here. The little room was barren. No pictures, no furniture, no rug, not even a chair. Only a few plain straw mats. A single bulb hung from the ceiling into the center of the room. It was seven o’clock, and about a dozen people had gathered when the Swami suddenly opened the side door and entered the room.

He wasn’t wearing a shirt, and the saffron cloth that draped his torso left his arms and some of his chest bare. His complexion was smooth golden brown, and as they watched him, his head shaven, his ears long-lobed, and his aspect grave, he seemed like pictures they had seen of the Buddha in meditation. He was old, yet erect in his posture, fresh and radiant. His forehead was decorated with the white clay markings of the Vaisnava. Prabhupada recognized big, bearded Howard and smiled. “You have brought your friends?

“Yes.” Howard answered in his loud, resonant voice.

“Ah, very good.”

Prabhupada stepped out of his white shoes, sat down on a thin mat, faced his congregation, and indicated they could all be seated. He distributed several pairs of brass hand cymbals and briefly demonstrated the rhythm: one … two … three. He began playing—a startling, ringing sound. He began singing: Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. Now it was the audience’s turn. “Chant,” he told them. Some already knew, gradually the others caught on, and after a few rounds, all were chanting together.

Most of these young men and the few young women present had at one time or another embarked on the psychedelic voyage in search of a new world of expanded consciousness. Boldly and recklessly, they had entered the turbulent, forbidden waters of LSD, peyote, and magic mushrooms. Heedless of warnings, they had risked everything and done it. Yet there was merit in their valor, their eagerness to find the extra dimensions of the self, to get beyond ordinary existence, even if they didn’t know what the beyond was or whether they would ever return to the comfort of the ordinary. Nonetheless, whatever truth they had found, they remained unfulfilled, and whatever worlds they had reached, these young psychedelic voyagers had always returned to the Lower East Side. Now they were sampling the Hare Krsna mantra.

When the kirtana suddenly sprang from the Swami’s cymbals and sonorous voice, they immediately felt that it was going to be something far out. Here was another chance to “trip out,” and willingly they began to flow with it. They would surrender their minds and explore the limits of the chanting for all it was worth. Most of them had already associated the mantra with the mystical Upanisads and Gita, which had called out to them in words of mystery: “Eternal spirit . . Negating illusion.” But whatever it was, they thought, this Indian mantra—let it come. Let its waves carry us far and high. Let’s take it, and let the effects come. Whatever the price, let it come. The chanting seemed simple and natural enough. It was sweet and wasn’t going to harm anyone. It was, in its own way, far out.

As Srila Prabhupada chanted in his own inner ecstasy, he observed his motley congregation. He was breaking ground in a new land now. As the hand cymbals rang, the lead-and-response of the Hare Krsna mantra swelled, filling the evening. Some neighbors were annoyed. Puerto Rican children, enchanted, appeared at the door and window, looking. Twilight came.

Exotic it was, yet anyone could see that a swami was raising an ancient prayer in praise of God. This wasn’t rock or jazz. He was a holy man, a swami, making a public religious demonstration. But the combination was strange: an old Indian swami chanting an ancient mantra with a storefront full of young American hippies singing along.

Srila Prabhupada sang on, his shaven head high and tilted, his body trembling slightly with emotion. Confidently he led the mantra, absorbed in pure devotion, and they responded. More passersby were drawn to the front window and the open door. Some jeered, but the chanting was too strong. Within the sound of the kirtana, even the car horns were a faint staccato. The vibration of auto engines and the rumble of trucks continued, but in the distance now, unnoticed.

Gathered under the dim electric light in the bare room, the group chanted after their leader, going gradually from a feeble, hesitant chorus to an approximate harmony of voices. They continued clapping and chanting, putting into it whatever they could, in hopes of discovering its secrets—This swami was not simply giving some five-minute sample demonstration. For the moment he was their leader, their guide in an unknown realm—Howard and Keith’s little encounter with a kirtana in Calcutta had left them completely outsiders. The chanting had never before come like this. Right in the middle of the Lower East Side, with a genuine swami leading them.

In their minds were psychedelic ambitions to see the face of God, fantasies and visions of Hindu teachings, and the presumption that IT was all impersonal light. Prabhupada had encountered a similar group on the Bowery, and he knew they weren’t experiencing the mantra with the proper discipline, reverence, and knowledge. But he let them chant in their own way. In time their submission to the spiritual sound, their purification, and their enlightenment and ecstasy in chanting and hearing Hare Krsna would come.

He stopped the kirtana. The chanting had swept back the world, but now the Lower East Side rushed in again. The children at the door began to chatter and laugh. Cars and trucks made their rumblings heard once more. And a voice shouted from a nearby apartment, demanding quiet—It was now past 7:30—Half an hour had elapsed.

Leave a Reply